Final Dissertaion BUKA.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue Number 1, 2016

Issue Number 1, 2016 A sub-regional UNESCO-ICH project Supported by the Flanders Government SAICH NEWS Senior officials, consultants and coordinators of the SAICH Platform Prof. David J. Simbi Mr. Damir Dijakovic Dr. Thokozile Chitepo Vice Chancellor, Regional Cultural Advisor, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Rural Development, Promotion and Preservation Chinhoyi University of UNESCO Regional Office of National Cultural Heritage, Zimbabwe Technology for Southern Africa Mr. Stephen Chifunyise Dr. Marc Jacobs Mr. Lovemore Mazibuko UNESCO ICH Expert/ UNESCO ICH Expert/ UNESCO ICH Expert/ Consultant Flanders Government Consultant Representative Prof. Herbert Chimhundu Prof. Jacob Mapara Dr. Manase K. Chiweshe Coordinator Associate Coordinator Associate Coordinator SAICH Platform SAICH Platform SAICH Platform Editor-in-Chief Cover Page Professor Herbert Chimhundu Event: Great Limpopo Cultural Trade Fair, Location: Boli Muhlanguleni, Editor Chiredzi, Zimbabwe, Photograph by: Mr. Eugene Ncube Professor Jacob Mapara Contacts Contributors SAICH Platform Dr Manase K. Chiweshe Chinhoyi University of Technology Ms Varaidzo Chinokwetu P. Bag 7724, Ms Jacqueline Tanhara Chinhoyi Design Off Harare-Kariba Highway Mr. Eugene Ncube Zimbabwe Printing Telephone: +2636727496 CUT Printing Press E-mail: [email protected] | [email protected] SAICH NEWS SAFEGUARDING SAICH NEWS Participating Countries ParticipatingParticipating Countries Countries Participating Countries ParticipatingParticipatingParticipating CountriesCountries Countries BotswanaParticipatingBotswana -

MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY APPROVAL FORM The

MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have supervised, read and recommend to the Midlands State University for acceptance of dissertation entitled: Violation of Children `s rights by Varemba cultural practise in Mberengwa District 1980-2013 submitted by Nokuthula Bula-Bula in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History and International studies Honours Degree Signature of Student........................................................................................................................... Signature of Supervisor...................................................................................................................... Signature of the Chairperson............................................................................................................. Signature of the Examiner(s)............................................................................................................. 1 DECLARATION I, Bula-bula Nokuthula (R103446R), certify that this dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Bachelor of Arts honours degree in History and International Studies at Midlands State University has not been submitted for a degree at any other University, and that it is entirely my work. Student’s name Nokuthula.L Bula-Bula Signature ……………………………… Date ........../......../............ 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank the almightys God who gave me the wisdom and knowledge to accomplish the work. My appreciation is -

Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital

Province District Name of Site Bulawayo Bulawayo City E. F. Watson Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital Bulawayo Bulawayo City Nkulumane Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City United Bulawayo Hospital Manicaland Buhera Birchenough Bridge Hospital Manicaland Buhera Murambinda Mission Hospital Manicaland Chipinge Chipinge District Hospital Manicaland Makoni Rusape District Hospital Manicaland Mutare Mutare Provincial Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Bonda Mission Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Hauna District Hospital Harare Chitungwiza Chitungwiza Central Hospital Harare Chitungwiza CITIMED Clinic Masvingo Chiredzi Chikombedzi Mission Hospital Masvingo Chiredzi Chiredzi District Hospital Masvingo Chivi Chivi District Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chimombe Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chinyika Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chitando Rural Health Centre Masvingo Gutu Gutu Mission Hospital Masvingo Gutu Gutu Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Mukaro Mission Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Masvingo Provincial Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Morgenster Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Matibi Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Neshuro District Hospital Masvingo Zaka Musiso Mission Hospital Masvingo Zaka Ndanga District Hospital Matabeleland South Beitbridge Beitbridge District Hospital Matabeleland South Gwanda Gwanda Provincial Hospital Matabeleland South Insiza Filabusi District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe Plumtree District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe St Annes Mission Hospital (Brunapeg) Matabeleland South Matobo Maphisa District Hospital Matabeleland South Umzingwane Esigodini District Hospital Midlands Gokwe South Gokwe South District Hospital Midlands Gweru Gweru Provincial Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Kwekwe General Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Silobela District Hospital Midlands Mberengwa Mberengwa District Hospital . -

