2020 Al-Abri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrations Cycle Tour Sunaysilah Fort New Era of CSR

Autumn, 2015 Autumn, Al Ghanjah Celebrations Cycle Tour Sunaysilah Fort New Era of CSR Printed on recycled paper We continue to engage with the community, and to see and respect human gifts in all their forms. Foreword by the For those less fortunate, we reserve 1.5% of NIAT, Chief Executive Officer distributed under our innovative and expanding Oman LNG Development Foudation (ODF). For the fortunately employed, we offer training, work openings, amenities to boost or ease production. For the less fortunate, logistical support in the form of equipment or mobility aids. Moderated growth, supported by education, training, maximised potential of human and material resources. The core values that drive our company and country’s success are inextricably entwined. I hope you enjoy reading this interesting edition of your magazine! Harib Al Kitani In this 45th year of Oman’s Modern Renaissance, we Chief Executive Officer have indeed much to celebrate, both nationally and here at Oman LNG. We have the good fortune to have HM Sultan Qaboos bin Said, a leader who launched one of the most successful Renaissance of the CONTENTS modern age, back home in good health. Our company has emerged stronger than ever from challenging times in the oil and gas market, at least Company News 2 in the pricing market. Welcome Back Your Majesty 6 Even more important to us at Oman LNG than the pricing market is the value of human life, and Oman Cycle Tour 10 we continue to uphold our safety record and to Sunaysilah Fort: A Historical Landmark 14 communicate the importance of safety through our staff, contractors, customers and to audiences Oman LNG Development Foundation: far beyond the company gates. -

Oman Tourist Guide SULTANATE of Discover the Secret of Arabia

Sultanate of Oman Tourist Guide SULTANATE OF Discover the secret of Arabia CONTENTS Sultanate 01 WELCOME // 5 of Oman 02 MUSCAT // 7 03 THE DESERT AND NIZWA // 13 04 ARABIAN RIVIERA ON THE INDIAN OCEAN // 19 05 WADIS AND THE MOUNTAIN OF SUN // 27 06 NATURE, HIKING AND ADVENTURE // 33 07 CULTURE OF OMAN // 39 08 INFORMATION // 45 Welcome 01 AHLAN! Welcome to Oman! As-salaamu alaykum, and welcome to the Head out of the city, and Oman becomes All of this, as well as a colourful annual enchanting Sultanate of Oman. Safe and even more captivating. Explore the small events calendar and a wide range of inviting, Oman will hypnotise you with towns nestled between the mountains. international sports events, ensures its fragrant ancient souks, mesmerise Visit the Bedouin villages. Drive the a travel experience unlike any other. with dramatic landscapes and leave incense route. You’ll do it all under the you spellbound with its stories. Home constant gaze of ancient forts dotted A journey of discovery awaits you in to numerous UNESCO World Heritage throughout the landscape like imposing this welcoming land at the crossroads Sites, Oman is steeped in history and sand castles. between Asia, Africa and Western has inspired some of literature’s most civilisation. Enjoy all of the marvels of famous tales. Stop by the date farms and witness the this unique setting, the ideal gateway harvesting of the roses, that cover the hills to Southern Arabia. Muscat, the vibrant capital, is full of with delicate hues of pink and fill the air memorable sites and experiences. -

Arabic IV Curriculum

Arabic IV Curriculum Grades 9-12: Unit Four Title: Arabian Peninsula: Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait and UAE 1 | P a g e U N I T 4 Course Description Philosophy Paterson Public Schools is committed to seeing that all students progress and develop the required skills to support second language acquisition. At the completion of a strong series of course studies, students will be able to: Possess knowledge of adequate vocabulary structured in contextual thematic units Express thoughts and ideas on a variety of topics Move progressively from simple sentence structures to a more complex use of verbs, adjectives, adverbs, richer expressions, etc.… Rely on background knowledge to develop fluency in the second language acquisition related to their daily lives, families, and communities Compose short dialogues, stories, narratives, and essays on a variety of topics Learn and embrace the culture and traditions of the native speakers’ countries while learning the language and cultural expressions Read, listen, and understand age-appropriate authentic materials presented by natives for natives, as well as familiar materials translated from English into the target language Become valuable citizens globally, understanding and respecting cultural differences, and promoting acceptance of all people from all cultures Overview The Arabic Program at Paterson Public Schools will focus on acquiring communication skills and cultural exposure. It is guided by the NJ DOE Model Curriculum for World Languages and encompasses the N.J.C.C.C. -

