The Letters of John Forster to Thomas Carlyle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus EMU, October 4, 1976

Newsline Sportsline 487·2460 487·3279 Produced by the Office of Information �rvices ferEastern Michigan University Faculty and Staff Volume 22 - Number 9 v October 4, 1976 @rornowm� Olympic Champion Crawford @ffil])&,DDil@� ) The Center of Educational Resources To Be Honored Saturday (University Library) will conduct a book sale from 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 7, in the library lobby. By Kathy Tinney Duplicates of gift books will be sold. By proclamationof the-Board of Regents,Saturday, Oct. 9, will Books on education, history, political be celebratedas HaselyCrawfordDay on campus. Crawford will be science, psychology and fiction will be honored at half-time of the Homecoming football game between included in the sale. Eastern and Arkansas State and at a reception at theHoliday Inn *** East following the game. Everyone is welcome to attend the reception. He also willserve as Grand Marshal of theHomecoming The Office of Academic Records and Parade Saturday morning. Teacher Certification reports the Crawford, "theworld's fastesthuman," won a gold medal for his following summary of degrees and native Trinidad in the 100-meterdash at the MontrealOlympics last certificates awarded as of Aug. 20, summer, beating Jamaica's Don Quarrie, Russia's Valery Borzov, 1976: B.A.-13; B.S.-208; B.A.E.-2; the defendinggold medalist, and theUnited States' Harvey Glance. B.B.E.-3; B.F.A.-16; B.B.A.-71; M.A.- In 1972 at the Munich Olympics, Crawford qualified as a finalist 460; M.SAil; M.B.E.-6; M.B.A.-10; in the 100-meter dash, but failed to finish the race due to an injury. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Robert Squire Generation No. 1 1. ROBERT1 SQUIRE was born Abt. 1650 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England, and died 26 Nov 1702 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married MARY. She died 24 Oct 1701 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. Child of ROBERT SQUIRE and MARY is: 2. i. FRANCIS2 SQUIRE, b. 1670, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. Generation No. 2 2. FRANCIS2 SQUIRE (ROBERT1) was born 1670 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married (1) MARGARET TROWING 17 May 1694 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. She was born Abt. 1670 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England, and died Jun 1700 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married (2) ESTER GEATON 06 Jan 1703 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. She was born 1676 in St Giles in the Wood, and died 1750 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. More About FRANCIS SQUIRE: Baptism: 18 Oct 1670, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England Notes for MARGARET TROWING: Name could be Margaret Crowling. More About FRANCIS SQUIRE and MARGARET TROWING: Marriage: 17 May 1694, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England More About ESTER GEATON: Baptism: 21 May 1676, St Giles in the Wood Burial: 24 Apr 1750, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England More About FRANCIS SQUIRE and ESTER GEATON: Marriage: 06 Jan 1703, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England Children of FRANCIS SQUIRE and MARGARET TROWING are: i. -

The Gentleman's Library Sale

Montpelier Street, London I 12-13 February 2020 Montpelier Street, The Gentleman’s Library Sale Library The Gentleman’s The Gentleman’s Library Sale I Montpelier Street, London I 12-13 February 2020 25762 The Gentleman’s Library Sale Montpelier Street, London | Wednesday 12 - Thursday 13 February 2020 Wednesday 12 February, 10am Thursday 13 February, 10am Silver: Lots 1 to 287 Furniture, Carpets, Works of Art, Clocks: Lots 455 to 736 Wednesday 12 February, 2pm Books: Lots 288 to 297 Pictures: Lots 298 to 376 Collectors: 377 to 454 BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PRESS ENQUIRIES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street Senior Sale Coordinator [email protected] In February 2014 the United Knightsbridge Astrid Goettsch States Government announced London SW7 1HH +44 (0)20 7393 3975 CUSTOMER SERVICES the intention to ban the import www.bonhams.com [email protected] Monday to Friday of any ivory into the USA. Lots 8.30am – 6pm containing ivory are indicated by VIEWING Carpets +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 the symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 7 February, Helena Gumley-Mason Lot number in this catalogue. 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 8963 2845 SALE NUMBER REGISTRATION Sunday 9 February, [email protected] 25762 11am to 3pm IMPORTANT NOTICE Monday 10 February Furniture Please note that all customers, CATALOGUE 9am to 4.30pm Thomas Moore irrespective of any previous activity £15 Tuesday 11 February +44 (0) 20 8963 2816 with Bonhams, are required to 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] complete the Bidder Registration Please see page 2 for bidder Form in advance of the sale. -

