Battle of Midway Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ladies and Gentlemen

reaching the limits of their search area, ENS Reid and his navigator, ENS Swan decided to push their search a little farther. When he spotted small specks in the distance, he promptly radioed Midway: “Sighted main body. Bearing 262 distance 700.” PBYs could carry a crew of eight or nine and were powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-1830-92 radial air-cooled engines at 1,200 horsepower each. The aircraft was 104 feet wide wing tip to wing tip and 63 feet 10 inches long from nose to tail. Catalinas were patrol planes that were used to spot enemy submarines, ships, and planes, escorted convoys, served as patrol bombers and occasionally made air and sea rescues. Many PBYs were manufactured in San Diego, but Reid’s aircraft was built in Canada. “Strawberry 5” was found in dilapidated condition at an airport in South Africa, but was lovingly restored over a period of six years. It was actually flown back to San Diego halfway across the planet – no small task for a 70-year old aircraft with a top speed of 120 miles per hour. The plane had to meet FAA regulations and was inspected by an FAA official before it could fly into US airspace. Crew of the Strawberry 5 – National Archives Cover Artwork for the Program NOTES FROM THE ARTIST Unlike the action in the Atlantic where German submarines routinely targeted merchant convoys, the Japanese never targeted shipping in the Pacific. The Cover Artwork for the Veterans' Biographies American convoy system in the Pacific was used primarily during invasions where hundreds of merchant marine ships shuttled men, food, guns, This PBY Catalina (VPB-44) was flown by ENS Jack Reid with his ammunition, and other supplies across the Pacific. -

Two US Navy's Submarines

Now available to the public by subscription. See Page 63 Volume 2018 2nd Quarter American $6.00 Submariner Special Election Issue USS Thresher (SSN-593) America’s two nuclear boats on Eternal Patrol USS Scorpion (SSN-589) More information on page 20 Download your American Submariner Electronically - Same great magazine, available earlier. Send an E-mail to [email protected] requesting the change. ISBN List 978-0-9896015-0-4 American Submariner Page 2 - American Submariner Volume 2018 - Issue 2 Page 3 Table of Contents Page Number Article 3 Table of Contents, Deadlines for Submission 4 USSVI National Officers 6 Selected USSVI . Contacts and Committees AMERICAN 6 Veterans Affairs Service Officer 6 Message from the Chaplain SUBMARINER 7 District and Base News This Official Magazine of the United 7 (change of pace) John and Jim States Submarine Veterans Inc. is 8 USSVI Regions and Districts published quarterly by USSVI. 9 Why is a Ship Called a She? United States Submarine Veterans Inc. 9 Then and Now is a non-profit 501 (C) (19) corporation 10 More Base News in the State of Connecticut. 11 Does Anybody Know . 11 “How I See It” Message from the Editor National Editor 12 2017 Awards Selections Chuck Emmett 13 “A Guardian Angel with Dolphins” 7011 W. Risner Rd. 14 Letters to the Editor Glendale, AZ 85308 18 Shipmate Honored Posthumously . (623) 455-8999 20 Scorpion and Thresher - (Our “Nuclears” on EP) [email protected] 22 Change of Command Assistant Editor 23 . Our Brother 24 A Boat Sailor . 100-Year Life Bob Farris (315) 529-9756 26 Election 2018: Bios [email protected] 41 2018 OFFICIAL BALLOT 43 …Presence of a Higher Power Assoc. -

