Evaluation Report Community Based Health Development Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAGWAY REGION, MAGWAY DISTRICT Natmauk Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census MAGWAY REGION, MAGWAY DISTRICT Natmauk Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Magway Region, Magway District Natmauk Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Magway Region, showing the townships Natmauk Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 206,996 2 Population males 92,774 (44.8%) Population females 114,222 (55.2%) Percentage of urban population 7.1% Area (Km2) 2,309.2 3 Population density (per Km2) 89.6 persons Median age 29.3 years Number of wards 7 Number of village tracts 73 Number of private households 48,426 Percentage of female headed households 27.7% Mean household size 4.2 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 29.3% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 62.6% Elderly population (65+ years) 8.1% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 59.8 Child dependency ratio 46.8 Old dependency ratio 13.0 Ageing index 27.8 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 81 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 87.6% Male 96.1% Female 81.4% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 8,968 4.3 Walking 3,974 1.9 Seeing 4,841 2.3 Hearing 2,693 1.3 Remembering 3,062 1.5 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 132,226 78.7 -

Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma

To: Hon. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General United Nations From: Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma CC: Mr. B. Lynn Pascoe, Under-Secretary-General, United Nations Mr. Ibrahim Gambari, Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser to the Secretary- General on Myanmar/Burma Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the five Permanent Members (China, Russia, France, United Kingdom and the United states) of the UN Security Council U Aung Shwe, Chairman, National League for Democracy Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, General Secretary, National League for Democracy U Aye Thar Aung, Secretary, Committee Representing the Peoples' Parliament (CRPP) Veteran Politicians The 88 Generation Students Date: 1 August 2007 Re: National Reconciliation and Democratization in Myanmar/Burma Dear Excellency, We note that you have issued a statement on 18 July 2007, in which you urged the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) (the ruling military government of Myanmar/Burma) to "seize this opportunity to ensure that this and subsequent steps in Myanmar's political roadmap are as inclusive, participatory and transparent as possible, with a view to allowing all the relevant parties to Myanmar's national reconciliation process to fully contribute to defining their country's future."1 We thank you for your strong and personal involvement in Myanmar/Burma and we expect that your good offices mandate to facilitating national reconciliation in Myanmar/Burma would be successful. We, Members of Parliament elected by the people of Myanmar/Burma in the 1990 general elections, also would like to assure you that we will fully cooperate with your good offices and the United Nations in our effort to solve problems in Myanmar/Burma peacefully through a meaningful, inclusive and transparent dialogue. -

30 May 2021 1 30 May 21 Gnlm

MONASTIC EDUCATION SCHOOLS, RELIABLE FOR CHILDREN BOTH FROM URBAN AND RURAL AREAS PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Union Minister U Aung Naing Oo inspects Night market to be built in investment activities in Magway Region Magway PAGE-3 PAGE-3 Vol. VIII, No. 41, 5th Waning of Kason 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Sunday, 30 May 2021 Announcement of Union Election Commission 29 May 2021 1. Regarding the Multiparty General Election held on 8 November 2020, the Union Election Commission has inspected the voter lists and the casting of votes of Khamti, Homalin, Leshi, Lahe, Nanyun, Mawlaik and Phaungpyin townships of Sagaing Region. 2. According to the inspection, the previous election commission released 401,918 eligible voters in these seven townships of Sagaing Region. The list of the Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population in November 2020 showed 321,347 eligible voters who had turned 18. The voter lists mentioned that there were 51,461 citizens, associate citizens, naturalized citizens, and non-identity voters, 8,840 persons repeated on the voter lists more than three times and 48,932 persons repeated on the voter lists two times. SEE PAGE-6 Magway Region to develop new eco-tourism INSIDE TODAY NATIONAL Union Minister site near Shwesettaw area U Chitt Naing A new eco-tourism destina- meets Information tion will be developed within Ministry the Shwesettaw area in Minbu employees Township, according to the Mag- PAGE-4 way Region Directorate of Ho- tels and Tourism Department. Under the management of NATIONAL the Magway Region Administra- Yangon workers’ tion Council and with the sug- hospital reaccepts gestion of the Ministry of Hotels inpatients except for and Tourism, the project will major surgery cases be implemented on the 60-acre PAGE-4 large area on the right side of Hlay Tin bridge situated on the Minbu-Shwesettaw road. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

