SUBMISSION RE-EDIT Caitlin Thompson Dissertation 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through the Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through The Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time Emma Givens Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Theatre History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4826 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Emma Givens 2017 All rights reserved A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through The Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Emma Pedersen Givens Director: Noreen C. Barnes, Ph.D. Director of Graduate Studies Department of Theatre Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia March, 2017 ii Acknowledgement Theatre is a collaborative art, and so, apparently, is thesis writing. First and foremost, I would like to thank my grandmother, Carol Pedersen, or as I like to call her, the world’s greatest research assistant. Without her vast knowledge of everything Shakespeare, I would have floundered much longer. Thank you to my mother and grad-school classmate, Boomie Pedersen, for her unending support, my friend, Casey Polczynski, for being a great cheerleader, my roommate, Amanda Long for not saying anything about all the books littered about our house and my partner in theatre for listening to me talk nonstop about Shakespeare over fishboards. -

12. What We Talk About When We Talk About Indian

12. What we talk about when we talk about Indian Yvette Nolan here are many Shakespearean plays I could see in a native setting, from A Midsummer Night’s Dream to Coriolanus, but Julius Caesar isn’t one of them’, wrote Richard Ouzounian in the Toronto Star ‘Tin 2008. He was reviewing Native Earth Performing Arts’ adaptation of Julius Caesar, entitled Death of a Chief, staged at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, Toronto. Ouzounian’s pronouncement raises a number of questions about how Indigenous creators are mediated, and by whom, and how the arbiter shapes the idea of Indigenous.1 On the one hand, white people seem to desire a Native Shakespeare; on the other, they appear to have a notion already of what constitutes an authentic Native Shakespeare. From 2003 to 2011, I served as the artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts, Canada’s oldest professional Aboriginal theatre company. During my tenure there, we premiered nine new plays and a trilingual opera, produced six extant scripts (four of which we toured regionally, nationally or internationally), copresented an interdisciplinary piece by an Inuit/Québecois company, and created half a dozen short, made-to-order works, community- commissioned pieces to address specific events or issues. One of the new plays was actually an old one, the aforementioned Death of a Chief, which we coproduced in 2008 with Canada’s National Arts Centre (NAC). Death, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, took three years to develop. Shortly after I started at Native Earth, Aboriginal artists approached me about not being considered for roles in Shakespeare (unless producers were doing Midsummer Night’s Dream, because apparently fairies can be Aboriginal, or Coriolanus, because its hero struggles to adapt to a consensus-based community). -

For God's Sake, Let Us Sit Upon the Ground and Tell Sad Stories of the Death of Kings … -Richard II, Act III, Scene Ii

The Hollow Crown is a lavish new series of filmed adaptations of four of Shakespeare’s most gripping history plays: Richard II , Henry IV, Part 1 , Henry IV, Part 2 , and Henry V , presented by GREAT PERFORMANCES . For God's sake, let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings … -Richard II, Act III, Scene ii 2013 WNET Synopsis The Hollow Crown presents four of Shakespeare’s history plays: Richard II , Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, and Henry V . These four plays were written separately but tell a continuous story of the reigns of three kings of England. The first play starts in 1398, as King Richard arbitrates a dispute between his cousin Henry Bolingbroke and the Duke of Norfolk, which he resolves by banishing both men from England— Norfolk for life and Bolingbroke for six years. When Bolingbroke’s father dies, Richard seizes his lands. It’s the latest outrage from a selfish king who wastes money on luxuries, his favorite friends, and an expensive war in Ireland. Bolingbroke returns from banishment with an army to take back his inheritance and quickly wins supporters. He takes Richard prisoner and, rather than stopping at his own lands and privileges, seizes the crown. When one of Bolingbroke’s followers assassinates Richard, the new king claims that he never ordered the execution and banishes the man who killed Richard. Years pass, and at the start of Henry IV, Part 1 , the guilt-stricken king plans a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to wash Richard’s blood from his hands. -