The Food Poverty Atlas

Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page 1 The Food Poverty Atlas SMALL AREA FOOD POVERTY ESTIMATION Statistics for addressing food and nutrition insecurity in Zimbabwe SEPTEMBER, 2016 Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page 2 2 Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page i The Food Poverty Atlas SMALL AREA FOOD POVERTY ESTIMATION Statistics for addressing food and nutrition insecurity in Zimbabwe SEPTEMBER, 2016 i Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page ii © UNICEF Zimbabwe, The World Bank and Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency 20th Floor, Kaguvi Building, Cnr 4th Street and Central Avenue, Harare, Zimbabwe P.O. Box CY342, Causeway, Harare, Zimbabwe. Tel: (+263-4) 706681/8 or (+263-4) 703971/7 Fax: (+263-4) 762494 E-mail: [email protected] This publication is available on the following websites: www.unicef.org/zimbabwe www.worldbank.org/ www.zimstat.co.zw/ ISBN: 978-92-806-4824-9 The Food Poverty Atlas was produced by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). Technical and financial support was provided by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Bank Design and layout: K. Moodie Photographs by: © UNICEF/2015/T. Mukwazhi ii Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page iii Food poverty prevalence at a glance Map 1: Food poverty prevalence by district* Figure 1 400,000 Number of food poor 350,000 and non poor households 300,000 250,000 by province* 200,000 150,000 100,000 50,000 0 Harare Central N.B 1. -

Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012

Zimbabwe Provincial Report Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012 Population Census Office P.O. Box CY342 Causeway Harare Tel: 04-793971-2 04-794756 E-mail: [email protected] Census Results for Midlands Province at a Glance Population Size Total 1 614 941 Males 776 787 Females 838 154 Annual Average Increase (Growth Rate) 2.2 Average Household Size 4.5 1 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents...............................................................................................................................3 List of Tables.....................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................9 Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................10 Midlands Fact Sheet (Final Results) .................................................................................................13 Chapter 1: ........................................................................................................................................14 Population Size and Structure .......................................................................................................14 Chapter 2: ........................................................................................................................................24 Population Distribution -

Zimbabwe Page 1 of 35

Zimbabwe Page 1 of 35 Zimbabwe Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2001 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 4, 2002 Zimbabwe is a republic in which President Robert Mugabe and his Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) have dominated the executive and legislative branches of the Government since independence in 1980. Although the Constitution allows for multiple parties, opposition parties and their supporters were subjected to significant intimidation and violence by the ruling party and government security forces, and financial restrictions continued to be imposed on the opposition. The 2000 parliamentary elections were preceded by a government-sanctioned campaign of violence directed towards supporters and potential supporters of the opposition. Although most election observers agreed that the voting process itself generally was peaceful, there were irregularities. In 1999 the country's first viable opposition party emerged, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which won 57 out of 120 seats in the June 2000 parliamentary elections. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary, and in practice the judiciary remained largely independent despite government attempts to dilute its independence; however, the Government repeatedly refused to abide by judicial decisions. The Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) is responsible for maintaining law and order. Although the ZRP officially is under the authority of the Ministry of Home Affairs, in practice it is controlled by the President's office. The Zimbabwe National Army and Air Force under the Defense Ministry are responsible for external security; however, they frequently were called upon for domestic operations during the year. The Central Intelligence Organization (CIO), under the Minister of State for National Security in the President's Office, is responsible for internal and external security, but it does not have powers of arrest. -

DAILY CHOLERA UPDATE and ALERTS 17Th January, 2009 ***Completeness of Reporting Updated