Conference Abstracts Conference Abstracts

Conference Abstracts VictoriansVictorians Unbound:Unbound: ConnectionsConnections andand IntersectionsIntersections BishopBishop GrossetesteGrosseteste University,University, LincolnLincoln 2222ndnd –– 2424thth AugustAugust 20172017 0 Cover Image is The Prodigal Daughter, oil on canvas (1903) by John Maler Collier (1850 – 1934), a painting you can admire at The Collection and Usher Gallery, in Danes Terrace, Lincoln, LN2 1LP: www.thecollectionmuseum.com We are grateful to The Collection: Art and Archaeology in Lincolnshire (Usher Gallery, Lincoln) for giving us the permission to use this image. We thank Dawn Heywood, Collections Development Officer, for her generous help. 1 Contents BAVS 2017 Conference Organisers p. 3 BAVS 2017 Keynote Speakers p. 4 BAVS 2017 Opening Round Table Speakers p. 7 BAVS 2017 Delegates’ Abstracts Day One p. 9 BAVS 2017 Delegates’ Abstracts Day Two p. 27 BAVS 2017 Delegates’ Abstracts Day Three p. 70 BAVS 2017 President Panel p. 88 BAVS Annual Conference 2017 Online p. 89 BAVS Annual Conference 2017 WI-FI Access p. 89 BAVS 2017 Conference Helpers p. 90 Please note, Delegates’ email addresses are available together with their abstracts. 2 BAVS Annual Conference 2017 Victorians Unbound: Connections and Intersections Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln Organising Committee Dr Claudia Capancioni (chair), Bishop Grosseteste University Dr Alice Crossley (chair), University of Lincoln Dr Cassie Ulph, Bishop Grosseteste University Rosy Ward (administrator), Bishop Grosseteste University Organising Committee Assistants -

SUBMISSION RE-EDIT Caitlin Thompson Dissertation 2019

Making ‘fritters with English’: Functions of Early Modern Welsh Dialect on the English Stage by Caitlin Thompson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre, and Performance Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Caitlin Thompson 2019 Making ‘fritters with English’: Functions of Early Modern Welsh Dialect on the English Stage Caitlin Thompson Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre, and Performance Studies University of Toronto 2019 ABSTRACT The Welsh had a unique status as paradoxically familiar ‘foreigners’ throughout early modern London; Henry VIII actively suppressed the use of the Welsh language, even though many in the Tudor line selectively boasted of Welsh ancestry. Still, in the late-sixteenth century, there was a surge in London’s Welsh population which coincided with the establishment of the city’s commercial theatres. This timely development created a stage for English playwrights to dramatically enact the complicated relationship between the nominally unified nations. Welsh difference was often made theatrically manifest through specific dialect conventions or codified and inscrutable approximate Welsh language. This dissertation expands upon critical readings of Welsh characters written for the English stage by scholars such as Philip Schwyzer, Willy Maley, and Marissa Cull, to concentrate on the vocal and physical embodiments of performed Welshness and their functions in contemporary drama. This work begins with a historicist reading of literary and political Anglo-Welsh relations to build a clear picture of the socio-historical context from which Welsh characters of the period were constructed. The plays which form the focus of this work range from popular plays like Shakespeare’s Henry V (1599) to lesser-known works from Thomas Nashe’s Summer’s Last Will and Testament (1592) to Thomas Dekker’s The Welsh Embassador ii (1623) which illuminate the range of Welsh presentations in early modern England. -

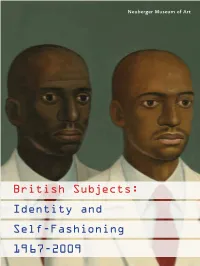

British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 for Full Functionality Please Open Using Acrobat 8

Neuberger Museum of Art British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 For full functionality please open using Acrobat 8. 4 Curator’s Foreword To view the complete caption for an illustration please roll your mouse over the figure or plate number. 5 Director’s Preface Louise Yelin 6 Visualizing British Subjects Mary Kelly 29 An Interview with Amelia Jones Susan Bright 37 The British Self: Photography and Self-Representation 49 List of Plates 80 Exhibition Checklist Copyright Neuberger Museum of Art 2009 Neuberger Museum of Art All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the publishers. Director’s Foreword Curator’s Preface British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 is the result of a novel collaboration British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 began several years ago as a study of across traditional disciplinary and institutional boundaries at Purchase College. The exhibition contemporary British autobiography. As a scholar of British and postcolonial literature, curator, Louise Yelin, is Interim Dean of the School of Humanities and Professor of Literature. I intended to explore the ways that the life writing of Britons—construing “Briton” and Her recent work addresses the ways that life writing and self-portraiture register subjective “British” very broadly—has registered changes in Britain since the Second World War. responses to changes in Britain since the Second World War. She brought extraordinary critical Influenced by recent work that expands the boundaries of what is considered under the insight and boundless energy to this project, and I thank her on behalf of a staff and audience rubric of autobiography and by interdisciplinary exchanges made possible by my institutional that have been enlightened and inspired. -

