Discussion Paper 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

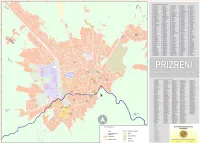

Map Data from the City of Prizren For

1 E E 3 <*- * <S V to v-v % X % 5.- ^s RADHITJA E EMRAVE SIPAS ALFABETIT -> 42 8 Marsi-7D 443 Brigáda 126-4C 347 Hysen Rexhepi-6E7E 253 Milan Šuflai-3H 218 Shaip Zurnaxhiu-4F 187 Abdy Beqiri-4E 441 Brigáda 128- 234 Hysen Trpeza-2E H 356 Mimar Sinan-6E 133 Shat Kulla-6E 1 Adem Jasharí-6E,5F 20 Bubulina-1A 451 Hysni Morína-3B 467 Mojsi Golemi-2A, 2B 424 Shefqet Berisha-80 | 360 Adnan Krasniqi-7E 97 Bujana-2D 46 Hysni Temaj- 25 Molla e Kuqe 390 Sheh Emini-7D 310 Adriatiku-5F 327 Bujar Godeni-6E 127 Ibrahim Lutfiu-6D 72 Mon Karavidaj-3C3D 341 Shn Albani-7F 38 Afrim Bytygi-1B,2B 358 Bujtinat-6E, 7E 259 Ibrahim ThagiSH 184 Morava-4E \J336 Shn Flori-6F, 7F 473 Afrim Krasniqi-9C 406 Burími-8D 45 Idriz Behluli- 23 Mreti Gllauk-1A \~345 Shn Jeronimi 1 444 Afrim Stajku-4C 261 Bushatlinjt-2H 39 llir Hoxha-1B 265 Muhamet Cami~3H 284 SherifAg TurtullaSG 446 Agim Bajrami-4C 140 Byrhan Shporta-6D 233 llirt-2E 21 Muhamet Kabashi-1A 29 Shestani | 278 Agim ShalaSF 47 Camilj Siharic 359 lljaz Kuka-6E,7E 251 Muharrem Bajraktarí-2H,3E 243 Shime Deshpali-2E 194 Agron Bytyqi-4E 56 Cesk Zadeja-3C 381 Indrit Cara -Kavaja-6D, 7D 74 Muharrem Hoxhaj-3C 291 Shkelzen DragajSF 314 Ahmet KorenicaSF 262 Dalmatt-3H 86 Isa Boletini-4D 458 Muharrem Samahoda-3B 199 Shkodra-3E \~286 293 Ahmet KrasniqiSF 475 Dardant-9C Islám Spahiu-5G l 316 MuhaxhirtSF \428 Shkronjat-7C, 7D 207 \Ahmet Prístina-5F4F 5 De Rada-6D, 5D \~7 Ismail Kryeziu-5D,4D 60 Mujo Ulqinaku-3C 138 Shote Galica-6D 447 Ajahidet-4C 61 Dd Gjon Luli-3C 40 Ismail Qemali-2B 1 69 Murat Kab ashi-4F, 5E 392 Shpend Berisha-7E -

Albania Pocket Guide

museums albania pocket guide your’s to discover Albania theme guides Museums WELCOME TO ALBANIA 4 National Historic Museum was inaugurated on 28 October 1981. It is the biggest Albanian museum institution. There are 4750 objects inside the museum. Striking is the Antiquity Pavilion starting from the Paleolithic Period to the Late Antiquity, in the 4th century A.D., with almost 400 first class objects. The Middle Age Pavilion, with almost 300 objects, documents clearly the historical trans- formation process of the ancient Illyrians into early Arbers. CONTENTS i 5 TIRANA 6 DURRES 14 ELBASAN 18 LUSHNJE 20 KRUJE 20 APOLLONIA 26 VLORA 30 KORÇA 34 GJIROKASTRA 40 BERATI 42 BUTRINTI 46 LEZHE 50 SHKODER 52 DIBER 60 NATIONAL HISTORIC MUSEUMS TIRANA 6 National Historic Museum was inaugurated on 28 October 1981. It is the biggest Albanian museum institution. Pavilion starting from the Paleolithic Period to the Late Antiquity, in the 4th century A.D., with almost 400 first class objects. The Middle Age Pavilion, with almost 300 objects, documents clearly the historical transformation process of the ancient Illyrians into early Arbers. This pavilion reflects the Albanian history until the 15th century. Other pavilions are those of National Renaissance, Independence and Albanian State Foundation, until 1924. The Genocide Pavilion with 136 objects was founded in 1996. The Iconography Pavilion with 65 first class icons was established in 1999. The best works of 18th and 19th century painters are found here, like Onufër Qiprioti, Joan Çetiri, Kostandin Jermonaku, Joan Athanasi, Kostandin Shpataraku, Mihal Anagnosti and some un- known authors. In 2004 the Antifascism Pavilion 220 objects was reestablished. -

