Equation of State and Phase Transitions in the Nuclear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes: BCS Theory of Superconductivity

Lecture Notes: BCS theory of superconductivity Prof. Rafael M. Fernandes Here we will discuss a new ground state of the interacting electron gas: the superconducting state. In this macroscopic quantum state, the electrons form coherent bound states called Cooper pairs, which dramatically change the macroscopic properties of the system, giving rise to perfect conductivity and perfect diamagnetism. We will mostly focus on conventional superconductors, where the Cooper pairs originate from a small attractive electron-electron interaction mediated by phonons. However, in the so- called unconventional superconductors - a topic of intense research in current solid state physics - the pairing can originate even from purely repulsive interactions. 1 Phenomenology Superconductivity was discovered by Kamerlingh-Onnes in 1911, when he was studying the transport properties of Hg (mercury) at low temperatures. He found that below the liquifying temperature of helium, at around 4:2 K, the resistivity of Hg would suddenly drop to zero. Although at the time there was not a well established model for the low-temperature behavior of transport in metals, the result was quite surprising, as the expectations were that the resistivity would either go to zero or diverge at T = 0, but not vanish at a finite temperature. In a metal the resistivity at low temperatures has a constant contribution from impurity scattering, a T 2 contribution from electron-electron scattering, and a T 5 contribution from phonon scattering. Thus, the vanishing of the resistivity at low temperatures is a clear indication of a new ground state. Another key property of the superconductor was discovered in 1933 by Meissner. -

Phase-Transition Phenomena in Colloidal Systems with Attractive and Repulsive Particle Interactions Agienus Vrij," Marcel H

Faraday Discuss. Chem. SOC.,1990,90, 31-40 Phase-transition Phenomena in Colloidal Systems with Attractive and Repulsive Particle Interactions Agienus Vrij," Marcel H. G. M. Penders, Piet W. ROUW,Cornelis G. de Kruif, Jan K. G. Dhont, Carla Smits and Henk N. W. Lekkerkerker Van't Hof laboratory, University of Utrecht, Padualaan 8, 3584 CH Utrecht, The Netherlands We discuss certain aspects of phase transitions in colloidal systems with attractive or repulsive particle interactions. The colloidal systems studied are dispersions of spherical particles consisting of an amorphous silica core, coated with a variety of stabilizing layers, in organic solvents. The interaction may be varied from (steeply) repulsive to (deeply) attractive, by an appropri- ate choice of the stabilizing coating, the temperature and the solvent. In systems with an attractive interaction potential, a separation into two liquid- like phases which differ in concentration is observed. The location of the spinodal associated with this demining process is measured with pulse- induced critical light scattering. If the interaction potential is repulsive, crystallization is observed. The rate of formation of crystallites as a function of the concentration of the colloidal particles is studied by means of time- resolved light scattering. Colloidal systems exhibit phase transitions which are also known for molecular/ atomic systems. In systems consisting of spherical Brownian particles, liquid-liquid phase separation and crystallization may occur. Also gel and glass transitions are found. Moreover, in systems containing rod-like Brownian particles, nematic, smectic and crystalline phases are observed. A major advantage for the experimental study of phase equilibria and phase-separation kinetics in colloidal systems over molecular systems is the length- and time-scales that are involved. -

Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes from Solid Target Matrices

