Stefan Wolle, and Ilko-Sasha Kowalczuk Is Equally Glaring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Reimagining

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Kreibich, Stefanie Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR: Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Stefanie Kreibich Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Modern Languages Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures April 2018 Abstract In the last decade, everyday life in the GDR has undergone a mnemonic reappraisal following the Fortschreibung der Gedenkstättenkonzeption des Bundes in 2008. No longer a source of unreflective nostalgia for reactionaries, it is now being represented as a more nuanced entity that reflects the complexities of socialist society. The black and white narratives that shaped cultural memory of the GDR during the first fifteen years after the Wende have largely been replaced by more complicated tones of grey. -

Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’S Window to the World Under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989

Tomasz Blusiewicz Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’s Window to the World under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989 Draft: Please do not cite Dear colleagues, Thank you for your interest in my dissertation chapter. Please see my dissertation outline to get a sense of how it is going to fit within the larger project, which also includes Poland and the Soviet Union, if you're curious. This is of course early work in progress. I apologize in advance for the chapter's messy character, sloppy editing, typos, errors, provisional footnotes, etc,. Still, I hope I've managed to reanimate my prose to an edible condition. I am looking forward to hearing your thoughts. Tomasz I. Introduction Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, a Stasi Oberst in besonderen Einsatz , a colonel in special capacity, passed away on June 21, 2015. He was 83 years old. Schalck -- as he was usually called by his subordinates -- spent most of the last quarter-century in an insulated Bavarian mountain retreat, his career being all over three weeks after the fall of the Wall. But his death did not pass unnoticed. All major German evening TV news services marked his death, most with a few minutes of extended commentary. The most popular one, Tagesschau , painted a picture of his life in colors appropriately dark for one of the most influential and enigmatic figures of the Honecker regime. True, Mielke or Honecker usually had the last word, yet Schalck's aura of power appears unparalleled precisely because the strings he pulled remained almost always behind the scenes. "One never saw his face at the time. -

Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Revised Pages Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic Heather L. Gumbert The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © by Heather L. Gumbert 2014 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (be- yond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2017 2016 2015 2014 5 4 3 2 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978– 0- 472– 11919– 6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978– 0- 472– 12002– 4 (e- book) Revised Pages For my parents Revised Pages Revised Pages Contents Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Cold War Signals: Television Technology in the GDR 14 2 Inventing Television Programming in the GDR 36 3 The Revolution Wasn’t Televised: Political Discipline Confronts Live Television in 1956 60 4 Mediating the Berlin Wall: Television in August 1961 81 5 Coercion and Consent in Television Broadcasting: The Consequences of August 1961 105 6 Reaching Consensus on Television 135 Conclusion 158 Notes 165 Bibliography 217 Index 231 Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This work is the product of more years than I would like to admit. -

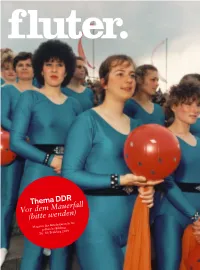

Thema DDR Vor Dem Mauerfall (Bitte Wenden)

Thema DDR Vor dem Mauerfall (bitte wenden) Magazin der Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Nr. 30 / Frühling 2009 Was nicht in Alle bpb-Produkte unter www.bpb.de EDITORIAL INHALT diesem Heft steht, steht woanders Die DDR war einmal. »Sich dumm zu stellen, war eine Form von Und zwar hier: Sachbücher, Für viele ist es ein Land, das sie nur aus Erzählungen Opposition« . Seite 4 kennen. Aus diesem Block historischen Materials, Zuckerbrot und Peitsche: Der Historiker Stefan Romane, Broschüren, Filme der durch die Entfernung oft etwas Märchenhaf- Wolle über den Alltag in der DDR und den sprung- & Links zum Thema tes bekommt, hat fluter einige Geschichten heraus- haften Umgang der Regierung mit dem Volk gegriffen. Bei aller Komplexität – es gibt ein paar einfache Wahrheiten: Ein Staat, der seine Bürger Ein Stück Karibik . Seite 10 einsperrt und ermordet, wenn sie fliehen wollen, Es wäre ja auch zu schön gewesen: Die Geschichte ist kein guter Staat. Ein politisches System, das ei- von einer DDR-Insel brachte Wind in die Köpfe ner kleinen Gruppe alter Männer unkontrollierte Macht über alles gibt, ist eine Diktatur. Auch wenn Lost in Music . Seite 11 Stefan Wolle: Werner Bräunig: ONLINE: Die heile Welt der Diktatur Rummelplatz sie sich den Namen »Demokratische Republik« Völlig aus dem Takt: Nichts haben die Machthaber Stefan Wolle gelingt es, die widersprüchlichen Bilder Nach dem Vorabdruck einiger Kapitel fiel Bräunig, Auf der Seite »Deine Geschichte«können Jugend- gibt. Diktaturen sind im besten Fall absurd und in so gefürchtet wie Jugendbewegungen. Rock, Beat einer unter gegangenen Welt zusammenzufügen. der schreibende Bergmann, bei der SED in Ungnade. -