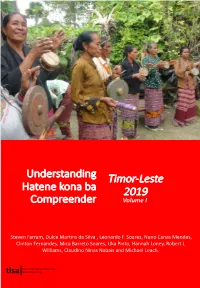

Understanding Hatene Kona Ba Compreender Timor-Leste 2019

Understanding Timor-Leste Hatene kona ba 2019 Compreender Volume I Steven Farram, Dulce Martins da Silva , Leonardo F. Soares, Nuno Canas Mendes, Clinton Fernandes, Mica Barreto Soares, Uka Pinto, Hannah Loney, Robert L Williams, Claudino Ninas Nabais and Michael Leach. Timor-Leste Studies Association tlsa www.tlstudies.org Hatene kona ba Timor-Leste 2019 Compreender Timor-Leste 2019 Understanding Timor-Leste 2019 Volume I 1 Proceedings of the Understanding Timor-Leste 2019 Conference, Liceu Campus, Universidade Nacional Timor- Lorosa’e (UNTL), Avenida Cidade de Lisboa, Dili, Timor-Leste, 27-28 June 2019. Edited by Steven Farram, Dulce Martins da Silva, Leonardo F. Soares, Nuno Canas Mendes, Clinton Fernandes, Mica Barreto Soares, Uka Pinto, Hannah Loney, Robert L Williams, Claudino Ninas Nabais and Michael Leach (eds). This collection first published in 2020 by the Timor-Leste Studies Association (www.tlstudies.org). Printed by Swinburne University of Technology. Copyright © 2020 by Steven Farram, Dulce Martins da Silva, Leonardo F. Soares, Nuno Canas Mendes, Clinton Fernandes, Mica Barreto Soares, Uka Pinto, Hannah Loney, Robert L Williams, Claudino Ninas Nabais, Michael Leach and contributors. All papers published in this collection have been peer refereed. All rights reserved. Any reproductions, in whole or in part of this publication must be clearly attributed to the original publication and authors. Cover photo courtesy of Lisa Palmer. Design and book layout by Susana Barnes. ISBN: 978-1-925761-26-9 (3 volumes, PDF format) 2 Contents – Volume 1 Lia Maklokek – Prefácio – Foreword 6 Lia Maklokek – CNC 8 Foreword – CNC 9 Dedication – Dr James Scambary 10 The Timor-Leste Studies Association 2005-2020: An Expanding Global Network 11 of Scholarship and Solidarity Clinton Fernandes, Michael Leach and Hannah Loney Hatene kona ba Timor-Leste 2019 17 1. -

Oman, Iran, and the United States: an Analysis of Omani Foreign Policy and Its Role As an Intermediary