European Union Election Expert Mission Kosovo 2021 Final Report

European Union Election Expert Mission Kosovo 2021 Final Report Early Legislative Elections 14 February 2021 The Election Expert Missions are independent from the institutions of the European Union. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy and position of the European Union. European Union Election Expert Mission Kosovo* Early Legislative Elections – 14th February 2021 Final report I. SUMMARY Elections were held for the 120-member unicameral Kosovo Assembly on 14th February 2021. As with the four previous legislative elections since Kosovo’s 2008 declaration of independence, these were early elections provoked by a political crisis. The elections were competitive, and campaign freedoms were generally respected. There was a vibrant campaign, except in the Kosovo Serb areas. Despite a very short timeframe and challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Central Election Commission (CEC) administered the elections well and in a transparent manner, although problems with Out of Kosovo voting reduced confidence in that part of the process. Election day was assessed by local observers as orderly, with voters participating in high numbers. However, as with previous elections, the process deteriorated during the vote count and a large number of recounts were ordered due to discrepancies in the results protocols. Such long-standing systemic problems, which have been identified in previous EU EOMs, should be addressed to enable Kosovo to fully meet international standards for democratic elections. These elections were held in an increasingly polarised atmosphere, influenced by the turbulent political developments since the last legislative elections. -

Gjoka Konstruksion

143 www.rrugaearberit.com GAZETË E PAVARUR. NR. 3 / 2018. ÇMIMI: 50 LEKË. 20 DENARË. 1.5 EURO. Intervistë Art Profil Dr. Ahmet Alliu, Bajram Mata zgjodhi Pajtim Beça, një mjeku i parë i Dibrës të jetojë me fjalën e histori suksesi në Historiku i shërbimit shëndetësor në veprat e realizuara breg të Drinit optikën e mjekut të parë dibran Nga prof.as.dr.Nazmi KOÇI 16 Nga Selami NAZIFI 12 Nga Osman XHILI 9 NË BRENDËSI: Rruga e Arbrit: Qeveria firmos kontratën, Jemi skeptike për aq kohë sa nuk ka transparencë për fondet dhe projektin “Gjoka Konstruksion” gati të nisë punën Rruga e Arbrit i bashkon shqiptarët Dhjetë arsye përse duhet vizituar Dibra Rafting lumenjve të Dibrës që s’bëzajnë “FERRA E PASHËS” Jashar Bunguri, gjeneral i bujqësisë shqiptare Kastrioti, fshati pa Kastriotë Asllan Keta: Më shumë se Partinë, dua Shqipërinë Tenori Gerald Murrja: Ëndrra ime është të këndoj në skenat e operave në botë Shkolla Pedagogjike e Peshkopisë, tempull i dijes dhe edukimit Mustafa Shehu, një zemër Lexoni në faqen 2 që skaliti me zjarr emrin e tij në histori REPORTAZH SPORT: Alia dhe Halili, dy dibranët e Kombëtares U-19 Fadil Shulku, portieri modern i kohës Cerjani, një fshat Drini Halili:Objektivi është Kombëtarja!. Shqiponja dibrane i braktisur dhe i Marko Alia: Mes Italisë dhe Shqipërisë zgjodha vendin tim! Njerëz që hynë dhe mbetën në kujtesën e dibranëve rrënuar nga migrimi Islamil Hida, njeri i edukuar, fjalëpak e punëshumë Më shumë mund të shikoni në faqen e gazetës Nga BESNIK LAMI në FB: Rruga e Arbërit ose ndiq linkun: https://tinyurl.com/lcc3e2f erjani është një nga katër fshatrat e zonës së CBellovës që shtrihet në verilindje të qytetit të Peshkopisë, rreth 7 km larg tij. -

