Myanmar Dry Zone Development Programme Scoping Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study on Profitability of Small Groundnut Oil Mills in Myingyan Township, Mandalay Region

CASE STUDY ON PROFITABILITY OF SMALL GROUNDNUT OIL MILLS IN MYINGYAN TOWNSHIP, MANDALAY REGION AUNG PHYO OCTOBER 2016 CASE STUDY ON PROFITABILITY OF SMALL GROUNDNUT OIL MILLS IN MYINGYAN TOWNSHIP, MANDALAY REGION AUNG PHYO A Thesis Submitted to the Post-Graduate Committee of the Yezin Agricultural University as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Agricultural Science (Agricultural Economics) Department of Agricultural Economics Yezin Agricultural University OCTOBER 2016 Copyright© [2016 – by Aung Phyo] All rights reserved. The thesis attached here to, entitled “Case Study on Profitability of Small Groundnut Oil Mills in Myingyan Twonship, Mandalay Region” was prepared and submitted by Aung Phyo under the direction of the chairperson of the candidate supervisory committee and has been approved by all members of that committee and board of examiners as a partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Agricultural Science (Agricultural Economics). ------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------- Dr. Cho Cho San Dr. Khin Oo Chairperson External Examiner Supervisory Committee Supervisory Committee Professor and Head Professor and Principal (Retd.) Department of Agricultural Economics Rice Crop Specialization Yezin Agricultural University Yezin Agricultural University (Hmawbi) Yezin, Nay Pyi Taw Yezin, Nay Pyi Taw ------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------- Dr. Nay Myo Aung Dr. Thet Lin Member Member Supervisory -

30 May 2021 1 30 May 21 Gnlm

MONASTIC EDUCATION SCHOOLS, RELIABLE FOR CHILDREN BOTH FROM URBAN AND RURAL AREAS PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Union Minister U Aung Naing Oo inspects Night market to be built in investment activities in Magway Region Magway PAGE-3 PAGE-3 Vol. VIII, No. 41, 5th Waning of Kason 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Sunday, 30 May 2021 Announcement of Union Election Commission 29 May 2021 1. Regarding the Multiparty General Election held on 8 November 2020, the Union Election Commission has inspected the voter lists and the casting of votes of Khamti, Homalin, Leshi, Lahe, Nanyun, Mawlaik and Phaungpyin townships of Sagaing Region. 2. According to the inspection, the previous election commission released 401,918 eligible voters in these seven townships of Sagaing Region. The list of the Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population in November 2020 showed 321,347 eligible voters who had turned 18. The voter lists mentioned that there were 51,461 citizens, associate citizens, naturalized citizens, and non-identity voters, 8,840 persons repeated on the voter lists more than three times and 48,932 persons repeated on the voter lists two times. SEE PAGE-6 Magway Region to develop new eco-tourism INSIDE TODAY NATIONAL Union Minister site near Shwesettaw area U Chitt Naing A new eco-tourism destina- meets Information tion will be developed within Ministry the Shwesettaw area in Minbu employees Township, according to the Mag- PAGE-4 way Region Directorate of Ho- tels and Tourism Department. Under the management of NATIONAL the Magway Region Administra- Yangon workers’ tion Council and with the sug- hospital reaccepts gestion of the Ministry of Hotels inpatients except for and Tourism, the project will major surgery cases be implemented on the 60-acre PAGE-4 large area on the right side of Hlay Tin bridge situated on the Minbu-Shwesettaw road. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