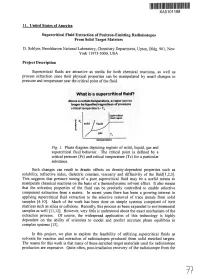

XA0101188 11. United States of America Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes From Solid Target Matrices D. Schlyer, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Chemistry Department, Upton, Bldg. 901, New York 11973-5000, USA Project Description Supercritical fluids are attractive as media for both chemical reactions, as well as process extraction since their physical properties can be manipulated by small changes in pressure and temperature near the critical point of the fluid. What is a supercritical fluid? Above a certain temperature, a vapor can no longer be liquefied regardless of pressure critical temperature - Tc supercritical fluid r«gi on solid a u & temperature Fig. 1. Phase diagram depicting regions of solid, liquid, gas and supercritical fluid behavior. The critical point is defined by a critical pressure (Pc) and critical temperature (Tc) for a particular substance. Such changes can result in drastic effects on density-dependent properties such as solubility, refractive index, dielectric constant, viscosity and diffusivity of the fluid[l,2,3]. This suggests that pressure tuning of a pure supercritical fluid may be a useful means to manipulate chemical reactions on the basis of a thermodynamic solvent effect. It also means that the solvation properties of the fluid can be precisely controlled to enable selective component extraction from a matrix. In recent years there has been a growing interest in applying supercritical fluid extraction to the selective removal of trace metals from solid samples [4-10]. Much of the work has been done on simple systems comprised of inert matrices such as silica or cellulose. Recently, this process as been expanded to environmental samples as well [11,12]. -

Phase Transitions in Quantum Condensed Matter

Diss. ETH No. 15104 Phase Transitions in Quantum Condensed Matter A dissertation submitted to the SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ZURICH¨ (ETH Zuric¨ h) for the degree of Doctor of Natural Science presented by HANS PETER BUCHLER¨ Dipl. Phys. ETH born December 5, 1973 Swiss citizien accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. J. W. Blatter, examiner Prof. Dr. W. Zwerger, co-examiner PD. Dr. V. B. Geshkenbein, co-examiner 2003 Abstract In this thesis, phase transitions in superconducting metals and ultra-cold atomic gases (Bose-Einstein condensates) are studied. Both systems are examples of quantum condensed matter, where quantum effects operate on a macroscopic level. Their main characteristics are the condensation of a macroscopic number of particles into the same quantum state and their ability to sustain a particle current at a constant velocity without any driving force. Pushing these materials to extreme conditions, such as reducing their dimensionality or enhancing the interactions between the particles, thermal and quantum fluctuations start to play a crucial role and entail a rich phase diagram. It is the subject of this thesis to study some of the most intriguing phase transitions in these systems. Reducing the dimensionality of a superconductor one finds that fluctuations and disorder strongly influence the superconducting transition temperature and eventually drive a superconductor to insulator quantum phase transition. In one-dimensional wires, the fluctuations of Cooper pairs appearing below the mean-field critical temperature Tc0 define a finite resistance via the nucleation of thermally activated phase slips, removing the finite temperature phase tran- sition. Superconductivity possibly survives only at zero temperature. -

The Superconductor-Metal Quantum Phase Transition in Ultra-Narrow Wires

The superconductor-metal quantum phase transition in ultra-narrow wires Adissertationpresented by Adrian Giuseppe Del Maestro to The Department of Physics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Physics Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2008 c 2008 - Adrian Giuseppe Del Maestro ! All rights reserved. Thesis advisor Author Subir Sachdev Adrian Giuseppe Del Maestro The superconductor-metal quantum phase transition in ultra- narrow wires Abstract We present a complete description of a zero temperature phasetransitionbetween superconducting and diffusive metallic states in very thin wires due to a Cooper pair breaking mechanism originating from a number of possible sources. These include impurities localized to the surface of the wire, a magnetic field orientated parallel to the wire or, disorder in an unconventional superconductor. The order parameter describing pairing is strongly overdamped by its coupling toaneffectivelyinfinite bath of unpaired electrons imagined to reside in the transverse conduction channels of the wire. The dissipative critical theory thus contains current reducing fluctuations in the guise of both quantum and thermally activated phase slips. A full cross-over phase diagram is computed via an expansion in the inverse number of complex com- ponents of the superconducting order parameter (equal to oneinthephysicalcase). The fluctuation corrections to the electrical and thermal conductivities are deter- mined, and we find that the zero frequency electrical transport has a non-monotonic temperature dependence when moving from the quantum critical to low tempera- ture metallic phase, which may be consistent with recent experimental results on ultra-narrow MoGe wires. Near criticality, the ratio of the thermal to electrical con- ductivity displays a linear temperature dependence and thustheWiedemann-Franz law is obeyed. -