Oman, Iran, and the United States: An Analysis of Omani Foreign Policy and Its Role as an Intermediary The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37736781 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! ! Oman, Iran, and the United States: An Analysis of Omani Foreign Policy and Its Role as an Intermediary Mohra Al Zubair A Thesis in the Field of Middle Eastern Studies for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2017 ! ! ! ! 2017 Mohra Al Zubair ! ! ! Abstract In a world where power is equivalent to water for the thirsty, foreign policy plays a key role in every country’s strength. Today, the Middle East is a battleground for several struggles for power, with civil unrest, sectarian divisions, and proxy wars found throughout the region. In this volatile area, foreign policy has the potential to protect a country from regional political vulnerability. But for such policy to work best, internal affairs must be prepared in order to serve well. One country that has succeeded notably in maintaining a balanced foreign policy, even amid complex regional situations, is the Sultanate of Oman. This thesis analyzes Oman’s foreign policy under the reign of Sultan Qaboos. It examines Oman’s positions on regional events that led to creating Oman’s favorable reputation for dealing with and mediating between sides, most notably between Iran and the United States. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 49 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2010 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group Windrush House Avenue Two Station Lane Witney OX28 4XW 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice8President Air 2arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KC3 C3E AFC Committee Chairman Air 7ice82arshal N 3 3aldwin C3 C3E 7ice8Chairman -roup Captain 9 D Heron O3E Secretary -roup Captain K 9 Dearman FRAeS 2embership Secretary Dr 9ack Dunham PhD CPsychol A2RAeS Treasurer 9 3oyes TD CA 2embers Air Commodore - R Pitchfork 23E 3A FRAes ,in Commander C Cummin s :9 S Cox Esq 3A 2A :A72 P Dye O3E 3Sc(En ) CEn AC-I 2RAeS :-roup Captain 2 I Hart 2A 2A 2Phil RAF :,in Commander C Hunter 22DS RAF Editor & Publications ,in Commander C - 9efford 23E 3A 2ana er :Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS THE PRE8,AR DE7E.OP2ENT OF DO2INION AIR 7 FORCES by Sebastian Cox ANS,ERIN- THE @O.D COUNTRABSB CA.. by , Cdr 11 Colin Cummin s ‘REPEAT, PLEASE!’ PO.ES AND CCECHOS.O7AKS IN 35 THE 3ATT.E OF 3RITAIN by Peter Devitt A..IES AT ,ARE THE RAF AND THE ,ESTERN 51 EUROPEAN AIR FORCES, 1940845 by Stuart Hadaway 2ORNIN- G&A 76 INTERNATIONA. -

Oman – the Islamic Democratic Tradition

Oman – The Islamic Democratic Tradition Oman is the inheritor of a unique political tradition, the imama (imamate), and has a special place in the Arab Islamic world. From the eighth century and for more than a thousand years, the story of Oman was essentially a story of an original, minority, movement, the Ibadi. This long period was marked by the search for a just imama through the Ibadi model of the Islamic State. The imama system was based on two principles: the free election of the imam leader and the rigorous application of shura (consultation). Thus, the imama system, through its rich experience, has provided us with the only example of an Arab-Islamic democracy. Hussein Ghubash’s well-researched book takes the reader on a historical voyage through geography, politics and culture of the region, from the sixteenth century to the present day. Oman has long-standing ties with East Africa as well as Europe; the first contact between Oman and European imperialist powers took place at the dawn of the 1500s with the arrival of the Portuguese, eventually followed by the Dutch, French and British. Persuasive, thorough and drawing on Western as well as Islamic political theory, this book analyses the different historical and geopolitical roles of this strategic country. Thanks to its millennial tradition, Oman enjoys a solid national culture and stable socio-political situation. Dr Ghubash is the author of several books and the U.A.E. ambassador to UNESCO. He holds a PhD in political science from Nanterre University, Paris X. Durham Modern -

The Omani Architectural Heritage -Identity and Continuity S.M

The Omani Architectural Heritage -Identity and Continuity S.M. Hegazy Scientific College of Design HERITAGE 2010- HERITAGE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT, Green Lines Institute, Portugal, V.2 P.1341: 1451 ABSTRACT: The Omani society is one of the few societies all over the world which is still keen to its national identity. Unprecedented in the gulf region, the contemporary buildings have order lines and respect for traditional heritage. This paper aims to recognize this distinguished ex- perience to maintain sustainability between the Omani heritage & contemporary vernacular architecture. A summary concerning the origins of Omani architecture will be presented. ABSTRACT:Then the identity as one of he important features of Omani society, culture, and architecture will be clarified. The preservation of Omani heritage as a reference will be demonstrated, followed by an example of a contemporary vernacular architectural project. The results and analysis of a questionnaire concerning the Omanis' level of satisfaction of contemporary ar- chitecture will be discussed. The research methodology depends on collecting data through references, field studies, a questionnaire and interviews. Data analysis has been conducted. 1THE ORIGINS OF OMANI ARCHITECTURE The material culture of Oman is too rich and varied to be dealt with in an exhaustive manner. In order to understand a culture; one has to look at the integration between history and art history- including architecture-together. Omani architecture is a series of complementary elements which have accumulated through the ages to create a coherent and harmonies built environment. Early Omani history and civili- zation can be seen from the perspective of the ancient history of the Near East and Gulf region. -