The Life of King Henry the Fifth Study Guide

The Life of King Henry the The Dukes of Gloucester and Fifth Bedford: The Study Guide King’s brothers. Compiled by Laura Cole, Duke of Exeter: Director of Education and Training Uncle to the [email protected] King. for The Atlanta Shakespeare Company Duke of York: at The New American Shakespeare Cousin to the King. Tavern Earl’s of Salisbury, Westmoreland and 499 Peachtree Street, NE Warwick: Advisors to the King. Atlanta, GA 30308 Phone: 404-874-5299 The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Ely: They know the Salic Law very well! www.shakespearetavern.com The Earl of Cambridge, Sir Thomas Grey and Lord Scroop: English traitors, they take gold Original Practice and Playing from France to kill the King, but are discovered. Scroop is a childhood friend of Henry’s. Shakespeare Gower, Fluellen, Macmorris and Jamy: Captains in the King’s army, English, Welsh, The Shakespeare Tavern on Peachtree Street Irish and Scottish. is an Original Practice Playhouse. Original Practice is the active exploration and Bates, Court, Williams: Soldiers in the King’s implementation of Elizabethan stagecraft army. and acting techniques. Nym, Pistol, Bardolph: English soldiers and friends of the now-dead Falstaff, as well as For the Atlanta Shakespeare Company drinking companions of Henry, when he was (ASC) at The New American Shakespeare Prince Hal. A boy also accompanies the men. Tavern, this means every ASC production features hand-made period costumes, live Hostess of the Boar’s Head Tavern: Nee’ actor-generated sound effects, and live Quickly, now married to Pistol. period music performed on period Charles IV of France: The King of France. -

Focus EMU, October 4, 1976

Newsline Sportsline 487·2460 487·3279 Produced by the Office of Information �rvices ferEastern Michigan University Faculty and Staff Volume 22 - Number 9 v October 4, 1976 @rornowm� Olympic Champion Crawford @ffil])&,DDil@� ) The Center of Educational Resources To Be Honored Saturday (University Library) will conduct a book sale from 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 7, in the library lobby. By Kathy Tinney Duplicates of gift books will be sold. By proclamationof the-Board of Regents,Saturday, Oct. 9, will Books on education, history, political be celebratedas HaselyCrawfordDay on campus. Crawford will be science, psychology and fiction will be honored at half-time of the Homecoming football game between included in the sale. Eastern and Arkansas State and at a reception at theHoliday Inn *** East following the game. Everyone is welcome to attend the reception. He also willserve as Grand Marshal of theHomecoming The Office of Academic Records and Parade Saturday morning. Teacher Certification reports the Crawford, "theworld's fastesthuman," won a gold medal for his following summary of degrees and native Trinidad in the 100-meterdash at the MontrealOlympics last certificates awarded as of Aug. 20, summer, beating Jamaica's Don Quarrie, Russia's Valery Borzov, 1976: B.A.-13; B.S.-208; B.A.E.-2; the defendinggold medalist, and theUnited States' Harvey Glance. B.B.E.-3; B.F.A.-16; B.B.A.-71; M.A.- In 1972 at the Munich Olympics, Crawford qualified as a finalist 460; M.SAil; M.B.E.-6; M.B.A.-10; in the 100-meter dash, but failed to finish the race due to an injury. -

Shakespeare's

Shakespeare’s Henry IV: s m a r t The Shadow of Succession SHARING MASTERWORKS OF ART April 2007 These study materials are produced for use with the AN EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH OF BOB JONES UNIVERSITY Classic Players production of Henry IV: The Shadow of Succession. The historical period The Shadow of Succession takes into account is 1402 to 1413. The plot focuses on the Prince of Wales’ preparation An Introduction to to assume the solemn responsibilities of kingship even while Henry IV regards his unruly son’s prospects for succession as disastrous. The Shadow of When the action of the play begins, the prince, also known as Hal, finds himself straddling two worlds: the cold, aristocratic world of his Succession father’s court, which he prefers to avoid, and the disreputable world of Falstaff, which offers him amusement and camaraderie. Like the plays from which it was adapted, The Shadow of Succession offers audiences a rich theatrical experience based on Shakespeare’s While Henry IV regards Falstaff with his circle of common laborers broad vision of characters, events and language. The play incorporates a and petty criminals as worthless, Hal observes as much human failure masterful blend of history and comedy, of heroism and horseplay, of the in the palace, where politics reign supreme, as in the Boar’s Head serious and the farcical. Tavern. Introduction, from page 1 Like Hotspur, Falstaff lacks the self-control necessary to be a produc- tive member of society. After surviving at Shrewsbury, he continues to Grieved over his son’s absence from court at a time of political turmoil, squander his time in childish pleasures. -

