A Help-Sheet for Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LIVING CHURCH Is Published by the Living Church Foundation

Income from Church Property TLC Partners Theology of the Prayer Book February 12, 2017 THE LIV ING CHURCH CATHOLIC EVANGELICAL ECUMENICAL Prayer & Protest $5.50 livingchurch.org Architecture THE LIVING ON THE COVER HURCH Presiding Bishop Michael Curry: “I C pray for the President in part because THIS ISSUE February 12, 2017 Jesus Christ is my Savior and Lord. If | Jesus is my Lord and the model and guide for my life, his way must be my NEWS way, however difficult” (see “Prayer, 4 Prayer, Protest Greet President Trump Protest Greet President Trump,” p. 4). 6 Objections to Consecration in Toronto Danielle E. Thomas photo 10 Joanna Penberthy Consecrated 6 FEATURES 13 Property Potential: More Churches Consider Property Redevelopment to Survive and Thrive By G. Jeffrey MacDonald 16 NECESSARy OR ExPEDIENT ? The Book of Common Prayer (2016) | By Kevin J. Moroney BOOKS 18 The Nicene Creed: Illustrated and Instructed for Kids Review by Caleb Congrove ANNUAL HONORS 13 19 2016 Living Church Donors OTHER DEPARTMENTS 24 Cæli enarrant 26 Sunday’s Readings LIVING CHURCH Partners We are grateful to Church of the Incarnation, Dallas [p. 27], and St. John’s Church, Savannah [p. 28], whose generous support helped make this issue possible. THE LIVING CHURCH is published by the Living Church Foundation. Our historic mission in the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion is to seek and serve the Catholic and evangelical faith of the one Church, to the end of visible Christian unity throughout the world. news | February 12, 2017 Prayer, Protest Greet President Trump The Jan. 20 inauguration of Donald diversity of views, some of which have Trump as the 45th president of the been born in deep pain,” he said. -

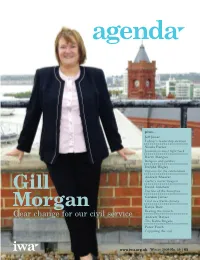

Gill Morgan, Is Dealing with Whitehall Arrogance

plus… Jeff Jones Labour’s leadership election Nicola Porter Journalism must fight back Barry Morgan Religion and politics Dafydd Wigley Options for the referendum Andrew Shearer Garlic’s secret weapon Gill David Culshaw Decline of the honeybee Gordon James Coal in a warm climate Morgan Katija Dew Beating the crunch Gear change for our civil service Andrew Davies The Kafka Brigade Peter Finch Capturing the soul www.iwa.org.uk Winter 2009 No. 39 | £5 clickonwales ! Coming soon, our new website www. iwa.or g.u k, containing much more up-to-date news and information and with a freshly designed new look. Featuring clickonwales – the IWA’s new online service providing news and analysis about current affairs as it affects our small country. Expert contributors from across the political spectrum will be commissioned daily to provide insights into the unfolding drama of the new 21 st Century Wales – whether it be Labour’s leadership election, constitutional change, the climate change debate, arguments about education, or the ongoing problems, successes and shortcomings of the Welsh economy. There will be more scope, too, for interactive debate, and a special section for IWA members. Plus: Information about the IWA’s branches, events, and publications. This will be the must see and must use Welsh website. clickonwales and see where it takes you. clickonwales and see how far you go. The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges core funding from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust , the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation . The following organisations are corporate members: Private Sector • Principality Building Society • The Electoral Commission Certified Accountants • Abaca Ltd • Royal Hotel Cardiff • Embassy of Ireland • Autism Cymru • Beaufort Research • Royal Mail Group Wales • Fforwm • Cartrefi Cymunedol / • Biffa Waste Services Ltd • RWE NPower Renewables • The Forestry Commission Community Housing Cymru • British Gas • S. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

