Bus Rapid Transit and the Use of AVL Technology: a Survey of Integrating Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

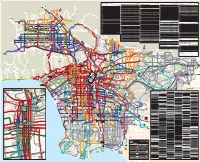

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

A Review of Reduced and Free Transit Fare Programs in California

A Review of Reduced and Free Transit Fare Programs in California A Research Report from the University of California Institute of Transportation Studies Jean-Daniel Saphores, Professor, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Department of Urban Planning and Public Policy, University of California, Irvine Deep Shah, Master’s Student, University of California, Irvine Farzana Khatun, Ph.D. Candidate, University of California, Irvine January 2020 Report No: UC-ITS-2019-55 | DOI: 10.7922/G2XP735Q Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UC-ITS-2019-55 N/A N/A 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date A Review of Reduced and Free Transit Fare Programs in California January 2020 6. Performing Organization Code ITS-Irvine 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Jean-Daniel Saphores, Ph.D., https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9514-0994; Deep Shah; N/A and Farzana Khatun 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Institute of Transportation Studies, Irvine N/A 4000 Anteater Instruction and Research Building 11. Contract or Grant No. Irvine, CA 92697 UC-ITS-2019-55 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered The University of California Institute of Transportation Studies Final Report (January 2019 - January www.ucits.org 2020) 14. Sponsoring Agency Code UC ITS 15. Supplementary Notes DOI:10.7922/G2XP735Q 16. Abstract To gain a better understanding of the current use and performance of free and reduced-fare transit pass programs, researchers at UC Irvine surveyed California transit agencies with a focus on members of the California Transit Association (CTA) during November and December 2019. -

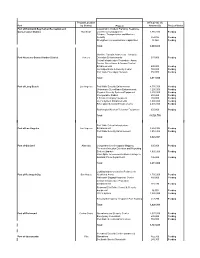

Public Transportation Modernization Improvement and Service Enhancement Account Prop 1B

State Controller's Office Division Of Accounting And Reporting Public Transportation Modernization Improvement and Service Enhancement Account Prop 1B 2008-2009 Fiscal Year Payment Issue Date: 03/15/2011 Gross Claim Total Calaveras Council of Governments: Transit Bus Stop 138,710.00 138,710.00 Facilities Central Contra Costa Transit Authority: Bus Stop Access 67,115.00 67,115.00 & Amenity Improvements City of Atascadero: Driver and Vehicle Safety 3,156.00 3,156.00 Enhancements City of Beaumont: Purchase and Install Onboard Security 81,867.00 81,867.00 Cameras City of Culver City: Purchase of 20 CNG Transit Buses 372,215.00 372,215.00 City of Eureka: GPS Tracking System 22,880.00 22,880.00 City of Folsom: Security Cameras & Engine Scanner- 12,324.00 12,324.00 Folsom City of Fresno: Bus Rapid Transit Improvements 1,467,896.00 1,467,896.00 City of Fresno: CNG Engine Retrofits 1,800,000.00 1,800,000.00 City of Fresno: FAX Paratransit Facility 129,940.00 129,940.00 City of Fresno: Passenger Amenities Bus Stop 22,000.00 22,000.00 Improvement City of Fresno: Purchase Replacement Paratransit Buses 19,500.00 19,500.00 City of Fresno: Purchase Replacement Support Vehicles 17,000.00 17,000.00 City of Fresno: Purchase/Install Shop Equipment 20,378.00 20,378.00 City of Fresno: Purchase/Install CNG Compressor 54,600.00 54,600.00 City of Healdsburg: Replacement Bus Purchase 1,053.00 1,053.00 Page 1 of 7 Gross Claim Total City of Lodi: Bus Replacements 291,409.00 291,409.00 City of Modesto: Build Bus Fare Depository 20,000.00 20,000.00 City of Modesto: -

Fiscal Year (FY) 2011–12 TRANSIT SYSTEM PERFORMANCE REPORT Understanding the Region’S Investments in Public Transportation

