Learning Design in a Global Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gospel and Globalization

the Gospel and Globalization Exploring the Religious Roots of a Globalized World Edited by Michael W. Goheen Erin G. Glanville Regent College Press • Geneva Society Vancouver, B.C., Canada THE GOSPEL AND GLOBALIZATION: EXPLORING THE RELIGIOUS ROOTS OF A GLOBALIZED WORLD Copyright © 2009 Regent College Publishing All rights reserved. Published 2009 by REGENT COLLEGE PUBLISHING 5800 University Boulevard / Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 2E4 / Canada / www.regentpublishing.com with GENEVA SOCIETY www.genevasociety.org Cover image by Ben Goheen Typeset by Dan Postma No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or the Copyright Licensing Agency. Views expressed in works published by Regent College Publishing are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of Regent College (www.regent-college.edu). Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication The Gospel and globalization : exploring the religious roots of a globalized world / edited by Michael W. Goheen and Erin G. Glanville. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-57383-440-7 1. Globalization—Religious aspects—Christianity. 2. Globalization— Religious aspects—Islam. 3. Capitalism—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Capitalism—Religious aspects—Islam. 5. Globalization—Moral and ethical aspects. 6. Globalization—Economic aspects. 7. Christian ethics. 8. World politics. I. Goheen, Michael W., 1955- II. Glanville, Erin G., 1980- BL65.G55G68 2009 201’.7 C2009-902767-4 For Phoebe Shalom, because the future is secure Table of Contents Preface 7 Introduction 11 Michael W. Goheen and Erin G. -

BC's Faith-Based Postsecondary Institutions

Made In B.C. – Volume II A History of Postsecondary Education in British Columbia B.C.’s Faith-Based Postsecondary Institutions Bob Cowin Douglas College April 2009 The little paper that keeps growing I had a great deal of fun in 2007 using some of my professional development time to assemble a short history of public postsecondary education in British Columbia. My colleagues’ interest in the topic was greater than I had anticipated, encouraging me to write a more comprehensive report than I had planned. Interest was such that I found myself leading a small session in the autumn of 2008 for the BC Council of Post Secondary Library Directors, a group that I enjoyed meeting. A few days after the session, the director from Trinity Western University, Ted Goshulak, sent me a couple of books about TWU. I was pleased to receive them because I already suspected that another faith-based institution, Regent College in Vancouver, was perhaps BC’s most remarkable postsecondary success. Would Trinity Western’s story be equally fascinating? The short answer was yes. Now I was hooked. I wanted to know the stories of the other faith-based institutions, how they developed and where they fit in the province’s current postsecondary landscape. In the ensuing months, I poked around as time permitted on websites, searched library databases and catalogues, spoke with people, and circulated drafts for review. A surprisingly rich set of historical information was available. I have drawn heavily on this documentation, summarizing it to focus on organizations rather than on people in leadership roles. -

2021 Catalog 2 3

2020- 2021 1 Hillsdale College 2020 - 2021 Catalog 2 3 Welcome to Hillsdale College independent, four-year college in south-central Michigan, Hillsdale College offers the An rigorous and lively academic experience one expects of a tier-one liberal arts college, and it stands out for its commitment to the enduring principles of the Western tradition. Its core curriculum embodies this commitment through required courses in disciplines such as history, literature, science and politics in order to develop in students the “philosophical habit of mind” essential to sound education. Likewise, majors at Hillsdale are a rigorous and searching extension of these commitments. Ranging from classics or music to chemistry or business, academic fields of concentration build upon the core curriculum, deepening and specifying students’ appreciation for and understanding of the liberal arts. Hillsdale College is dedicated to intellectual inquiry and to learning, and it recognizes essential human dignity. Ordered liberty, personal responsibility, limited government, free enterprise and man’s moral, intellectual and spiritual nature illuminate this dignity and identify the service of the College to its students, the nation, and the Western intellectual and religious tradition. Far-ranging by design and incisive by method, study at Hillsdale College is intellectually demanding. Students work closely with faculty who guide them in their studies, helping students to prepare for a lifetime of accomplishment, leadership, and learning. For more information about Hillsdale College or to arrange a visit, call the Admissions Office at (517) 607-2327, or e-mail [email protected]. • College, founded in 1844, is an independent, coeducational, resi- Hillsdale dential, nonsectarian college for about 1,460 students. -

