Theatre Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TO TOKYO! a World Premiere Kabuki Comedy Sequel I to the Road to Kyoto! I Performed in English by an All UH Ca T

I THE ROAD I TO TOKYO! A world premiere Kabuki comedy sequel I to The Road to Kyoto! I Performed in English by an all UH ca t. Directed by James R. Brandon .I $9 Regular, $7 Discount, Nov 30 $1 UHM students with I Dec 1, 5-8, 13-15 -8 pm valid ID (not avail. by mail) I I I Dec 9, 16 -2 pm The Two I CHARGE-BY-PHONE: I Tickets on sale Nov 13 956-7655 GentleiDen of I I ORDER BY MAIL for the best seats to ROAD TO TOKYO! I -----------------DEADLINE: NOVEMBER 8, 1990 I Verona I I Name I by William Shakespeare I Street I ~ I I I City State Zip I Telephone: (Day) (Evening) I I I I would like tickets for the following show: I Fri , November 30 8 pm Sun , December 9 2 pm Matinee I I Sat, December 1 8 pm Thur, December 13 8 pm I Wed , December 5 8 pm Fri , December 14 8 pm I Thur, December 6 8 pm Sat, December 15 8 pm r Fri . December 7 8 pm Sun , December 16 2 pm Matinee I I I Sat, December 8 8 pm I Seating preference: . I PLEASE SEND ME: I I I _ Regular Adult tickets at $9 ::..$ ___ _ Discount Student/Senior Citizen/Military/ ' I UHM Faculty-Staff at $7 "-$ ___ I I I I PROCESSING FEE (per order) $ 1.00 1. I • . October 26, 27, 31, and November TOTAL AMOUNT ENCLOSED $ I I I I will pay by : I 1, 2, 3, and 4, 1990 check (Made payable to the UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII) Alliance for Drama Education Credit card : Mastercard Visa :.:N:::.o.______ _ I I I I Benefit Performances Exp. -

Guest: Terence Knapp Lss 508 (Length: 26:46) First Air Date: 10/18/11

GUEST: TERENCE KNAPP LSS 508 (LENGTH: 26:46) FIRST AIR DATE: 10/18/11 My feet have always been a problem. Well, ever since I’ve been to the islands, that is. Oh, not when I was a boy in Belgium; no, I was as good on my feet as anybody in those days, running around the countryside, helping out on the farm, driving the cows in at night, skating on the River Dijle. Why, the night before I left home for good, I walked fourteen miles to say goodbye to my mother at the Shrine of Our Lady. Twelve years I promised her. This studio at PBS Hawaiʻi has been the scene of many wonderful productions. From music specials, educational and informational programs, to shows about the arts, our cameras have captured them all. But in 1976, over a series of several days, a high water mark in local television was set. Journey with us to that time, as we look back on the career of actor Terrence Knapp, here on Long Story Short. Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox is Hawaiʻi’s first weekly television program produced and broadcast in high definition. Aloha mai kākou. I’m Leslie Wilcox. In this edition of Long Story Short, you’ll meet a man who is considered by many to be a cultural treasure of Hawaiʻi, a devoted teacher of the dramatic arts, who chose to relocate from the British Isles of Shakespeare to an island home of a very different kind, an actor who has performed with Sir Laurence Olivier in the National Theater of Great Britain, and who mentored Booga Booga’s James Grant Benton. -

December2,3,4, 8,9, 10, 11 , 1977 Kennedy Theatre/ University of Hawaii the UNIVERSITY THEATRE Presents

December2,3,4, 8,9, 10, 11 , 1977 Kennedy Theatre/ University of Hawaii THE UNIVERSITY THEATRE presents by Kobo Abe Translated and directed by James R. Brandon Scene design by Howard Brewer Costume designs by Sandra Finney Lighting design and technical direction by Mark Boyd Sound by Robert Bethune Assistant director Kathryn Yashiki CAST: (in order of appearance) FUJINO, the animal keeper . ..... ... ............... .......... Dennis Nakano PROFESSOR .................................................... David Furumoto SON 'S WIFE . .. .... .. ... ................................ .. .......... Miki Kim PROFESSOR 'S SON ................. ... .... ..... .. ... .. .. .. Richard Williams MALE UEH ........... ... .. .. .... .. .. .......... ..... ....... ... Ralph Hirayama FEMALE UEH ....................................................... Mary Bishop FEMALE STUDENT ......... ............... ...... ......... Elizabeth Wichmann ASSIST ANT ........................................................ Barry Knapp MAID . .. .. .... .. ... .... ... .... ....... .... .. .............. Tina Marie Goff The play takes place in the professor's anima I spirit laboratory, Japan, 1977. ACT I Morning. A ten minute intermission ACT II Early morning, the following day. DIRECTOR'S NOTES Kobo Abe is said to be a great lover of science fiction. He also has been called a writer of detec tive stories. It is easy to see why, looking at our play tonight. The hero ofT HE ANIMAL HUNTER, the Professor, entertains a fantastic, pseudo-scientific belief in something called "animal spirit." In order to test the power of the animal-like Uehs to cure human illness, he sets up, in his laboratory dungeon, an elaborate spirit experiment (which you will have to sitthrough most of the play to see). He exhorts those around him to eatonlyfood "with the letter 'i' in the name," since, as we all know, spirit travels through the "eye." Did his father turn into a raven and fly off into the sky? The Pro fessor thinks it likely. -