Flori Bruqi Konti I Letrave Shqipe

Përgatiti: Dibran Fylli Naim Kelmendi FLORI BRUQI KONTI I LETRAVE SHQIPE (Intervista, vështrime, recensione) AKADEMIA SHQIPTARO-AMERIKANE THE ALBANIAN AMERICAN ACADEMY E SHKENCAVE DHE ARTEVE OF SCIENCE AND ARTS NEW YORK, PRISHTINË, TIRANË, SHKUP Shtëpia botuese “Press Liberty” Për botuesin Asllan Qyqalla Redaktor gjuhësor Naim Kelmendi Recensent Zef Pergega Kopertina-dizajni Dibran Fylli Radhitja kompjuterike dhe faqosja uniART Creative © të gjitha të drejtat (f.b) Dibran Fylli Naim Kelmendi FLORI BRUQI KONTI I LETRAVE SHQIPE (Intervista, vështrime, recensione) PRESS LIBERTY Prishtinë 2021 Shkrime kritike nga: Zef Pergega, Eshref Ymeri, Namik Shehu, Naim Kelmendi, Kujtim Mateli,Rushit Ramabaja, Reshat Sahitaj, Fatmir Terziu, Mehmet Kajtazi, Iljaz Prokshi, Lumturie Haxhiaj, Dibran Fylli, Rrustem Geci, Kristaq Shabani, Faik Xhani, Rasim Bebo, Rexhep Shahu, Nijazi Halili, Adem Avdia, Bajame Hoxha... Flori Bruqi-Konti i letrave shqipe PIKËPAMJE PËR KRJIMTARINË LETRARE, KRITIKËN DHE KRIZËN E IDENTITETIT Intervistë e gjatë me shkrimtarin Flori Bruqi Nga Akademik Prof.dr. Zef Përgega Atë që nuk e bëri shteti e bëri njeriu, Flori Bruqi, Konti i kulturës dhe letrave shqipe. Leksikoni pikë së pari është një leksion për Akademitë e Shkencave të Shqipërisë, Kosovës dhe trevave të tjera shqiptare. Flori Bruqi u ka ngritur njerë- zve një permendore të derdhur ne shkronja, i ka vlerësuar në motivin më të lartë që kurrë nuk do ta përjetonin nga shteti, të cilit i shërbyen me devocion, ashtu siç bënë çdo gjë për kombin e tyre. Gjëja më e keqe dhe e rëndomtë tek shqiptari është mungesa e kujtesës dhe e ndërimit, që prej tyre vjen bashkimi, ndërsa ato i mbajnë sytë e lumturohen në gardhin e lartë të ndarjes mes nesh, që po me paratë e popullit ndërton muret e ndarjes.Flori Bruqi është një etalon i paparë, një shpirt i madh që nuk kërkon lavd. -

Cv Petrit Halilaj

CV PETRIT HALILAJ Born in Kostërrc (Skenderaj-Kosovo) in 1986. Lives and works in Berlin. Residencies: 2014 Villa Romana, Florence 2013 Fürstenberg, Donaueschingen Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2015 Hangar Bicocca, curated by Roberta Tenconi, Milan ABETARE, curated by Moritz Wesseler and Carla Donauer, Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne She fully turning around became terrestrial, curated by Rein Wolfs, at Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn 2014 Yes but the sea is attached to the earth and it never floats around in space. The stars would turn off and what about my planet?, Kamel Mennour, Paris of course blue affects my way of shitting, Chert, Berlin Darling squeeze the button and remove my memory, Galeria e Arteve e Kosovës, Prishtina I’m hungry to keep you close. I want to find the words to resist but in the end there is a locked sphere. The funny thing is that you’re not here, nothing is, Kunshalle Lissabon, Lisbon 2013 July 14th?, Foundation d’Enterprise Galeries Lafayette, Paris I’m hungry to keep you close. I want to find the words to resist but in the end there is a locked sphere. The funny thing is that you’re not here, nothing is, Kosovo Pavillion, Venice Biennale, curated by Kathrin Rhomberg, commissioned by Erzen Shkololli, Arsenale, Venice Poisoned by men in need of some love, curated by Elena Filipovic, WIELS Contemporary Art Center, Brussels Petrit Halilaj, Tongewölbe T25, Ingolstadt 2012 Who does the earth belong to while painting the wind?!, curated by Giovanni Carmine, Kunsthalle Sankt Gallen, St. Gallen 2011 Petrit Halilaj, curated by Veit Loers, Kunstraum Innsbruck, Innsbruck Kostërrc (CH), Statements, Art Basel , with Chert, Berlin 2009 Back to the Future, curated by Albert Heta, Stacion, Center for Contemporary Art Prishtina, Kosovo. -