Behind the Berlin Wall.Pdf

BEHIND THE BERLIN WALL This page intentionally left blank Behind the Berlin Wall East Germany and the Frontiers of Power PATRICK MAJOR 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York Patrick Major 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Major, Patrick. -

Bulletin 10-Final Cover

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN 10 61 “This Is Not A Politburo, But A Madhouse”1 The Post-Stalin Succession Struggle, Soviet Deutschlandpolitik and the SED: New Evidence from Russian, German, and Hungarian Archives Introduced and annotated by Christian F. Ostermann I. ince the opening of the former Communist bloc East German relations as Ulbricht seemed to have used the archives it has become evident that the crisis in East uprising to turn weakness into strength. On the height of S Germany in the spring and summer of 1953 was one the crisis in East Berlin, for reasons that are not yet of the key moments in the history of the Cold War. The entirely clear, the Soviet leadership committed itself to the East German Communist regime was much closer to the political survival of Ulbricht and his East German state. brink of collapse, the popular revolt much more wide- Unlike his fellow Stalinist leader, Hungary’s Matyas spread and prolonged, the resentment of SED leader Rakosi, who was quickly demoted when he embraced the Walter Ulbricht by the East German population much more New Course less enthusiastically than expected, Ulbricht, intense than many in the West had come to believe.2 The equally unenthusiastic and stubborn — and with one foot uprising also had profound, long-term effects on the over the brink —somehow managed to regain support in internal and international development of the GDR. By Moscow. The commitment to his survival would in due renouncing the industrial norm increase that had sparked course become costly for the Soviets who were faced with the demonstrations and riots, regime and labor had found Ulbricht’s ever increasing, ever more aggressive demands an uneasy, implicit compromise that production could rise for economic and political support. -

Tailoring Truтʜ

Tailoring Truth Studies in Contemporary European History Editors: Konrad Jarausch, Lurcy Professor of European Civilization, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and a Director of the Zentrum für Zeithistorische Studien, Potsdam, Germany Henry Rousso, Senior Fellow at the Institut d’historie du temps present (Centre national de la recherché scientifi que, Paris) and co-founder of the European network “EURHISTXX” Volume 1 Volume 9 Between Utopia and Disillusionment: A Social Policy in the Smaller European Union Narrative of the Political Transformation States in Eastern Europe Edited by Gary B. Cohen, Ben W. Ansell, Robert Henri Vogt Henry Cox, and Jane Gingrich Volume 2 Volume 10 The Inverted Mirror: Mythologizing the A State of Peace in Europe: West Germany Enemy in France and Germany, 1898–1914 and the CSCE, 1966–1975 Michael E. Nolan Petri Hakkarainen Volume 3 Volume 11 Confl icted Memories: Europeanizing Visions of the End of the Cold War Contemporary Histories Edited by Frederic Bozo, Marie-Pierre Rey, Edited by Konrad H. Jarausch and Thomas N. Piers Ludlow, and Bernd Rother Lindenberger with the Collaboration of Annelie Volume 12 Ramsbrock Investigating Srebrenica: Institutions, Facts, Volume 4 Responsibilities Playing Politics with History: The Edited by Isabelle Delpla, Xavier Bougarel, and Bundestag Inquiries into East Germany Jean-Louis Fournel Andrew H. Beatt ie Volume 13 Volume 5 Samizdat, Tamizdat, and Beyond: Alsace to the Alsatians? Visions and Transnational Media During and Aft er Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, -

The Stasi at Home and Abroad the Stasi at Home and Abroad Domestic Order and Foreign Intelligence