Puritans, Missionaries, and Language Trouble in James Grant Benton's

Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance vol. 18 (33), 2018; DOI: 10.18778/2083-8530.18.05 ∗ Rhema Hokama Shakespeare in Hawai‘i: Puritans, Missionaries, and Language Trouble in James Grant Benton’s Twelf Nite O Wateva!, a Hawaiian Pidgin Translation of Twelfth Night1 Abstract: In 1974, the Honolulu-based director James Grant Benton wrote and staged Twelf Nite O Wateva!, a Hawaiian pidgin translation of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. In Benton’s translation, Malolio (Malvolio) strives to overcome his reliance on pidgin English in his efforts to ascend the Islands’ class hierarchy. In doing so, Malolio alters his native pidgin in order to sound more haole (white). Using historical models of Protestant identity and Shakespeare’s original text, Benton explores the relationship between pidgin language and social privilege in contemporary Hawai‘i. In the first part of this essay, I argue that Benton characterizes Malolio’s social aspirations against two historical moments of religious conflict and struggle: post-Reformation England and post-contact Hawai‘i. In particular, I show that Benton aligns historical caricatures of early modern puritans with cultural views of Protestant missionaries from New England who arrived in Hawai‘i beginning in the 1820s. In the essay’s second part, I demonstrate that Benton crafts Malolio’s pretentious pidgin by modeling it on Shakespeare’s own language. During his most ostentatious outbursts, Malolio’s lines consist of phrases extracted nearly verbatim from Shakespeare’s original play. In Twelf Nite, Shakespeare’s language becomes a model for speech that is inauthentic, affected, and above all, haole. Keywords: Twelfth Night, Reformation studies, puritanism, pidgin and creole languages. -

2011 October Graduation Programme

October 2011 The University of Waikato The Crest Ko Te Tangata The outside red border – a stylised The University’s motto, Ko Te Tangata/ fern frond or pitau – symbolises new For the People, refl ects our intrinsic belief birth, growth, vitality, strength and that people are central to the institution achievement. Inside the border is and are its most valued resource. the University’ss coat off arms. The open bookk surrounsurroundedded byy thee four stars of theheSo Southernuthern Cross is a symbol of learning.arning. TheThe crescrestt design is in thee UniUniversity’sversity’s colocoloursolouolours of black, red andnd ggold.old. WaiataWWaaiaata KoKo Te WhareW Wānanga o Waikato Ko Te Wharere WāWānanga o Waikato e tū nei ‘KoKo te TaTangata’ngaata’ te tohu TīhTīhei mauri ora!! Waikato te iwi; Waikato te awa; Taupiri te maunga; Tainui te waka. Ko Te WhWhareare Wānangananga o Waikato e tū nei Ko te tino kaupapa he hora māmātaurangaranga kki te ao. KŌKKŌKIRI! TheTh University U i off Waikato ThisTh s is the UnUniversityUniiverrsittyy of Waikato presentingti tot you ‘The People’ is the emblem Behold I live!! Waikato the people; Waikato the river Taupiri the sacred mountain; Tainui the canoe This is the University of Waikato presenting to you Its purpose, to spread enlightenment to the world. ONWARD!! Contents UNIVERSITY OFFICERS 2 WELCOME 3 CEREMONY SPEAKERS 4 ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS 5 HONORARY DOCTORATES 6 QUALIFICATIONS TO BE CONFERRED TE KOHINGA MĀRAMA MARAE » WEDNESDAY 19 OCTOBER 20110 1 – 9.30AM9.330AM 8 FOUNDERS MEMORIAL THEATRETRRE » THURSDAY 20 OCTOBER 2011 – 10AM0AM 12 » THURSDAY 20 OCTOBER 2011 – 22PMPM 21 » THURSDAY 20 OCTOBER 2011 – 55PMPM 28 HILLARY SCHOLARS 32 QUALIFICATIONS PREVIOUSLY CONFERRED/AWARDEDONFERRRED/AWARDED 334 UNIVERSITY OF WAIKATO ACADEMICDEMICC LEADERSLEAEADDERS 5151 SPEAKER PROFILES 54 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITYTY 55 OUR COMMITMENT 56 CEREMONIAL TRADITIONS 57 'GOD DEFEND NEWW ZEZEALAND'ALAND ANDD 'GAUDEAMUS'GAUD AMUS 588 HONORARY AWARDS 59 Due to the nature of the graduation ceremony it is often subject to last minute changes. -

