Mission Kashmir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

Inclusion and Cultural Preservation for the Ifugao People

421 Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights, Vol.2 No. 2 December 2018. pp. 421-447 doi: 10.19184/jseahr.v2i2.8232 © University of Jember & Indonesian Consortium for Human Rights Lecturers Inclusion and Cultural Preservation for the Ifugao People Ellisiah U. Jocson Managing Director, OneLife Foundation Inc. (OLFI), M.A.Ed Candidate, University of the Philippines, Diliman Abstract This study seeks to offer insight into the paradox between two ideologies that are currently being promoted in Philippine society and identify the relationship of both towards the indigenous community of the Ifugao in the country. Inclusion is a growing trend in many areas, such as education, business, and development. However, there is ambiguity in terms of educating and promoting inclusion for indigenous groups, particularly in the Philippines. Mandates to promote cultural preservation also present limits to the ability of indigenous people to partake in the cultures of mainstream society. The Ifugao, together with other indigenous tribes in the Philippines, are at a state of disadvantage due to the discrepancies between the rights that they receive relative to the more urbanized areas of the country. The desire to preserve the Ifugao culture and to become inclusive in delivering equal rights and services create divided vantages that seem to present a rift and dilemma deciding which ideology to promulgate. Apart from these imbalances, the stance of the Ifugao regarding this matter is unclear, particularly if they observe and follow a central principle. Given that the notion of inclusion is to accommodate everyone regardless of “race, gender, disability, ethnicity, social class, and religion,” it is highly imperative to provide clarity to this issue and identify what actions to take. -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Life is struggle, sacrifice, and worthy. On the other side, the people say that life means study or effort. People must struggle their right and obligation too. The struggling, sacrificing, and affording are one of requisites for acquiring their appreciations, dreams, and aims. The appreciation is the last destination that is brought into reality by the people. So everyone needs appreciation in their life. The appreciation is like a dream, goal or destination. It is a soul in proving something done by people. Appreciation can give the spirit and energy for someone in reaching their aim in their life. Many people that have acquired appreciation, they would be proud and satisfy both for themselves and another people in surrounding. However, sometimes the people have wrong ways to prove their appreciations. Appreciation need includes self actualization of human needs. Self actualization is one fundamental need in humanistic psychological theory. This need is part of hierarchy need in humanistic psychological theory. Humanistic psychology views humans as active creature with freedom. Abraham Maslow had explained the humanistic analysis in the psychological theory. The theory of Maslow is the hierarchy of needs that are the 1 2 psychological needs, safety needs, love and belonging needs and esteem needs. The four points above is the deficient needs or the basic needs. Maslow next had explained the growth needs as a motivation of human. The growth needs include self actualization (Clearer perception of reality, Acceptance of self, Other and nature, Spontaneity, Problem-centering, Detachment and the need for solitude, Autonomy, Independent of culture and environment, Continued fresher of appreciation, The mystic experience, the oceanic feeling, Oneness with humanity, Deep interpersonal relations, Democratic character structure, Ethical means towards moral ands, Philosophical, Creativeness). -

Bollywood As National(Ist) Cinema Violence, Patriotism and the National- Popular in Rang De Basanti

Third Text, Vol. 23, Issue 6, November, 2009, 703–716 Bollywood as National(ist) Cinema Violence, Patriotism and the National- Popular in Rang De Basanti Neelam Srivastava This essay sets out to explore the relationship between violence, patrio- tism and the national-popular within the medium of film by examining the Indian film-maker Rakeysh Mehra’s recent Bollywood hit, Rang de Basanti (Paint It Saffron, 2006). The film can be seen to form part of a body of work that constructs and represents violence as integral to the emergence of a national identity, or rather, its recuperation. Rang de Basanti is significant in contemporary Indian film production for the enormous resonance it had among South Asian middle-class youth, both in India and in the diaspora. It rewrites, or rather restages, Indian nationalist history not in the customary pacifist Gandhian vein, but in the mode of martyrdom and armed struggle. It represents a more ‘masculine’ version of the nationalist narrative for its contemporary audiences, by retelling the story of the Punjabi revolutionary Bhagat Singh as an Indian hero and as an example for today’s generation. This essay argues that its recuperation of a violent anti-colonial history is, in fact, integral to the middle-class ethos of the film, presenting the viewers with a bourgeois nationalism of immediate and timely appeal, coupled with an accessible (and politically acceptable) social activism. As the 1. Quoted in Namrata Joshi, sociologist Ranjini Majumdar noted, ‘the film successfully fuels the ‘My Yellow Icon’, Outlook middle-class fantasy of corruption being the only problem of the coun- India, online edition, 20 1 February 2006, available try’. -