G - S C/50/5 ORIGINAL: English/Français/Deutsch/Español DATE/DATUM/FECHA: 2016-10-26

E - F - G - S C/50/5 ORIGINAL: English/français/deutsch/Español DATE/DATUM/FECHA: 2016-10-26 INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR UNION INTERNATIONALE INTERNATIONALER VERBAND UNIÓN INTERNACIONAL PARA THE PROTECTION OF NEW POUR LA PROTECTION ZUM SCHUTZ VON LA PROTECCIÓN DE LAS VARIETIES OF PLANTS DES OBTENTIONS VÉGÉTALES PFLANZENZÜCHTUNGEN OBTENCIONES VEGETALES Geneva Genève Genf Ginebra COUNCIL CONSEIL DER RAT CONSEJO Fiftieth Cinquantième Fünfzigste Quincuagésima Ordinary Session session ordinaire ordentliche Tagung sesión ordinaria Geneva, October 28, 2016 Genève, 28 octobre 2016 Genf, 28. Oktober 2016 Ginebra, 28 de octubre de 2016 COOPERATION IN EXAMINATION Document prepared by the Office of the Union Disclaimer: this document does not represent UPOV policies or guidance COOPÉRATION EN MATIÈRE D’EXAMEN Document établi par le Bureau de l’Union Avertissement : le présent document ne représente pas les principes ou les orientations de l’UPOV ZUSAMMENARBEIT BEI DER PRÜFUNG Vom Verbandsbüro ausgearbeitetes Dokument Haftungsausschluß: dieses Dokument gibt nicht die Grundsätze oder eine Anleitung der UPOV wieder COOPERACIÓN EN MATERIA DE EXAMEN Documento preparado por la Oficina de la Unión Descargo de responsabilidad: el presente documento no constituye un documento de política u orientación de la UPOV C/50/5 page 2 / Seite 2 / página 2 This document contains a synopsis of offers for cooperation in examination made by authorities, of cooperation already established between authorities and of any envisaged cooperation. * * * * * Le présent document contient un tableau synoptique des offres de coopération en matière d’examen faites par les services compétents, de la coopération déjà établie entre des services et de la coopération prévue. * * * * * Dieses Dokument enthält einen Überblick über Angebote für eine Zusammenarbeit bei der Prüfung, die von Behörden abgegeben worden sind, über Fälle einer bereits verwirklichten Zusammenarbeit zwischen Behörden und über Fälle, in denen eine solche Zusammenarbeit beabsichtigt ist. -

Issue-1 June - July 2019 Delhi 100 World Cultural Review Title Code: DELENG19688 About Us