Download This Issue

Ma¯lamalama 1 ma¯lamalamaTHE LIGHT OF KNOWLEDGE www.hawaii.edu/malamalama Editor Celebrating our centennial, and Hawai‘i’s best and brightest Cheryl Ernst 2007 is here—the year UH turns 100! As we celebrate the university’s centennial, Art Director Rowen Tabusa (BFA ’79 Ma¯noa) I am delighted also to celebrate the academic achievements of high-performing Photographer Hawai‘i high school graduates by announcing a Bob Chinn Centennial Scholars program that provides financial Associate Editor incentives to attend any of our UH campuses. The Tracy Matsushima (BA ’90 Ma¯noa) university is committed to strengthening undergraduate Online Editor Jeela Ongley (BA ’97 Ma¯noa) education by creating access to public higher education Contributing Alumni Editor in the state of Hawai‘i for our best and brightest students. Nico Schnitzler (BA ’03 Ma¯noa) At the same time, we need to ensure that our students University of Hawai‘i President succeed in their educational pursuits and graduate in a David McClain timely manner, and this is where financial aid can help. Board of Regents Beginning in fall 2007, incoming freshmen will receive a $1,000 scholarship Andres Albano Jr. (BS ’65, MBA ’72 Ma¯noa) if they score 1,800 or higher on the three-part SAT Reasoning Test (or the ACT Byron W. Bender equivalent) or graduate in spring 2007 or later with an unweighted 3.8 grade Michael A. Dahilig (BS ’03, JD ’06 Ma¯noa) point average. Students will continue to receive the grant for up to four years on Ramon de la Peña (MS ’64, a UH baccalaureate campus or two years at a UH community college, provided PhD ’67 Ma¯noa) they maintain a 3.0 grade point average. -

From the President of Aloha Airlines

scapI.:. to your own spec}al=jSlanll! On the beach, Princeville, Kauai. Put yourself in this picture. Kauai. A place of your own in Paradise. Just moments away from Honolulu-PaJi Ke Kua at Princeville. A home away from home. Or a permanent residence. A plantation atmosphere amid tropic foliage. Pali Ke Kua. What could compare with the joy of spending a weekend-or a week-or forever in such beautiful surroundings. You can right now. PaJi Ke Kua Increment /I is now available. Make your dreams come true. Talk to Mike McCormack Realtors. And put yourself in this picture. mike me carmack. Reallars A Division of The McCormack Land Company, Ltd. Executive offices and Honolulu sales division: Condominium offices: Suite 1212, Davies Pacific Center 4481 Rice Street Lihue, Kauai Phone 245-3991 841 Bishop Street, Honolulu 96801 Phone 537-3311 Princeville, Hanalei Phone 826-6120 Whalers Village, Kaanapali, Maui Phon e 661-3608 1HREAl TOR WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT OF ALOHA AIRLINES Dear Friends, As we approach the end of the year, we look back on 1973 as having MANUFACTURING & DISTRIBUT ION been very si9nifi cant for Aloha Ai rl ines and the people who have Kenneth B. Herndon supported us and worked so hard to brin9 success to our compa ny. Production Manage r David Plummer In 1973, we found ways to bet ter serve you, the inter-island traveler , Mfg . & Distr. Manager wit h new and improved servi ces and additional equipment. Last sprin g, Aloha Airlines added a si xt h Boeing 737 Funb ird to i ts fleet and offered mo re fl ights at more conven ient t imes than ever before. -