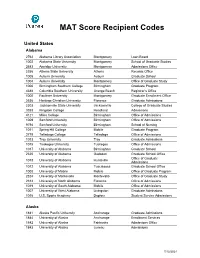

MAT Score Recipient Codes

MAT Score Recipient Codes United States Alabama 2762 Alabama Library Association Montgomery Loan Board 1002 Alabama State University Montgomery School of Graduate Studies 2683 Amridge University Montgomery Admissions Office 2356 Athens State University Athens Records Office 1005 Auburn University Auburn Graduate School 1004 Auburn University Montgomery Office of Graduate Study 1006 Birmingham Southern College Birmingham Graduate Program 4388 Columbia Southern University Orange Beach Registrar’s Office 1000 Faulkner University Montgomery Graduate Enrollment Office 2636 Heritage Christian University Florence Graduate Admissions 2303 Jacksonville State University Jacksonville College of Graduate Studies 3353 Kingdom College Headland Admissions 4121 Miles College Birmingham Office of Admissions 1009 Samford University Birmingham Office of Admissions 9794 Samford University Birmingham School of Nursing 1011 Spring Hill College Mobile Graduate Program 2718 Talladega College Talladega Office of Admissions 1013 Troy University Troy Graduate Admissions 1015 Tuskegee University Tuskegee Office of Admissions 1017 University of Alabama Birmingham Graduate School 2320 University of Alabama Gadsden Graduate School Office Office of Graduate 1018 University of Alabama Huntsville Admissions 1012 University of Alabama Tuscaloosa Graduate School Office 1008 University of Mobile Mobile Office of Graduate Program 2324 University of Montevallo Montevallo Office of Graduate Study 2312 University of North Alabama Florence Office of Admissions 1019 University -

Fall Issue 08

FRIENDSHIP ISSUE 10 November 2020 // Fall Issue 8 “Friendship is unnecessary, like philosophy, like art...It has no survival value; rather it is one of those things which give value to survival.” C.S. Lewis In Memoriam of the Community House Brother Moving Out By Derek Hiemstra “What’s up, short stuff?” I’d ask as he walked in the door. “What’s up, tall stuff?” he’d reply. It was stupid. Sometimes we’d change it up: “What’s up, big guy?” I’d say. “What’s up, small guy?” he’d reply. I’m still looking for the death and resurrection, or the incarnation, or the trinity, agape,orthekingdom of God in my front hallway. I know that’s unrelated but I’ve got my eyes open. Adrian is a brick-layer, and he looks like it. Sturdy, stolid. Dark brown hair in a mohawk, dark full beard. Often, he’d wear a light blue shirt with a white, handwritten script on it. The shirt read, “Y’all need Jesus” on the front, and he claims that some friends of his bought it for him as a joke. Maybe we don’t need one, but I like to think everyone should enjoy an Adrian now and then. Just for the solidity of it. Adrian and I went for a run one afternoon in Pacifc Spirit Park. And that’s just one fun thing he does. He also covered my rent once (I paid him back in full, thank you) and he thought out loud in front of me that if I sold my body on Craigslist it could help me make rent next time. -

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS 2000/01 Ministry Abbreviations

PublicAccounts 2000/01 SupplementaryInformation DetailedSchedulesofPayments PublicAccounts 2000/01 SupplementaryInformation DetailedSchedulesofPayments FortheFiscalYearEnded March31,2001 Detailed Schedules of Payments for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2001 (Unaudited) Contents Page Ministry Abbreviations.................................................................................................................................... 5 Summary of Payments .................................................................................................................................... 6 Members of the Legislative Assembly Compensation ....................................................................................... 7 Schedules of Salary and Travel Expenses for: Ministers ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Deputy Ministers and Associate Deputy Ministers................................................................................... 10 Order–In–Council, Other Appointees and Employees not Appointed under the Public Service Act........... 11 Other Employees................................................................................................................................... 19 Grants and Contributions................................................................................................................................ 26 Other Suppliers ............................................................................................................................................. -

AXEL UWE SCHOEBER Curriculum Vitae Life

AXEL UWE SCHOEBER Curriculum Vitae Life events Born in Ponoka, Alberta on June 18, 1955. Canadian citizen. Raised in Vancouver, British Columbia. Married Karen in March, 1977. Two children: a girl (Kayely), born in 1982, ordained with Canadian Baptists of Western Canada, but now a retail manager in Regina, Saskatchewan; a boy (Trevor), born in 1987, B.A.in economics at the University of Victoria and a banker. Coached 4 Penticton Boys Youth Soccer Teams to Interior Championships (2000-03) Professional Work Elementary Teacher (Grade 5) in Lillooet, British Columbia, 1976-78 Pastor, Jasper Park Baptist Church, Jasper, Alberta, 1982-85 Chaplain, Seton General Hospital, Jasper, Alberta, 1983-85 (part-time) Pastor, Bowness Baptist Church, Calgary, Alberta, 1986-92 Pastor, First Baptist Church, Penticton, British Columbia, 1992-2003 Adjunct Professor in History and Theology, Carey Theological College, Vancouver, British Columbia, 2000-2008 Pastor, First Baptist Church, Victoria, British Columbia, 2003-2008 Associate Professor of Supervised Ministry, Carey Theological College, Vancouver, British Columbia, 2009-present Schooling Prince of Wales Secondary School, Vancouver, British Columbia. Graduated 1972. History Book Prize. Bachelor of Elementary Education, University of British Columbia, 1976. Concentration in History and Elementary Social Studies Pedagogy. Diploma in Christian Studies, Regent College, Vancouver, British Columbia, 1979. Book Prize for Highest Grade Point Average. Master of Divinity, Regent College, 1981. Book Prizes for Hebrew and for Highest Grade Point Average. Master of Theology, Regent College, 1987. 300 page historical thesis on the nature of Paul’s adversaries referred to in the book of Colossians (based on the Greek text). Doctor of Ministry, Faith Lutheran Seminary, Tacoma, Washington. -