Fiscal Year (FY) 2011–12 TRANSIT SYSTEM PERFORMANCE REPORT Understanding the Region’s Investments in Public Transportation Transit/Rail Department PHOTO CREDITS SCAG would like to thank the ollowing transit agencies: • City o Santa Monica, Big Blue Bus • City o Commerce Municipal Bus Lines • Foothill Transit • Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) • Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA) • Omnitrans • Victor Valley Transit Authority CONTENTS SECTION 01 Public Transportation in the SCAG Region ........ 1 SECTION 02 Evaluating Transit System Performance ......... 13 SECTION 03 Operator Profiles ....................................... 31 Imperial County .................................... 32 Los Angeles County .............................. 34 Orange County ..................................... 76 Riverside County .................................. 82 San Bernardino County .......................... 93 Ventura County .................................... 99 APPENDIX A Transit Governance in the SCAG Region ......... A1 APPENDIX B System Performance Measures ................... B1 APPENDIX C Reporting Exceptions ................................. C1 SECTION 01 Public Transportation in the SCAG Region Santa Monica’s Big Blue Bus (BBB) City o Commerce Municipal Bus Lines (CBL) FY 2011-12 TRANSIT SYSTEM PERFORMANCE REPORT INTRODUCTION The Southern Cali ornia Association o Governments (SCAG) is the designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) representing six counties in Southern Cali ornia: Imperial, Los -

Smart Location Database Technical Documentation and User Guide

SMART LOCATION DATABASE TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION AND USER GUIDE Version 3.0 Updated: June 2021 Authors: Jim Chapman, MSCE, Managing Principal, Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. (UD4H) Eric H. Fox, MScP, Senior Planner, UD4H William Bachman, Ph.D., Senior Analyst, UD4H Lawrence D. Frank, Ph.D., President, UD4H John Thomas, Ph.D., U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization Alexis Rourk Reyes, MSCRP, U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization About This Report The Smart Location Database is a publicly available data product and service provided by the U.S. EPA Smart Growth Program. This version 3.0 documentation builds on, and updates where needed, the version 2.0 document.1 Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. updated this guide for the project called Updating the EPA GSA Smart Location Database. Acknowledgements Urban Design 4 Health was contracted by the U.S. EPA with support from the General Services Administration’s Center for Urban Development to update the Smart Location Database and this User Guide. As the Project Manager for this study, Jim Chapman supervised the data development and authored this updated user guide. Mr. Eric Fox and Dr. William Bachman led all data acquisition, geoprocessing, and spatial analyses undertaken in the development of version 3.0 of the Smart Location Database and co- authored the user guide through substantive contributions to the methods and information provided. Dr. Larry Frank provided data development input and reviewed the report providing critical input and feedback. The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance, review, and support provided by: • Ruth Kroeger, U.S. General Services Administration • Frank Giblin, U.S. -

September 14, 2016

ADVANCED TRANSIT VEHICLE CONSORTIUM Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority One Santa Fe Ave., MS 63-4-1, Los Angeles, CA 90013 SEPTEMBER 14, 2016 TO: BOARD OF DIRECTORS FROM: JAMES T. GALLAGHER PRESIDENT SUBJECT: RECEIVE AND FILE UPDATE ON ZERO EMISSION BUS PLANS ISSUE At the April 2016 Metro Board of Directors Meeting, Metro's CEO was asked to provide a status report on Metro's deployment plans for Zero Emission Buses, and to provide a comprehensive plan to further reduce greenhouse gas emissions by gradually transitioning to a zero emission bus fleet. BACKGROUND Metro's current deployment plan for Zero Emission Buses (ZEB's) and reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions(GHG) includes the following projects and activities: 1. Purchase of five (5) New Flyer all-electric articulated buses for deployment on Metro's Orange Line with expected delivery in late 2017. 2. Purchase of five (5) BYD all-electric articulated buses, also for use on Metro's Orange Line with expected delivery in late 2017. 3. Purchase of up to two hundred (200)ZE buses under RFP OP28167 for delivery between FY18 — FY22. 4. Expand use of Low NOx "Near Zero" CNG engines and Renewable Natural Gas (RCNG)for all new bus purchases and for mid-life engine repowers stating in FY18. In addition to the ZEB projects, starting in FY18 it is recommended that Metro Operations adopt a policy of purchasing only "Near Zero" Cummins-Westport Low NOx ISL-G engines and renewable natural gas(RCNG) fuel for both new and repowered buses. According to the fleet emission modeling done by Metro's technical consultant, this step will have significant regional air quality benefits, including reducing criteria pollutants for Metro's bus fleet by 90%, and greenhouse gas emissions by 80°/o below 2010 current fleet emission levels. -