The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

THE HINDU, THE MUSLIM, AND THE BORDER IN NATIONALIST SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA Vinay Lal University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There is but no question that we can speak about the emergence of the (usually Pakistani or Muslim) ‘terrorist’ figure in many Bollywood films, and likewise there is the indisputable fact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the political and public sphere. Indian cinema, however, may also be viewed in the backdrop of political developments in Pakistan, where the project of Islamicization can be dated to least the late 1970s and where the turn to a Wahhabi-inspired version of Islam is unmistakable. I argue that the recent history of Pa- kistan must be seen as instigated by a disavowal of the country’s Indic self, and similarly I suggest that scholarly and popular studies of the ‘representation’ of the Muslim in “Bol- lywood” rather too easily assume that such a figure is always the product of caricature and stereotyping. But the border between Pakistan and India, between the self and the other, and the Hindu and the Muslim is rather more porous than we have imagined, and I close with hints at what it means to both retain and subvert the border. Keywords: Border, Communalism, Indian cinema, Nationalism, Pakistan, Partition, Veer-Zaara Resumen 103 Así como el personaje del ‘terrorista’ (generalmente musulmán o paquistaní) está presente en muchos filmes de Bollywood, el nacionalismo hindú está tomando la iniciativa en la esfera política del país. Sin embargo el cine indio también puede hacerse eco de acontecimientos ocurridos en Paquistán, donde desde los años Setenta se ha manifestado un proceso de islamización de la sociedad, con una indudable impronta wahabí. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Regional Language Books

March 2011 Regional Language Books BENGALI 1 Banerjee, Mamata Aandolaner katha / Mamata Banerjee.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 191p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0922-2. B 080 MAM-aan C68922 2 Ahmed, Afsar Jiban jude prahar / Afsar Ahmed.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 192p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0875-1. B 891.443 AHM-j C68920 3 Basu, Nabakumar Achhe se nayantaray / Nabakumar Basu.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 184p.; 22cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0870-6. B 891.443 BAS-ac C68921 4 Chakravarti, Smaranjeet Aamader sei shahore / Smaranjeet Chakrabarti.-- Kolkata: Ananda Publications, 2009. 135p.; 22cm. ISBN : 978-81-7756-778-6. B 891.443 CHA-aam C68784 5 Giri, Bhagyadhar Aranye jhar othe / Bhagyadhar Giri.-- Kolkata: Supreme Publishers, 2008. 152p.; 21cm. B 891.443 GIR-ar C68805 6 Maity, Chittaranjan Nirjane khela / Chittaranjan Maity.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 368p.; 24cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0878-2. B 891.44308 MAI-n C68919 7 Indramitra Nerikutta / Indramitra.-- Kolkata: Karukatha, 2008. 108p.; 22cm. B 891.4431 IND-n C68697 8 Mitra, Premendra Bhoot-shikari mejokarta ebong / Premendra Mitra.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 199p.; 24cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0901-7. B 891.4431 MIT-b C68917 9 Maitra, Swapan Kabi Kishorimohan: jiban-o-kabya / Swapan Maitra.-- Kolkata: Manan Prakashan, 2008. 80p.; 21cm. B 928.9144 KIS-m C68918 GUJARATI 10 Valles, Father Dharmamangal / Father Valles.-- Ahmedabad: Gurjar Grantha Ratna Karyalaya, 2009. 240p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-8480-231-3. G 181.4 P9 B193600 11 Muni Vatsalydeep Jain dharma / Muni Vatsalydeep.-- Ahmedabad: Gurjar Grantharatna Karyalaya, 2008. -

Nawazuddin Siddiqui

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1, 2015 Music & Movies Nawazuddin Siddiqui, farmer’s son turned ‘Hindi indie’ star t is a story worthy of a Bollywood plot: The son of a selected for the Cannes Film Festival, he turned heads in cinema hall to watch his films. north Indian farmer, one of nine children, rising to crime thrillers “Kahaani” (Story) and “Talaash” (Search). He will appear again with Salman Khan in upcoming Ibecome the face of independent Hindi cinema. But He said his family are still surprised by how far he has romantic drama “Bajrangi Bhaijaan”, and with Shah Rukh Nawazuddin Siddiqui is still getting used to his success. come. “And you cannot blame them. I am a five-foot six- Khan in “Raees” (Rich Man), in which he plays a cop who “When someone is looking at me, I feel they are looking inch, dark, ordinary-looking man. People didn’t imagine is chasing Khan’s mafia character. Siddiqui says he at someone standing behind me, not at me,” the 40-year- that I would make it,” he said. “It is the mindset of our admires Bollywood megastars for their longevity- old confessed to AFP during an interview at a Mumbai country too, that people like (me) don’t become stars. ”they’re very well-maintained”-and he wouldn’t rule out hotel. Maybe it’s a result of 200 years of colonial rule.” doing a song-and-dance number himself, despite his “I have not got used to it and I won’t allow myself to Industry outsider reservations about Bollywood musicals. -