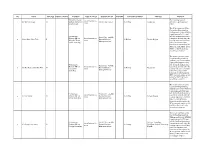

Warrant Lists English

No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Minister of Social For encouraging civil Issued warrant to 1 Dr. Win Myat Aye M Welfare, Relief and Penal Code S:505-a In Hiding Naypyitaw servants to participate in arrest Resettlement CDM The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 2 (Daw) Phyu Phyu Thin F Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region Mingalar Taung arrest coup in response to military Management law Nyunt Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and Pyihtaungsu self-declared parliamentary Penal Code - 505(B), Hluttaw MP for Issued warrant to committee formed after the 3 (U) Yee Mon (aka) U Tin Thit M Natural Disaster In Hiding Naypyitaw Potevathiri arrest coup in response to military Management law Township rule. The warrants were issued at each township the MPs represent, under article 505[b) of the Penal Code, according to sources. The 17 are members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), a predominantly NLD and self-declared parliamentary Pyihtaungsu Penal Code - 505(B), Issued warrant to committee formed after the 4 (U) Tun Myint M Hluttaw MP for Natural Disaster In Hiding Yangon Region arrest coup in response to military Bahan Township Management law rule. -

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. in Five

GAZETTEER OF UPPER BURMA AND THE SHAN STATES. IN FIVE VOLUMES. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL PAPERS BY J. GEORGE SCOTT. BARRISTER-AT-LAW, C.I.E., M.R.A.S., F.R.G.S., ASSISTED BY J. P. HARDIMAN, I.C.S. PART II.--VOL. III. RANGOON: PRINTED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA. 1901. [PART II, VOLS. I, II & III,--PRICE: Rs. 12-0-0=18s.] CONTENTS. VOLUME III. Page. Page. Page. Ralang 1 Sagaing 36 Sa-le-ywe 83 Ralôn or Ralawn ib -- 64 Sa-li ib. Rapum ib -- ib. Sa-lim ib. Ratanapura ib -- 65 Sa-lin ib. Rawa ib. Saga Tingsa 76 -- 84 Rawkwa ib. Sagônwa or Sagong ib. Salin ib. Rawtu or Maika ib. Sa-gu ib. Sa-lin chaung 86 Rawva 2 -- ib. Sa-lin-daung 89 Rawvan ib. Sagun ib -- ib. Raw-ywa ib. Sa-gwe ib. Sa-lin-gan ib. Reshen ib. Sa-gyan ib. Sa-lin-ga-thu ib. Rimpi ib. Sa-gyet ib. Sa-lin-gôn ib. Rimpe ib. Sagyilain or Limkai 77 Sa-lin-gyi ib. Rosshi or Warrshi 3 Sa-gyin ib -- 90 Ruby Mines ib. Sa-gyin North ib. Sallavati ib. Ruibu 32 Sa-gyin South ib. Sa-lun ib. Rumklao ib. a-gyin San-baing ib. Salween ib. Rumshe ib. Sa-gyin-wa ib. Sama 103 Rutong ib. Sa-gyu ib. Sama or Suma ib. Sai Lein ib. Sa-me-gan-gôn ib. Sa-ba-dwin ib. Saileng 78 Sa-meik ib. Sa-ba-hmyaw 33 Saing-byin North ib. Sa-meik-kôn ib. Sa-ban ib. -

MAGWAY REGION, MAGWAY DISTRICT Magway Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census MAGWAY REGION, MAGWAY DISTRICT Magway Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Magway Region, Magway District Magway Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1: Map of Magway Region, showing the townships Magway Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 289,247 2 Population males 135,103 (46.7%) Population females 154,144 (53.3%) Percentage of urban population 32.5% Area (Km2) 1,767.0 3 Population density (per Km2) 163.7 persons Median age 29.2 years Number of wards 15 Number of village tracts 61 Number of private households 68,677 Percentage of female headed households 23.0% Mean household size 4.0 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 25.8% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 67.5% Elderly population (65+ years) 6.7% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 48.1 Child dependency ratio 38.2 Old dependency ratio 9.9 Ageing index 26.0 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 88 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 92.9% Male 97.0% Female 89.6% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 9,833 3.4 Walking 4,282 1.5 Seeing 4,871 1.7 Hearing 2,782 1.0 Remembering 3,084 1.1 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 187,015 77.7 -