Getting on Track: Record Transit Ridership Increases Energy Independence Getting on Track

Getting On Track: Record Transit Ridership Increases Energy Independence Getting On Track: Record Transit Ridership Increases Energy Independence Rob McCulloch Environment America Research and Policy Center Philip Faustmann and Jessica Darmawan Environment America Research and Policy Center September, 2009 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Tony Dutzik, Frontier Group and Robert Padgette, American Public Transit Association, for their review of this report. The generous financial support of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Surdna Foundation made this report possible. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. Any factual errors are strictly the responsibility of the author. © 2009 Environment America Research & Policy Center Environment America Research & Policy Center is a 501(c)(3) organization. We are dedicated to protecting America’s air, water and open spaces. We investigate problems, craft solutions, educate the public and decision makers, and help Americans make their voices heard in local, state and national debates over the quality of our environment and our lives. For more information about Environment America Research & Policy Center or for additional copies of this report, please visit www.EnvironmentAmerica.org. Cover photo: Sam Churchill Layout: Jenna Leschuk, Ampersand Mountain Creative 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Context The Relationship Between Transportation and Oil Dependence 2 Public -

Developing Statewide Sustainable-Communities Strategies Monitoring System for Jobs, Housing, and Commutes December 15, 2018 6

STATE OF CALIFORNIA • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ADA Notice TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in alternate TR0003 (REV 10/98) formats. For information call (916) 654-6410 or TDD (916) 654-3880 or write Records and Forms Management, 1120 N Street, MS-89, Sacramento, CA 95814. 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION NUMBER 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER CA 18-2931 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Developing Statewide Sustainable-Communities Strategies Monitoring System for Jobs, Housing, and Commutes December 15, 2018 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR(S) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Paul M. Ong,Chhandara Pech, Alycia Cheng, Silvia R. González 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NUMBER University of California, Los Angeles, 10889 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 700 Los Angeles, Ca 90095 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBER 65A0636 12. SPONSORING AGENCY AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED California Department of Transportation July 1, 2017 - December 31, 2018 Division of Research, Innovation and System Information PO Box942873, MS 83 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE Sacramento, CA 94273-0001 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 16. ABSTRACT This project is the second phase of a larger effort aimed at developing a group of key indicators, referred to in this document as the Statewide Monitoring System, to track progress toward achieving certain SB 375 goals across California. One of the legislation's goals is to promote better coordination of land-use, housing, and transportation planning with the goal of reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions. The proposed Statewide Monitoring System identifies key recent developments by small geographies (i.e. -

Advanced Public Transportation Systems Deployment in the United States

U.S. Department of Transportation Advanced Public Transportation Systems Deployment in the United States Update, January 1999 Advanced Public Transportation Systems Deployment in the United States Update, January 1999 Prepared for: Office of Mobility Innovation Federal Transit Administration U. S. Department of Transportation Prepared by: Office of System and Economic Assessment John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Research and Special Programs Administration U. S. Department of Transportation Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED January 1999 Final Report July 1998 - December 1998 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Advanced Public Transportation Systems Deployment in the United States TT950/U9181 6. AUTHOR(S) Robert F. Casey 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION U.S. Department of Transportation REPORT NUMBER Research and Special Programs Administration John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center DOT-VNTSC-FTA-99-1 Cambridge, MA 02142-1093 9. -

![Federal Transit Administration (FTA) ; Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS)[Distributor] 2021-03-29](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5602/federal-transit-administration-fta-bureau-of-transportation-statistics-bts-distributor-2021-03-29-3025602.webp)

Federal Transit Administration (FTA) ; Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS)[Distributor] 2021-03-29