Kosovo After Haradinaj

KOSOVO AFTER HARADINAJ Europe Report N°163 – 26 May 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. THE RISK AND DEFLECTION OF REBELLION................................................... 2 A. MANAGEMENT OF THE HARADINAJ INDICTMENT ..................................................................2 B. SHADOW WARRIORS TEST THE WATER.................................................................................4 C. THE "WILD WEST" ON THE BRINK ........................................................................................6 D. DUKAGJINI TURNS IN ON ITSELF ...........................................................................................9 III. KOSOVO'S NEW POLITICAL CONFIGURATION.............................................. 12 A. THE SHAPE OF KOSOVO ALBANIAN POLITICS .....................................................................12 B. THE OCTOBER 2004 ELECTIONS .........................................................................................13 C. THE NETWORK CONSOLIDATES CONTROL ..........................................................................14 D. THE ECLIPSE OF THE PARTY OF WAR? ................................................................................16 E. TRANSCENDING OR DEEPENING WARTIME DIVISIONS?.......................................................20 IV. KOSOVO'S POLITICAL SYSTEM AND FINAL STATUS.................................. -

Download Here

Band 12 / 2018 Band 12 / 2018 The EU’s Western Balkan strategy is gaining a new and positive momentum. However, this development leads to the question how to deal with the challenges lying ahead for overcoming blockades and improving intra-state/neighbourhood relations in South East Europe. This general issue was comprehensively Overcoming Blockades and analysed by the Study Group “Regional Stability in South East Europe” at its 36th Workshop. Improving Intra-State Thus it appears that South East Europe, and especially the peace consolidating Western Balkans, seems to be at a decisive Neighbourhood Relations in South East Europe crossroads once again. This will either lead to the substantial improvement of intra-state and regional relations among future EU members or will prolong nationalistic, anti-democratic and exclusive policies, thereby harming also EU integration as the core consolidation tool in the Western Balkans. Overcoming Blockades and Improving Intra-State and Improving Blockades Overcoming ISBN: 978-3-903121-53-9 Predrag Jureković (Ed.) 12/18 36th Workshop of the PfP Consortium Study Group “Regional Stability in South East Europe” (Ed.) Jureković Study Group Information Study Group Information Predrag Jureković (Ed.) Overcoming Blockades and Improving Intra-State/ Neighbourhood Relations in South East Europe 36th Workshop of the PfP Consortium Study Group “Regional Stability in South East Europe” 12/2018 Vienna, September 2018 Imprint: Copyright, Production, Publisher: Republic of Austria / Federal Ministry of Defence Rossauer -

Serbia Kosovo

d ANALYSIS 03/04/2012 SERBIA - KOSOVO: A GLIMMER OF LIGHT AT THE END OF THE TUNNEL? By Lieutenant Colonel (ret.) Pierre ARNOLD ESISC Research Associate Finally! On 24 February 2012, Serbia and Kosovo succeeded in reaching their first overall agreement. The two adversaries have, for the first time, moved to the foreground their wish to emerge from their isolation and seize the chance of becoming Europeans (nearly) like everyone else. While nothing is firmly in place, the two governments, which have taken what are no doubt calculated risks vis-à-vis their public opinions, have given way to international pressure coming from many sources and have ended up taking the first step. Relations nevertheless still tense between Belgrade and Priština The year 2011 saw a succession of miscellaneous incidents, more or less serious, on the border between Kosovo and Serbia. When the post of Jarinje was vandalised, President Tadić essentially called attention to the action of persons aiming at putting the bilateral dialogue in question, while the Kosova Prime Minister spoke of ‘parallel Serb structures’1. The Serbian President avoided implicating his fellow citizens of Kosovo, knowing that he had only a rather narrow margin for manœuvre with them. In order to avoid in the future this type of attack, some observers suggested as the solution negotiations and assistance with legal commerce 2. These negotiations ended seven months later in results which no one expected any longer: a ‘semi-recognition’ by Belgrade of the existence of Kosovo. Meanwhile, Belgrade and Priština have understood that normalisation of trade between the two countries was without doubt the solution. -