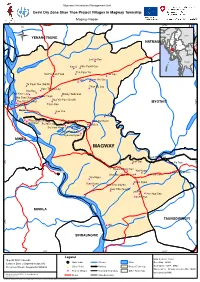

Mimu1054v01 3 Sep 13 Cesvi Dry Zone Shae Thoe Project

Myanmar Information Management Unit Cesvi Dry Zone Shae Thoe Project Villages in Magway Township Magway Region 95°0'E 95°10'E 95°20'E Natmauk INDIA Kachin CHINA YENANGYAUNG Sagaing Ü NATMAUK 20°20'N 20°20'N Chin Shan Mandalay Rakhine Magway Naypyitaw LAOS Kayah Bago Yangon Ayeyarwady Kayin Let Se Kan ! Mon THAILAND Kan U Khin Pyant Gyi ! ! Tanintharyi Tha Pyay Yin Tei Pin Kan Pauk ! Leik Kan ! ! Kone Gyi Ywar Thit Gyi ! ! Ta Pauk Taw (North) ! Than Bo Lay Ywar Thit Ka Lay ! Nat Kan ! ! Kan Ywar Lay ! Khway Tauk San !Wet Thaik ! War Taw Chaung ! Hpa Yar Pyo (South) Tha Yet Pin Kwet ! ! MYOTHIT 20°10'N Kyun Su ! San Kan 20°10'N Magway San Yoe ! Sa Lan ! Myin Kin ! ! ! Thin Baw Seik ! Than Man Tha Lin !Aw Zar Kone Chaung Hpyu Pu Htoe San ! ! !Ta Moet Sat Pyar Kone / Si Pin Thar Kyar Pyit Inn ! ! Kyaung Pyauk MINBU MAGWAY Kyauk Pyit Kone ! San Gyi ! 20°0'N ! Lat Pa Taw 20°0'N Nyaung Kyat San ! Yae Kyaw Minhla ! ! Hpoe Pauk Kan Shar Bo / Wet Lu San ! !Ah Sa San Yae Ngan ! Shwe Kyaw ! Yone Kone Kun Ohn (North) ! ! Kun Ohn (South) ! Let Pan ! ! Pan Nyo San !In Pin Tan MINHLA TAUNGDWINGYI 19°50'N 19°50'N !! ! Min SINBAUNGWE 95°0'E 95°10'E 95°20'E Legend Data Sources : Cesvi Map ID: MIMU1054v01 Main Town Stream River Base Map - MIMU Creation Date: 3 September 2013.A3 Boundaries - WFP / MIMU Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 (! Other Town Railway Project Township Place names - Ministry of Home Affair (GAD) ! Project Villages Township Boundary Other Townships translated by MIMU Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] www.themimu.info Road State Boundary Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Mandalay Region, Myanmar

MyanmarInformation Manage meUnit nt KyaukpadaungTownship MandalayRegion, Myanmar 95°0'E 95°10'E 95°20'E 95°30'E 21°10'N 21°10'N (! Ngathayauk / ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Taungtha ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Township ! ! ! ! ! !HtaukShar ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Nyaung-U ! ! ! ! ! Township ! ! ! !SaingKhaung ! KharPat ! ! ! ! MyinThar Taung ! ! ! ! SeikTein (North) ! KanHpyu ! ! SeikTein (South) ! ! ! ! ! Kye eKan ! ! ! !YGyi ar Taw(East) ! ! !Y oneKyin YGyi ar Taw(W e st) !ThanPin ! ! ! ! ! Su HpyuSu Kone ! GonTaw Htan PaukHtan Kone ! ! MyinChan Kone ! ! ! KyarNay Aint ! !Y aeNgan ! ! ! ! ! LelYar Chauk!Htan ThaPinNat Pin (a) ! !ThaYeTaw t ! LelGyi Myauk ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !KhwayTaukKone ! LayPin(North) MyaukKone MaGyi Su ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! KanKone ! ! !ThanGyi Kone LayPin(South) ThaYeCho t Kone DeeDoke Kone ! ! 21°0'N ! 21°0'N KonePaw! Net !TheeKone (W e st) ! ! SonKone Mahlaing ! HlaingThar ! ! !TheeKone (East) ! ! !DaungLel PinPu ! Township KanBarTe (North) ! !MaSoe Yain ! ! !ThoneEinKone ! KanBarTe (South) ! KyaukGarTa ! ! ! ! ChaungChar ! TaungHla ! ! MyaukTaw ! Kan Zat KoneKanZat ! Chaing ! SinSin ! ! ! !LelKu SarKyin ! !ShweSiTaing (Shwe SeTaing) !TaungPaw (North) ! ! Ku NgarKoneYant !Y warThitKaLay ! !TheePin ! ! ! TaungPaw(South) ThanKone ! KyaukKhwet ! ! PopaLwin ! !Y aeLayKa !LelDi ! !TawZar Chaung Popa ThaPyay Kaing ! ! !NaYwe Taw ! KyinGaung Nat KanLel!Nat ! !KyunKhin Gyi !ThinPaung TaungLatKa ! !ChaungHpyar ! ThanBo Ywar Thit ! ! PyinMaGyi (North)(Lel Kyin Khaung) ThanBo ! !PyinMaGyi (South) !ThitTein ! ! Se !KyatKhweHnit -