Density Fluctuations Across the Superfluid-Supersolid Phase Transition in a Dipolar Quantum Gas

PHYSICAL REVIEW X 11, 011037 (2021) Density Fluctuations across the Superfluid-Supersolid Phase Transition in a Dipolar Quantum Gas J. Hertkorn ,1,* J.-N. Schmidt,1,* F. Böttcher ,1 M. Guo,1 M. Schmidt,1 K. S. H. Ng,1 S. D. Graham,1 † H. P. Büchler,2 T. Langen ,1 M. Zwierlein,3 and T. Pfau1, 15. Physikalisches Institut and Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology, Universität Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 57, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany 2Institute for Theoretical Physics III and Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology, Universität Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 57, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany 3MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms, Research Laboratory of Electronics, and Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA (Received 15 October 2020; accepted 8 January 2021; published 23 February 2021) Phase transitions share the universal feature of enhanced fluctuations near the transition point. Here, we show that density fluctuations reveal how a Bose-Einstein condensate of dipolar atoms spontaneously breaks its translation symmetry and enters the supersolid state of matter—a phase that combines superfluidity with crystalline order. We report on the first direct in situ measurement of density fluctuations across the superfluid-supersolid phase transition. This measurement allows us to introduce a general and straightforward way to extract the static structure factor, estimate the spectrum of elementary excitations, and image the dominant fluctuation patterns. We observe a strong response in the static structure factor and infer a distinct roton minimum in the dispersion relation. Furthermore, we show that the characteristic fluctuations correspond to elementary excitations such as the roton modes, which are theoretically predicted to be dominant at the quantum critical point, and that the supersolid state supports both superfluid as well as crystal phonons. -

Lecture 5 Non-Aqueous Phase Liquid (NAPL) Fate and Transport

Lecture 5 Non-Aqueous Phase Liquid (NAPL) Fate and Transport Factors affecting NAPL movement Fluid properties: Porous medium: 9 Density Permeability 9 Interfacial tension Pore size 9 Residual saturation Structure Partitioning properties Solubility Ground water: Volatility and vapor density Water content 9 Velocity Partitioning processes NAPL can partition between four phases: NAPL Gas Solid (vapor) Aqueous solution Water to gas partitioning (volatilization) Aqueous ↔ gaseous Henry’s Law (for dilute solutions) 3 Dimensionless (CG, CW in moles/m ) C G = H′ CW Dimensional (P = partial pressure in atm) P = H CW Henry’s Law Constant H has dimensions: atm m3 / mol H’ is dimensionless H’ = H/RT R = gas constant = 8.20575 x 10-5 atm m3/mol °K T = temperature in °K NAPL to gas partitioning (volatilization) NAPL ↔ gaseous Raoult’s Law: CG = Xt (P°/RT) Xt = mole fraction of compound in NAPL [-] P° = pure compound vapor pressure [atm] R = universal gas constant [m3-atm/mole/°K] T = temperature [°K] Volatility Vapor pressure P° is measure of volatility P° > 1.3 x 10-3 atm → compound is “volatile” 1.3 x 10-3 > P° > 1.3 x 10-13 atm → compound is “semi-volatile” Example: equilibrium with benzene P° = 76 mm Hg at 20°C = 0.1 atm R = 8.205 x 10-5 m3-atm/mol/°K T = 20°C (assumed) = 293°K Assume 100% benzene, mole fraction Xt = 1 3 CG = Xt P°/(RT) = 4.16 mol/m Molecular weight of benzene, C6H6 = 78 g/mol 3 3 CG = 4.16 mol/m × 78 g/mol = 324 g/m = 0.32 g/L 6 CG = 0.32 g/L x 24 L/mol / (78 g/mol) x 10 = 99,000 ppmv One mole of ideal gas = 22.4 L at STP (1 atm, 0 C), Corrected to 20 C: 293/273*22.4 = 24.0 L/mol Gas concentration in equilibrium with pure benzene NAPL Example: equilibrium with gasoline Gasoline is complex mixture – mole fraction is difficult to determine and varies Benzene = 1 to several percent (Cline et al., 1991) Based on analysis reported by Johnson et al. -