The Political Landscape in Kosovo Since the Declaration of Independence

Südosteuropa 58 (2010), H. 1, S. 41-66 DEMOCRATIC VALUES AND ETHNIC POLARIZATION HILDE KATRINE HAUG The Political Landscape in Kosovo since the Declaration of Independence Abstract. This article assesses the evolution of the political landscape in Kosovo since its declaration of independence in 2008. It focuses on the first steps of institutional state- and democracy-building under the supervision of the international community. Secondly, it dis- cusses Serb-Albanian Relations, both in the context of Serbia’s contestation of Kosovo’s status and on the local level within Kosovo. With international assistance, considerable progress has been made in establishing a new governance framework, even though huge challenges still remain. Power struggles have led to a fragmentation of the Kosovar political landscape. Political conflicts, personal animosities and the socio-economic challenges facing the govern- ment constitute potential threats to Kosovo’s stability. At the same time, the security situation has somewhat improved. Hilde Katrine Haug is a Post-doctoral Fellow in the Department of Literature, Area Studies, and European Languages at the University of Oslo. From NATO’s intervention in 1999 until 17 February 2008, when Kosovo de- clared its independence, Kosovar Albanians and the political leadership in Prishtina were focused on making Kosovo an independent state. Kosovar Serbs, on the other hand, particularly those living north of the river Ibar, were equally focused on preventing Kosovo from becoming independent. These opposing goals continue to shape the political interests, expectations and fears of these two groups in Kosovo, often to the detriment of other issues affecting their everyday lives. Kosovar Albanians had long anticipated the declaration of independence and they had high expectations for this event. -

Interview with Zahrije Podrimqaku

INTERVIEW WITH ZAHRIJE PODRIMQAKU New Poklek, Drenas l Date: February 15, 2015 Duration: 302 minutes Present: 1. Zahrije Podrimqaku (Speaker) 2. Jeta Rexha (Interviewer) 3. Donjeta Berisha (Camera/Interviewer) 4. Kaltrina Krasniqi (Camera/Interviewer) Transcription notation symbols of non-verbal communication: () - emotional communication {} - the speaker explains something using gestures Other transcription conventions: [] - addition to the text to facilitate comprehension Footnotes are editorial additions to provide information on localities, names, or expressions Childhood [Cut from the video-interview: the interviewer asks the speaker about her childhood.] Zahrije Podrimqaku: I was born on February 10, 1970, in the village of Krajkova. I belong to a large, hardworking family and one that is well known for its hospitality and patriotism. My family in Drenica was a large family, made of around 30 family members. From the 21 children that he had (laughs), my grandfather, you know, had 16 alive. Of them, seven were boys and the rest were girls. As a child I, I started elementary school in my place of birth, my first teacher was Bedrie Hoxha, whom I take the opportunity to greet because she was a very good teacher, she taught us well and educated us well. Until fourth grade, I mean, I finished elementary school there, then with my family when, when we separated from the family we lived with, we left for Drenas around the year ‘82 and from fifth grade I started going to the school that today is called Rasim Keqina in Drenas, until eighth grade. During my education, I mean from first grade until fifth grade I was an excellent student, then by…with my engagements at home as well, because we were a large family and I was the oldest child, my parent worked abroad, meaning in Zagreb company at that time and I had to commit to my family from a young age. -

Kosovo Seems Headed for Period of Greater Political Stability, Secretary-General’S

5/13/2011 Kosovo Seems Headed for Period of Gre… 12 May 2011 Security Council SC/10250 Department of Public Information • News and Media Division • New York Security Council 6534 th Meeting (PM) KOSOVO SEEMS HEADED FOR PERIOD OF GREATER POLITICAL STABILITY, SECRETARY-GENERAL’S SPECIAL REPRESENTATIVE SAYS IN BRIEFING TO SECURITY COUNCIL Members Urge Investigation into Allegations of Trafficking in Human Organs Welcoming the recent start of a much-awaited dialogue between officials in Pristina and Belgrade, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General told the Security Council today that Kosovo had emerged from a constitutional crisis and appeared to be headed towards a period of increased political stability. Lamberto Zannier, who is also the Head of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), said the European Union-mediated dialogue — focused on technical and practical day-to-day matters such as civil registration, telecommunications, civil aviation, electricity and matters defined as “freedom of movement” issues — was crucial to resolving problems hampering development. “I am hopeful that both Pristina and Belgrade will demonstrate the resolve needed to find solutions to all relevant issues in a constructive spirit,” he said. Kosovo and Serbia must reconcile with each other, achieve regional integration and fully restore the administration of justice in northern Kosovo, where relations between the Kosovo Albanian and Kosovo Serb communities had been very tense and plans for the United Nations to conduct a census were being thwarted. Citing the lack of economic progress in Kosovo as a major obstacle to the return of refugees, he said efforts must continue to clarify the fates and locations of missing persons, investigate their disappearances and bring those responsible to justice.