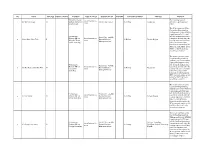

Warrant Lists English

No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Minister of Social For encouraging civil Issued warrant to 1 Dr. Win Myat Aye M Welfare, Relief and Penal Code S:505-a In Hiding Naypyitaw servants to participate in arrest Resettlement CDM The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 2 (Daw) Phyu Phyu Thin F Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region Mingalar Taung arrest coup in response to military Management law Nyunt Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 3 (U) Yee Mon (aka) U Tin Thit M Natural Disaster In Hiding Naypyitaw Potevathiri arrest coup in response to military Management law Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and self-declared parliamentary Pyihtaungsu Penal Code - 505(B), Issued warrant to committee formed after the 4 (U) Tun Myint M Hluttaw MP for Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region arrest coup in response to military Bahan Township Management law rule. -

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. in Five

GAZETTEER OF UPPER BURMA AND THE SHAN STATES. IN FIVE VOLUMES. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL PAPERS BY J. GEORGE SCOTT. BARRISTER-AT-LAW, C.I.E., M.R.A.S., F.R.G.S., ASSISTED BY J. P. HARDIMAN, I.C.S. PART II.--VOL. III. RANGOON: PRINTED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA. 1901. [PART II, VOLS. I, II & III,--PRICE: Rs. 12-0-0=18s.] CONTENTS. VOLUME III. Page. Page. Page. Ralang 1 Sagaing 36 Sa-le-ywe 83 Ralôn or Ralawn ib -- 64 Sa-li ib. Rapum ib -- ib. Sa-lim ib. Ratanapura ib -- 65 Sa-lin ib. Rawa ib. Saga Tingsa 76 -- 84 Rawkwa ib. Sagônwa or Sagong ib. Salin ib. Rawtu or Maika ib. Sa-gu ib. Sa-lin chaung 86 Rawva 2 -- ib. Sa-lin-daung 89 Rawvan ib. Sagun ib -- ib. Raw-ywa ib. Sa-gwe ib. Sa-lin-gan ib. Reshen ib. Sa-gyan ib. Sa-lin-ga-thu ib. Rimpi ib. Sa-gyet ib. Sa-lin-gôn ib. Rimpe ib. Sagyilain or Limkai 77 Sa-lin-gyi ib. Rosshi or Warrshi 3 Sa-gyin ib -- 90 Ruby Mines ib. Sa-gyin North ib. Sallavati ib. Ruibu 32 Sa-gyin South ib. Sa-lun ib. Rumklao ib. a-gyin San-baing ib. Salween ib. Rumshe ib. Sa-gyin-wa ib. Sama 103 Rutong ib. Sa-gyu ib. Sama or Suma ib. Sai Lein ib. Sa-me-gan-gôn ib. Sa-ba-dwin ib. Saileng 78 Sa-meik ib. Sa-ba-hmyaw 33 Saing-byin North ib. Sa-meik-kôn ib. Sa-ban ib. -

MAGWAY REGION, MAGWAY DISTRICT Magway Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census MAGWAY REGION, MAGWAY DISTRICT Magway Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Magway Region, Magway District Magway Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1: Map of Magway Region, showing the townships Magway Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 289,247 2 Population males 135,103 (46.7%) Population females 154,144 (53.3%) Percentage of urban population 32.5% Area (Km2) 1,767.0 3 Population density (per Km2) 163.7 persons Median age 29.2 years Number of wards 15 Number of village tracts 61 Number of private households 68,677 Percentage of female headed households 23.0% Mean household size 4.0 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 25.8% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 67.5% Elderly population (65+ years) 6.7% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 48.1 Child dependency ratio 38.2 Old dependency ratio 9.9 Ageing index 26.0 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 88 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 92.9% Male 97.0% Female 89.6% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 9,833 3.4 Walking 4,282 1.5 Seeing 4,871 1.7 Hearing 2,782 1.0 Remembering 3,084 1.1 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 187,015 77.7 -