Introduction to Unconventional Superconductivity Manfred Sigrist

Introduction to Unconventional Superconductivity Manfred Sigrist Theoretische Physik, ETH-Hönggerberg, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland Abstract. This lecture gives a basic introduction into some aspects of the unconventionalsupercon- ductivity. First we analyze the conditions to realized unconventional superconductivity in strongly correlated electron systems. Then an introduction of the generalized BCS theory is given and sev- eral key properties of unconventional pairing states are discussed. The phenomenological treatment based on the Ginzburg-Landau formulations provides a view on unconventional superconductivity based on the conceptof symmetry breaking.Finally some aspects of two examples will be discussed: high-temperature superconductivity and spin-triplet superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. Keywords: Unconventional superconductivity, high-temperature superconductivity, Sr2RuO4 INTRODUCTION Superconductivity remains to be one of the most fascinating and intriguing phases of matter even nearly hundred years after its first observation. Owing to the breakthrough in 1957 by Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer we understand superconductivity as a conden- sate of electron pairs, so-called Cooper pairs, which form due to an attractive interaction among electrons. In the superconducting materials known until the mid-seventies this interaction is mediated by electron-phonon coupling which gises rise to Cooper pairs in the most symmetric form, i.e. vanishing relative orbital angular momentum and spin sin- glet configuration (nowadays called s-wave pairing). After the introduction of the BCS concept, also studies of alternative pairing forms started. Early on Anderson and Morel [1] as well as Balian and Werthamer [2] investigated superconducting phases which later would be identified as the A- and the B-phase of superfluid 3He [3]. In contrast to the s-wave superconductors the A- and B-phase are characterized by Cooper pairs with an- gular momentum 1 and spin-triplet configuration. -

Phase Diagrams a Phase Diagram Is Used to Show the Relationship Between Temperature, Pressure and State of Matter

Phase Diagrams A phase diagram is used to show the relationship between temperature, pressure and state of matter. Before moving ahead, let us review some vocabulary and particle diagrams. States of Matter Solid: rigid, has definite volume and definite shape Liquid: flows, has definite volume, but takes the shape of the container Gas: flows, no definite volume or shape, shape and volume are determined by container Plasma: atoms are separated into nuclei (neutrons and protons) and electrons, no definite volume or shape Changes of States of Matter Freezing start as a liquid, end as a solid, slowing particle motion, forming more intermolecular bonds Melting start as a solid, end as a liquid, increasing particle motion, break some intermolecular bonds Condensation start as a gas, end as a liquid, decreasing particle motion, form intermolecular bonds Evaporation/Boiling/Vaporization start as a liquid, end as a gas, increasing particle motion, break intermolecular bonds Sublimation Starts as a solid, ends as a gas, increases particle speed, breaks intermolecular bonds Deposition Starts as a gas, ends as a solid, decreases particle speed, forms intermolecular bonds http://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulation/states- of-matter The flat sections on the graph are the points where a phase change is occurring. Both states of matter are present at the same time. In the flat sections, heat is being removed by the formation of intermolecular bonds. The flat points are phase changes. The heat added to the system are being used to break intermolecular bonds. PHASE DIAGRAMS Phase diagrams are used to show when a specific substance will change its state of matter (alignment of particles and distance between particles). -

