Aberystwyth University “For Those Who Do Not Know”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carn 147 August 2010

Carn No 147 August 2010:Issue No 138 October 2007.qxd 20/08/2010 11:11 Page 1 No. 147 Autumn 2010 €4.00 Stg£3.00 Ÿ British Policy: Contempt for Scotland and Wales Ÿ Dihun Conference: Towards an Early Trilingualism Ÿ Pressure to Grant Welsh Language Rights Ÿ Gwobrau ‘caru’r Gymraeg’ i fusnesau - menter gan y Gymdeithas Ÿ Restore Ireland’s Neutrality Ÿ One and All – a Cornish Voice Ÿ Mannin – Nationalist Awakening Ÿ Celtic League AGM 2010 Ÿ Alexi Kondratiev R.I.P., Tributes ALBA: AN COMANN CEILTEACH BREIZH: AR C’HEVRE KELTIEK CYMRU: YR UNDEB CELTAIDD ÉIRE: AN CONRADH CEILTEACH KERNOW: AN KESUNYANS KELTEK MANNIN: YN COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Carn No 147 August 2010:Issue No 138 October 2007.qxd 20/08/2010 11:11 Page 2 Alba Seumas MacGaraidh: Neach-iomairt Ghàidhlig agus Fior ‘Pan Celt’ Chaidh James Carr Hay a bhreith ann an Breatannach agus Innseanach cuairtichte leis Obair-Bhrothaig ann an 1885.On a bha e na na Tuirceach ann an Kut-al-Amara. Dh’ dhuine òg, thug e an t-ainm Seumas fhuirich MacGaraidh anns an Ear-Mheadhan MacGaraidh. Thathar a radh gun robh na h- airson ceithir bliadhna. Albannaich anns an fhairsaingeachd prìseil air na chuir iad ri buaidh na Ìompaireachd Celtic Congress Bhreatannach, ’s le sin, ’s e adhbhar- Ann an 1920 sgrìobh MacGaraidh artagail iongnaidh gun do dh’ fhàs MacGaraidh a airson an Arbroath Herald, a’ toirt bhith, mar a chuir a charaid Seumas Mac a’ eachdraidh air na cruinneachan aig toisheach Ghobhainn an ainm air, ‘a one-man an fhiceadamh linn. -

Meic Stephens Manuscripts, (GB 0210 MSMEICST)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Meic Stephens Manuscripts, (GB 0210 MSMEICST) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 08, 2017 Printed: May 08, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/meic-stephens-manuscripts archives.library .wales/index.php/meic-stephens-manuscripts Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Meic Stephens Manuscripts, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau -

Brismes Annual Conference 2016 Networks Connecting the Middle East Through Time, Space and Cyberspace

BRISMES ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2016 NETWORKS CONNECTING THE MIDDLE EAST THROUGH TIME, SPACE AND CYBERSPACE www.brismes.ac.uk/conference 13 – 15 July 2016 University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter Campus 13 – 15 July, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter Campus 1 New titles from I.B.Tauris www.ibtauris.com WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS Welcome from BRISMES It is a great pleasure to welcome you to this year’s Annual Conference of the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies (BRISMES). This is the first time that BRISMES has convened its Annual Conference in Wales, and we are delighted to hold it in collaboration with the University of Wales Trinity Saint David at their Lampeter Campus. I would like to thank our Conference Convenor, Gary Bunt, Reader in Islamic Studies here in Lampeter for making this possible and allowing so many of us to come and enjoy this beautiful setting. This year’s theme has encouraged a diverse mix of papers. With presentations exploring political mobilisation networks, religious networks, cultural networks, smuggling networks, trade networks, social networks online, and those connecting the Middle East through time and space, there is a fascinatingly diverse range of panels to attend. We are delighted that the keynote address will be given by the Welsh author, poet and lyricist Grahame Davies, and that he will celebrate this conference’s particular setting by exploring the centuries-long historical connection between Wales and Islam. As a former Ambassador to Yemen I am familiar with the long trading connections between Yemen and Cardiff and am looking forward to learning more about the even deeper historical links with Islam. -