README for “National Transit Map 2001-Present” dataset. U.S Department of Transportation (USDOT), Federal Transit Administration (FTA) ; Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS)[distributor] 2021-03-29 ---------------------------------------------------------------- LINKS TO DATASET ---------------------------------------------------------------- A. Dataset archive link: https://doi.org/10.21949/1520808 ---------------------------------------------------------------- SUMMARY OF DATASET ---------------------------------------------------------------- The General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS)/National Transit Map (NTM) dataset is 2001-Present and is from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), and part of U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT)/Bureau of Transportation Statistics' (BTS') National Transportation Atlas Database (NTAD). This dataset, also known as GTFS static or static transit to differentiate it from the GTFS real-time extension, defines a common format for public transportation schedules and associated geographic information. GTFS "feeds" let public transit agencies publish their transit data and developers write applications that consume that data in an interoperable way. GTFS Data is stored in the National Transit Map database. ---------------------------------------------------------------- TABLE OF CONTENTS ---------------------------------------------------------------- A. General Information B. Sharing/Access & Policies Information C. Data and Related File Overview D. Methodological Information E. Data-Specific -

Project Location

Project Location 8879.23 (C) (3) Port by County Project Amount ($) Project Status Port of Humboldt Bay Harbor Recreation and Catastrophic Incident Planning, Response, Conservation District Humboldt and Recovery Equipment 1,861,335 Pending Enhance Transportation and Maritime Security 664,034 Pending Strengthen Communications Capabilities 44,500 Pending Total 2,569,869 Maritime Domain Awareness - Landside Port Hueneme Oxnard Harbor District Ventura Detection Enhancements 527,000 Pending Critical Infrastructure Protection - Asset Barrier, Surveillance & Access Control Enhancements 690,000 Pending Joint Operations & Security Center 750,000 Pending Port-Wide Fiber Optic Network 850,000 Pending Total 2,817,000 Port of Long Beach Los Angeles Port-Wide Security Enhancement 4,776,750 Pending Underwater Surveillance Enhancement 1,200,000 Pending Physical Security Systems/Equipment 3,800,000 Pending Interoperable Radios 250,000 Pending 3-D Laser Imaging Equipment 150,000 Pending CCTV System Enhancements 1,000,000 Pending Fiber Optic Network Enhancements 2,000,000 Pending Radiological/Nuclear Detection Equipment 350,000 Pending Total 13,526,750 Port-Wide Critical Infrastructure Port of Los Angeles Los Angeles Enhancement 5,464,938 Pending Port-Wide Security Enhancement 4,910,989 Pending Total 9,925,927 Port of Oakland Alameda Comprehensive Geospatial Mapping 335,000 Pending Perimeter Intrusion Detection and Reporting System Upgrade 1,900,000 Pending Fiber Optic Telecommunications Linkage to Oakland Police Department 196,000 Pending Total 2,431,000 -

7 Things You (Maybe) Never Knew About Rideshare

March/April 2020 News for Your Employees Download > > Rideshare News for Southern California Employee Transportation Coordinators (ETCs) Download Spanish version 7 Things You (Maybe) Never Knew About Rideshare Get On Board Day Ever wonder how Rideshare Thursday became part of California culture? Why Thursdays? Shouldn’t every day be Rideshare Day? Here, we take a peek at how A few transit facts in honor of our favorite day of the week came to be… Get On Board Day April 16, which celebrates the many benefits of transit: Rideshare Thursday is • During rush hour, a bus of seated 1. a term first coined back passengers carries more people in 1993 as part of a Caltrans- than a one block long traffic jam. sponsored ad campaign. • A household can save nearly $10,000 While any day is a good day by taking public transportation and to rideshare, Thursdays were living with one less car. dubbed rideshare’s official day. • Riding the train emits 73% less CO2 than commuting by car. Thursdays were chosen 2. as “rideshare day” because they are overall the busiest commuter traffic day of the week, according to Ride free to the polls on Caltrans. (Fridays and Mondays typically have the least Election Day March 3 on weekday traffic due to flex schedules and people Metro Bus and Rail, as well as taking a day off to have a longer weekend.) AVTA, Culver City Bus, LADOT, Pasadena Transit and The idea behind the campaign is Long Beach Transit. 3. to remind commuters that they don’t need to rideshare every day to make a difference—even one day a week has its benefits.