R.S. Thomas: Poetic Horizons

R.S. Thomas: Poetic Horizons Karolina Alicja Trapp Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 The School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis engages with the poetry of R.S. Thomas. Surprisingly enough, although acclaim for Thomas as a major figure on the twentieth century’s literary scene has been growing perceptibly, academic scholarship has not as yet produced a full-scale study devoted specifically to the poetic character of Thomas’s writings. This thesis aims to fill that gap. Instead of mining the poetry for psychological, social, or political insights into Thomas himself, I take the verse itself as the main object of investigation. My concern is with the poetic text as an artefact. The main assumption here is that a literary work conveys its meaning not only via particular words and sentences, governed by the grammar of a given language, but also through additional artistic patterning. Creating a new set of multi-sided relations within the text, this “supercode” leads to semantic enrichment. Accordingly, my goal is to scrutinize a given poem’s artistic organization by analysing its component elements as they come together and function in a whole text. Interpretations of particular poems form the basis for conclusions about Thomas’s poetics more generally. Strategies governing his poetic expression are explored in relation to four types of experience which are prominent in his verse: the experience of faith, of the natural world, of another human being, and of art. -

Diocesan-Cycle-Of-Pr

Diocese of Chelmsford NOTES: Where parochial links are known to exist the names of overseas workers are placed immediately after the appropriate parish. Further information concerning overseas Cycle of Prayer dioceses, including the names of bishops, is contained in the Anglican Cycle of Prayer, for daily use in available on their website http://www.anglicancommunion.org/acp/main.cfm To contact the Diocese of Chelmsford about the Cycle of Prayer in The Month or online, February and March 2017 Now on Twitter @chelmsdio please email internal/[email protected] ABBREVIATIONS: Prayer is the sum of our relationship with God. We are what we pray. (Carlo Carretto) A Assistant Clergy; AAD Assistant Area Dean; AC Associate Priest/Minister; AD Area Dean; AM Assistant Minister, AR Associate Rector; AV Associate Vicar; AYO Area Youth Officer, Brigid, Abbess of Kildare, c.525 Wed 1 BMO Bishop’s Mission Order; BP Bishop; CA Church Army; CIC Curate in Charge; CHP The Deanery of Epping Forest & Ongar continued… Chaplain; EVN Evangelist; HT Head Teacher; LLM Licensed Lay Minister; MCD Minister of Fyfield (St Nicholas), Moreton (St Mary Vn) w Bobbingworth Conventional District; MIC Minister in Charge; PEV Provincial Episcopal Visitor; PIC Priest in (St Germain) & Willingale (St Christopher) w Shellow and Berners Charge; PP Public Preacher; R Rector; RD Rural Dean; Rdes Rector designate; RDR Reader; PTO Permission to Officiate; RES Residentiary Canon; Sr Sister, TM Team Ministry; TR Roding Team Rector; TV Team Vicar; V Vicar; Vdes Vicar designate; WDN Warden. Clergy: Christine Hawkins (PIC), Sam Brazier‐Gibbs (OPM). Reader: Pam Watson Hon. -

Lambeth I.10 and All That

Vol 3 Issue 4.qxp 07/12/2005 09:39 Page 11 Lambeth I.10 and all that ARCHBISHOP BARRY MORGAN The Archbishop of the Anglican Church in Wales explores some of the underlying principles in the current debates on sexuality. here can be little doubt that the topics during the conference. The 1998 Lambeth Resolution on headings were: Called to Full Humanity; T Human Sexuality – Lambeth Called to Live and Proclaim the Good I.10 as it has come to be known – has News; Called to be a Faithful Church in a had a profound effect on the Anglican Plural World; and Called to be One. In Communion. In fact you could be other words the four main topics dealt pardoned for wondering whether the with were human affairs, mission, Anglican Communion has, since then, interfaith, and unity issues. Human been interested in any other topic, sexuality was one subject area, within because it has dominated the agendas the human affairs topic, which also of Provinces, meetings of Primates and examined themes such as human of the Anglican Consultative Council. rights, human dignity, the The ordination of a practising environment, questions about modern homosexual as a Bishop in the USA technology, euthanasia, international and the blessing of same sex debt and economic justice. Sexuality relationships in Canada might not then was one topic among many others, have had the repercussions they have but I suspect that by now no one had, if the Lambeth Conference in remembers that. I.10 seems to be the 1998 had not had such an acrimonious only resolution that counts. -