Footfalls Echo in the Memory

Verner C. Bickley, after the University of Cardiff and service in the Royal Navy in India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), joined the British Colonial Service and served as an Education Officer in Singapore before joining the British Council in Burma and Indonesia. He later returned to the Overseas Service as Director of the Hong Kong Government’s Institute of Language. He is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Hong Kong and Chairman of the English-Speaking Union, Hong Kong. FOOTFALLS ECHO IN THE MEMORY A Life with the Colonial Education Service and the British Council in Asia Verner C. Bickley The Radcliffe Press LONDON • NEW YORK To Gillian for her patience and love Supported by Hong Kong Arts Development Council fully supports freedom of artistic expression. The views and opinions expressed in this project do not represent the stand of the Council. Published in 2010 by Radcliffe Press An Imprint of I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Verner C. Bickley 2010 All illustrations © Verner C. Bickley 2010, except the photographs of the staff of Altrincham Grammar School and of the School Scout Hut The right of Verner C. Bickley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

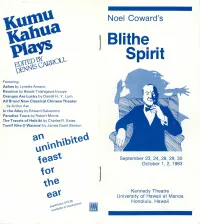

Blithe Spirit

Noel Coward's 1 Blithe · Spirit Featuring: Ashes by Lynette Amano Reunion by Bessie Toishigawa Inouye Oranges Are Lucky by Darrell H. Y . Lum All Brand New Classical Chinese Theater by Arthur Aw In the Alley by Edward Sakamoto Paradise Tours by Robert Morris The Travels of Heikiki by Charles R. Kates Twelf Nite 0 Wateva! by James Grant Benton an . """b\t.ed un'n''' ~east September 23, 24, 28, 29, 30 October 1, 2, 1983 ~ot ] the · Kennedy Theatre eat University of Hawaii at Manoa Honolulu, Hawaii The University Theatre Director's Notes presents Noel Pierce Coward (1899-1973) was a legend in his own lifetime. His song and playwriting began in 1918 just a few years after an extremely precocious adolescence. As a child actor his career was energetically promoted by a 'stage mother' every bit as determined as the matriarch portrayed ] by Ethel Merman in GYPSY. Processing from the Imperial Blithe Spirit Twilight of Victorian Empire through the last opulence of Edwardian profligacy Coward found himself as a very young by Noel Coward ) man scrambling for fame and fortune. During the era, now labelled as the Great Depression or The Jazz Age, Coward's Directed by Terence Knapp hedonistic companions included Talullah Bankhead, the Scene design by Richard G. Mason Prince of Wales and Wallis Simpson, the Mountbattens, and Costume design by Sandra Finney Alexander Woolcott. Lighting design by Noa Kristi It is difficult for the audiences of today to realise that in his early career Coward was regarded with angry spleen and vituperation. THE VORTEX (1924) and FALLEN ANGELS (1925) were regarded by middle-class reviewers of the time as thoroughly indecent and immoral because of the author's Characters (in order of appearance): lighthearted examination of such topics as drugs, drink and Edith . -

1990.Road to Tokyo.Pdf

JOURNEYS ... \rhe Road to ~okyo! THE SOVIET ACROBATIC REVUE MONDAY. JANUARY 7, 1991 7:30P.M. Blaisdell Concert Hall Dazzling gymnastic skills! Vaudevillian stage presence! Circus hijinks! All seats reserved: $20. $15. $10 Tickets on sale beginning December 17, November30 1990 at the Blaisdell Center box office. For information 521-2911. December 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, furl of a statewide tour arranged by the University of & Hawaii, CCECS under a grantfrom the State Foundation 13, 14, 15, 16 on Culture and the Arts. Presented in association with the HawaU Society for American-Soviet Friendship. 1990 The University of Hawaii at Manoa Department of Theatre and Dance in cooperation with the Music Department presents The Road to Tokyo! A New Kabuki Comedy Inspired by Jippensha Ikku's Shank's Mare (Tokai Dochu Hizakurige) A Sequel to The Road to Kyoto! by James R. Brandon and Kathy Foley Script by James R. Brandon and Brian Shaughnessy Directed by James R. Brandon Assisted by Lawrence D. Lessard Choreography by Onoe Kikunobu AMERICAN COLLEGE THEATER FESTIVAL XXIII PRESENTED AND PRODUCED BY THE Assisted by Onoe Kikunobukazu JOHN F. KENNEDY CENTER FOR THE and Onoe Kikunobuaki PERFORMING ARTS Musical Direction by Chie Yamada Supported in Part by Assisted by Ricardo D. Trimillos The Kennedy Center Corporate Fund Vocal Coaching by David Furumoto The U.S. Department of Education Scenic Design by Joseph D. Dodd Ryder System Costumes Coordinated by Sandra Finney This production is a Participating entry in the Lighting Design and Technical Direction American College Theater Festival (ACTF). The aims by Mark Boyd of this national educational theater program are to identify and promote quality in college-level theater TIME: Spring 1868, the first year of the modem Meiji era production. -