London Metropolitan Archives Irish

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 IRISH SOCIETY CLA/049 Reference Description Dates ADMINISTRATION Court minute books CLA/049/AD/01/001 Court Minute Book 24 Feb 1664/5 "Waste" or rough minute book - 1666 Aug 16 Former reference: IS/CM/1A LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 IRISH SOCIETY CLA/049 Reference Description Dates CLA/049/AD/01/002 Court Minute Book 1674 1677 Negative microfilm of this Contains repaired portions of copy deeds: not volume: MCFN/214 (formerly strictly Court minutes: Reel 1958/1). Positive copy of IS/CM/Ba: 17 consecutive folios containing same at P.R.O.N.I. This volume copy documents relating to farm letting the Irish is labelled on the microfilm under Society's rents in Londonderry and Coleraine: its former reference of "IS/CM 1 a fos. 1-4: advertisement referring to Letters -b". Patent of 10 Apr 14 Chas II [1662] and to Letters Patent of even date releasing rents and arrears at 25 Mar 1665 and to the surrender by the I.S. of customs, etc., stating conditions for farm letting the I.S. fishings for 7 years from 25 Mar 1676, and that proposals would be received on 12 Aug 1674 (advertisement dated 2 June 1674); fo. 4: George Squire's offer and acceptance 12 Aug 1674; fo. 4b: bond of George Squire and William Holgate 12 Aug 1674; fos. 5-13b: letter of I.S. attorney to George Squire with schedule of rent rolls of Londonderry and Coleraine 7 Oct 1674; fos. 14-17b: articles of agreement between I.S. -

Grabmalsskulpturen Von Louis François Roubiliac

Grabmalsskulpturen von Louis François Roubiliac Band I, Text Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Sabine Boebé aus Erftstadt Bonn 2011 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: 1. Gutachter: Prof. H. Kier 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. A. Bonnet Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 21. Juni 2010 Grabmalsskulpturen von Louis François Roubiliac GLIEDERUNG 1.0 VORBEMERKUNGEN 1 2.0 ROUBILIAC IN DER FACHLITERATUR 4 3.0 ROUBILIACS LEBEN 9 3.1 Herkunft. Familie 9 3.2 Erste Lehrjahre 11 3.3 Lehrjahre bei Balthasar Permoser 12 3.4 In der Werkstatt von Nicholas Coustou 15 3.5 Tätigkeit in Rouen 17 3.6 Exilort London 18 4.0 DER KÜNSTLER ROUBILIAC 25 4.1 Roubiliacs Arbeitsweise 25 4.2 Wirtschaftliche Lage 28 4.3 Verbindung zu Bildhauerkollegen 29 4.4 Ausbildung von Schülern 32 4.5 Lehramt an der St. Martin’s-Lane-Academy 33 4.6 Zeitgenössische Aussagen über Roubiliacs Kunst 34 5.0 ROUBILIACS ARBEITSBEREICHE 37 5 1 Büsten 37 6.0 ROUBILIACS GRABMALE MIT FIGUREN 41 6.1 Grabmal für Hough, Worcester 42 6.2 Grabmal für Argyll, London 51 6.3 Monument für Wade, London 60 6.4 Grabmal für Duke Montagu, Warkton 63 6.5 Monument für Cowper, Hertingfordbury 67 6.6 Grabmal für Myddleton, Wrexham 70 6.7 Grabmal für Mary, Duchess Montagu, Warkton 75 6.8 Monument für Fleming, London 79 6.9 Monument für Hargrave, London 82 6.10 Grabmal für Warren, London 86 6.11 -

LOCANTRO Theatre

Tony Locantro Programmes – Theatre MSS 792 T3743.L Theatre Date Performance Details Albery Theatre 1997 Pygmalion Bernard Shaw Dir: Ray Cooney Roy Marsden, Carli Norris, Michael Elphick 2004 Endgame Samuel Beckett Dir: Matthew Warchus Michael Gambon, Lee Evans, Liz Smith, Geoffrey Hutchins Suddenly Last Summer Tennessee Williams Dir: Michael Grandage Diana Rigg, Victoria Hamilton 2006 Blackbird Dir: Peter Stein Roger Allam, Jodhi May Theatre Date Performance Details Aldwych Theatre 1966 Belcher’s Luck by David Mercer Dir: David Jones Helen Fraser, Sebastian Shaw, John Hurt Royal Shakespeare Company 1964 (The) Birds by Aristophanes Dir: Karolos Koun Greek Art Theatre Company 1983 Charley’s Aunt by Brandon Thomas Dir: Peter James & Peter Wilson Griff Rhys Jones, Maxine Audley, Bernard Bresslaw 1961(?) Comedy of Errors by W. Shakespeare Christmas Season R.S.C. Diana Rigg 1966 Compagna dei Giovani World Theatre Season Rules of the Game & Six Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello Dir: Giorgio de Lullo (in Italian) 1964-67 Royal Shakespeare Company World Theatre Season Brochures 1964-69 Royal Shakespeare Company Repertoire Brochures 1964 Royal Shakespeare Theatre Club Repertoire Brochure Theatre Date Performance Details Ambassadors 1960 (The) Mousetrap Agatha Christie Dir: Peter Saunders Anthony Oliver, David Aylmer 1983 Theatre of Comedy Company Repertoire Brochure (including the Shaftesbury Theatre) Theatre Date Performance Details Alexandra – Undated (The) Platinum Cat Birmingham Roger Longrigg Dir: Beverley Cross Kenneth -