University College Personnel.Pdf

UNIVERSITY PERSONNEL PRESIDENT Michael DeMoor, Associate Professor of Social Philosophy in Politics, History and Economics Melanie J. Humphreys Director of Politics, History, Economics B.A. (1994); M.A. (2001) Trinity Western University; B.A. (Honors) (2000), The King's University College; M. Ph.D. (2007) Azusa Pacific University Phil. (2003), Institute for Christian Studies; Ph.D. (2011), Institute for Christian Studies/Vrije Universiteit VICE PRESIDENT ACADEMIC AND Lloyd Den Boer, Associate Professor of Education RESEARCH Dean of Faculty of Education Hank D. Bestman B.A. (1973) Dordt College; M.A. (1984) Simon Fraser B.A. (1979), Dordt College; M.Sc. (1982); Ph.D. (1988), University; Ed.D. (in progress), University of South University of Alberta Dakota VICE PRESIDENT Neal DeRoo, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Canada Research Chair in Phenomenology and Philosophy of ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE Religion Ellen Vlieg-Paquette B.A. (2003) Calvin College; M.A. (2005) Institute for B.A. (1976), Dordt College; C.A. (1981), Institute of Christian Studies; Ph.D. (2009) Boston College Chartered Accountants of Alberta; Microcomputer Jeffrey Dudiak, Professor of Philosophy Accounting Certificate (with Distinction) (1997), Grant B.A. (1983), Malone College; M.A. (1987), Duquesne MacEwan Community College University; M.Phil.F. (1987), Institute for Christian Studies; Ph.D. (1998), Free University in Amsterdam VICE PRESIDENT ADVANCEMENT Amy Feaver, Assistant Professor of Computing Science and Dan VanKeeken Mathematics BPA (with Great Distinction) (2009), Athabasca B.S. (2007), Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute; M.A. (2010), University; Certificate in Corporate Community Relations Ph.D. (2014), University of Colorado (1996), Boston College; Accredited in Public Relations, Michael Ferber, Vice President Student Development Canadian Public Relations Society (2016); Certified Fund B.A. -

February 2020

Published by the University Neighbourhoods Association Volume 11, Issue 2 FEBRUARY 24, 2020 Letter to the UBC Community from UBC President Robert H. Lee, CM, OBC 1933-2020 It is with deep sadness and a great sense of Bob was extremely devoted to the service loss that we learned of the passing of Dr. of his alma mater, serving two terms on the Robert (Bob) H. Lee, CM, OBC, former UBC Board of Governors. He was installed Chancellor of UBC and Chairman of UBC as chancellor in 1993, served as chair of the Please see story by Michael Li Hearts for Hubei: Lending our Heroes a Hand on Page 8. Properties Trust on February 19, 2020. I UBC Foundation, and was the honorary would like to express my heartfelt condo- chair of UBC’s start an evolution campaign. lences to Bob’s family on behalf of the entire UBC awarded Bob an Honorary Doctorate UBC community; he will be deeply missed. of Laws in 1996, and in 2006 the Robert H. Board Permits UNA Director Lee Graduate School at the Sauder School Esteemed philanthropist, visionary and be- of Business was established in recognition in Self-Isolation to Participate loved community leader Bob Lee was one of Bob’s generous gift to support graduate of UBC’s most accomplished alumni. Bob business education. In appreciation of Bob’s dedicated much of his life, expertise and personal and other contributions to UBC in Meeting from Home resources to building a brighter future for totaling over $15 million, members of the British Columbians and Canadians, and he community came together to name the Rob- Director was under self- cided to remain isolated for a period ending embodied the mission of UBC and its vision ert H. -