Facebook: Facebook.Com/Serenbooks Twitter: @Serenbooks

C o Distribution Wales Distribution & representation v e r england, scotland, ireland, europe Welsh books Council i m Central books ltd, 99 Wallis road uned 16, stad Glanyrafon, llanbadarn, a g e : london, e9 5ln aberystwyth sY23 3aQ s t i l phone 0845 458 9911 Fax 0845 458 9912 phone 01970 624455 Fax 01970 625506 l f r [email protected] [email protected] o m sales and Marketing Manager: tom Ferris T h representation e [email protected] G inpress ltd o s p Churchill house, 12 Mosley street, e l o newcastle upon tyne, ne1 1De north aMeriCa Distribution & f U s www.inpressbooks.co.uk representation d i r . phone 0191 230 8104 independent publishers Group D a Managing Director: rachael ogden 814 north Franklin street v e [email protected] Chicago il60610 M c K sales and Marketing : James hogg phone (312) 337 0747 Fax (312) 337 5985 e a [email protected] [email protected] n seren, 57 nolton street, bridgend, CF31 3ae 01656 663018 [email protected] www.serenbooks.com Facebook: facebook.com/serenbooks twitter: @serenbooks publisher: Mick Felton sales and Marketing: simon hicks Marketing: Victoria humphreys Fiction editor: penny thomas poetry editor: amy Wack poetry Wales: robin Grossmann, rebecca parfitt Directors: Cary archard (Founder and patron), John barnie, Duncan Campbell, robert edge, richard houdmont (Chair), patrick McGuinness, linda osborn (secretary), sioned puw rowlands, Christopher Ward no. 2262728. Vat no. Gb484323148. seren is the imprint of poetry Wales press ltd, which works with the financial assistance of the Welsh books Council www.serenbooks.com Preface 3 2011 was an exciting year in which we celebrated our 30th birthday and threw a street Cynan Jones Bird, Blood, Snow 4 party outside the seren offices on the sunniest october saturday since records began. -

THE LIVING CHURCH Is Published by the Living Church Foundation

Income from Church Property TLC Partners Theology of the Prayer Book February 12, 2017 THE LIV ING CHURCH CATHOLIC EVANGELICAL ECUMENICAL Prayer & Protest $5.50 livingchurch.org Architecture THE LIVING ON THE COVER HURCH Presiding Bishop Michael Curry: “I C pray for the President in part because THIS ISSUE February 12, 2017 Jesus Christ is my Savior and Lord. If | Jesus is my Lord and the model and guide for my life, his way must be my NEWS way, however difficult” (see “Prayer, 4 Prayer, Protest Greet President Trump Protest Greet President Trump,” p. 4). 6 Objections to Consecration in Toronto Danielle E. Thomas photo 10 Joanna Penberthy Consecrated 6 FEATURES 13 Property Potential: More Churches Consider Property Redevelopment to Survive and Thrive By G. Jeffrey MacDonald 16 NECESSARy OR ExPEDIENT ? The Book of Common Prayer (2016) | By Kevin J. Moroney BOOKS 18 The Nicene Creed: Illustrated and Instructed for Kids Review by Caleb Congrove ANNUAL HONORS 13 19 2016 Living Church Donors OTHER DEPARTMENTS 24 Cæli enarrant 26 Sunday’s Readings LIVING CHURCH Partners We are grateful to Church of the Incarnation, Dallas [p. 27], and St. John’s Church, Savannah [p. 28], whose generous support helped make this issue possible. THE LIVING CHURCH is published by the Living Church Foundation. Our historic mission in the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion is to seek and serve the Catholic and evangelical faith of the one Church, to the end of visible Christian unity throughout the world. news | February 12, 2017 Prayer, Protest Greet President Trump The Jan. 20 inauguration of Donald diversity of views, some of which have Trump as the 45th president of the been born in deep pain,” he said. -

Diwylliant, Y Gymraeg a Chwaraeon the National Assembly for Wales the Culture, Welsh Language and Sport Committee

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru Y Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chwaraeon The National Assembly for Wales The Culture, Welsh Language and Sport Committee Dydd Iau, 30 Tachwedd 2006 Thursday, 30 November 2006 Cynnwys Contents Cyflwyniad, Ymddiheuriadau, Dirprwyon a Datgan Buddiannau Introduction, Apologies, Substitutions and Declarations of Interest Cofnodion y Cyfarfod Diwethaf a Hynt y Camau i’w Cymryd Minutes of Last Meeting and Progress on Action Points Adroddiad Blynyddol i’r Pwyllgor gan Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru Annual Report to Committee from National Museum Wales Adroddiad Blynyddol i’r Pwyllgor gan Lyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru Annual Report to Committee from National Library of Wales Cronfeydd Diwylliannol Ewrop European Cultural Funds Cynnig Trefniadol Procedural Motion Cofnodir y trafodion hyn yn yr iaith y llefarwyd hwy ynddi yn y pwyllgor. Yn ogystal, cynhwysir cyfieithiad Saesneg o gyfraniadau yn y Gymraeg. These proceedings are reported in the language in which they were spoken in the committee. In addition, an English translation of Welsh speeches is included. Aelodau Cynulliad yn bresennol: Rosemary Butler (Cadeirydd), Eleanor Burnham, Lisa Francis, Denise Idris Jones, Val Lloyd, Alun Pugh (y Gweinidog dros Ddiwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chwaraeon), Owen John Thomas. Swyddogion yn bresennol: Neil Cox, Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau; Gwilym Evans, Cyfarwyddwr Dros Dro y Gyfarwyddiaeth dros Ddiwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chwaraeon; Gwyn Griffiths, Cynghorydd Cyfreithiol y Pwyllgor; Ann John, Pennaeth, Cangen y Llyfrgell Genedlaethol a’r Amgueddfa Genedlaethol; Nia Lewis, Swyddfa Ewrop, Brwsel. Eraill yn bresennol: Andrew Green, Llyfrgellydd Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru; Robin Gwyn, Cyfarwyddwr Cyfathrebu Amgueddfa Cymru; Michael Houlihan, Cyfarwyddwr Cyffredinol Amgueddfa Cymru; Judith Ingram, Pennaeth Polisi a Chynllunio Amgueddfa Cymru; Dr R. -

