16P13.11 Microduplications FTNW.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Epidemiology

Received: 10 May 2019 | Revised: 31 July 2019 | Accepted: 28 August 2019 DOI: 10.1002/gepi.22260 RESEARCH ARTICLE Population‐wide copy number variation calling using variant call format files from 6,898 individuals Grace Png1,2,3 | Daniel Suveges1,4 | Young‐Chan Park1,2 | Klaudia Walter1 | Kousik Kundu1 | Ioanna Ntalla5 | Emmanouil Tsafantakis6 | Maria Karaleftheri7 | George Dedoussis8 | Eleftheria Zeggini1,3* | Arthur Gilly1,3,9* 1Wellcome Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, United Abstract Kingdom Copy number variants (CNVs) play an important role in a number of human 2Department of Medical Genetics, diseases, but the accurate calling of CNVs remains challenging. Most current University of Cambridge, Cambridge, approaches to CNV detection use raw read alignments, which are computationally United Kingdom intensive to process. We use a regression tree‐based approach to call germline CNVs 3Institute of Translational Genomics, Helmholtz Zentrum München—German from whole‐genome sequencing (WGS, >18x) variant call sets in 6,898 samples Research Center for Environmental across four European cohorts, and describe a rich large variation landscape Health, Neuherberg, Germany comprising 1,320 CNVs. Eighty‐one percent of detected events have been previously 4European Bioinformatics Institute, ‐ ‐ Wellcome Genome Campus, Hinxton, reported in the Database of Genomic Variants. Twenty three percent of high quality United Kingdom deletions affect entire genes, and we recapitulate known events such as the GSTM1 5William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and RHD gene deletions. We test for association between the detected deletions and and The London School of Medicine and 275 protein levels in 1,457 individuals to assess the potential clinical impact of the Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom detected CNVs. -

Identification of the Binding Partners for Hspb2 and Cryab Reveals

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-12-12 Identification of the Binding arP tners for HspB2 and CryAB Reveals Myofibril and Mitochondrial Protein Interactions and Non- Redundant Roles for Small Heat Shock Proteins Kelsey Murphey Langston Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Microbiology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Langston, Kelsey Murphey, "Identification of the Binding Partners for HspB2 and CryAB Reveals Myofibril and Mitochondrial Protein Interactions and Non-Redundant Roles for Small Heat Shock Proteins" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 3822. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3822 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Identification of the Binding Partners for HspB2 and CryAB Reveals Myofibril and Mitochondrial Protein Interactions and Non-Redundant Roles for Small Heat Shock Proteins Kelsey Langston A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Julianne H. Grose, Chair William R. McCleary Brian Poole Department of Microbiology and Molecular Biology Brigham Young University December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Kelsey Langston All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Identification of the Binding Partners for HspB2 and CryAB Reveals Myofibril and Mitochondrial Protein Interactors and Non-Redundant Roles for Small Heat Shock Proteins Kelsey Langston Department of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, BYU Master of Science Small Heat Shock Proteins (sHSP) are molecular chaperones that play protective roles in cell survival and have been shown to possess chaperone activity. -

Human Chromosome‐Specific Aneuploidy Is Influenced by DNA

Article Human chromosome-specific aneuploidy is influenced by DNA-dependent centromeric features Marie Dumont1,†, Riccardo Gamba1,†, Pierre Gestraud1,2,3, Sjoerd Klaasen4, Joseph T Worrall5, Sippe G De Vries6, Vincent Boudreau7, Catalina Salinas-Luypaert1, Paul S Maddox7, Susanne MA Lens6, Geert JPL Kops4 , Sarah E McClelland5, Karen H Miga8 & Daniele Fachinetti1,* Abstract Introduction Intrinsic genomic features of individual chromosomes can contri- Defects during cell division can lead to loss or gain of chromosomes bute to chromosome-specific aneuploidy. Centromeres are key in the daughter cells, a phenomenon called aneuploidy. This alters elements for the maintenance of chromosome segregation fidelity gene copy number and cell homeostasis, leading to genomic instabil- via a specialized chromatin marked by CENP-A wrapped by repeti- ity and pathological conditions including genetic diseases and various tive DNA. These long stretches of repetitive DNA vary in length types of cancers (Gordon et al, 2012; Santaguida & Amon, 2015). among human chromosomes. Using CENP-A genetic inactivation in While it is known that selection is a key process in maintaining aneu- human cells, we directly interrogate if differences in the centro- ploidy in cancer, a preceding mis-segregation event is required. It was mere length reflect the heterogeneity of centromeric DNA-depen- shown that chromosome-specific aneuploidy occurs under conditions dent features and whether this, in turn, affects the genesis of that compromise genome stability, such as treatments with micro- chromosome-specific aneuploidy. Using three distinct approaches, tubule poisons (Caria et al, 1996; Worrall et al, 2018), heterochro- we show that mis-segregation rates vary among different chromo- matin hypomethylation (Fauth & Scherthan, 1998), or following somes under conditions that compromise centromere function. -