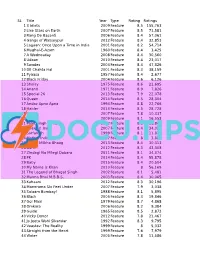

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

The Philippines Northern Highlights & Bohol Beach Stay 14 Days / 13 Nights

THE PHILIPPINES NORTHERN HIGHLIGHTS & BOHOL BEACH STAY 14 DAYS / 13 NIGHTS 14 DAYS 13 NIGHTS MANILA - NORTHERN ROUNDTRIP - BOHOL 2019-2020 Ever wonder where this masterpiece of nature is? This is Banaue, located on the mountains of the Philippine Cordillera, a place in the north of the Philippines famous for its rice terraces. Yes the Philippines consist of thousands of islands but you can also find mountains and elevated landscapes. After discovering the local villages, the natural wonders, and the hanging coffins of Sagada, a relaxing beach stay to end your stay makes for a perfect holiday! www.bluehorizons.travel Page 1 of 6 ITINERARY DAY 1 MANILA Arrive in Manila. You will be met and transferred to your hotel. Check in and overnight. Accommodation: 2 nights in Manila DAY 2 MANILA Meet our Tour Representative at the lobby of your hotel for your Exploring Old Manila Tour. The city of Manila is bisected by Pasig River, a tidal estuary that connects Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay. On its southern banks is the city center, where government and private offices, schools, shopping malls and manmade historical landmarks are located; on its northern edge are the densely populated, working class districts such as Quiapo, Binondo and Escolta, which used to be the city’s commercial district during the Spanish colonial period. Traversing from south to north, the tour affords one a glimpse of Manila’s colonial past and its relevance in the present times. ‘Exploring Old Manila’ combines a visit to the main attractions of Intramuros, including Rizal Park. A ‘calesa’ ride (horse- drawn carriage) will take you to Chinatown in Binondo. -

The Lawu Languages

The Lawu languages: footprints along the Red River valley corridor Andrew Hsiu ([email protected]) https://sites.google.com/site/msealangs/ Center for Research in Computational Linguistics (CRCL), Bangkok, Thailand Draft published on December 30, 2017; revised on January 8, 2018 Abstract In this paper, Lawu (Yang 2012) and Awu (Lu & Lu 2011) are shown to be two geographically disjunct but related languages in Yunnan, China forming a previously unidentified sub-branch of Loloish (Ngwi). Both languages are located along the southwestern banks of the Red River. Additionally, Lewu, an extinct language in Jingdong County, may be related to Lawu, but this is far from certain due to the limited data. The possible genetic position of the unclassified Alu language in Lüchun County is also discussed, and my preliminary analysis of the highly limited Alu data shows that it is likely not a Lawu language. The Lawu (alternatively Lawoid or Lawoish) branch cannot be classified within any other known branch or subgroup or Loloish, and is tentatively considered to be an independent branch of Loloish. Further research on Lawu languages and surrounding under-documented languages would be highly promising, especially on various unidentified languages of Jinping County, southern Yunnan. Table of contents Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Lawu 3. Awu 4. Lewu Yao: a possible relative of Lawu 5. Alu: a Lalo language rather than a Lawu language 6. Conclusions 7. Final remarks: suggestions for future research References Appendix 1: Comparative word list of Awu, Lawu, and Proto-Lalo Appendix 2: Phrase list of Lewu Yao Appendix 3: Comparative word list of Yi lects of Lüchun County 1 1. -

I Stella M. Gran-O'donn

Being, Belonging, and Connecting: Filipino Youths’ Narratives of Place(s) and Wellbeing in Hawai′i Stella M. Gran-O’Donnell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Karina L. Walters, Chair Tessa A. Evans Campbell Lynne C. Manzo Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Social Work © Copyright 2016 Stella M. Gran-O’Donnell University of Washington Abstract Being, Belonging, and Connecting: Filipino Youths’ Narratives of Place(s) and Wellbeing in Hawai′i Stella M. Gran-O’Donnell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Karina L. Walters School of Social Work Background: Environmental climate change is an urgent concern for Pacific Islanders with significant impact on place along with bio-psycho-social-cultural-spiritual influences likely to affect communities’ wellbeing. Future generations will bear the burden. Indigenous scholars have begun to address climate-based place changes; however, immigrant Pacific Islander populations have been ignored. Although Filipinos are one of the fastest growing U.S. populations, the second largest immigrant group, and second largest ethnic group in Hawai’i, lack of understanding regarding their physical health and mental wellbeing remains, especially among youth. This dissertation addresses these gaps. In response to Kemp’s (2011) and Jack’s (2010, 2015) impassioned calls for the social work profession to advance place research among vulnerable populations, this qualitative study examined Filipino youths’ (15-23) experiences of place(s) and geographic environment(s) in Hawai′i. Drawing on Indigenous worldviews, this study examined how youth narrate their sense of place, place attachments, ethnic/cultural identity/ies, belonging, connectedness to ancestral (Philippines) and contemporary homelands (Hawai’i), virtual environment(s), and how these places connect to wellbeing.