Interview with Zahrije Podrimqaku

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Violence Against Kosovar Albanians, Nato's

VIOLENCE AGAINST KOSOVAR ALBANIANS, NATO’S INTERVENTION 1998-1999 MSF SPEAKS OUT MSF Speaks Out In the same collection, “MSF Speaking Out”: - “Salvadoran refugee camps in Honduras 1988” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - December 2013] - “Genocide of Rwandan Tutsis 1994” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “Rwandan refugee camps Zaire and Tanzania 1994-1995” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “The violence of the new Rwandan regime 1994-1995” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2003 - April 2004 - April 2014] - “Hunting and killings of Rwandan Refugee in Zaire-Congo 1996-1997” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [August 2004 - April 2014] - ‘’Famine and forced relocations in Ethiopia 1984-1986” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [January 2005 - November 2013] - “MSF and North Korea 1995-1998” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [January 2008 - 2014] - “War Crimes and Politics of Terror in Chechnya 1994-2004” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [June 2010 -2014] -”Somalia 1991-1993: Civil war, famine alert and UN ‘military-humanitarian’ intervention” Laurence Binet - Médecins Sans Frontières [October 2013] Editorial Committee: Laurence Binet, Françoise Bouchet-Saulnier, Marine Buissonnière, Katharine Derderian, Rebecca Golden, Michiel Hofman, Theo Kreuzen, Jacqui Tong - Director of Studies (project coordination-research-interviews-editing): Laurence Binet - Assistant: Berengere Cescau - Transcription of interviews: Laurence Binet, Christelle Cabioch, Bérengère Cescau, Jonathan Hull, Mary Sexton - Typing: Cristelle Cabioch - Translation into English: Aaron Bull, Leah Brummer, Nina Friedman, Imogen Forst, Malcom Leader, Caroline Lopez-Serraf, Roger Leverdier, Jan Todd, Karen Tucker - Proof reading: Rebecca Golden, Jacqui Tong - Design/lay out: - Video edit- ing: Sara Mac Leod - Video research: Céline Zigo - Website designer and webmaster: Sean Brokenshire. -

Judgement on Allegations of Contempt

IT-04-84-R77.4 p.1924 D1924-DI888 filed on: 17/12/08 UNITED He NATIONS Case No. IT-04-84-R77.4 International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 17 December 2008 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Alphons Orie, Presiding Judge Christine Van den Wyngaert Judge Bakone Justice Moloto Registrar: Mr. Hans Holthuis Judgement of: 17 December 2008 PROSECUTOR v. ASTRIT HARAQUA and BAjRUSH MORINA PUBLIC JUDGEMENT ON ALLEGATIONS OF CONTEMPT The Office ofthe Prosecutor: Mr. Daniel Saxon Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Karim A. A. Khan, Ms. Caroline Buisman and Ms. Gissou Azamia for Astrit Haraqija Mr. Jens Dieckmann for Bajrush Marina IT-04-84-R77.4 p.1923 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE ACCUSED 3 A. BAJRUSH MORINA 3 B. ASTRIT HARAQIJA 3 II. THE ALLEGATIONS 3 III. PROCEDURAL HISTORY 4 A. COMPOSITION OF THE TRIAL CHAMBER 4 B. DEFENCE COUNSEL 5 C. INITIAL ApPEARANCE 5 D. DETENTION AND PROVISIONAL RELEASE OF THE ACCUSED 5 E. EVIDENCE AND THE TRIAL 5 IV. APPLICABLE LAW 7 V. THE REQUIREMENT OF CORROBORATION 9 A. WHETHER THERE IS A NEED FOR CORROBORATION 9 B. THE REQUIREMENTS IN RELATION TO CORROBORATIVE EVIDENCE 10 VI. RESPONSIBILITY OF BAJRUSH MORINA 15 A. PREPARATIONS FOR THE JULY 2007 MEETINGS WITH WITNESS 2 15 B. MEETINGS OF JULY 2007 BETWEEN MORINA AND WITNESS 2 16 C. FACTS PRESENTED IN RELATION TO MOTIVE 17 D. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 18 VII. RESPONSIBILITY OF ASTRIT HARAQIJA 20 A. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