Bulletin of the GHI | Supplement 9 the GHI | Supplement of Bulletin Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Supplement 9 (2014) The Stasi at Home and Abroad Stasi The The Stasi at Home and Abroad Domestic Order and Foreign Intelligence Edited by Uwe Spiekermann 1607 NEW HAMPSHIRE AVE NW WWW.GHI-DC.ORG WASHINGTON DC 20009 USA [email protected] Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Washington DC Editor: Richard F. Wetzell Supplement 9 Supplement Editor: Patricia C. Sutcliffe The Bulletin appears twice and the Supplement usually once a year; all are available free of charge and online at our website www.ghi-dc.org. To sign up for a subscription or to report an address change, please contact Ms. Susanne Fabricius at [email protected]. For general inquiries, please send an e-mail to [email protected]. German Historical Institute 1607 New Hampshire Ave NW Washington DC 20009-2562 Phone: (202) 387-3377 Fax: (202) 483-3430 Disclaimer: The views and conclusions presented in the papers published here are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent the position of the German Historical Institute. © German Historical Institute 2014 All rights reserved ISSN 1048-9134 Cover: People storming the headquarters of the Ministry for National Security in Berlin-Lichtenfelde on January 15, 1990, to prevent any further destruction of the Stasi fi les then in progress. The poster on the wall forms an acrostic poem of the word Stasi, characterizing the activities of the organization as Schlagen (hitting), Treten (kicking), Abhören (monitoring), -

Introduction: the Historian As a Detective

Notes Introduction: The Historian as a Detective 1. In preparation of the two-part “docu-drama” titled Deutschlandspiel (German Game) to mark the tenth anniversary of the reunification of Germany, along with other broadcasters the Zweite Deutsche Fernsehen (ZDF) had had around 60 interviews conducted with the international main actors in the process. I took part in these. Deutschlandspiel was produced by Ulrich Lenze, and Hans- Christoph Blumenberg was the director. Blumenberg conducted a largest num- ber of the interviews, while Thomas Schuhbauer and I conducted a smaller number. I also wrote the treatment and served as an academic advisor for the film project. 2. Compare the literature at the end of this book. 3. The official files of Gorbachev’s talks with other politicians are in the Presidential Archive. Those in the Gorbachev Foundation in Moscow that I was able to look at were prepared at the time by clerks and translators. Most were countersigned by Chernayev himself, the main “note-taker” then. These meeting minutes stand apart under the comparisons that I carried out and appear, among others, to be authentic, because critical statements or sections are included, in which Gorbachev does not appear in the best light. Nor have I found any “retrospective foreshadowing” of particular views of Gorbachev or his discussion partners. The Politburo minutes are not official minutes, but rather later compilations of the notes made during the meetings by Medvedev, Skhakhnazarov, who has died, and Chernayev—that is, by Gorbachev’s people. These Politburo minutes also give a credible impression, particularly naturally in their original note form. -

The East German Revolution of 1989

The East German Revolution of 1989 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Ph.D. in the Faculty of Economic and Social Studies. Gareth Dale, Department of Government, September 1999. Contents List of Tables 3 Declaration and Copyright 5 Abstract 6 Abbreviations, Acronyms, Glossary and ‘Who’s Who’ 8 Preface 12 1. Introduction 18 2. Capitalism and the States-system 21 (i) Competition and Exploitation 22 (ii) Capitalism and States 28 (iii) The Modern World 42 (iv) Political Crisis and Conflict 61 3. Expansion and Crisis of the Soviet-type Economies 71 4. East Germany: 1945 to 1975 110 5. 1975 to June 1989: Cracks Beneath the Surface 147 (i) Profitability Decline 147 (ii) Between a Rock and a Hard Place 159 (iii) Crisis of Confidence 177 (iv) Terminal Crisis: 1987-9 190 6. Scenting Opportunity, Mobilizing Protest 215 7. The Wende and the Fall of the Wall 272 8. Conclusion 313 Bibliography 322 2 List of Tables Table 2.1 Government spending as percentage of GDP; DMEs 50 Table 3.1 Consumer goods branches, USSR 75 Table 3.2 Producer and consumer goods sectors, GDR 75 Table 3.3 World industrial and trade growth 91 Table 3.4 Trade in manufactures as proportion of world output 91 Table 3.5 Foreign trade growth of USSR and six European STEs 99 Table 3.6 Joint ventures 99 Table 3.7 Net debt of USSR and six European STEs 100 Table 4.1 Crises, GDR, 1949-88 127 Table 4.2 Economic crisis, 1960-2 130 Table 4.3 East Germans’ faith in socialism 140 Table 4.4 Trade with DMEs 143 Table 5.1 Rate of accumulation 148 Table 5.2 National -