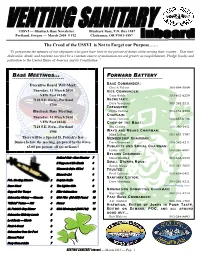

The Creed of the USSVI Is Not to Forget Our Purpose……

USSVI — Blueback Base Newsletter Blueback Base, P.O. Box 1887 Portland, Oregon — March 2010 # 192 Clackamas, OR 97015-1887 The Creed of the USSVI is Not to Forget our Purpose…… “To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments, Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its Constitution.” BASE MEETINGS... FORWARD BATTERY Executive Board Will Meet: BASE COMMANDER: Chuck Nelson 360-694-5069 Thursday, 11 March 2010 VICE COMMANDER: VFW Post #4248 Gary Webb 503-632-6259 7118 S.E. Fern—Portland SECRETARY: 1730 Dave Vrooman 503-262-8211 TREASURER: Blueback Base Meeting: Collie Collins 503-254-6750 CHAPLAIN: Thursday, 11 March 2010 Scott Duncan 503-667-0728 VFW Post #4248 CHIEF OF THE BOAT: 7118 S.E. Fern—Portland Stu Crosby 503-390-1451 1900 WAYS AND MEANS CHAIRMAN: Mike LaPan 503-655-7797 There will be a Special St. Patrick’s Day MEMBERSHIP CHAIRMAN: Dinner before the meeting, prepared by the wives. Dave Vrooman 503-262-8211 $5.00 per person, all are welcome! PUBLICITY AND SOCIAL CHAIRMAN: LeRoy Vick 503-367-6087 BYLAWS CHAIRMAN: Holland Club –New Member 7 Chris Stafford 503-632-4535 It Happened this Month 8 SMALL STORES BOSS: Sandy Musa 503-387-5055 Women in Subs OK’ed 8 TRUSTEE: Binnacle List 8 Fred Carneau 503-654-0451 SANITARY EDITOR: Feb. Meeting Minutes 2 Dolphin Raffle 8 Dave Vrooman 503-262-8211 Dues Chart 2 The Lighter Side 9 [email protected] NOMINATION COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN: Support Our Troops 3 Killer Submarines 10 Ray Lough 360-573-4274 Submarine History — Mascots 3 USS Flier (SS-250) Found 10 PAST BASE COMMANDER: J.D. -

Gato Class Boats Finished the War with a Mod 3A Fairwater

A VISUAL GUIDE TO THE U.S. FLEET SUBMARINES PART ONE: GATO CLASS (WITH A TAMBOR/GAR CLASS POSTSCRIPT) 1941-1945 (3rd Edition, 2019) BY DAVID L. JOHNSTON © 2019 The Gato class submarines of the United States Navy in World War II proved to be the leading weapon in the strategic war against the Japanese merchant marine and were also a solid leg of the triad that included their surface and air brethren in the USN’s tactical efforts to destroy the Imperial Japanese Navy. Because of this they have achieved iconic status in the minds of historians. Ironically though, the advancing years since the war, the changing generations, and fading memories of the men that sailed them have led to a situation where photographs, an essential part of understanding history, have gone misidentified which in some cases have led historians to make egregious errors in their texts. A cursory review of photographs of the U.S. fleet submarines of World War II often leaves you with the impression that the boats were nearly identical in appearance. Indeed, the fleet boats from the Porpoise class all the way to the late war Tench class were all similar enough in appearance that it is easy to see how this impression is justified. However, a more detailed examination of the boats will reveal a bewildering array of differences, some of them quite distinct, that allows the separation of the boats into their respective classes. Ironically, the rapidly changing configuration of the boats’ appearances often makes it difficult to get down to a specific boat identification. -

HR.10240 Nvg118covuk

OSPREY New Vanguard PUBLISHING US Submarines 1941–45 Jim Christley • Illustrated by Tony Bryan © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com New Vanguard • 118 US Submarines 1941–45 Jim Christley • Illustrated by Tony Bryan © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US SUBMARINES 1941–45 INTRODUCTION he shooting portion of World War II burst on the American Navy early on a Sunday morning in December 1941, with the Japanese Tattack on Pearl Harbor. On that morning the face of naval warfare in the Pacific changed utterly. No longer would the war at sea be decided by squadrons of the world’s largest and most powerful battleships. Instead, the strategic emphasis shifted to a combination of two more lethal and far-ranging naval weapon systems. The aircraft carrier would replace the battleship by being able to increase the deadly range of a fleet from a few tens of miles – the range of battleship guns – to the hundreds of miles range of bomb- and torpedo-carrying aircraft. In addition, the American submarine would be able to place a strangler’s grip on the throat of the Japanese empire that, unlike the German U-boats’ attempts to control the Atlantic waters, could not be broken. Some have said that the result of the attack at Pearl Harbor was fortuitous in that it forced the US Navy to look toward the carrier and submarine to defend the southern Pacific and the United States’ western coast. This argument overlooks, however, the prewar build-up in those two weapons platforms, which seems to indicate that some individuals were looking seriously toward the future and the inevitable conflict. -

Of Deaths in Service of Royal Naval Medical, Dental, Queen Alexandra's Royal Naval Nursing Service and Sick Berth Staff