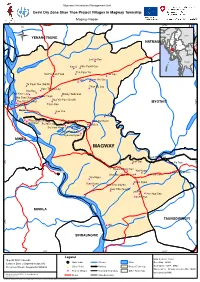

Mimu1054v01 3 Sep 13 Cesvi Dry Zone Shae Thoe Project

Myanmar Information Management Unit Cesvi Dry Zone Shae Thoe Project Villages in Magway Township Magway Region 95°0'E 95°10'E 95°20'E Natmauk INDIA Kachin CHINA YENANGYAUNG Sagaing Ü NATMAUK 20°20'N 20°20'N Chin Shan Mandalay Rakhine Magway Naypyitaw LAOS Kayah Bago Yangon Ayeyarwady Kayin Let Se Kan ! Mon THAILAND Kan U Khin Pyant Gyi ! ! Tanintharyi Tha Pyay Yin Tei Pin Kan Pauk ! Leik Kan ! ! Kone Gyi Ywar Thit Gyi ! ! Ta Pauk Taw (North) ! Than Bo Lay Ywar Thit Ka Lay ! Nat Kan ! ! Kan Ywar Lay ! Khway Tauk San !Wet Thaik ! War Taw Chaung ! Hpa Yar Pyo (South) Tha Yet Pin Kwet ! ! MYOTHIT 20°10'N Kyun Su ! San Kan 20°10'N Magway San Yoe ! Sa Lan ! Myin Kin ! ! ! Thin Baw Seik ! Than Man Tha Lin !Aw Zar Kone Chaung Hpyu Pu Htoe San ! ! !Ta Moet Sat Pyar Kone / Si Pin Thar Kyar Pyit Inn ! ! Kyaung Pyauk MINBU MAGWAY Kyauk Pyit Kone ! San Gyi ! 20°0'N ! Lat Pa Taw 20°0'N Nyaung Kyat San ! Yae Kyaw Minhla ! ! Hpoe Pauk Kan Shar Bo / Wet Lu San ! !Ah Sa San Yae Ngan ! Shwe Kyaw ! Yone Kone Kun Ohn (North) ! ! Kun Ohn (South) ! Let Pan ! ! Pan Nyo San !In Pin Tan MINHLA TAUNGDWINGYI 19°50'N 19°50'N !! ! Min SINBAUNGWE 95°0'E 95°10'E 95°20'E Legend Data Sources : Cesvi Map ID: MIMU1054v01 Main Town Stream River Base Map - MIMU Creation Date: 3 September 2013.A3 Boundaries - WFP / MIMU Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 (! Other Town Railway Project Township Place names - Ministry of Home Affair (GAD) ! Project Villages Township Boundary Other Townships translated by MIMU Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] www.themimu.info Road State Boundary Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address Contact No 1 SHOWROOM_O2 MAHARBANDOOLA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.212, PANSODAN ST. (MIDDLE BLOCK), KYAWKTADAR TSP 09 420162256 2 SHOWROOM_O2 BAGO (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION BAGO DISTRICT BAGO TOWNSHIP SHIN SAW PU QUARTER, BAGO TSP 09 967681616 3 SHOW ROOM _O2 _(SULE) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.118, SULAY PAGODA RD, KYAUKTADAR TSP 09 454147773 4 SHOWROOM_MOBILE KING ZEWANA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT THINGANGYUN TOWNSHIP BLDG NO.38, ROOM B1, GROUND FL, LAYDAUNKAN ST, THINGANGYUN 09 955155994 5 SHOWROOM_M9_78ST(MM) UPPER MYANMAR MANDALAY REGION MANDALAY DISTRICT CHANAYETHAZAN TOWNSHIP NO.D3, 78 ST, BETWEEN 27 ST AND 28 ST, CHANAYETHARSAN TSP 09 977895028 6 SHOWROOM_M9 MAGWAY (MM) UPPER MYANMAR MAGWAY REGION MAGWAY DISTRICT MAGWAY TOWNSHIP MAGWAY TSP 09 977233181 7 SHOWROOM_M9_TAUNGYI (LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYIUPPER TSP) (MM) MYANMAR SHAN STATE TAUNGGYI DISTRICT TAUNGGYI TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYI TSP 09 977233182 8 SHOWROOM_M9 PYAY (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION PYAY DISTRICT PYAY TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, PYAY TSP 09 5376699 9 SHOWROOM_M9 MONYWA (MM), BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWAUPPER TOWNSHIP MYANMAR SAGAING REGION MONYWA DISTRICT MONYWA TOWNSHIP BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWA TSP. 09 977233179 10 SHOWROOM _O2_(BAK) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT BOTATAUNG TOWNSHIP BO AUNG KYAW ROAD, LOWER 09 428189521 11 SHOWROOM_EXCELLENT (YAYKYAW) (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON -

Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination Document Status: Final Project Number: 47152 June 2016 Myanmar: Irrigated Agriculture Inclusive Development Project This initial environmental evaluation is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 September 2015) Currency unit – Myanmar Kyats Kyats 1.00 = US $0.0007855 US $1.00 = MMK 1,273 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADRA – Adventist Development and Relief Agency CDZ – Central Dry Zone DAP – Department of Agricultural Planning, MOALI DAR – Department of Agricultural Research, MOALI DOA – Department of Agriculture, MOALI EA – executing agency EARF – environmental assessment and review framework ECD – Environmental Conservation Department, under MOECAF EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan GRC – Grievance Redress Committee GRM – Grievance Redress Mechanism IEE – initial environmental examination IA – implementing agency IAIDP – Irrigated Agriculture Inclusive Development Project IPSA – Initial Poverty and Social Analysis IWUMD – Irrigation and Water Utilization Management Department, MOALI LIEC – Loan -

Myanmar Dry Zone Development Programme Scoping Report

Myanmar Dry Zone Development Programme Scoping Report December 2014 FAO Investment Centre i Foreword from the LIFT Fund Director This report was commissioned by the Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund (LIFT) as part of the process of designing a new LIFT programme for the central dry zone (DZ) of Myanmar. The report was written by a team from the FAO Investment Centre following field work in 2013 and 2014. The report includes the results of field work carried out in the preselected target area for the programme: Myingyan, Taungtha, Natogyi and Mahlaing in Mandalay Region and Pakokku and Yesagyo in Magway Region. The report presents a number of options for LIFT’s future DZ programme with a special focus on increasing on-farm and off-farm incomes and improving the well-being of the rural poor, and building on the learning of current and previous projects in the region by both LIFT partners and other development partners. However, the FAO team did not participate in the consultations that the LIFT Fund Management Office conducted in July and August 2014, and the report does not reference the new LIFT strategy on 2014. Therefore, the report should be read as an important contribution to the development of LIFT’s DZ programme, but it should not be construed as a description of the final programme that will emerge. We expect that a series of calls for proposals will be launched in January and February of 2015, each of which will articulate more precisely the outcomes of the programme and the kinds of activities that LIFT would like to implement as part of the programme. -

Republic of the Union of Myanmar Preparatory Survey on Distribution

Electricity Supply Enterprise Ministry of Electric Power Republic of the Union of Myanmar Republic of the Union of Myanmar Preparatory Survey on Distribution System Improvement Project in Main Cities Final Report July 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Chubu Electric Power Co., Inc. 1R Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. JR 15-033 Table of contents Chapter 1 Background ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Survey schedule .......................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.3 JICA survey team and counterpart .............................................................................................. 1-5 Chapter 2 Present Status ........................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1 Present status of the power distribution sector ........................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Movement of Corporatization and franchising ........................................................................... 2-6 2.3 Electricity Tariff .......................................................................................................................... 2-7 2.3.1 Number of Consumers .......................................................................................................