7432 La Traversee

(LYRCD 7432) LA TRAVERSEE Sandra Reid, vocals songs performed in their original languages Traditional songs from France, Celtic Brittany, Canada and Louisiana Featuring: Jerry O'Sullivan; uilleann pipes and penny whistle, Nilson Matta; Jared Egan; bass, Sean Harkness; guitar, Amy Platt; tenor sax, clarinets, Randy Crafton; percussion, Amit Chatterjee; tampura, Chris Cunningham; sintir, Michelle Kinney; cello, Jon Kass; fiddle, Jorge Alfano; kena, Wayne Hankin; gems horn During the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, even as English-speaking settlers were moving westward into North America from the original British colonies on the Atlantic coast, the Kingdom of France was sending it's own great wave of colonists into the South and Midwest of the continent, as well as into the original New France in Canada. Trappers, traders with the Indians, small farmers, transported convicts or footloose adventurers, their settlements sprang up along the shores of the Mississippi, the Missouri and the St. Lawrence, extending the presence of French culture over a vast area. Although the Seven Years' War of the 1750's checked the presence of French political ambitions in North America and tipped the balance in favour of English-speakers, place names like Detroit, Terre Haute, Fond du Lac and Des Moines scattered across the map of the United States bear witness to the far reach of the French influence in 1 centuries gone by. In Quebec and Louisiana, however, and in some parts of the other Canadian provinces and of New England, French culture is still a living part of the local heritage. The settlers brought with them songs and dances that were popular in France in the 1600's and 1700's. -

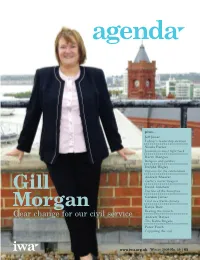

Gill Morgan, Is Dealing with Whitehall Arrogance

plus… Jeff Jones Labour’s leadership election Nicola Porter Journalism must fight back Barry Morgan Religion and politics Dafydd Wigley Options for the referendum Andrew Shearer Garlic’s secret weapon Gill David Culshaw Decline of the honeybee Gordon James Coal in a warm climate Morgan Katija Dew Beating the crunch Gear change for our civil service Andrew Davies The Kafka Brigade Peter Finch Capturing the soul www.iwa.org.uk Winter 2009 No. 39 | £5 clickonwales ! Coming soon, our new website www. iwa.or g.u k, containing much more up-to-date news and information and with a freshly designed new look. Featuring clickonwales – the IWA’s new online service providing news and analysis about current affairs as it affects our small country. Expert contributors from across the political spectrum will be commissioned daily to provide insights into the unfolding drama of the new 21 st Century Wales – whether it be Labour’s leadership election, constitutional change, the climate change debate, arguments about education, or the ongoing problems, successes and shortcomings of the Welsh economy. There will be more scope, too, for interactive debate, and a special section for IWA members. Plus: Information about the IWA’s branches, events, and publications. This will be the must see and must use Welsh website. clickonwales and see where it takes you. clickonwales and see how far you go. The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges core funding from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust , the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation . The following organisations are corporate members: Private Sector • Principality Building Society • The Electoral Commission Certified Accountants • Abaca Ltd • Royal Hotel Cardiff • Embassy of Ireland • Autism Cymru • Beaufort Research • Royal Mail Group Wales • Fforwm • Cartrefi Cymunedol / • Biffa Waste Services Ltd • RWE NPower Renewables • The Forestry Commission Community Housing Cymru • British Gas • S. -