Campusthe Magazine for University of Wales Alumni

Summer 20178 www.wales.ac.uk/alumni CampusThe Magazine for University of Wales Alumni nn Ensuring a legacy for future generations nn A delegation from the Arctic visits the Dictionary nn 2017 Graduation Celebration nn Graduate awarded prestigious environmental prize nn The transformed institution - looking to the future nn Introducing the new Director of the University of Wales Press nn Graduates part of Oscar winning team Welcome from your Alumni Officer As we proceed towards merger with Welcome the University of Wales Trinity Saint David (UWTSD), the University is keen from the Vice-Chancellor to ensure that graduates feel informed about the process, and have the t was in October of 2011 opportunity to share any comments. that the University of It is important to stress that these IWales and the University current changes within the University of Wales Trinity Saint David should not affect graduates in any way. (UWTSD) first announced that Graduates will still retain the University of Wales award that they received they had made the significant upon graduation and will continue to and historic decision to seek be valued members of the University of irrevocable constitutional Wales Alumni Association. change. The transformed University will Transformation, adaptability and flexibility celebrate and embrace the thousands are familiar words to organisations working of graduates around the world who in these challenging times, and these are hold a Wales degree, and it will ensure words that also define the journey that has that they receive the same services led us to this point in the integration. A complex process, both institutions have and support that they receive now. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 JANUARY 4/1 Church of England: Diocese of Chichester, Bishop Martin Warner, Bishop Mark Sowerby, Bishop Richard Jackson Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Mikkeli, Bishop Seppo Häkkinen 11/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Richard Chartres, Bishop Adrian Newman, Bishop Peter Wheatley, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Paul Williams, Bishop Jonathan Baker Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Helga Haugland Byfuglien, Bishop Tor Singsaas 18/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Samuel Salmi Church of Norway: Diocese of Soer-Hålogaland (Bodoe), Bishop Tor Berger Joergensen Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Chris Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. 25/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Tampere, Bishop Matti Repo Church of England: Diocese of Manchester, Bishop David Walker, Bishop Chris Edmondson, Bishop Mark Davies Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 FEBRUARY 1/2 Church of England: Diocese of Birmingham, Bishop David Urquhart, Bishop Andrew Watson Church of Ireland: Diocese of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, Bishop Paul Colton Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark: Diocese of Elsinore, Bishop Lise-Lotte Rebel 8/2 Church in Wales: Diocese of Bangor, Bishop Andrew John Church of Ireland: Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough, Archbishop Michael Jackson 15/2 Church of England: Diocese of Worcester, Bishop John Inge, Bishop Graham Usher Church of Norway: Diocese of Hamar, Bishop Solveig Fiske 22/2 Church of Ireland: Diocese -

PD March 2012.Indd

www.stdavidsdiocese.org.uk www.facebook.com/pobl.dewi http://twitter.com./PoblDewi Mawrth/March 2012 Dealing with differences Governing Body to vote on the Anglican Covenant OMETIMES single events can bring to a crisis tensions the Episcopal Church in the USA which have been simmering for a long time. (TEC) said effectively that they For the Anglican Church worldwide that event were not bound by the advice of S the Bishops of the Communion. happened on 5th August 2003 when the General Convention The Archbishop of Canterbury of the Episcopal Church of the USA gave formal consent to the warned that Robinson’s election election of Gene Robinson as Bishop of New Hampshire. ‘will inevitably have a significant The reason this sent shock waves around the world was that Gene impact on the Anglican Commun- Robinson was a previously-married and now-divorced man, who since ion throughout the world’. But 1988 had been cohabiting with his male partner (they entered a civil TEC did not feel bound to notice union with one another in 2008). Rowan Williams’ warning, either. So, what do TEC feel bound Bishop Robinson’s election The debate started in 1998 by? What is any Anglican bound prompted a decade of delibera- when the worldwide gathering by? These were the long-simmering tion which resulted in a document of Bishops from the Anglican questions which Gene Robinson’s known as the Anglican Covenant. Communion (the Lambeth Confer- election brought into focus. In April this year the Govern- ence) discussed human sexuality No-one ever planned a world- © ACNS ing Body of the Church in Wales is and passed, with strong support, a wide Anglican Communion. -

