Rising to Victory, Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ladies and Gentlemen

reaching the limits of their search area, ENS Reid and his navigator, ENS Swan decided to push their search a little farther. When he spotted small specks in the distance, he promptly radioed Midway: “Sighted main body. Bearing 262 distance 700.” PBYs could carry a crew of eight or nine and were powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-1830-92 radial air-cooled engines at 1,200 horsepower each. The aircraft was 104 feet wide wing tip to wing tip and 63 feet 10 inches long from nose to tail. Catalinas were patrol planes that were used to spot enemy submarines, ships, and planes, escorted convoys, served as patrol bombers and occasionally made air and sea rescues. Many PBYs were manufactured in San Diego, but Reid’s aircraft was built in Canada. “Strawberry 5” was found in dilapidated condition at an airport in South Africa, but was lovingly restored over a period of six years. It was actually flown back to San Diego halfway across the planet – no small task for a 70-year old aircraft with a top speed of 120 miles per hour. The plane had to meet FAA regulations and was inspected by an FAA official before it could fly into US airspace. Crew of the Strawberry 5 – National Archives Cover Artwork for the Program NOTES FROM THE ARTIST Unlike the action in the Atlantic where German submarines routinely targeted merchant convoys, the Japanese never targeted shipping in the Pacific. The Cover Artwork for the Veterans' Biographies American convoy system in the Pacific was used primarily during invasions where hundreds of merchant marine ships shuttled men, food, guns, This PBY Catalina (VPB-44) was flown by ENS Jack Reid with his ammunition, and other supplies across the Pacific. -

November 2010 Perch Base, USSVI Volume 16 - Issue 11 Phoenix, Arizona

THE MONTHLY NEWSLEttER OF November 2010 PERCH BASE, USSVI Volume 16 - Issue 11 PHOENIX, ARIZONA What’s “Below Decks” in the HE REED GuiDES OUR EFFORts AS ERCH ASE MidWatch T USSVI C P B . ITEM Page # SEE THE NEXT PAGE FOR THE FULL TEXT OF OUR CREED. Full Text of the: 2 USSVI Creed Perch Base Foundation 3 Support Members Base Officers - Sailing 4 Orders Annual Veterans Day Pa- 5 rade Announcement Our Generous Sponsors 6 October 2010 - Perch Base 7 Meeting Minutes “From the Wardroom” 10 Base Commander’s mes- sage A Message from the Mem- 10 bership Chairman Chaplain’s Column 11 Binnacle List 12 Perch Base November 13 LEST WE FORGET THOSE STIll ON PATROL Birthdays What’s New Online 13 NOVEMBER ETERNAL PATROLS Shipmate-to-Shipmate 14 This Ain’t No S**t USS CORVINA (SS-226) 4 Nov 1943 82 Lost Perch Base “Octoberfest” 15 Japanese Submarine Attack off Truk “A Thank-you Note . .” 16 USS ALBACORE (SS-218) 07 Nov 1944 86 Lost Holland Club Members 17 Boats Selected for First Possible Japanese Mine between Honshu and Hokkaido, Japan 19 Female Submariners USS GROWLER (SS-215) 08 Nov 1944 85 Lost Lost Boat: 20 USS Scamp (SS-277) Possible Japanese Surface Attack in South China Sea Russian Navy’s Rocket 23 USS SCAMP (SS-277) 11 Nov 1944 83 Lost Torpedo Mailing Page 20 Japanese Surface Attack in Tokyo Bay area NEXT REGULAR MEETING USS SCULPIN (SS-191) 19 Nov 1943 12 Lost (51 POWS) 12 noon, Saturday, Nov. 13, 2010 Japanese Surface Attack off Truk American Legion Post #105 3534 W. -