States of Matter

States of Matter A Museum of Science Traveling Program Description States of Matter is a 60- minute presentation about the characteristics of solids, liquids, gases, and the temperature- dependent transitions between them. It is designed to build on NGSS-based curricula. NGSS: Next Generation Science Standards Needs We bring all materials and equipment, including a video projector and screen. Access to 110- volt electricity is required. Space Requirements The program can be presented in assembly- suitable spaces like gyms, multipurpose rooms, cafeterias, and auditoriums. Goals: Changing State A major goal is to show that all substances will go through phase changes and that every substance has its own temperatures at which it changes state. Goals: Boiling Liquid nitrogen boils when exposed to room temperature. When used with every day objects, it can lead to unexpected results! Goals: Condensing Placing balloons in liquid nitrogen causes the gas inside to condense, shrinking the balloons before the eyes of the audience! Latex-free balloons are available for schools with allergic students. Goals: Freezing Nitrogen can also be used to flash-freeze a variety of liquids. Students are encouraged to predict the results, and may end up surprised! Goals: Behavior Changes When solids encounter liquid nitrogen, they can no longer change state, but their properties may have drastic—sometimes even shattering— changes. Finale Likewise, the properties of gas can change at extreme temperatures. At the end of the program, a blast of steam is superheated… Finale …incinerating a piece of paper! Additional Content In addition to these core goals, other concepts are taught with a variety of additional demonstrations. -

Superconducting Phase Transition in Inhomogeneous Chains of Superconducting Islands

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Faculty Publications 2020 Superconducting Phase Transition in Inhomogeneous Chains of Superconducting Islands Eduard Ilin Irina Burkova Xiangyu Song Michael Pak Air Force Institute of Technology Dmitri S. Golubev See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/facpub Part of the Condensed Matter Physics Commons, and the Electromagnetics and Photonics Commons Recommended Citation Ilin, E., Burkova, I., Song, X., Pak, M., Golubev, D. S., & Bezryadin, A. (2020). Superconducting phase transition in inhomogeneous chains of superconducting islands. Physical Review B, 102(13), 134502. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.102.134502 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Eduard Ilin, Irina Burkova, Xiangyu Song, Michael Pak, Dmitri S. Golubev, and Alexey Bezryadin This article is available at AFIT Scholar: https://scholar.afit.edu/facpub/671 PHYSICAL REVIEW B 102, 134502 (2020) Superconducting phase transition in inhomogeneous chains of superconducting islands Eduard Ilin ,1 Irina Burkova ,1 Xiangyu Song ,1 Michael Pak ,2 Dmitri S. Golubev ,3 and Alexey Bezryadin 1 1Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA 2Department of Physics, Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright-Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio 45433, USA 3Pico group, QTF Centre of Excellence, Department of Applied Physics, Aalto University, FI-00076 Aalto, Finland (Received 7 August 2020; revised 11 September 2020; accepted 11 September 2020; published 2 October 2020) We study one-dimensional chains of superconducting islands with a particular emphasis on the regime in which every second island is switched into its normal state, thus forming a superconductor-insulator-normal metal (S-I-N) repetition pattern. -

Superconductivity in Pictures

Superconductivity in pictures Alexey Bezryadin Department of Physics University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Superconductivity observation Electrical resistance of some metals drops to zero below a certain temperature which is called "critical temperature“ (H. K. O. 1911) How to observe superconductivity Heike Kamerling Onnes - Take Nb wire - Connect to a voltmeter and a current source - Put into helium Dewar - Measure electrical resistance R (Ohm) A Rs V Nb wire T (K) 10 300 Dewar with liquid Helium (4.2K) Meissner effect – the key signature of superconductivity Magnetic levitation Magnetic levitation train Fundamental property of superconductors: Little-Parks effect (’62) The basic idea: magnetic field induces non-zero vector-potential, which produces non- zero superfluid velocity, thus reducing the Tc. Proves physical reality of the vector- potential Discovery of the proximity Non-superconductor (normal metal, i.e., Ag) effect: A supercurrent can flow through a thin layers of a non- superconducting metals “sandwitched” between two superconducting metals. tin Superconductor (tin) Explanation of the supercurrent in SNS junctions --- Andreev reflection tin A.F. Andreev, 1964 Superconducting vortices carry magnetic field into the superconductor (type-II superconductivity) Amazing fact: unlike real tornadoes, superconducting vortices (also called Abrikosov vortices) are all exactly the same and carry one quantum of the Magnetic flux, h/(2e). By the way, the factor “2e”, not just “e”, proves that superconducting electrons move in pairs.