The Despenser Forfeitures 1400-61

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masaryk University Faculty of Education

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature We, Band of Brothers in Arms Friendship and Violence in Henry V by William Shakespeare Bachelor thesis Brno 2016 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Jaroslav Izavčuk Vladimír Ovčáček Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma ‘We, Band of Brothers in Arms - Friendship and Violence in Henry V by William Shakespeare’ vypracoval samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů. Souhlasím, aby práce byla uložena na Masarykově univerzitě v Brně v knihovně Pedagogické fakulty a zpřístupněna ke studijním účelům. V Brně dne………………………….. Podpis………………………………. - 1 - I would like to express my gratitude to my parents and friends, without whose support I would never have a chance to reach this important point of my life. I would also like to thank Mgr. Jaroslav Izavčuk for his kind support, helpful advice, and patience. - 2 - Anotace Tato bakalářská práce analyzuje hru Jindřich V. od Wiliama Shakespeara, a to z hlediska násilí a přátelství, jakožto témat často se objevujících v této hře. Bakalářská práce je tvořena teoretickou a praktickou částí. V teoretické části je popsán děj hry a jsou zde také určeny cíle této práce. Dále jsou zde charakterizovány termíny násilí a přátelství a popsán způsob jakým bylo v renesančním dramatu vnímáno násilí. Dále jsem zde vytvořil hypotézu a definoval metody výzkumu. Na konci teoretické části je stručný popis historického kontextu, do kterého je tato hra včleněna. -

1 1 F. Taylor and J. S. Roskell (Eds.),Gesta Henrici Quinti (Oxford

1 Representation in the Gesta Henrici Quinti Kirsty Fox ‘Not in the strict sense a chronicle or history, and certainly not a ‘compilation’, it is rather an original and skilful piece of propaganda in which narrative is deliberately used to further the larger theme.’ Categorisation of the anonymous Gesta Henrici Quinti, which describes the events of the reign of Henry V from his accession in 1413 to 1416, proves problematic for historians.1 Written during the winter of 1416 and the spring of 1417, it is thought that the author may have been an Englishman in priest’s orders, belonging to the royal household. A great deal of work has been focused on identifying the context and purpose of the Gesta, in the hope that this may reveal the identity of the author and the occasion for which it was written.2 But little attention has been paid to how it was written; although Roskell and Taylor have stated that the narrative was used to ‘further the larger theme’, no detailed analysis of this narrative has been undertaken. The author’s clerical background clearly had some bearing on the religious framework of the text, and attention will be paid to this issue. This essay aims to pursue a more literary analysis of the Gesta, examining the subject of character through a discussion of treason and heresy, and that of causation through discussion of Biblical imagery and prophecy. It has been suggested that the text was intended to be used by English negotiators at the Council of Constance.3 A detailed reading of the narrative may substantiate this, or point to other directions for the Gesta’s intended audience, for example, international opinion, a domestic audience, the Church, or 1 F. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire. -

Allegation: It Is Alleged That Richard III Was an Unpopular King, His

Allegation: It is alleged that Richard III was an unpopular king, his unpopularity arising thanks to the evil character he revealed in his usurpation of the throne of England. And further, that this unpopularity led to the occurrence of rebellions during his reign, the earliest only 3 months after his coronation. It was also the cause of his failure to control the south of England, and of his ultimate failure at Bosworth when his subjects refused to fight for him. Rebuttal Synopsis: In his lifetime Richard was seen by many as having exactly the qualities desired in a medieval monarch. Richard’s assumption of the throne was approved by parliament; Mancini’s report to Angelo Cato in December 1483, was written in Latin and used the word “occupatione”which has been inaccurately translated as “usurpation.” Richard’s reign was not unique in the occurrence of rebellions and plots against his authority; other medieval monarchs required much longer than 26 months to stabilize their reigns. There was only one rebellion (in October 1483, easily quashed). It represented a coalescence of several interest groups, each with its own agenda, but sharing a common need to remove Richard before their own interests could advance. Richard's actions in creating "plantations" of his northern followers in southern counties were a necessary reaction to fill the voids created in the fabric of local government after the removal and/or flight of numbers of southerners who had been involved in the October rebellion.. The outcome of Bosworth was decided by the betrayal of two or three men with sizeable armies at their command who came to the field ostensibly to fight for their king, Richard. -