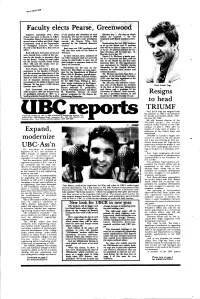

Expand, UBC-Ass'n Resigns TRIUMF

Prof. Erich Vogt Resigns to head TRIUMF Prof. Erich Vogt has resigned from his position asUBC’s vice-president for faculty and student affairs, effec- tive June 30, 1981. He will become director of the TRIUMFproject, thenuclear research facility located on the UBC campus, onJuly 1, 1981, after six months of studyleave at similar in- Expand, stallations in the United States and I Switzerland. TRIUMF is Canada’s largest new modernize venture in science in the last decade and is just now entering its most pro- ductive initial years. Dr. Vogt said the opportunity to head theproject is “one UBC-Ass’n of the mostchallenging and interes- The Asscciation of Professional ting to be given to a Canadian scien- Engineers of B.C. says facilities in tist _*’ UBC’s Faculty of AppliedScience Prof. Vogt’sresignation will result shouldbe“modernized and in a rearrangement of administrative expanded” to train more engineers. responsibilities in the President’s Of- And the association, which licenses fice at UBC. engineers to practise in B.C., says it is Vice-president Vogt’s duties as vice- notconvinced thatthe most cost- president for faculty affairs will be effective or desirable approach to in- transferred to theoffice of Prof. creasing the supply of engineers would MichaelShaw, whose title of vice- be the creation of a new engineering presidentfor academic development school at this time. hasbeen changed to vice-president, The association’s recommendations academic, and provost. for upgradingand expanding UBC Prof. Shaw will share responsibility facilities, aswell as for a stepped-up for faculty affairs with Prof. -

ETC-Winter-Issue-02.Pdf

FIRST YEARS ISSUE 19 January 2021 // Winter Issue 2 Happy Surprises and Reflections on Psalm 8 By Beth Cormack LORD, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth! (Psalm 8:1) I had intended to spend Christmas and New Year with a cousin in Alberta but changed plans in accordance with the health advisories. As I strolled along the Vancouver seafront on a damp New Years’ Eve, I pondered on how different the celebrations for the end of 2020 were in comparison to the year before. On December 31st 2019, friends and I had stood on a balcony in London, champagne in hand, enjoying the fireworks above the River Thames. We toasted in the year, joined hands and sang Auld Lang Syne, before retreating back into the warmth of the apartment. From the laughter of ‘old’ friends to the many ‘happy surprises’ of wonderful people on the West Coast of Canada, I am so thankful for 2020. So thankful to be here, at Regent College, to contemplate God’s majesty as I study his Word alongside others, and see it reflected in the beauty and grandeur of the Vancouver Mountains and ocean. When I consider the heavens…what is mankind that you are mindful of them, human beings that you care for them? (Psalm 8:3-4) It seems miraculous to be here at all. Having been granted leave from my post as kindergarten teacher in London, I wondered whether I would have to complete my Regent studies back in the UK. But I longed for a change of scene! In the meantime, a family friend contacted me to offer the use of their basement suite, where I could quarantine and then stay on. -

6Th Congress of the International Society for Theoretical Chemical Physics Book of Abstracts and Program

6th Congress of the International Society for Theoretical Chemical Physics Book of Abstracts and Program July 19−24, 2008 University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Chair: Yan Alexander Wang (Canada) Co-chairs: Erkki Brändas (President of ISTCP, Sweden) Jean Maruani (France) Table of Contents Welcome Message i List of Sponsors ii Committee iii Program 1 Timetable 2 Congress Lectures 3 Symposium Schedule 4 SMS 4 SMD 6 CCT 8 ERD 9 SIN 12 FCS 14 SSS 16 CCU 17 ATS 19 BMS 21 CMS 23 DFT 24 OFD 26 SQT 27 QMC 29 Poster Schedule 31 Poster Session I 31 Poster Session II 32 Poster Session III 33 Abstracts 34 List of Participants 209 Additional Information 222 CRC Press Award for Excellence in Chemical Physics Taylor & Francis Group/CRC Press has generously sponsored a book award, the CRC Press Award for Excellence in Chemical Physics, for poster presentations given by postdoctoral fellows and students at ISTCP-VI. Each awardee will receive one copy of the latest 88th edition of the “CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics.” During the Congress Banquet on July 23, three recipients of this book award will be announced. i Welcome It is our great pleasure to welcome you to the Sixth Congress of the International Society for Theoretical Chemical Physics (ISTCP-VI) at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. The International Society for Theoretical Chemical Physics (ISTCP) was founded in 1991 by Professor János Ladik, at the University of Erlangen, Germany, together with other prominent scientists. Its aim is to promote all theoretical developments on problems at the frontier between physics and chemistry.