A Study on Obstacles of Small-Scale Paddy Farmers

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME A STUDY ON OBSTACLES OF SMALL-SCALE PADDY FARMERS IN DRY ZONE WAI PHYO THEIN EMDevS – 75 (14th Batch) AUGUST, 2019 i YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME A STUDY ON OBSTACLES OF SMALL-SCALE PADDY FARMERS IN DRY ZONE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of Development Studies. Supervised by: Submitted by: Daw Than Win Htay Wai Phyo Thein Lecturer Roll No.75 Yangon University of Economics EMDevS 14th Batch AUGUST, 2019 ii YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME This is to certify that this thesis entitled “A Study on Obstacles of Small-Scale Paddy Farmers in Dry Zone” submitted as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the degree of Master of Development Studies, has been accepted by the Board of Examiners. BOARD OF EXAMINER 1. Dr. Tin Win Rector Yangon University of Economics (Chief Examiner) 2. Dr. Ni Lar Myint Htoo Pro-Rector Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 3. Dr. Kyaw Min Htun Pro-Rector (Retired) Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 4. Dr. Cho Cho Thein Professor and Head Department of Economics Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 5. Dr. Tha Pye Nyo Professor Department of Economics Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) AUGUST, 2019 iii ABSTRACT This study focused on obstacles faced by small-scale paddy farmers in Taungtha Township which is located in Dry Zone. This study used descriptive method and is cross-sectional study. It targeted the farmers in the Taungtha township, who possess five acres of farm land maximum and cultivated the paddy since last three years at least, to explore their major obstacles via the questionnaire. -

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address Contact No 1 SHOWROOM_O2 MAHARBANDOOLA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.212, PANSODAN ST. (MIDDLE BLOCK), KYAWKTADAR TSP 09 420162256 2 SHOWROOM_O2 BAGO (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION BAGO DISTRICT BAGO TOWNSHIP SHIN SAW PU QUARTER, BAGO TSP 09 967681616 3 SHOW ROOM _O2 _(SULE) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.118, SULAY PAGODA RD, KYAUKTADAR TSP 09 454147773 4 SHOWROOM_MOBILE KING ZEWANA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT THINGANGYUN TOWNSHIP BLDG NO.38, ROOM B1, GROUND FL, LAYDAUNKAN ST, THINGANGYUN 09 955155994 5 SHOWROOM_M9_78ST(MM) UPPER MYANMAR MANDALAY REGION MANDALAY DISTRICT CHANAYETHAZAN TOWNSHIP NO.D3, 78 ST, BETWEEN 27 ST AND 28 ST, CHANAYETHARSAN TSP 09 977895028 6 SHOWROOM_M9 MAGWAY (MM) UPPER MYANMAR MAGWAY REGION MAGWAY DISTRICT MAGWAY TOWNSHIP MAGWAY TSP 09 977233181 7 SHOWROOM_M9_TAUNGYI (LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYIUPPER TSP) (MM) MYANMAR SHAN STATE TAUNGGYI DISTRICT TAUNGGYI TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYI TSP 09 977233182 8 SHOWROOM_M9 PYAY (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION PYAY DISTRICT PYAY TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, PYAY TSP 09 5376699 9 SHOWROOM_M9 MONYWA (MM), BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWAUPPER TOWNSHIP MYANMAR SAGAING REGION MONYWA DISTRICT MONYWA TOWNSHIP BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWA TSP. 09 977233179 10 SHOWROOM _O2_(BAK) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT BOTATAUNG TOWNSHIP BO AUNG KYAW ROAD, LOWER 09 428189521 11 SHOWROOM_EXCELLENT (YAYKYAW) (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON -