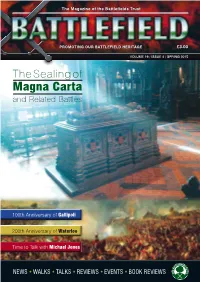

Battlefields 2015 Spring Issue

The Magazine of the Battlefields Trust PROMOTING OUR BATTLEFIELD HERITAGE £3.00 VOLUME 19 / ISSUE 4 / SPRING 2015 The Sealing of Magna Carta and Related Battles 100th Anniversary of Gallipoli 200th Anniversary of Waterloo Time to Talk with Michael Jones NEWS • WALKS • TALKS • REVIEWS • EVENTS • BOOK REVIEWS The Agincourt Archer On 25 October 1415 Henry V with a small English army of 6,000 men, made up mainly of archers, found himself trapped by a French army of 24,000. Although outnumbered 4 to 1 in the battle that followed the French were completely routed. It was one of the most remarkable victories in British history. The Battlefields Trust is commemorating the 600th anniversary of this famous battle by proudly offering a limited edition of numbered prints of well-known actor, longbow expert and Battlefields Trust President and Patron, Robert Hardy, portrayed as an English archer at the Battle of Agincourt. The prints are A4 sized and are being sold for £20.00, including Post & Packing. This is a unique opportunity; the prints are a strictly limited edition, so to avoid disappointment contact Howard Simmons either on email howard@ bhprassociates.co.uk or ring 07734 506214 (please leave a message if necessary) as soon as possible for further details. All proceeds go to support the Battlefields Trust. Battlefields Trust Protecting, interpreting and presenting battlefields as historical and educational The resources Agincourt Archer Spring 2015 Editorial Editors’ Letter Harvey Watson Welcome to the spring 2015 issue of Battlefield. At exactly 11.20 a.m. on Sunday 18 June 07818 853 385 1815 the artillery batteries of Napoleon’s army opened fire on the Duke Wellington’s combined army of British, Dutch and German troops who held a defensive position close Chris May to the village of Waterloo. -

Hampshire: a County’S Role in the Agincourt Campaign of All the Battles Throughout the Hundred Years War, the Battle of Agincourt Is by Far the Most Well-Known

Hampshire: A County’s Role in the Agincourt Campaign Of all the battles throughout the Hundred Years War, the Battle of Agincourt is by far the most well-known. The famous story of a small, bedraggled English army of 12,000 paid soldiers led by the gallant King Henry V defeating the well-equipped French force numbering over 30,000 in the summer of 1415 has gone down in English legend, perhaps being the greatest underdog tale in English military history. As a result, many novels, academic books and plays pay testament to the victory; most notably William Shakespeare’s Henry V. Although the fighting took place on French soil, many significant events of the campaign - and much of the planning - took place in the county of Hampshire, located on the south coast of England. From treacherous plots to overthrow the king, to local knights who valiantly fought against their powerful foe, Hampshire played a pivotal role in the victory. In order to send troops over to France, Henry V needed to muster his men in one place – being situated on the south coast, Southampton was one of the cities chosen to muster retinues for the expedition. This city, with its high stone walls and large natural harbour, was deemed to be the perfect starting point for the campaign, and became the assembly point for men from all over England and Wales who marched to honour their king’s call to arms. In the weeks leading up to their departure, over 5,000 soldiers descended on the city and surrounding area, sleeping in billets outside the city walls. -

Commemorating Agincourt As Part of the Primary History Curriculum

Commemorating Agincourt as part of the primary history curriculum Mel Jones and Kerry Somers In August 2015, the Historical Association was awarded a grant to carry out four education projects to commemorate the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt. The four projects were designed to appeal to different age groups across the curriculum. Two of the projects appealed to children in Key Stage 2. The first of these was an exhibition competition and the second was a bilingual history and French project which saw children visiting the Agincourt battlefield itself in northern France. The Do They Learn About Agincourt in France? project saw children in Years 5, 6 and 7 Pupils from Wellow School in Romsey prepare taking part in a bilingual enquiry for their visit to Agincourt by meeting a local archer. examining interpretations of Picture courtesy of the Southern Daily Echo, Southampton the Battle of Agincourt. The HA The following account charts the production of these and we look commissioned the Association for experience of the project from forward to seeing the results. Language Learning to be a part of the perspective of one successful the development of the enquiry applicant, Wellow School, from the This is the teacher view but how did which is published for open access initial historical enquiry to the visit the children feel? The short answer on the HA website: itself. Now that they have returned is they loved it. The proof is in the www.history.org.uk/resources/ from their visit, the hard work of diaries they produced. Above is primary_resource_8704_7.html liaising over the internet with their one from Lucy. -

031332736X.Pdf

Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War John A. Wagner GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wagner, J. A. (John A.) Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War / John A. Wagner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-313-32736-X (alk. paper) 1. Hundred Years’ War, 1337–1453—Encyclopedias. I. Title. DC96.W34 2006 944'.02503—dc22 2006009761 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright # 2006 by John A. Wagner All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2006009761 ISBN: 0-313-32736-X First published in 2006 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10987654321 To my father, Joseph L. Wagner, who encouraged me to be whatever I wanted to be and worked ceaselessly to give me opportunities to do so. I have begun [this book] in such a way that all who see it, read it, or hear it read may take delight and pleasure in it, and that I may earn their regard. —Jean Froissart, prologue to Chronicles Contents List of Entries ix Guide to Related Topics xiii Preface xxiii Acknowledgments xxvii Chronology: The Hundred -