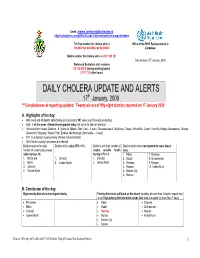

Email: [email protected] http://ochaonline.un.org/Default.aspx?alias=ochaonline.un.org/zimbabwe Toll free number for cholera alert is Office of the WHO Representative in 08089001 or 08089002 or 08089000 Zimbabwe Mobile number for cholera alerts is 0912 104 257 Date of issue:18th January, 2008 Water and Sanitation alert numbers 04 703 941-2 (during working hours) 2 917 710 (after hours) DAILY CHOLERA UPDATE AND ALERTS 17th January, 2009 ***Completeness of reporting updated. Twenty-six out of fifty-eight districts reported on 17 January 2009 A. Highlights of the day: • 650 cases and 45 deaths added today (in comparison 997 cases and 65 deaths yesterday) • 44.8 % of the areas affected have reported today (26 out of 58 affected districts) • 39 cases from Harare (Budiriro - 8, Mabvuku, Mbare, Glen View – 4 each, Dzivarasekwa-3, Mufakose, Tafara, Whitecliffe -2 each, Hatcliffe, Hopley, Kuwadzana, Grange, Greencroft, Westgate, Warren Park, Eastlea, Marlborough, Borrowdale – 1 each) • 87.1 % of districts reported to be affected (54 districts/62) • All 10 of the country's provinces are affected Districts reported an high Districts with a daily CFR > 5% : Districts with high number of Districts which have not reported for more than 3 number of cases today (cases deaths outside health days: added today> 30) facility/ CTC > 3 1. Mbire 7. Chipinge 1. Mt Darwin 1. Chiredzi 1. Chiredzi 2. Mudzi 8. Chimanimani 2. Bikita 2. Gokwe North 2. Gokwe North 3. Hwedza 9. Nyanga 3. Chiredzi 4. Mutasa 10. Kariba Rural 4. Gokwe North 5. Mutare City 6. Buhera B. -

Zimbabwean Government Gazette

l4 ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. LXYII, No. 12 3rd MARCH. 1989 Price 40c General Notice 94 of 1989. Mhondoro Express (Pvt.) Ltd. 0/401/88. Permit: 24129. Motor-omnibus. Passenger-capa ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ACT [CHAPTER 262] city: 76. Route: Harare - Norton - Chegutu - Kadoma - Kwekwe - Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits Gweru - Shangani - Insiza - Bulawayo. By: Alteration to rimning times. IN tarns of subsection (4) of section 7 of the Road Motor Transportation Act [Chafer 262], notice is hereby given that The service operates as follows— the applications detailed in the Sdiedule, for the issue or (a) depart Harare Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday amendment of road service permits, have been received for the 6.30 a.m., arrive Bulawayo 1.45 p.m.; consideration of the Controller of Road Motor Transportation. -(5) depart Bulawayo Wednesday and Friday 8 a.m., arrive Any p ^o n wishing to object to any such atqjlication must Harare 3.15 p.m.; lodge with the Cmrtroller of Road Motor Transportation, (c) depart Bulawayo Sunday 12 noon, arrive Harare P.O. Box 8332, Causeway— 7.15 p.m. (a) a notice, in writing of his intention to object, so as to reach the Controller’s olBce not later than the 24th The service to operate as follows— March, 1989; (a) depart Harare Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday (b) his objection and the grounds therefor, on form R.M.T. 6.30 a.m., arrive Bulawayo 12.40 p.m.; 24, toother with two copies thereof, so as to reach the (b) depart Bulawayo Wednesday and Friday 8 a.m., arrive Controller’s office not later than the 14th April, 1989. -

Zimbabwe: Insight Into the Humanitarian Crisis and Food Politics

Study report • r a p p o r t d ' é t u d e www.actioncontrelafaim.org www.actioncontrelafaim.ca Zimbabwe: insight into the humanitarian crisis www.accioncontraelhambre.org and food politics January 2006 www.aah-usa.org www.aahuk.org Contact: Anne Garella & + 33 1 43 35 88 62 [email protected] Zimbabwe: insight into the humanitarian crisis and food politics January 2006 Zimbabwe: insight into the humanitarian crisis and food politics ON I E x E c u t i v E S u m m a r y a n d r E c o m m E n d a t i o n S NTRODUCT I n 2002-03, Zimbabwe was the epicentre of and a high prevalence of HIV/AIDS. Yet, Zimbabwe the so-called Southern Africa ‘food crisis’ has faced a very unique situation over the past few Iwith over six million people declared in years: the land reform and the resulting tense rela- need of emergency food aid. The crisis was tions with some western countries have not only triggered by a drought and compounded by the influenced the causes of the crisis but also shaped consequences of the economic decline, notably the way responses have been provided. the poor availability and high prices of agricultural inputs. The Fast Track land reform programme The human rights violations and political tensions started in 2000 also greatly contributed to the crisis, around the land reform have often obliterated the by reducing food production and compounding fact that a meaningful land redistribution, accompa- economical difficulties. -