Faithful Abundance the Church's One Foundation

Build New Churches t JANUARY 2009 t VOLUME 118 t NUMBER 1 Faithful Abundance Ten approaches to faithful stewardship in unsettling times By Patricia Bjorling It would be an understatement practical responses. We must move staff and your church’s members are to say we are living in unsettling stewardship to the center of our all praying for abundant funding Itimes. There is probably not a lives together as Christians, and we for the work of the church, they will single segment of society—from must make sure we are constantly open hearts, uncover new resources Enhance Conference Centers Enhance Conference individuals to institutions—that is educating about stewardship and and reveal unexpected possibilities. not experiencing a measure of fear using best practices in how we t and anxiety about the financial carry out the “mechanics” of annual 2 t Teach abundance. The media future. As Christians, our response stewardship efforts. bombards us daily with stories of must focus both on the spiritual Here are 10 basics for / Stewardship continued on page 6 and the practical. The Rev. Kirk approaching stewardship during a Kubicek, rector of St. Paul’s, Ellicott time such as this. City, Md., makes a good case for a spiritual response: “The current 1 t Pray intentionally crisis is a spiritual crisis of amnesia, for generous hearts. So of forgetting who we are and whose frequently we approach we are.” Giving and stewardship the vital undertaking are a faith response, and giving and of raising funds for Expand Youth Ministries Expand Youth stewardship can suffer when our ministry without asking t trust in God wavers. -

Diamond Wedding Anniversary

The Abbey is served by a hearing loop. Users should turn their hearing aid to the setting marked T. Please ensure that mobile telephones and pagers are switched OFF. The Service is conducted by The Very Reverend Dr John Hall, Dean of Westminster. The Cross of Westminster, Processional Candles, and Banners are borne by the Brotherhood of St Edward the Confessor, all of whose members are former Choristers of the Abbey. Five of the members of the Brotherhood at this Service were Choristers in 1947 and sang at the Wedding of Her Royal Highness The Princess Elizabeth and His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh. The Service is sung by the Choir of Westminster Abbey, conducted by James O’Donnell, Organist and Master of the Choristers. The organ is played by Robert Quinney, Sub-Organist. The fanfares are played by the State Trumpeters of the Band of The Blues and Royals, led by Trumpet Major G S Sewell-Jones, and by the Fanfare Trumpeters of the Band of the Scots Guards, directed by Lieutenant Colonel R J Owen. 1 Music before the Service: Ashley Grote, Assistant Organist, plays: Sonata No 2 Op 87a in B flat ‘The Severn Suite’ Edward Elgar (1857-1934) i. Introduction arranged by Ivor Atkins (1869-1953) ii. Toccata iii. Fugue iv. Cadenza – Coda Sonata V BWV 529 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Allegro – Largo – Allegro Crown Imperial William Walton (1902-83) Fantasy on St Columba Kenneth Leighton (1929-88) ‘The King of Love my Shepherd is’ Jesus bleibet meine Freude Johann Sebastian Bach from Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben BWV 147 Bridal March Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848-1918) from The Birds of Aristophanes arranged by Walter Alcock (1861-1947) 2 The Procession of Representatives of Faith Communities moves to the North Lantern. -

Llandaff Welcomes Bishop June

Diocese of LLANDAFF YR EGLWYS YNG NGHYMRU | THE CHURCH IN WALES Summer 2017 Llandaff welcomes Bishop June Inside From transplant to 10k Meet our trainee priests NEWS A message to the diocese: Bishop June’s letter issued following her appointment in April “The announcement Bishops, which was that I am to become agreed by the Bishops the 72nd Bishop of following the Canon Llandaff was a very which enabled the special moment for ordination of women me personally, for the as Bishops, also diocesan family and recognises that we are for those in Salisbury fully and unequivocally who will be saying committed to this farewell to me. I have kind of appointment. no doubt that this is My hope is that God’s call to me and I every member of the am profoundly grateful diocesan community that the privilege to will feel valued and serve in this wonderful encouraged because ecclesial community the quality of our will be mine. Thank you life together and to all who have already the strength of our made me feel so welcomed or who have Cathedral. It is my hope that we will be relatedness is hugely important to me. sent me good wishes and the promise of able to invite as wide a representation A fresh start in ministry is always their prayers. as possible from the diocese to both of a new adventure. I’m very aware that You may already know that Paul and I these services. I don’t yet know what I don’t know! I have lots of family in the diocese and he I’m aware that my appointment will will be looking to my colleagues across was born not that far from Llys Esgob so be the cause of nervousness for some all the parishes to discern with me the there is for us a great sense of returning who find themselves unable to accept workings of God’s Spirit and to rejoice to roots in this move.