USSVI Thresher Base News

USSVI Thresher Base News November 2010 September 2010 Minutes The September meeting of Thresher the Southern Maine Veterans’ Cem- which is quite impressive - 3 double Base was held at Newick’s Restaurant etery, Springvale, ME on August 24. hangers. He said that 3 hours was not in Dover, NH on Saturday, September •Sub Sailor of the Year, Groton Base - enough time. There is a guided tour 18. The meeting was called to order The base has received thank you notes that takes you through the on base followed by a silent prayer and pledge from all 3 of the sailors. They were hanger that houses 4 Airforce Ones: of allegiance. The Tolling of the Bells very appreciative. Kennedy, Roosevelt (2), Truman. was conducted for those boats lost •The base received a letter and $50 • Peter Joy brought up for discussion in September and October. A silent donation from Jack Hunter for the obtaining a non-descript memorial for prayer was said for those on eternal Thresher Memorial Service. The do- all submarine veterans for the South- patrol. nation was made in honor of Irv Searl. ern Maine Veterans Cemetery. He A sound off of those present was •Peter Joy made a suggestion to ask has been in touch with Tom Conlon conducted - There were 14 members Vice Admiral Emery to speak at the at national. Before making any further and 4 spouses. Secretary’s Report - Thresher Memorial Service. contacts, a sponsor is needed to collect Minutes from the July 2010 meeting and maintain the funds until all mon- were read and approved. -

Members of the USNA Class of 1963 Who Served in the Vietnam War

Members of the USNA Class of 1963 Who Served in the Vietnam War. Compiled by Stephen Coester '63 Supplement to the List of Over Three Hundred Classmates Who Served in Vietnam 1 Phil Adams I was on the USS Boston, Guided Missile Cruiser patrolling the Vietnam Coast in '67, and we got hit above the water line in the bow by a sidewinder missile by our own Air Force. ------------------- Ross Anderson [From Ross’s Deceased Data, USNA63.org]: Upon graduation from the Academy on 5 June 1963, Ross reported for flight training at Pensacola Naval Air Station (NAS) which he completed at the top of his flight class (and often "Student of the Month") in 1964. He then left for his first Southeast Asia Cruise to begin conducting combat missions in Vietnam. Landing on his newly assigned carrier USS Coral Sea (CVA-43) at midnight, by 5 am that morning he was off on his first combat mission. That squadron, VF-154 (the Black Knights) had already lost half of its cadre of pilots. Ross' flying buddy Don Camp describes how Ross would seek out flying opportunities: Upon our return on Oct 31, 1965 to NAS Miramar, the squadron transitioned from the F-8D (Crusader) to the F4B (Phantom II). We left on a second combat cruise and returned about Jan 1967. In March or April of 1967, Ross got himself assigned TAD [temporary additional duty] to NAS North Island as a maintenance test pilot. I found out and jumped on that deal. We flew most all versions of the F8 and the F4 as they came out of overhaul. -

Gato Rulebook

Introduction ..................................................2 Post-Combat Resolution Phase ................24 Game Components ......................................2 Refit Segment ............................................26 Set-Up ..........................................................8 Campaign Outcome ..................................27 Sequence of Play ......................................10 Optional Rules ............................................27 Strategic Segment......................................11 Historical Descriptions................................28 Operations Segment ..................................13 Credits ........................................................29 Tactical Segment........................................15 Example Turn..............................................30 Combat Resolution Phase..........................17 Quick Reference ........................................33 Setting Sun INTRODUCTION Submarine operations from Pearl Harbor during 1944 and 1945. Gato Leader places you in command of a squadron of American Submarines in the Pacific Ocean during Each Campaign Sheet has Set-Up information for the World War II. Campaign. The Campaign Map is made up of several Areas showing the ports, transit areas, and Patrol The four Campaigns represent different periods during Areas used by American Submarines during the time World War II. You’ll play each Campaign using one of period covered by the Campaign. three durations: Short, Medium, or Long. Campaign Map Areas As the squadron commander, -