Index of Deaths in Service of Royal Naval Medical, Dental, Queen Alexandra’s Royal Naval Nursing Service and Sick Berth Staff World War II Researched and collated by Eric C Birbeck MVO and Peter J Derby - Haslar Heritage Group. Ranks and Rate abbreviations can be found at the end of this document Name Rank / Off No 1 Date Ship, (Pennant No), Type, Reason for loss and other comrades lost and Rate burial / memorial details (where known). Abel CA SBA SR8625 02/10/1942 HMS Tamar. Hong Kong Naval Base. Drowned, POW (along with many other medical shipmates) onboard SS Lisbon Maru sunk by US Submarine Grouper. 2 Panel 71, Column 2, Plymouth Naval Memorial, Devon, UK. 1 Officers’ official numbers are not shown as they were not recorded on the original documents researched. Where found, notes on awards and medals have been added. 2 Lisbon Maru was a Japanese freighter which was used as a troopship and prisoner-of-war transport between China and Japan. When she was sunk by USS Grouper (SS- 214) on 1 October 1942, she was carrying, in addition to Japanese Army personnel, almost 2,000 British prisoners of war captured after the fall of Hong Kong in December Name Rank / Off No 1 Date Ship, (Pennant No), Type, Reason for loss and other comrades lost and Rate burial / memorial details (where known). Abraham J LSBA M54850 11/03/1942 HMS Naiad (93). Dido-class destroyer. Sunk by U-565 south of Crete. Panel 71, Column 2, Plymouth Naval Memorial, Devon, UK. Abrahams TH LSBA M49905 26/02/1942 HMS Sultan. -

Major Fleet-Versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Second Edition Milan Vego Milan Vego Second Ed

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Historical Monographs Special Collections 2016 HM 22: Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific arW , 1941–1945 Milan Vego Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-historical-monographs Recommended Citation Vego, Milan, "HM 22: Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific arW , 1941–1945" (2016). Historical Monographs. 22. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-historical-monographs/22 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Monographs by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 War, Pacific the in Operations Fleet-versus-Fleet Major Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Second Edition Milan Vego Milan Vego Milan Second Ed. Second Also by Milan Vego COVER Units of the 1st Marine Division in LVT Assault Craft Pass the Battleship USS North Carolina off Okinawa, 1 April 1945, by the prolific maritime artist John Hamilton (1919–93). Used courtesy of the Navy Art Collection, Washington, D.C.; the painting is currently on loan to the Naval War College Museum. In the inset image and title page, Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance ashore on Kwajalein in February 1944, immediately after the seizure of the island, with Admiral Chester W. -

Military History Anniversaries 1 Thru 31 Oct

Military History Anniversaries 1 thru 31 Oct Events in History over the next 30 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Oct 00 1943 – WW2: USS Dorado (SS–248) – Date of sinking unknown. Most likely either accidently bombed and sunk by friendly Guantanamo–based flying boat on 13 October or sunk by a German submarine mine in the West Indies. 77 killed Oct 01 1880 – John Philip Sousa becomes leader of the United States Marine Band. Oct 01 1942 – WW2: USS Grouper torpedoes Lisbon Maru not knowing she is carrying 1800 British POWs from Hong Kong. Over 800 died in the sinking. Oct 01 1942 – WW2: First flight of the first American jet fighter aircraft Bell XP–59 'Airacomet'. The USAF was not impressed by its performance and cancelled the contract when fewer than half of the aircraft ordered had been produced Oct 01 1943 – WW2: Naples falls to Allied soldiers. Oct 01 1947 – F-86 Sabre – The transonic jet fighter aircraft flies for the first time. Oct 01 1951 – 24th Infantry Regiment, last all–black military unit, deactivated. Oct 01 1957 – Cold War: B–52 bombers begin full–time flying alert in case of USSR attack. Oct 01 1979 – The United States returns sovereignty of the Panama Canal to Panama. Oct 01 1992 – U.S. aircraft carrier Saratoga cripples Turkish destroyer TCG Muavenet (DM–357) causing 27 deaths and injuries by negligently launched missiles. Oct 02 1780 – American Revolution: John André, British Army officer of the American Revolutionary War, is hanged as a spy by American forces. -

UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER August 2013

OUR CREED: To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments. Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its constitution. UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER August 2013 1 Lost Boats / Crew Listing 3 Picture of the Month 14 Members 15 Honorary Members 15 CO’s Stateroom 16 XO’S Stateroom 17 Meeting Attendees 18 Minutes 18 Old Business 18 New Business 19 Good of the Order 20 Base Contacts 21 Birthdays 21 Welcome 21 Binnacle List 21 Quote of the Month 21 Word of the Month 21 Member Profile of the Month 22 Traditions of the Naval Service 25 Dates in U.S. Naval History 26 Dates in U.S. Submarine History 32 Submarine Memorials 47 Monthly Calendar 51 Submarine Trivia 52 Submarine Veterans Gulf Coast 2013 Annual Christmas Party Flyer 53 Advertising Partners 54 2 USS Bullhead (SS-332) Lost on: Lost on August 6, 1945 with the loss of 84 crew members in the Lombok Strait while on her 3rd war patrol when sunk by a depth charge dropped by 8/6/1945 a Japanese Army p lane. Bullhead was the last submarine lost during WWII. NavSource.org US Navy Official Photo Class: SS 285 Commissioned: 12/4/1944 Launched: 7/16/1944 Builder: Electric Boat Co (General Dynamics) Length: 312 , Beam: 27 #Officers: 10 , #Enlisted: 71 Fate: U. S. and British submarines operating in the vicinity were unable to NavSource.org contact Bullhead and it was presumed that she was sunk during Japanese antisubmarine attacks. -