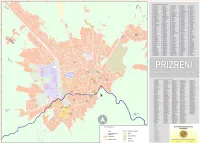

Map Data from the City of Prizren For

1 E E 3 <*- * <S V to v-v % X % 5.- ^s RADHITJA E EMRAVE SIPAS ALFABETIT -> 42 8 Marsi-7D 443 Brigáda 126-4C 347 Hysen Rexhepi-6E7E 253 Milan Šuflai-3H 218 Shaip Zurnaxhiu-4F 187 Abdy Beqiri-4E 441 Brigáda 128- 234 Hysen Trpeza-2E H 356 Mimar Sinan-6E 133 Shat Kulla-6E 1 Adem Jasharí-6E,5F 20 Bubulina-1A 451 Hysni Morína-3B 467 Mojsi Golemi-2A, 2B 424 Shefqet Berisha-80 | 360 Adnan Krasniqi-7E 97 Bujana-2D 46 Hysni Temaj- 25 Molla e Kuqe 390 Sheh Emini-7D 310 Adriatiku-5F 327 Bujar Godeni-6E 127 Ibrahim Lutfiu-6D 72 Mon Karavidaj-3C3D 341 Shn Albani-7F 38 Afrim Bytygi-1B,2B 358 Bujtinat-6E, 7E 259 Ibrahim ThagiSH 184 Morava-4E \J336 Shn Flori-6F, 7F 473 Afrim Krasniqi-9C 406 Burími-8D 45 Idriz Behluli- 23 Mreti Gllauk-1A \~345 Shn Jeronimi 1 444 Afrim Stajku-4C 261 Bushatlinjt-2H 39 llir Hoxha-1B 265 Muhamet Cami~3H 284 SherifAg TurtullaSG 446 Agim Bajrami-4C 140 Byrhan Shporta-6D 233 llirt-2E 21 Muhamet Kabashi-1A 29 Shestani | 278 Agim ShalaSF 47 Camilj Siharic 359 lljaz Kuka-6E,7E 251 Muharrem Bajraktarí-2H,3E 243 Shime Deshpali-2E 194 Agron Bytyqi-4E 56 Cesk Zadeja-3C 381 Indrit Cara -Kavaja-6D, 7D 74 Muharrem Hoxhaj-3C 291 Shkelzen DragajSF 314 Ahmet KorenicaSF 262 Dalmatt-3H 86 Isa Boletini-4D 458 Muharrem Samahoda-3B 199 Shkodra-3E \~286 293 Ahmet KrasniqiSF 475 Dardant-9C Islám Spahiu-5G l 316 MuhaxhirtSF \428 Shkronjat-7C, 7D 207 \Ahmet Prístina-5F4F 5 De Rada-6D, 5D \~7 Ismail Kryeziu-5D,4D 60 Mujo Ulqinaku-3C 138 Shote Galica-6D 447 Ajahidet-4C 61 Dd Gjon Luli-3C 40 Ismail Qemali-2B 1 69 Murat Kab ashi-4F, 5E 392 Shpend Berisha-7E -

PUBLIC Date Original: 26/10/2020 19:18:00 Date Corrected Version: 28/10/2020 14:39:00 Date Public Redacted Version: 05/11/2020 16:53:00

KSC-BC-2020-06/F00027/A08/COR/RED/1 of 5 PUBLIC Date original: 26/10/2020 19:18:00 Date corrected version: 28/10/2020 14:39:00 Date public redacted version: 05/11/2020 16:53:00 In: KSC-BC-2020-06 Before: Pre-Trial Judge Judge Nicolas Guillou Registrar: Dr Fidelma Donlon Date: 26 October 2020 Language: English Classification: Public Public Redacted Version of Corrected Version of Order for Transfer to Detention Facilities of the Specialist Chambers Specialist Prosecutor Defence for Jakup Krasniqi Jack Smith To be served on Jakup Krasniqi KSC-BC-2020-06/F00027/A08/COR/RED/2 of 5 PUBLIC Date original: 26/10/2020 19:18:00 Date corrected version: 28/10/2020 14:39:00 Date public redacted version: 05/11/2020 16:53:00 I, JUDGE NICOLAS GUILLOU, Pre-Trial Judge of the Kosovo Specialist Chambers, assigned by the President of the Specialist Chambers pursuant to Article 33(1)(a) of Law No. 05/L-53 on Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor’s Office (“Law”); BEING SEISED of the strictly confidential and ex parte “Submission of Indictment for Confirmation”, dated 24 April 2020, “Request for Arrest Warrants and Related Orders”, dated 28 May 2020, and “Submission of Revised Indictment for Confirmation”, dated 24 July 2020, of the Specialist Prosecutor’s Office (“SPO”); HAVING CONFIRMED, in the “Decision on the Confirmation of the Indictment Against Hashim Thaçi, Kadri Veseli, Rexhep Selimi and Jakup Krasniqi”, dated 26 October 2020, the Revised Indictment (“Confirmed Indictment”) and having found therein that there is a well-grounded suspicion that -