Searching the Genomes of Inbred Mouse Strains for Incompatibilities That Reproductively Isolate Their Wild Relatives

Journal of Heredity 2007:98(2):115–122 ª The American Genetic Association. 2007. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esl064 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Advance Access publication January 5, 2007 Searching the Genomes of Inbred Mouse Strains for Incompatibilities That Reproductively Isolate Their Wild Relatives BRET A. PAYSEUR AND MICHAEL PLACE From the Laboratory of Genetics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706. Address correspondence to the author at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Identification of the genes that underlie reproductive isolation provides important insights into the process of speciation. According to the Dobzhansky–Muller model, these genes suffer disrupted interactions in hybrids due to independent di- vergence in separate populations. In hybrid populations, natural selection acts to remove the deleterious heterospecific com- binations that cause these functional disruptions. When selection is strong, this process can maintain multilocus associations, primarily between conspecific alleles, providing a signature that can be used to locate incompatibilities. We applied this logic to populations of house mice that were formed by hybridization involving two species that show partial reproductive isolation, Mus domesticus and Mus musculus. Using molecular markers likely to be informative about species ancestry, we scanned the genomes of 1) classical inbred strains and 2) recombinant inbred lines for pairs of loci that showed extreme linkage disequi- libria. By using the same set of markers, we identified a list of locus pairs that displayed similar patterns in both scans. These genomic regions may contain genes that contribute to reproductive isolation between M. domesticus and M. -

AVILA-DISSERTATION.Pdf

LOGOS EX MACHINA: A REASONED APPROACH TOWARD CANCER by Andrew Avila, B. S., M. S. A Dissertation In Biological Sciences Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved Lauren Gollahon Chairperson of the Committee Rich Strauss Sean Rice Boyd Butler Richard Watson Peggy Gordon Miller Dean of the Graduate School May, 2012 c 2012, Andrew Avila Texas Tech University, Andrew Avila, May 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge the incredible support given to me by my major adviser, Dr. Lauren Gollahon. Without your guidance surely I would not have made it as far as I have. Furthermore, the intellectual exchange I have shared with my advisory committee these long years have propelled me to new heights of inquiry I had not dreamed of even in the most lucid of my imaginings. That their continual intellectual challenges have provoked and evoked a subtle sense of natural wisdom is an ode to their efficacy in guiding the aspirant to the well of knowledge. For this initiation into the mysteries of nature I cannot thank my advisory committee enough. I also wish to thank the Vice President of Research for the fellowship which sustained the initial couple years of my residency at Texas Tech. Furthermore, my appreciation of the support provided to me by the Biology Department, financial and otherwise, cannot be understated. Finally, I also wish to acknowledge the individuals working at the High Performance Computing Center, without your tireless support in maintaining the cluster I would have not have completed the sheer amount of research that I have. -

Essential Genes and Their Role in Autism Spectrum Disorder

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder Xiao Ji University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Bioinformatics Commons, and the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Ji, Xiao, "Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2369. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2369 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2369 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder Abstract Essential genes (EGs) play central roles in fundamental cellular processes and are required for the survival of an organism. EGs are enriched for human disease genes and are under strong purifying selection. This intolerance to deleterious mutations, commonly observed haploinsufficiency and the importance of EGs in pre- and postnatal development suggests a possible cumulative effect of deleterious variants in EGs on complex neurodevelopmental disorders. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous, highly heritable neurodevelopmental syndrome characterized by impaired social interaction, communication and repetitive behavior. More and more genetic evidence points to a polygenic model of ASD and it is estimated that hundreds of genes contribute to ASD. The central question addressed in this dissertation is whether genes with a strong effect on survival and fitness (i.e. EGs) play a specific oler in ASD risk. I compiled a comprehensive catalog of 3,915 mammalian EGs by combining human orthologs of lethal genes in knockout mice and genes responsible for cell-based essentiality. -