Venting Sanitary Inboard

VENTING SANITARY INBOARD Issue 258, January 2016 OUR CREED: FORWARD BATTERY “To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates BASE COMMANDER who gave their lives in George Hudson pursuit of their duties 503.843.2082 while serving their [email protected] country. That their dedication, deeds, and VICE COMMANDER supreme sacrifice be a Jay Agler constant source of 503.771.1774 motivation toward greater accomplishments. SECRETARY Pledge loyalty and Dennis Smith patriotism to the United 503.981.4051 States of America and its Constitution.” TREASURER Mike Worden 503.708.8714 COMMANDER’S LOG CHAPLAIN/NOMINATION COMMITTEE CHAIR Scott Duncan Recapping December, I would like to mention our Christmas Party and 503.667.0728 the Wreaths Across America ceremony. We had a great turn out at our CHIEF OF THE BOAT annual Christmas Party. Sixty-one people showed up, a few more than Arlo Gatchel last year, and we raised $630.00 in our silent auction. Attendees gave 503.771.0540 very positive feedback on the meal and banquet staff. Vice WAYS & MEANS CHAIR Commander Jay Agler did an outstanding job working with the hotel Vacant staff for a great meal and setting up the banquet room. I want to thank Bill Bryan and Shelia Alfonso for all their work in setting up and MEMBERSHIP CHAIR/SMALL STORES BOSS running the silent auction. Also, thanks to the Blueback Base crew Dave Vrooman members who donated gifts and memorabilia for the auction. We had 503.466.0379 a great party! PUBLICITY & SOCIAL CHAIR Gary Schultz, Jr. At the Christmas party we 503.666.6125 also swore in our newly BYLAWS CHAIR/PAST BASE elected base officers, COMMANDER Secretary Dennis Smith and Ray Lough 360.573.4274 Treasurer Mike Worden. -

Rising to Victory, Part 1

by Edward C. Whitman Previous UNDERSEA WARFARE articles on U.S. submarines in the Pacific during World War II have focused largely on individual “submarine heroes” and their extraordinary war records. In contrast, the present two-part article attempts to step back and view the Pacific submarine campaign from a theater perspective that illuminates both its wartime context and the evolution of a top-level strategy. Part I: Retreat and Retrenchment Strategic Background Since the era of the Spanish-American War, when the United States first assumed territorial responsibilities in the western Pacific, contingency plans had been prepared to deal with the possibility of war with Japan. Known as the “Orange” series in their many revisions, these war plans all assumed that the Japanese would initiate hostilities against the United States with an attack on the Philippine Islands. In response, the U.S. Asiatic Fleet and the in-country Army garrisons would be taskedwith fighting a delaying action there until the U.S. Pacific Fleet could arrive from the West Coast to defeat the Japanese Navy in a classic Mahanian sea battle. In the late-1930s, with Japanese aggression in East Asia an increasing threat, the Orange Plan – by then named “Rainbow Five” – loomed ever larger in the Navy’s strategic thinking. Consequently, just before the opening of World War II in Europe, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Pacific Fleet to shift its operating bases from the West Coast to Pearl Harbor. Simultaneously, the Asiatic Fleet – consisting nominally of a small surface force and a handful of antiquated submarines – was reinforced by transferring several newer submarine divisions to the Philippines from San Diego and Hawaii. -

The Evacuation of British Women and Children from Hong Kong to Australia in 1940

The Evacuation of British Women and Children from Hong Kong to Australia in 1940 Tony Banham A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA November 2014 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v Abbreviations and Acronyms......................................................................................vii Preliminaries...................................................................................................................... x Introduction.....................................................................................................................xiv Chapter 1. Planning ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Fear and Legislation............................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Hong Kong’s Evacuation Scheme Plan in Context .................................................. 13 1.3 The Colony Before Evacuation...................................................................................... 28 1.4 The Order to Evacuate..................................................................................................... 38 Chapter 2. Evacuation .................................................................................................44 2.1 Avoiding and Evading Evacuation ..............................................................................