Ritual Details of the Irish Horse Sacrifice in Betha Mholaise Daiminse

Ritual Details of the Irish Horse Sacrifice in Betha Mholaise Daiminse David Fickett-Wilbar Durham, New Hampshire [email protected] The kingly inauguration ritual described by Gerald of Wales has often been compared with horse sacrifice rituals in other Indo-European traditions, in particular the Roman October Equus and the Vedic aßvamedha. Among the doubts expressed about the Irish account is that it is the only text that describes the ritual. I will argue, however, that a similar ritual is found in another text, the Irish Life of St. Molaise of Devenish (Betha Mholaise Daiminise), not only confirming the accuracy of much of Gerald’s account, but providing additional details. Gerald of Wales’ (Gerald Cambrensis’) description of “a new and outlandish way of confirming kingship and dominion” in Ireland is justly famous among Celticists and Indo-European comparativists. It purports to give us a description of what can only be a pagan ritual, accounts of which from Ireland are in short supply, surviving into 12th century Ireland. He writes: Est igitur in boreali et ulteriori Uitoniae parte, scilicet apud Kenelcunnil, gens quaedam, quae barbaro nimis et abominabili ritu sic sibi regem creare solet. Collecto in unum universo terrae illius populo, in medium producitur jumentum candidum. Ad quod sublimandus ille non in principem sed in beluam, non in regem sed exlegem, coram omnibus bestialiter accedens, non minus impudenter quam imprudenter se quoque bestiam profitetur. Et statim jumento interfecto, et frustatim in aqua decocto, in eadam aqua balneum ei paratur. Cui insidens, de carnibus illis sibi allatis, circumstante populo suo et convescente, comedit ipse. -

MS 288 Morris Papers

MS 288 Morris Papers Title: Morris Papers Scope: Papers and correspondence of Brian Robert Morris, 4th Dec 1930-30 April 2001: academic, broadcaster, chairman/member of public and private Arts and Heritage related organizations and Life Peer, with some papers relating to his father Dates: 1912-2002 Level: Fonds Extent: 45 boxes Name of creator: Brian Robert Morris, Lord Morris of Castle Morris Administrative / biographical history: The collection comprises the surviving personal and working papers, manuscripts and associated correspondence relating to the life and work of Brian Robert Morris, university teacher and professor of English Literature, University Principal, writer, broadcaster and public figure through his membership/chairmanship of many public and private cultural bodies and his appointment to the House of Lords. He was born in 1930 in Cardiff, his father being a Pilot in the Bristol Channel, who represented the Pilots on the Cardiff Pilotage Authority, was a senior Mason and was active in the Baptist Church. Brian attended Marlborough Road School, where one of his masters was George Thomas, later Speaker of the House of Commons, and then Cardiff High School. He was brought up monolingual in English and though he learnt Welsh in later life, especially while at Lampeter, no writings in Welsh survive in the archive. He served his National Service with the Welch Regiment, based in Brecon and it was in Brecon Cathedral that his conversion to Anglicanism from his Baptist upbringing, begun as he accompanied his future wife to Church in Wales services, was completed. Anglicanism remained a constant part of his life: he became a Lay Reader when in Reading, was a passionate advocate of the Book of Common Prayer and a fierce critic of Series Three and the New English Bible, as epitomised in the book he edited in 1990, Ritual Murder . -

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = the National Library of Wales Cymorth Chwilio | Finding

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Emyr Humphreys Papers, (GB 0210 EMYREYS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/emyr-humphreys-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/emyr-humphreys-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Emyr Humphreys Papers, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad -

Fellows Elected April 2019 Honorary Fellow

The Learned Society of Wales Cymdeithas Ddysgedig Cymru The University Registry Cofrestrfa’r Brifysgol King Edward VII Avenue Rhodfa’r Brenin Edward VII Cathays Park Parc Cathays Cardiff CF10 3NS Caerdydd CF10 3NS 029 2037 6971/6954 029 2037 6971/6954 [email protected] [email protected] www.learnedsociety.wales www.cymdeithasddysgedig.cymru To: All Fellows 8 May 2019 Dear Fellow Annual General Meeting, 22 May 2019 The Annual General Meeting of the Learned Society of Wales will be held in the Physiology A Lecture Theatre in the Sir Martin Evans Building, Cardiff University (located on Museum Avenue, Cardiff CF10 3AX), on Wednesday, 22 May 2019 at 3.45 p.m. Further information regarding the location can be found at: https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/visit/accessibility/cathays-park-campus/sir-martin-evans-building Please click on ‘University Maps’ on the right hand side of the page and search for ‘Sir Martin Evans Building’ in the list of locations again on the right hand side of the page. There will be a simultaneous translation service available during the meeting and Fellows are welcome to address the Annual General Meeting in either the English language or the Welsh language. During the meeting, newly-elected Fellows who are present (and any Founding Fellows and Fellows elected between 2011 and 2018 who have not yet been formally introduced) will be formally welcomed and introduced. Their names will be read out in turn and each will be greeted by the President and will sign the Roll of Fellows. It is important, therefore, that the list of Fellows present is accurate.