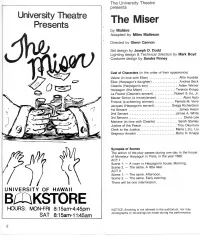

Bt.:I:\KSTORE HOURS: MON-FRI 8:15Am-4:45Pm NOTICE: Smoking Is Not Allowed in the Auditorium , Nor May Ph Otographs Or Recordings Be Made During the Performance

The University Theatre presents University Theatre The Miser Presents by Moliere Adapted by Miles Malleson Directed by Glenn Cannon Set design by Joseph D. Dodd Lighting design & Technical direction by Mark Boyd Costume design by Sandra Finney Cast of Characters (in the order of their appearance) Valere (in love with Elise) ..... ..... .. Alfie Huebler Elise (Harpagon's daughter) . ..... ...... .. Andrea Beck Cleante (Harpagon's son) .. ..... .... Adam Weiner Harpagon (the Miser) .... .. ....... .. ... Terence Knapp La Fleche (Cieante's servant) . .......... Robert S. Ito, Jr. Master Simon (a moneylender) . ... ... ..... Alani Apio Frosine (a scheming woman) ... ... .. .. Pamela M. VierCI Jacques (Harpagon's servant) .......... Gregg Richardson 1st Servant . .. ..... ....... .... .. .. ...... James Hearn 2nd Servant .. ...... .. .. ..... James A. White 3fd Servant . Diane Lee Mariane (in love with Cleante) .. ... .. .. Sarah Stanley / Justice of the Peace .... .... .. .. ... ... Troy Okumura Clerk to the Justice . .... ....... ..... Maria L.S.L. Liu Seigneur Anselm ... ......... ... .. ... Barry H. Knapp Synopsis of Scenes The action of the play passes during one day in the house of Monsieur Harpagon in Paris, in the year 1668. ACT I Scene 1. - A room in Harpagon's house. Morning. Scene 2. - The same. A little later. ACT II Scene 1. - The same. Afternoon. Scene 2. - The same. Early evening. There will be one intermission. UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII Bt.:I:\KSTORE HOURS: MON-FRI 8:15am-4:45pm NOTICE: Smoking is not allowed in the auditorium , nor may ph otographs or recordings be made during the performance. SAT 8: 15am-11 :45am 2 Director's Notes Set Designer's Notes Jean Bapti ste Poquelin (Moliere), 1622-1673, was an The scenic design process begins with a list of what 1 actor, director, producer, and playwright all at once . -

Ma11 at ~Pm 11 * Pre-Sho~ C.Hat at 1Pm Interpreted in Americ.An '5Ign Language

MAI NSTAGE 2004-2005 S EA SO N AP~YT£D ~Y !arne~ ~rant ~enton from ~ha~e~peare' s T'llt\fth Ni9ht or What You \'Ji\\ D£vi~£D ~D DIF£t:T£D ~v Tennu ~napp Apri\ ?..?.., ?-.'3~, ?..&, ?-.1, '30*' at &pm Ma11 at ~pm 11 * pre-sho~ c.hat at 1pm interpreted in Americ.an '5ign Language University of Hawai'i at Manoa Department of Theatre and Dance • College of Arts and Humanities Front of House Information For large print programs, assistive listening devices, or any other accessibility requests, please contact the House Manager or call the Kennedy Theatre Box Office at 956-7655 (voice/text). Please silence all pagers, phones and digital watches. No photog raphy or video recording is permitted. Please refrain from eating, drinking or smoking in the theatre. In following with University of Hawai'i policy, smoking is not permitted within 20 feet of the Kennedy Theatre building. Your as sistance in helping us adhere to this policy is greatly appreciated. The UHM ticket program is supported by a grant from the Stu dent Activity Fee and Program Board. DON'T MISS Shakespeare's Birthday Bash XXXV April 24, 6pm Free and Open to the Public WATEVA! director Terence Knapp celebrates the Bard's birthday with readings, songs and stories. A 35 year tradition! ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• NOW SHOWING Late Night at the Earle Ernst Lab Theatre Arabian Night By Roland Schimmelpfennig Directed by Peter Ruocco April 23, 29*, 30 at 11:00 p.m. April 24 at 8:00 p.m. *post-show rap follows Friday, April 29 performance Arabian Night takes place in an apartment complex on a hot sum mer night.