Publications April 12.Indd

2011 REPORT V&A RESEARCH MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Both as a value and an activity, research is central to the mission of the V&A. The generation of new ideas, knowledge and narratives about art and design – always grounded in our own collections – is a key objective in all our work. The V&A Research Report 2011 records outputs in all formats, from books and articles to web-based projects, exhibitions, and media appearances. These range widely across the various intellectual disciplines pertinent to the museum’s collections, and across the Collections, Conservation and Learning departments. Here you will find listings of scholarly journal articles on specific objects and artists, but also far-reaching studies of art and design across multiple centuries and places. As a global museum, we encourage our staff to think broadly, and this Report bears testimony to their success in doing just that. Collaborations are crucial to the V&A’s ongoing success, and the museum maintains formal relations with many external partners, including universities, companies, foundations, and other museums. The Research Report lists these various affiliations, which collectively demonstrate the interconnectedness of current object-based research. Entries in Italian, French, Spanish, German and Japanese, as well as activities in China, India, and the Middle East emphasise the international nature and reach of the work of the V&A. Martin Roth BOOKS, AND ARTICLES BOOKS, TO CONTRIBUTIONS BOOKS, HISTORY OF HISTORY OF ART BEFORE 1600 1800-1900 1900-PRESENT 1800-1900 ARCHITECTURE EUROPE EVANS, MARK BRITAIN Catalogue entry no.42, Jean Bourdichon. In: MARSDEN, CHRISTOPHER Martha Wolff, ed. -

Shakespeare on Film and Television in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

SHAKESPEARE ON FILM AND TELEVISION IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by Zoran Sinobad January 2012 Introduction This is an annotated guide to moving image materials related to the life and works of William Shakespeare in the collections of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. While the guide encompasses a wide variety of items spanning the history of film, TV and video, it does not attempt to list every reference to Shakespeare or every quote from his plays and sonnets which have over the years appeared in hundreds (if not thousands) of motion pictures and TV shows. For titles with only a marginal connection to the Bard or one of his works, the decision what to include and what to leave out was often difficult, even when based on their inclusion or omission from other reference works on the subject (see below). For example, listing every film about ill-fated lovers separated by feuding families or other outside forces, a narrative which can arguably always be traced back to Romeo and Juliet, would be a massive undertaking on its own and as such is outside of the present guide's scope and purpose. Consequently, if looking for a cinematic spin-off, derivative, plot borrowing or a simple citation, and not finding it in the guide, users are advised to contact the Moving Image Reference staff for additional information. How to Use this Guide Entries are grouped by titles of plays and listed chronologically within the group by release/broadcast date. -

Timon of Athens

Rolf Soellner TIMON OF ATHENS Shakespeare's Pessimistic Tragedy $15.50 TIMON OF ATHENS Shakespeare's Pessimistic Tragedy By Rolf Soellner With a Stage History by Gary Jay Williams Perhaps the most problematical of Shake speare's tragedies opens on a distinctly ominous if nonetheless casual note. A poet and a painter meet and, after exchanging greetings, the former asks, "How goes the world?" Whereupon the painter replies, "It wears, sir, as it grows" — to which the poet responds, as to a cliche, "Ay, that's well known." The notion of the world's decay, a sur vivor of the contempus mundi of medieval philosophy, with its groundings in concep tions of the Fall and Last Judgment, achieved a renewed ascendancy in the dark ening climate of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. And it is, Professor Soellner points out, only in the mood and tenor engendered by this pervasive pes simism, which many critics of Timon have found uncongenial, that we can come fully to understand Shakespeare's misanthrope, who has been much maligned as the inferior of Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello, and Lear, but who is, if not entirely their equal, an authen tic tragic hero in his own right. Professor Soellner accepts Timon as a tragedy, albeit one that does not necessarily satisfy standard definitions; and though he readily concedes that there are sporadic tex tual deficiencies, he finds in the structure of the play, its characterization, imagery, and thematic development, the imprint of Shakespeare's incomparable genius and the indisputable evidence of the drama's having been meticulously worked out in conformity with a controlling and high tragic design.