Reader's Digest Canada

MOST READ MOST TRUSTED SEPTEMBER 2015 A ROYAL RECORD PAGE 56 HOW TO GREEK BOOST FERRY LEARNING DISASTER PAGE 70 PAGE 78 TIPS FOR A HEALTHY BEDROOM PAGE 102 WORRY: IT’S GOOD FOR YOU! PAGE 27 WHEN TO BUY ORGANIC PAGE 40 BE NICE TO YOUR KNEES .................................. 30 MIND-BENDING PUZZLES ................................ 129 LAUGHTER, THE BEST MEDICINE ..................... 68 ALL THE CRITICS SAY “YEAH!” THE REVIEWS ARE IN... “ SPECTACULAR CELEBRATION!” Richard Ouzounian, Toronto Star “FABULOUS, FUNNY “ONE OF THE BEST & FANTASTIC! MUSICALS I’VE EVER SEEN. DON’T MISS THIS ONE!” KINKYs crazy BOOTSgood.” i Jennifer Valentyne, Breakfast Television Steve Paikin, TVO A NEW MUSICAL BASED ON A TRUE STORY Tiedemann Von Cylla “A FEEL GOOD SHOW. by YOU LEAVE THE THEATRE WITH A BIG SMILE ON YOUR FACE Photos and a bounce in your high-heeled step!” Carolyn MacKenzie, Global TV NOWN STAGE O ROYAL ALEXANDRA THEATRE 260 KING STREET WEST, TORONTO 1-800-461-3333 MIRVISH.COM ALAN MINGO JR. AJ BRIDEL & GRAHAM SCOTT FLEMING Contents SEPTEMBER 2015 Cover Story 56 Mighty Monarch On September 9, Queen Elizabeth II becomes the longest-reigning ruler in British history. A Canadian look back. STÉPHANIE VERGE Society 62 Cash-Strapped Payday loans are a lifeline for low-income Canadians—but at what cost? CHRISTOPHER POLLON FROM THE WALRUS Science 70 Know Better New ways to improve your ability to learn. DANIELLE GROEN AND KATIE UNDERWOOD Drama in Real Life 78 Ship Down P. A Greek family fight to survive when their ferry | 70 goes up in flames. KATHERINE LAIDLAW Humour 86 The Endless Steps David Sedaris on becoming obsessed with Fitbit. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Robert Squire Generation No. 1 1. ROBERT1 SQUIRE was born Abt. 1650 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England, and died 26 Nov 1702 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married MARY. She died 24 Oct 1701 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. Child of ROBERT SQUIRE and MARY is: 2. i. FRANCIS2 SQUIRE, b. 1670, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. Generation No. 2 2. FRANCIS2 SQUIRE (ROBERT1) was born 1670 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married (1) MARGARET TROWING 17 May 1694 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. She was born Abt. 1670 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England, and died Jun 1700 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married (2) ESTER GEATON 06 Jan 1703 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. She was born 1676 in St Giles in the Wood, and died 1750 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. More About FRANCIS SQUIRE: Baptism: 18 Oct 1670, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England Notes for MARGARET TROWING: Name could be Margaret Crowling. More About FRANCIS SQUIRE and MARGARET TROWING: Marriage: 17 May 1694, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England More About ESTER GEATON: Baptism: 21 May 1676, St Giles in the Wood Burial: 24 Apr 1750, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England More About FRANCIS SQUIRE and ESTER GEATON: Marriage: 06 Jan 1703, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England Children of FRANCIS SQUIRE and MARGARET TROWING are: i. -