Downloaded 4.0 License

Security and Human Rights (2020) 1-5 Book Review ∵ Daan W. Everts (with a foreword by Jaap de Hoop Scheffer), Peacekeeping in Albania and Kosovo; Conflict response and international intervention in the Western Balkans, 1997 – 2002 (I.B.Tauris, July 2020), 228p. £. 13,99 paperback Fortunately, at the international scene there are those characters who venture into complex crises and relentlessly work for their solution. Sergio Viero de Melo seems to be their icon. Certainly, Daan Everts, the author of Peacekeeping in Albania and Kosovo belongs to this exceptional group of pragmatic crisis managers in the field. Between 1997 and 2002 he was the osce’s represent- ative in crisis-hit Albania and Kosovo. Now, twenty years later, Mr Everts has published his experiences, and luckily so; the book is rich in content and style, and should become obligatory reading for prospective diplomats and military officers; and it certainly is interesting material for veterans of all sorts. Everts presents the vicissitudes of his life in Tirana and Pristina against the background of adequate introductions to Albanian and Kosovar history, which offer no new insights or facts. All in all, the book is a sublime primary source of diplomatic practice. The largest, and clearly more interesting part of the book is devoted to the intervention in Kosovo. As a matter of fact, the 1999 war in Kosovo deepened ethnic tensions in the territory. Therefore, the author says, the mission in Kosovo was highly complex, also because the mandate was ambivalent with regard to Kosovo’s final status. Furthermore, the international community (Everts clearly does not like that term) for the time being had to govern Kosovo as a protectorate. -

Report Between the President and Constitutional Court and Its Influence on the Functioning of the Constitutional System in Kosovo Msc

Report between the President and Constitutional Court and its influence on the functioning of the Constitutional System in Kosovo MSc. Florent Muçaj, PhD Candidate Faculty of Law, University of Prishtina, Kosovo MSc. Luz Balaj, PhD Candidate Faculty of Law, University of Prishtina, Kosovo Abstract This paper aims at clarifying the report between the President and the Constitutional Court. If we take as a starting point the constitutional mandate of these two institutions it follows that their final mission is the same, i.e., the protection and safeguarding of the constitutional system. This paper, thus, will clarify the key points in which this report is expressed. Further, this paper examines the theoretical aspects of the report between the President and the Constitutional Court, starting from the debate over this issue between Karl Schmitt and Hans Kelsen. An important part of the paper will examine the Constitution of Kosovo, i.e., the contents of the constitutional norm and its application. The analysis focuses on the role such report between the two institutions has on the functioning of the constitutional system. In analyzing the case of Kosovo, this paper examines Constitutional Court cases in which the report between the President and the Constitutional Court has been an issue of review. Such cases assist us in clarifying the main theme of this paper. Therefore, the reader will be able to understand the key elements of the report between the President as a representative of the unity of the people on the one hand and the Constitutional Court as a guarantor of constitutionality on the other hand. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The term ‘humanitarian war’ was first coined by Adam Roberts. See his, ‘Humanitarian War: Intervention and Human Rights’, International Affairs, 69(2), 1993 and, ‘NATO’s Humanitarian War Over Kosovo’, Survival, 41(3), 1999. 2. The issue of intra-alliance politics is discussed throughout Pierre Martin and Mark R. Brawley (eds), Alliance Politics, Kosovo, and NATO’s War: Allied Force or Forced Allies? (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000). 3. Formally recognised by the EU and UN as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) but referred to as Macedonia throughout. 4. The idea of the ‘court of world opinion’ was put to me by Nicholas Wheeler. See Nicholas J. Wheeler, Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). 5. Trotsky is cited by Noel Malcolm, Kosovo: A Short History (London: Papermac, 1999), p. 253. 6. Ibid. 7. Ibid., pp. 324–6. For a general overview of the key aspects of the conflict see Arshi Pipa and Sami Repishti, Studies on Kosova (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), Robert Elsie (ed.), Kosovo: In the Heart of the Powder Keg (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997). 8. See Lenard J. Cohen, Broken Bonds: Yugoslavia’s Disintegration and Balkan Politics in Transition, 2nd edn (Oxford: Westview, 1995), p. 33. 9. Article 4 of the Constitution of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, 1974. See Marc Weller, The Crisis in Kosovo 1989–1999: From the Dissolution of Yugoslavia to Rambouillet and the Outbreak of Hostilities (Cambridge: International Documents and Analysis, 1999), p. 58. 10. Article 6 of the Kosovo Constitution, 1974. -