The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF THE ATOMIC BOMB: A SUBMERGED CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT OF THE SUNKEN FLEET OF OPERATION CROSSROADS AT BIKINI AND KWAJALEIN ATOLL LAGOONS REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS Prepared for: The Kili/Bikini/Ejit Local Government Council By: James P. Delgado Daniel J. Lenihan (Principal Investigator) Larry E. Murphy Illustrations by: Larry V. Nordby Jerry L. Livingston Submerged Cultural Resources Unit National Maritime Initiative United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers Number 37 Santa Fe, New Mexico 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS ... LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ......................................... 111 FOREWORD ................................................... vii Secretary of the Interior. Manuel Lujan. Jr . ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................... ix CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ........................................ 1 Daniel J. Lenihan Project Mandate and Background .................................. 1 Methodology ............................................... 4 Activities ................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: Operation Crossroads .................................. 11 James P. Delgado The Concept of a Naval Test Evolves ............................... 14 Preparing for the Tests ........................................ 18 The AbleTest .............................................. 23 The Baker Test ............................................. 27 Decontamination Efforts ....................................... -

Gato Class Boats Finished the War with a Mod 3A Fairwater

A VISUAL GUIDE TO THE U.S. FLEET SUBMARINES PART ONE: GATO CLASS (WITH A TAMBOR/GAR CLASS POSTSCRIPT) 1941-1945 (3rd Edition, 2019) BY DAVID L. JOHNSTON © 2019 The Gato class submarines of the United States Navy in World War II proved to be the leading weapon in the strategic war against the Japanese merchant marine and were also a solid leg of the triad that included their surface and air brethren in the USN’s tactical efforts to destroy the Imperial Japanese Navy. Because of this they have achieved iconic status in the minds of historians. Ironically though, the advancing years since the war, the changing generations, and fading memories of the men that sailed them have led to a situation where photographs, an essential part of understanding history, have gone misidentified which in some cases have led historians to make egregious errors in their texts. A cursory review of photographs of the U.S. fleet submarines of World War II often leaves you with the impression that the boats were nearly identical in appearance. Indeed, the fleet boats from the Porpoise class all the way to the late war Tench class were all similar enough in appearance that it is easy to see how this impression is justified. However, a more detailed examination of the boats will reveal a bewildering array of differences, some of them quite distinct, that allows the separation of the boats into their respective classes. Ironically, the rapidly changing configuration of the boats’ appearances often makes it difficult to get down to a specific boat identification. -

Newtarget Submarine List

Target Submarines List from Bill Buckley TM 1950-1956 This is dedicated to those boats that gave the last final extra measure for us in weapons tests. S(T) Sunk as target from "US Submarines Through 1945" by Norman Friedman. Jim Christley did research in other places and kindly allowed its use here. Also comments have been added by sailors that rode the boat that sank them or have knowledge of the sinking. SS-2 A-1 was target. Sold for scrapping 26 Jan 22 with USS Puritan. SS-3 A-2 Adder 16-Jan-22 1/26/1922 Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-4 A-3 Grampus Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-5 A-4 Moccasin 16-Jan-22 Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-6 A-5 Pike 16-Jan-22 Sunk by explosion 15 Apr 17 Salvaged Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-7 A-6 Porpoise 16-Jan-22 Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-8 A-7 Shark 16-Jan-22 Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-9 C-1 Octopus Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-10 B-1 Viper 16-Jan-22 Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-11 B-2 Cuttlefish 17-Jan-22 Used as target. Hulk sunk in Manila Bay, near Corregidor SS-12 B-3 Tarantula 17-Jan-22 Used as target. -

HR.10240 Nvg118covuk

OSPREY New Vanguard PUBLISHING US Submarines 1941–45 Jim Christley • Illustrated by Tony Bryan © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com New Vanguard • 118 US Submarines 1941–45 Jim Christley • Illustrated by Tony Bryan © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US SUBMARINES 1941–45 INTRODUCTION he shooting portion of World War II burst on the American Navy early on a Sunday morning in December 1941, with the Japanese Tattack on Pearl Harbor. On that morning the face of naval warfare in the Pacific changed utterly. No longer would the war at sea be decided by squadrons of the world’s largest and most powerful battleships. Instead, the strategic emphasis shifted to a combination of two more lethal and far-ranging naval weapon systems. The aircraft carrier would replace the battleship by being able to increase the deadly range of a fleet from a few tens of miles – the range of battleship guns – to the hundreds of miles range of bomb- and torpedo-carrying aircraft. In addition, the American submarine would be able to place a strangler’s grip on the throat of the Japanese empire that, unlike the German U-boats’ attempts to control the Atlantic waters, could not be broken. Some have said that the result of the attack at Pearl Harbor was fortuitous in that it forced the US Navy to look toward the carrier and submarine to defend the southern Pacific and the United States’ western coast. This argument overlooks, however, the prewar build-up in those two weapons platforms, which seems to indicate that some individuals were looking seriously toward the future and the inevitable conflict. -