Vol-1; Issue-1 June - July 2019 Delhi www.worldcultureforum.org.in 100 WORLD CULTURAL REVIEW Title Code: DELENG19688 ABOUT US World Culture Forum is an International organization who initiates peace-building and engages in extensive research on contemporary cultural trends across the globe. We firmly believe that peace can be attained through dialogue, discussion and even just listening. In this spirit, we honor the individuals and groups who are engaged in building peace. Striving to establish a boundless global filmmaking network, we invite everyone to learn about and appreciate authentic local cultures and the value of cultural diversity in film. Keeping in line with our Mission, we create festivals and conferences along with extensively researched papers to cheer creative thought and innovation in the field of culture as our belief lies in the idea – "Culture bounds Humanity" and any step towards it is a step towards a secure future. VISION We envisage the creation of a world which rests on the fundamentals of connected and harmonious co-existence which create a platform for connecting culture and perseverance to build solidarity by inter-cultural interactions. MISSION We are committed to providing a free, fair and equal platform to all cultures so as to build a relationship of mutual trust, respect, and cooperation which can achieve harmony and understand different cultures by inter-culture interactions and effective communication. 2 World Cultural Review June-July 2019 Delhi www.worldcultureforum.org.in Title Code: DELENG19688 World Cultural Review CONTENTS Vol-1; Issue-1, June-july 2019 100 Editor Prahlad Narayan Singh [email protected] Executive Editor Ankush Bharadwaj [email protected] Managing Editor Shiva Kumar [email protected] Associate Ankit Roy [email protected] Legal Adviser SERVING CULTURE AND HUMANITY 6 Dr. -

{DOWNLOAD} Oman, UAE & Arabian Peninsula Ebook

OMAN, UAE & ARABIAN PENINSULA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lonely Planet,Jenny Walker,Anthony Ham,Andrea Schulte-Peevers | 480 pages | 04 Oct 2016 | Lonely Planet Global Limited | 9781786571045 | English | Dublin 8, Ireland Arabian Peninsula - Wikipedia Iraq occupies an area of about , square miles and a 36 mile-long coastline on the Persian Gulf. Jordan is an autonomous Arab nation which is on the eastern bank of river Jordan in Western Asia. Jordan has a small coastline with the Red Sea while the Dead Sea is on its western boundary. It is on the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Amman is the cultural, political and economic center of the country. Jordan occupies an area of about 34, square miles and has a population of over 10 milion people. Kuwait shares a border with Saudi Arabia and Iraq. The country has over 4. Oil reserves were discovered in Iraq annexed Kuwait in Oman is an independent Arab state which is on the southeastern parts of Arabia in Asia. It is an Islamic state which has a strategically crucial position at the Persian Gulf. Oman shares a maritime boundary with Pakistan and Iran. Oman occupies an area of about , square miles and has over 4. A significant percentage of their economy depends on the trade of dates, numerous agricultural produces and fish, and tourism. Oman has the twenty-fifth largest oil reserves on earth. Qatar is an independent nation which is in the Qatar peninsula. Qatar is on the northeastern parts of Arabia and occupies an area of about 4, square miles. Its only land boundary is with Saudi Arabia while the Persian Gulf engulfs the rest of the state. -

THE DHOFAR CAMPAIGN 1970-1976 S

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 12, Nr 4, 1982. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za VICTORY IN HADES: THE FORGOTTEN WARS OF THE OMAN 1957-1959 and 1970-1976 PART 2: THE DHOFAR CAMPAIGN 1970-1976 s. Monick* Section A west), a number of important contrasts emerge in a comparison between the two campaigns. First, the underlying pressures impelling the in- surgent forces were of a different nature. In the Similarities and contrasts first war, the paramount factor underlying the During the years 1970-1976 Oman was once insurrection was traditional tribal seperatism (ad- again a theatre of operations in which the Sul- mittedly with the active support of Saudi Arabia tan's forces, supported by pro-Western powers, and Egypt), compounded by the deep rooted succeeded in defeating the insurgent forces friction between religious authority (vested in the seeking to destroy the established power struc- Imam) and secular power (embodied in the Sul- ture of Oman. In many respects, the political tan). configuration of this second war bore many 1 close resemblances to the first . One had, as in However, in the latter conflict, the paramount the first campaign of 1957 -1959, the active mili- influence in the insurgency was Communist sub- tary participation of Britain; in terms of both lead- version (manifested in the insurgent movement ership and the active involvement of British units designated the Popular Front for the Liberation of (including the Special Air Service Regiment - Oman, or PFLO); functioning as an extension of SAS - who, as in the first Omani campaign, were the power of a neighbouring Marxist state (The to playa major role in the war).