Albania Pocket Guide

museums albania pocket guide your’s to discover Albania theme guides Museums WELCOME TO ALBANIA 4 National Historic Museum was inaugurated on 28 October 1981. It is the biggest Albanian museum institution. There are 4750 objects inside the museum. Striking is the Antiquity Pavilion starting from the Paleolithic Period to the Late Antiquity, in the 4th century A.D., with almost 400 first class objects. The Middle Age Pavilion, with almost 300 objects, documents clearly the historical trans- formation process of the ancient Illyrians into early Arbers. CONTENTS i 5 TIRANA 6 DURRES 14 ELBASAN 18 LUSHNJE 20 KRUJE 20 APOLLONIA 26 VLORA 30 KORÇA 34 GJIROKASTRA 40 BERATI 42 BUTRINTI 46 LEZHE 50 SHKODER 52 DIBER 60 NATIONAL HISTORIC MUSEUMS TIRANA 6 National Historic Museum was inaugurated on 28 October 1981. It is the biggest Albanian museum institution. Pavilion starting from the Paleolithic Period to the Late Antiquity, in the 4th century A.D., with almost 400 first class objects. The Middle Age Pavilion, with almost 300 objects, documents clearly the historical transformation process of the ancient Illyrians into early Arbers. This pavilion reflects the Albanian history until the 15th century. Other pavilions are those of National Renaissance, Independence and Albanian State Foundation, until 1924. The Genocide Pavilion with 136 objects was founded in 1996. The Iconography Pavilion with 65 first class icons was established in 1999. The best works of 18th and 19th century painters are found here, like Onufër Qiprioti, Joan Çetiri, Kostandin Jermonaku, Joan Athanasi, Kostandin Shpataraku, Mihal Anagnosti and some un- known authors. In 2004 the Antifascism Pavilion 220 objects was reestablished. -

Doing Business in South East Europe 2011 and Other Subnational and Regional Doing Business Studies Can Be Downloaded at No Charge At

COMPARING BUSINESS REGULATION ACROSS THE REGION AND WITH 183 ECONOMIES A COPUBLICATION OF THE WORLD BANK AND THE INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www.worldbank.org E-mail [email protected] All rights reserved. A publication of the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation. This volume is a product of the staff of the World nkBa Group. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone 978-750-8400; fax 978- 750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2422; e-mail: pubrights@worldbank. org. Doing Business in South East Europe 2011 and other subnational and regional Doing Business studies can be downloaded at no charge at www.doingbusiness.org/subnational. -