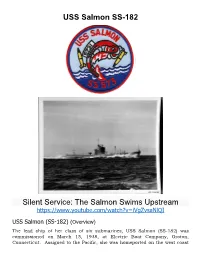

USS Salmon SS-182 Silent Service: the Salmon Swims Upstream

USS Salmon SS-182 Silent Service: The Salmon Swims Upstream https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iVgZvsaNlQI USS Salmon (SS-182) (Overview) The lead ship of her class of six submarines, USS Salmon (SS-182) was commissioned on March 15, 1938, at Electric Boat Company, Groton, Connecticut. Assigned to the Pacific, she was homeported on the west coast until transferred to the Philippines, where she was serving during the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Relocating to Australia, Salmon patrolled the East Indies, South China Sea, Indochina, and the Philippines, sinking three ships. Following an overhaul on the U.S. west coast, she patrolled off Japan, sinking an additional ship in the summer of 1943. Operating as part of a "wolf-pack" against Japanese shipping in September 1944, Salmon was damaged during a depth-charge attack. Despite her damage, she surfaced, engaged the enemy, and drove them off. This action earned the submarine a Presidential Unit Citation. Due her age and service, she transited back to the Atlantic in February 1945 and spent the rest of the war in overhaul and trained sailors. Decommissioned on September 24, 1945, Salmon was scrapped in April 1946. A model of Salmon can be found In Harm's Way (Pacific Section) at the National Museum of the U.S. Navy. USS Salmon (SS-182) was the lead ship of her class of submarine. She was the second ship of the United States Navy to be named for the salmon, a soft-finned, game fish which inhabits the coasts of America and Europe in northern latitudes and ascends rivers for the purpose of spawning. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF THE ATOMIC BOMB: A Submerged Cultural Resources Assessment of the Sunken Fleet of Operation Crossroads at Bikini and Kwajalein Atoll Lagoons U.S. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE SUBMERGED CULTURAL RESOURCES UNIT NATIONAL MARITIME INITIATIVE THE ARCHEOLOGY OF THE ATOMIC BOMB: A SUBMERGED CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT OF THE SUNKEN FLEET OF OPERATION CROSSROADS AT BIKINI AND KWAJALEIN ATOLL LAGOONS REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS Prepared for: The Kili/Bikini/Ejit Local Government Councii By: James P. Delgado Daniel J. Lenihan (Principal Investigator) Larry E. Murphy Illustrations by: Larry V. Nordby Jerry L. Livingston Submerged Cultural Resources Unit National Maritime Initiative United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers Number 37 Santa Fe, New Mexico 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS ... LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . 111 FOREWORD . vii Secretary of the Interior, Manuel Lujan, Jr. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . ix CHAPTER ONE: Introduction . 1 Daniel J. Lenihan —.. .—. Yroject Mandate and Background . 1 Methodology . 4 Activities . 7 CHAPTER TWO: Operation Crossroads . 11 James P. Delgado The Concept ofa Naval Test Evolves, . 14 Preparing for the Tests . 18 The Able Test . ., . ...,,, . 23 The Baker Test . 27 Decontamination Efforts . 29 The Legacy of Crossroads . 31 The 1947 Scientific Resurvey . 34 CHAPTER THREE: Ship’s Histories for the Sunken Vessels . 43 James P. Delgado USS Saratoga . 43 USS Arkansas . 52 HIJMSNagato . 55 HIJMSSakawa . 59 USSPrinzEugen . 60 USS Anderson . 64 USS Larson . 66 USSApogon . 70 USS Pilotfish . 72 USSGilliam . 73 USS Carlisle . 74 ARDC-13 . 76 YO-160 . 76 LCT-414, 812, 1114, 1175, and1237 . 77 CHAPTER FOUR: Site Descriptions . 85 James P. Delgado and LarryE.