The History of the Mining Industry in Mberengwa 1890-2014

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY The history of the mining industry in Mberengwa 1890-2014 By Gumbo Nyashadzashe R111940J Supervisor: Mr. G Tarugarira Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History Honours Degree in the Department of History November 2014 Approval form The undersigned certify that they have read and recommend to Midlands State University for acceptance, a research project entitled: The History of the Mining Industry in Mberengwa 1890-2014Submitted by Gumbo Nyashadzashe in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Arts in History Honors Degree. ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------ SUPERVISOR DATE ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------ CHAIRPERSON DATE i Table of contents Approval form ....................................................................................................................... Release form ....................................................................................................................... v Declaration form ................................................................................................................ vi Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... vii Dedication ........................................................................................................................ viii List of acronyms ............................................................................................................... -

Local Government Reform in Zimbabwe a Policy Dialogue

Local government reform in Zimbabwe A policy dialogue Edited by Jaap de Visser, Nico Steytler and Naison Machingauta State, Peace and Human Security Studies Local government reform in Zimbabwe A policy dialogue Edited by Jaap de Visser, Nico Steytler and Naison Machingauta Community Law Centre 2010 PB | Local government reform in Zimbabwe: A policy dialogue The State, Peace and Human Security Programme of the Community Law Centre (University of the Western Cape) conducts research and provides policy advice on state efficiency, human security and peace building in Africa. It focuses on the role of decentralisation and federalism in enhancing the efficiency of African states, in building sustainable peace in post-conflict regions and improving human security on the continent. It does this through doctoral research programmes, a Masters Programme, applied research and policy advice to governments. State, Peace and Human Security Studies is a series containing the results of applied research conducted by local experts. Community Law Centre University of the Western Cape Modderdam Road Bellville 7535 South Africa +27 21 959 2950 [email protected] © 2010 Community Law Centre (University of the Western Cape). No part hereof may be reproduced without the written consent of the Centre. ISBN: 978-1-86808-708-2 Design and layout: Page Arts cc Printed by Mega Digital Cover photograph of Samora Machel Road, Harare: Annette May Financial support was provided by the Interchurch Organisation for Development Cooperation, the Austrian Development Cooperation (through the Gemeinnuetzige Entwicklingszusammenarbeit GMbH) and the Ford Foundation. Austrian Development Cooperation iii ii Local authorities and traditional leadership: John Makumbe | Contents Foreword v Opening speech ix Abstracts xiii Chapter 1: Can local government steer socio-economic transformation in Zimbabwe? Analysing historical trends and gazing into the future 1 Kudzai Chatiza 1. -

Government Gazette |

| - GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority > Vol. LXIV, No. 46 29th AUGUST,1986 Price 40c Genéral Notice 584 of 1986. F, Pullen. a ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ACT [CHAPTER 262] O/511/86. Motor-omnibus. Passenger-capacity: 76. ‘Route: Hwange - Dete - Kamative - Pashu - Lubu Turn-off - . Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits Lubu - Binga District Council. The service to operate as follows— IN terms of subsection (4) of section 7 of the Road Motor (a) depart Hwange Monday, Wednesday dnd Saturday Transportation Act [Chapter 262], notice is hereby given that 8 a.m., arrive Binga District Council 12.20 p.m.; . ‘the applications detailed in the Schedule, for the issue or (b) depart Hwange Friday 5 p.m., arrive Binga District amendment of road service permits, have been received for Council 9.20 p.m.; Motor Transporta- the consideration of the Controller of Road - (e) depart Binga District Council Tuesday and Thursday tion, 8 a.m., arrive Hwange 12.20 p.m; Any person wishing to object to any such application must (d) depart Binga District Council Saturday 1 a.m., arrive lodge with the Controller of Road Motor ‘Transportation, Hwange 5.20 a.m; P.O. Box 8332, Causeway— (©) depart Binga District Council Sunday 9 am., arrive LOPWAIRaB!, (a) a notice, in writing, of his intention to object, so as to Hwange 1.20 p.m. ‘reach the Controller’s office not later than the 19th September, 1986; . t/a Moyomuchena Buses. : . oe -| B. Mabodza, _(b) his objection and the grounds therefor, on form R.M.T. 0/674/86.