Buzuku 33 11

numër 33 Revistë informative, kulturore e shoqërore Ulqin, e enjte më 2 shtator 2010, çmimi 1€, 2$ Përkujtojmë 100 vjetorin e lindjes së Nënës Tereze 2 Lexuesit na shkruajnë 33/2010 Shestanasi bjesedon me nipin Pjetri Markut Pjetrit Si m'ke n'jeh, sokoli i gjyshit? A ke fjetë? Në numrin e kaluar të revistës tonë patëm rastin ta njohim një djalë Mos dvet! Kam pa n'gjumë babën tan, Kocin, shestanas, Sandrin e Preçit, frizer me renome ndërkombëtare. Këtu po krejt ashtu si m'ke bjeseduo ti: Burrë i madh, i japim një figurë tjetër të kësaj treve. vishun me pekta leshit, i njishun me brez Pjetri Markut Pjetrit Markut Pjetër Gjurs, prej Bardhonjsh të Salçit, tash tarabullus, mustakë vesh n'vesh… si hypi në Braticë, Ulqin, 18 vjeçar, na flet për revistën tonë. Qe në moshën 12 n'shpí, ka metë harú! vjeçare i hyri sportit atraktiv të karatesë si një aventurë për këtë moshët. A je ti stërnipi jem, m'dveti? Edhe ma aviti Por shumë shpejt u kuptua se ky sport nuk ishte vetëm një aventurë por dorën te buza. Unë e shikova i habitun! A s't'kanë suo se duhet plakut me'j puthë dorën, ishte një thirrje dhe një dhuratë. Shumë shpejt edhe trejnerët dhe familja e jo!? Eeee, eh, s'ke faj ti, por djali i jem e jytat. kuptuan se karateja nuk ishte një kalim kohe për të, por një sport qe e kishte Po, i kanë hupë të tana çka u kam lanë unë. pasion. Tregon Pjetri se në moshën 14 vjeçare korri suksesin e parë në një turnir në Maqedoni ku zuri vendin e tretë, dhe mandej pasuan sukseset një mbas një; më 2007 u bë kampion i Malit të Zi. -

Gjoka Konstruksion

143 www.rrugaearberit.com GAZETË E PAVARUR. NR. 3 / 2018. ÇMIMI: 50 LEKË. 20 DENARË. 1.5 EURO. Intervistë Art Profil Dr. Ahmet Alliu, Bajram Mata zgjodhi Pajtim Beça, një mjeku i parë i Dibrës të jetojë me fjalën e histori suksesi në Historiku i shërbimit shëndetësor në veprat e realizuara breg të Drinit optikën e mjekut të parë dibran Nga prof.as.dr.Nazmi KOÇI 16 Nga Selami NAZIFI 12 Nga Osman XHILI 9 NË BRENDËSI: Rruga e Arbrit: Qeveria firmos kontratën, Jemi skeptike për aq kohë sa nuk ka transparencë për fondet dhe projektin “Gjoka Konstruksion” gati të nisë punën Rruga e Arbrit i bashkon shqiptarët Dhjetë arsye përse duhet vizituar Dibra Rafting lumenjve të Dibrës që s’bëzajnë “FERRA E PASHËS” Jashar Bunguri, gjeneral i bujqësisë shqiptare Kastrioti, fshati pa Kastriotë Asllan Keta: Më shumë se Partinë, dua Shqipërinë Tenori Gerald Murrja: Ëndrra ime është të këndoj në skenat e operave në botë Shkolla Pedagogjike e Peshkopisë, tempull i dijes dhe edukimit Mustafa Shehu, një zemër Lexoni në faqen 2 që skaliti me zjarr emrin e tij në histori REPORTAZH SPORT: Alia dhe Halili, dy dibranët e Kombëtares U-19 Fadil Shulku, portieri modern i kohës Cerjani, një fshat Drini Halili:Objektivi është Kombëtarja!. Shqiponja dibrane i braktisur dhe i Marko Alia: Mes Italisë dhe Shqipërisë zgjodha vendin tim! Njerëz që hynë dhe mbetën në kujtesën e dibranëve rrënuar nga migrimi Islamil Hida, njeri i edukuar, fjalëpak e punëshumë Më shumë mund të shikoni në faqen e gazetës Nga BESNIK LAMI në FB: Rruga e Arbërit ose ndiq linkun: https://tinyurl.com/lcc3e2f erjani është një nga katër fshatrat e zonës së CBellovës që shtrihet në verilindje të qytetit të Peshkopisë, rreth 7 km larg tij.