Henry V Throughout History: the King Has Killed His Heart | 1

Henry V Throughout History: The King Has Killed His Heart | 1 As our journey through the different filmed versions of William Shakespeare’s Henry V continues, we come to a very significant incarnation – Kenneth Branagh’s 1989 film. In 1989, Kenneth Branagh took the task of adapting The Bard’s history play Henry V for the big screen. Like Laurence Olivier before him, Branagh adapted the script, directed the film, and portrayed the title character himself. At the time of the film’s release, fans of Shakespearian cinema may well have already seen Olivier’s version, which presented Henry as a charismatic and adored leader, intended to inspire patriotism to a wartime audience. Audiences may have even witnessed David Gwillim’s darker televised portrayal in 1979. So how does Branagh’s take compare? As the film begins, it’s immediately clear this version of the play will be a solemn and modernised affair. The opening credits slowly appear in blood red text against a pitch-black background. Solemn orchestral music broods in the background. Derek Jacobi plays The Chorus, who delivers his opening monologue in dark modern clothing while wandering through a film studio soundstage filled with unfinished sets. This gets the message across – this is a modern filmic adaptation, not an imitation of what’s come before. From there, we are thrust into the action as Jacobi leads us through a huge black door. The pacey script then rattles through the opening conversion between the Bishop of Ely and the Archbishop of Canterbury at speed. This scene sometimes seems like a dull opening, but here – sped up and staged in a gloomy candle-lit room – feels tense and intriguing. -

Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War

Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War John A. Wagner GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wagner, J. A. (John A.) Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War / John A. Wagner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-313-32736-X (alk. paper) 1. Hundred Years’ War, 1337–1453—Encyclopedias. I. Title. DC96.W34 2006 944'.02503—dc22 2006009761 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright # 2006 by John A. Wagner All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2006009761 ISBN: 0-313-32736-X First published in 2006 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10987654321 To my father, Joseph L. Wagner, who encouraged me to be whatever I wanted to be and worked ceaselessly to give me opportunities to do so. I have begun [this book] in such a way that all who see it, read it, or hear it read may take delight and pleasure in it, and that I may earn their regard. —Jean Froissart, prologue to Chronicles Contents List of Entries ix Guide to Related Topics xiii Preface xxiii Acknowledgments xxvii Chronology: The Hundred -

Showing One's Manhood: the Social Performance of Masculinity

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Showing One’S Manhood: The oS cial Performance Of Masculinity Fayaz Kabani University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kabani, F.(2018). Showing One’S Manhood: The Social Performance Of Masculinity. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5080 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHOWING ONE’S MANHOOD: THE SOCIAL PERFORMANCE OF MASCULINITY by Fayaz Kabani Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2003 Master of Fine Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Nina Levine, Major Professor David Miller, Committee Member Ed Gieskes, Committee Member Rob Kilgore, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Fayaz Kabani, 2018 All Rights Reserved. ii ABSTRACT Contrary to much criticism of the past thirty years that regards Shakespeare’s Prince Hal as the epitome of unfettered Machiavellian subjectivity, Hal should be regarded as a teenaged male navigating the contradictory discourses of early modern masculinity in order to perform an integrated, consistent masculinity for his audience. His acceptance of hegemonic masculinity is complicated by his father Henry IV’s usurpation of the throne. -

Tudor Coins As Bearers of Ideology of a Young Nation State

Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts 2021, 8: 1-27 https://doi.org/10.30958/ajha.X-Y-Z Tudor Coins as Bearers of Ideology of a Young Nation State By Natalya Davidko* Sixteenth century England saw the conception and dissemination of a new ideology aimed at national consolidation and identity formation. Elaborated in philosophical and theological writings, Parliamentary acts and ordinances, underpinned by contemporary literature and art, the new ideology had one more potent but often overlooked vehicle of propagation – the Tudor money, a unique semiotic system of signs encoding in its iconography and inscriptions the abstract principles of the nascent ideology. The article argues for the significance of the political dimension of the coinage in question and suggests possible ideological readings of coins' visual design and their textual component. We also hypothesize that coin symbolism, literary texts professing national values and ideals, and visual art form distinct but inter-complementary domains (numismatics, pictorial art, and poetics) and function as potent tools of propaganda. Introduction The period this paper is concerned with is the Tudor age (1485-1603), which spans a century, is represented by five crowned monarchs and is marked by dramatic changes in all spheres of economic, political, religious, and cultural life. According to historical chronology, the 16th century marks the beginning of the Modern period in the history of England, which is characterized by the transition from feudalism to a new economic order accompanied by sweeping restructuring of industry and agriculture and consequent painful social changes. The distinguishing features of this period are consolidation of absolutism and imperial aspirations of the Crown that resulted in the subjugation of new territories and peoples.