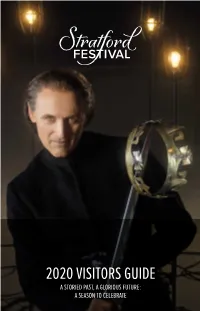

2020 Visitors Guide a Storied Past, a Glorious Future: a Season to Celebrate the Elixir of Power

2020 VISITORS GUIDE A STORIED PAST, A GLORIOUS FUTURE: A SEASON TO CELEBRATE THE ELIXIR OF POWER Irresistible – that’s the only way to describe the variety, quality and excitement that make up the Stratford Festival’s 2020 season. First, there is our stunning new Tom Patterson Theatre, with ravishingly beautiful public spaces and gardens. Its halls, bars and café will be filled throughout the season with music, comedy nights, panel discussions and outstanding speakers to make our Festival even more festive. In the wake of an election in Canada, and in anticipation of one in the U.S., our season explores the theme of Power. Recent years have seen a growing acceptance of the naked use of power. Brute force is in vogue on the world stage, from international trade to immigration and the arms race – and, closer to home, in elections, in the workplace and even in social media engagements. Through comedy, tragedy, song, dance and farce, the plays and musicals of our 2020 season explore the dynamics of power in society, politics, art, gender and family life. In our new Tom Patterson Theatre, we present the two plays that launched the Stratford adventure in 1953: All’s Well That Ends Well and Richard III. The new venue is also home to a new musical, Here’s What It Takes; a new movement-based creation, Frankenstein Revived; and a series of improvisational performances – each one unique and unrepeatable – called An Undiscovered Shakespeare. But the fun isn’t all confined to one theatre. Our historic Festival Theatre showcases two of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet, as well as Molière’s brilliant satire The Miser and the first major new production in decades of the mischievous musical Chicago. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

SUPPORT FOR THE 2021 SEASON OF THE TOM PATTERSON THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY THE HARKINS & MANNING FAMILIES IN MEMORY OF SUSAN & JIM HARKINS LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

Portraits D'institutions Culturelles Montréalaises

Portraits d’institutions culturelles montréalaises Quels modes d’action pour l’accessibilité, l’inclusion et l’équité ? La collection « Monde culturel » Liste des titres parus : propose un regard inédit sur les Ève Lamoureux et Magali Uhl, Le vivre-ensemble multiples manifestations de la à l’épreuve des pratiques culturelles et artistiques contemporaines, 2018. vie culturelle et sur la circulation des arts et de la culture dans la Benoît Godin, L’innovation sous tension. Histoire d’un concept, 2017. société. Privilégiant une approche interdisciplinaire, elle vise à Nathalie Casemajor, Marcelle Dubé, Jean-Marie Lafortune, Ève Lamoureux, Expériences critiques de la réunir des perspectives aussi bien médiation culturelle, 2017. théoriques qu’empiriques en vue Julie Dufort et Lawrence Olivier, Humour et politique, d’une compréhension adéquate des 2016. contenus culturels et des pratiques Myrtille Roy-Valex et Guy Bellavance, Arts et territoires qui y sont associées. Ce faisant, à l’ère du développement durable : Vers une nouvelle elle s’intéresse aussi bien aux économie culturelle ?, 2015. enjeux et aux problématiques qui Andrée Fortin, Imaginaire de l’espace dans le cinéma traversent le champ actuel de la québécois, 2015. culture qu’aux acteurs individuels Geneviève Sicotte, Martial Poirson, Stéphanie Loncle et Christian Biet (dir.), Fiction et économie. et collectifs qui le constituent : Représentations de l’économie dans la littérature et les artistes, entrepreneurs, médiateurs arts du spectacle, XIXe-XXIe siècles, 2013. et publics de la culture, mouve- Étienne Berthold, Patrimoine, culture et récit. L’île ments sociaux, organisations, d’Orléans et la place Royale de Québec, 2012. institutions et politiques culturelles. Centrée sur l’étude du terrain contemporain de la culture, la collection invite également à poser un regard historique sur l’évolution de notre univers culturel. -

2015 Summer Shakespeare Intensive

PRESENTS 2015 SUMMER SHAKESPEARE INTENSIVE Two one-hour versions of Shakespeare’s plays LOVE’S LABOR’S LOST & THE TEMPEST Donald and Darlene Shiley Stage Old Globe Theatre Conrad Prebys Theatre Center Monday, August 10, 2015 elcome! Tonight is a celebration. We celebrate Shakespeare, we celebrate theatre, we celebrate imagination. But most of all, we celebrate the young people performing on our stage this evening. Each year young actors walk through our doors ready to learn from us. Indeed, they do learn here. They learn about iambic pentameter, stage combat, choreography, speech, lexicons (ask one of the actors what that is), dance, and professionalism. These things are what we bring to the table. What we never fully realize until we’re in the midst of the program is that we, the directors, stage managers, and staff members, are the ones who learn the most. These extraordinary young people bring us their exuberance, their audacity, their startling honesty and courage. They force us to think again and again about what it means to be human: the very thing that theatre is all about. These young actors remind us each and every day that we must be open and loving in our interactions. They never let us forget how delicate and how powerful they are. We watch them with awe and gratitude for all that they give us. Tonight, take care to watch closely for the elegance and grace of their youth. This day is for all of us, together, to embrace our humanity and breathe in the joy of the art of living.