New Research on East Germany Issue 8-1 May 21, 2017 Revue D’Études Interculturelles De L’Image Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies

REVUE D’ÉTUDES INTERCULTURELLES DE L’IMAGE JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL IMAGE STUDIES NEW RESEARCH ON EAST GERMANY ISSUE 8-1 MAY 21, 2017 REVUE D’ÉTUDES INTERCULTURELLES DE L’IMAGE JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL IMAGE STUDIES NEW RESARCH ON EAST GERMANY ISSUE 8-1 MAY 21, 2017 NEW RESEARCH ON EAST GERMANY ISSUE 8-1, 2017 Sommaire/Contents Guest Editor – Marc Silberman http://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.GDR.8-1 Issue Managing Editors - Brent Ryan Bellamy and Carrie Smith Editor in Chief | Rédacteur en chef Previous Team Members | Anciens membres de l’équipe Research Articles Sheena Wilson Marine Gheno, Dennis Kilfoy, Daniel Laforest, Lars Richter, Managing Editor | Rédacteur Katherine Rollans, Angela Sacher, Dalbir Sehmby, Justin Sully New Research on East Germany: An Introduction • 4 Brent Ryan Bellamy Marc Silberman Editorial Team | Comité de rédaction Negotiating Memories of Everyday Life during the Wende • 8 Maria Hetzer Brent Ryan Bellamy, Dominique Laurent, Andriko Lozowy, Editorial Advisory Board | Comité scientifique Tara Milbrandt, Carrie Smith-Prei, and Sheena Wilson Hester Baer, University of Maryland College Park, United States Beyond Domination: Socialism, Everyday Life in East German Housing Settlements, and New Directions in GDR Historiography • 34 Mieke Bal, University of Amsterdam & Royal Netherlands Academy Elicitations Reviews Editor | Comptes rendus critiques – Élicitations Eli Rubin of Arts and Sciences, Netherlands Tara Milbrandt Adventures in Communism: Counterculture and Camp in East Berlin • 48 Andrew Burke, University of Winnipeg, Canada Jake P. Smith Ollivier Dyens, Concordia University, Canada Archives for the Future:Thomas Heise’s Visual Archeology • 64 Web Editor | Mise en forme web Michèle Garneau, Université de Montréal, Canada Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann Brent Ryan Bellamy Wlad Godzich, University of California Santa Cruz, United States Whose East German Art is This? The Politics OF Reception After 1989 • 78 French Translator & Copy Editor | Traductions françaises Kosta Gouliamos, European University, Cyprus April A. -

Press Kit Nineties Berlin KALASCHNIKOW

Welcome to the nineties! Dear Sir or Madam, Welcome to nineties berlin! The following press kit will equip you with all essential information and is an invitation: Get an impression of the multimedia exhibition, talk with the creators, be curious, ask us questions. We are happily your contacts for interviews with the curators and managing directors. Sincerely, Melanie Alperstaedt Dr. Sabine Fatunz Telephone: +49 30 54 90 82 431 Email: [email protected] Table of contents: 2 Numbers and facts 4 Place: The Alte Münze 6 Guide bot 7 Exhibition: What is nineties berlin about? 9 Historical context 10 Structure of the exhibition and curator quotes 17 Contemporary witnesses: “Berlin Heads“ 19 Design of “Lost Berlin“ Numbers and facts Address: nineties berlin, Alte Münze, Molkenmarkt 2, 10179 Berlin-Mitte Duration: August 4, 2018 - February 28, 2019 Opening hours: Monday through Sunday, 10 a.m. - 8 p.m. No day off Ticket prices: At the door Adults: 12.50 € Reduced: 8.50 € (children aged 6 and older, schoolchildren, students, apprentices, recipients of unemployment benefit ALG- 2, severely disabled persons) Children younger than 6: free of charge Online Adults: 11.25 € Reduced: 7.65 € (children aged 6 and older, schoolchildren, students, apprentices, recipients of unemployment benefit ALG- 2, severely disabled persons) Children younger than 6: free of charge Groups of 10 or more people: 7.90 € per ticket School groups of 10 or more people: 5.90 € per ticket Website: www.nineties.berlin Social Media: " https://www.instagram.com/ninetiesberlin/ & https://www.facebook.com/ninetiesberlin! & https://twitter.com/ninetiesberlin! Operator:# DDR Kultur UG, Karl-Liebknecht-Str.