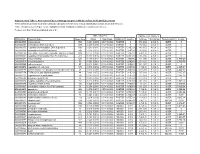

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, C12Q 1/70 (2006.01) HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US2018/056167 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 16 October 2018 (16. 10.2018) TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 62/573,025 16 October 2017 (16. 10.2017) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, ΓΕ , IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TECHNOLOGY [US/US]; 77 Massachusetts Avenue, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). -

16P11.2 Deletion Syndrome Guidebook

16p11.2 Deletion Syndrome Guidebook Page 1 Version 1.0, 12/11/2015 16p11.2 Deletion Syndrome Guidebook This guidebook was developed by the Simons VIP Connect Study Team to help you learn important information about living with the 16p11.2 deletion syndrome. Inside, you will find that we review everything from basic genetics and features of 16p11.2 deletion syndrome, to a description of clinical care and management considerations. - Simons VIP Connect Page 2 Version 1.0, 12/11/2015 Table of Contents How Did We Collect All of this Information? ................................................................................................ 4 What is Simons VIP Connect? ................................................................................................................... 4 What is the Simons Variation in Individuals Project (Simons VIP)? .......................................................... 5 Simons VIP Connect Research................................................................................................................... 5 Definition of 16p11.2 Deletion ..................................................................................................................... 6 What is a Copy Number Variant (CNV)? ................................................................................................... 7 Inheritance ................................................................................................................................................ 8 How is a 16p11.2 Deletion Found? .......................................................................................................... -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Definition of the Landscape of Promoter DNA Hypomethylation in Liver Cancer

Published OnlineFirst July 11, 2011; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3823 Cancer Therapeutics, Targets, and Chemical Biology Research Definition of the Landscape of Promoter DNA Hypomethylation in Liver Cancer Barbara Stefanska1, Jian Huang4, Bishnu Bhattacharyya1, Matthew Suderman1,2, Michael Hallett3, Ze-Guang Han4, and Moshe Szyf1,2 Abstract We use hepatic cellular carcinoma (HCC), one of the most common human cancers, as a model to delineate the landscape of promoter hypomethylation in cancer. Using a combination of methylated DNA immunopre- cipitation and hybridization with comprehensive promoter arrays, we have identified approximately 3,700 promoters that are hypomethylated in tumor samples. The hypomethylated promoters appeared in clusters across the genome suggesting that a high-level organization underlies the epigenomic changes in cancer. In normal liver, most hypomethylated promoters showed an intermediate level of methylation and expression, however, high-CpG dense promoters showed the most profound increase in gene expression. The demethylated genes are mainly involved in cell growth, cell adhesion and communication, signal transduction, mobility, and invasion; functions that are essential for cancer progression and metastasis. The DNA methylation inhibitor, 5- aza-20-deoxycytidine, activated several of the genes that are demethylated and induced in tumors, supporting a causal role for demethylation in activation of these genes. Previous studies suggested that MBD2 was involved in demethylation of specific human breast and prostate cancer genes. Whereas MBD2 depletion in normal liver cells had little or no effect, we found that its depletion in human HCC and adenocarcinoma cells resulted in suppression of cell growth, anchorage-independent growth and invasiveness as well as an increase in promoter methylation and silencing of several of the genes that are hypomethylated in tumors. -

How Genes Work

Help Me Understand Genetics How Genes Work Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health Department of Health & Human Services Table of Contents 1 What are proteins and what do they do? 1 2 How do genes direct the production of proteins? 5 3 Can genes be turned on and off in cells? 7 4 What is epigenetics? 8 5 How do cells divide? 10 6 How do genes control the growth and division of cells? 12 7 How do geneticists indicate the location of a gene? 16 Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics (https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/) i How Genes Work 1 What are proteins and what do they do? Proteins are large, complex molecules that play many critical roles in the body. They do most of the work in cells and are required for the structure, function, and regulation of thebody’s tissues and organs. Proteins are made up of hundreds or thousands of smaller units called amino acids, which are attached to one another in long chains. There are 20 different types of amino acids that can be combined to make a protein. The sequence of amino acids determineseach protein’s unique 3-dimensional structure and its specific function. Aminoacids are coded by combinations of three DNA building blocks (nucleotides), determined by the sequence of genes. Proteins can be described according to their large range of functions in the body, listed inalphabetical order: Antibody. Antibodies bind to specific foreign particles, such as viruses and bacteria, to help protect the body. Example: Immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Figure 1) Enzyme.