Myingyan Degree College-2017 ,Vol-8-Compressed

1 Myingyan Degree College Research Journal Vol .8, 2017 Study and Analysis on Composition Sakkarajs of Three Eigyins of Taungngu Period Tin Oo* Abstract This paper deals with the study and analysis on the composition sakkarajs (Myanmar Era) of such eigyins (classical poems addressed to a royal child extolling the glory of ancestors) as MintayarmedawEigyin, Minyekyawzwar Son Eigyin and Thakhingyi Eigyin appeared in Taungngu Period. This paper reveals the differences in the traditional specifications with regard to the composition sakkarajs of these eigyins comparing and conferring with the chronicles. Introduction The eigyingabyar (classical poem addressed to a royal child extolling the glory of ancestors; the verse begins and ends with the word ‘‘ei’’) is a kind of long ‘‘teigabyar’’(song verse or poem) soothing the royal child. It is a poem composed for the royal sons, daughters and lineages in infancy and beyond infancy. It is also a poem composing with ‘‘ei’’ k ranta or karyan (vowel sound of the letter; rhyma) at the end. The subject matters are the patriotism stimulating performances of the royal great- grandfather, royal father and royal relatives worthy of the highest praise composing eigyin. Therefore, it may be said that eigyin poem is a kind of ‘‘zartiman’’(national spirit; pride of one’s race and nation; pride of one’s lineage) literature capable of stimulating the zartithwei- zartiman (national spirit; hereditary pride and courage; patriotism). It may be designed as a kind of literature with historical value as it is like the contemporary record of that period. Throughout the history of Myanmar literature, 67 eigyins are found. -

Identifying Priority Investments in Water in Myanmar's Dry Zone Final

Identifying priority investments in water in Myanmar’s Dry Zone Final Report for Component 3 Robyn Johnston 1, Rajah Ameer 1, Soumya Balasubramanya 1, Somphasith Douangsavanh 2, Guillaume Lacombe 2, Matthew McCartney 2, Paul Pavelic 2, Sonali Senaratna Sellamuttu 2, Touleelor Sotoukee 2, Diana Suhardiman 2 and Olivier Joffre 3 1IWMI, Colombo, Sri Lanka 2IWMI, Vientiane, Lao PDR 3Independent Consultant CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Acronyms 3 Summary 4 1 Introduction 8 2 Approach and Methodology 9 2.1 Conceptual framework 9 2.2 Methodology 10 3 Water and livelihoods in the Dry Zone 12 3.1 Agro-ecosystems of the Dry Zone 12 3.2 Water-related issues by agro-ecosystem 15 3.3 Groundwater and livelihoods 18 4. Identifying interventions 21 4.1 Current and past programs and investments – patterns and outcomes 22 4.2 Community needs and preferences 27 4.3 Physical constraints and limits to WR development (from Report 1) 28 4.4 International programs on AWM 29 5. Priority interventions 32 5.1 Improving the performance of formal irrigation systems 32 5.2 Groundwater interventions 35 5.3 Rainwater harvesting: village reservoirs and small farm dams 39 5.4 SWC / Watershed management 42 5.5 Water resources planning and information 45 6. Summary of Recommendations 49 References 51 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank Australia, Denmark, the European Union, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and the United States of America for their kind contributions to improving the livelihoods and food security of the poorest and most vulnerable people in Myanmar. Their support to the Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund (LIFT) is gratefully acknowledged.