By Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan, and Now to Write the Foreword of Its Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Rukmini Devi Arundale

Rukmini Devi Arundale January 6, 2021 Rukmini Devi Arundale(1904 – 1986) “I was very intuitive from an early age. I responded to people just as I responded to art – through an inner feeling which is difficult to explain. I just felt some things were right and some were not…” Rukmini Devi was born on 29 February 1904 in Madurai of Tamilnadu. She was the first woman in Indian history to be nominated a member of the Rajya Sabha. Rukmini Devi Arundale was an Indian theosophist, dancer, and choreographer of the Indian classical dance form of Bharatnatyam, and an activist for Animal welfare. The most important revivalist of Bharatanatyam from its original ‘sadhir’ style prevalent amongst the temple dancers, the Devadasis, she also worked for the re- establishment of traditional Indian arts and crafts. She was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1956 and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship in 1967. In January 1936, she along with her husband established Kalakshetra, an academy of dance and music, built around the ancient Indian Gurukul system, at Adyar, at Chennai. Today the academy is a deemed university under the Kalakshetra Foundation. She also became very close to Annie Besant and helped her with her work. She went on to become the President of the Theosophical Society after Dr. Besant’s passing and Rukmini Devi herself was an active member of the Theosophical movement. She gave her first performance at the Diamond Jubilee celebrations of the Theosophical Society in 1935. Theosophists hailed her as the World Mother, to her family in Kalakshetra she is Athai (paternal aunt). -

Odissi Dance

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2005 ODISSI DANCE Photo Courtesy : Introduction : KNM Foundation, BBSR Odissi dance got its recognition as a classical dance, after Bharat Natyam, Kathak & Kathakali in the year 1958, although it had a glorious past. The temple like Konark have kept alive this ancient forms of dance in the stone-carved damsels with their unique lusture, posture and gesture. In the temple of Lord Jagannath it is the devadasis, who were performing this dance regularly before Lord Jagannath, the Lord of the Universe. After the introduction of the Gita Govinda, the love theme of Lordess Radha and Lord Krishna, the devadasis performed abhinaya with different Bhavas & Rasas. The Gotipua system of dance was performed by young boys dressed as girls. During the period of Ray Ramananda, the Governor of Raj Mahendri the Gotipua style was kept alive and attained popularity. The different items of the Odissi dance style are Mangalacharan, Batu Nrutya or Sthayi Nrutya, Pallavi, Abhinaya & Mokhya. Starting from Mangalacharan, it ends in Mokhya. The songs are based upon the writings of poets who adored Lordess Radha and Krishna, as their ISTHADEVA & DEVIS, above all KRUSHNA LILA or ŎRASALILAŏ are Banamali, Upendra Bhanja, Kabi Surya Baladev Rath, Gopal Krishna, Jayadev & Vidagdha Kavi Abhimanyu Samant Singhar. ODISSI DANCE RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE CLASSICAL DANCE FORM Press Comments :±08-04-58 STATESMAN őIt was fit occasion for Mrs. Indrani Rehman to dance on the very day on which the Sangeet Natak Akademy officially recognised Orissi dancing -

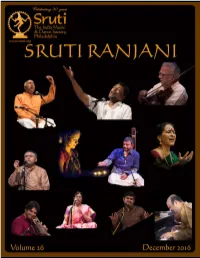

Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan

Table of Contents From the Publications & Outreach Committee ..................................... Lakshmi Radhakrishnan ............ 1 From the President’s Desk ...................................................................... Balaji Raghothaman .................. 2 Connect with SRUTI ............................................................................................................................ 4 SRUTI at 30 – Some reflections…………………………………. ........... Mani, Dinakar, Uma & Balaji .. 5 A Mellifluous Ode to Devi by Sikkil Gurucharan & Anil Srinivasan… .. Kamakshi Mallikarjun ............. 11 Concert – Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan ..... 14 A Grand Violin Trio Concert ................................................................... Sneha Ramesh Mani ................ 16 What is in a raga’s identity – label or the notes?? ................................... P. Swaminathan ...................... 18 Saayujya by T.M.Krishna & Priyadarsini Govind ................................... Toni Shapiro-Phim .................. 20 And the Oscar goes to …… Kaapi – Bombay Jayashree Concert .......... P. Sivakumar ......................... 24 Saarangi – Harsh Narayan ...................................................................... Allyn Miner ........................... 26 Lec-Dem on Bharat Ratna MS Subbulakshmi by RK Shriramkumar .... Prabhakar Chitrapu ................ 28 Bala Bhavam – Bharatanatyam by Rumya Venkateshwaran ................. Roopa Nayak ......................... 33 Dr. M. Balamurali -

One 1 Mark Question. One 4 Mark Question. One 6 Mark Question

10. Rukmini Devi Arundale. One 1 mark question. One 4 mark question. One 6 mark question. Content analysis About Rukmini Devi Arundale. Born on 29‐02‐1904 Father Neelakantha StiSastri Rukmini Devi Arundale Rukmini Devi Liberator of classical dance. India’s cultural queen. Rukmini Devi Fearless crusader for socilial c hange. Champion of vegetarianism. Andhra art of vegetable-dyed Kalmakari Textile crafts like weaving silk an d cotton a la (as prepared in) Kanchipuram Banyan tree at Adyar Rukmini Devi The force that shaped the future of Rukmini Devi Anna Pavlova Anna Pavlova Wraith-like ballerina (Wraith-like =otherworldly) Her meeting with Pavlova. First meeting : In 1924, in London at the Covent Gardens. Her meeting with Pavlova. Second meeting: Time : At the time of annual Theosophical Convention at Banaras. Place : Bombay - India. The warm tribute of Pavlova Rukmini Devi: I wish I could dance like you, but I know I never can. The warm tribute of Pavlova Anna Pavlova:NonoYoumust: No, no. You must never say that. You don’t have to dance, for if you just walk across the stage, it will be enouggph. People will come to watch you do just that. Learning Sadir. She learnt Sadir, the art of Devadasis . Hereditary guru : Meenakshisundaram Pillai. Duration: Two years. First performance At the International Theosophical Conference Under a banyan tree In 1935. reaction Orthodox India was shocked . The first audience adored her revelatory debut. The Bishop of Madras confessed that he felt like he had attended a benediction. Liberating the Classical dance. Changes made to Sadir. Costume and jewellery were of good taste. -

Visionary Craft

Chennai • CITY EDITION • FEBRUARY 28, 2020 Arts | Dance | Music | Movies www.thehindu.com/FridayReview Theatre | Review | History & Culture | Faith Lakshmi Viswanathan CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC of the soul to the Highest. It needs the sential feature of India’s art is that it is same devotion, the same great flights A leap year child, founded on a spiritual outlook,” she et me begin by paying my of imagination that produces reli Rukmini Devi said. She often emphasised that “ homage to the founder of gious feeling. Added to these are the spirituality” was above religion. “In Kalakshetra, Rukmini De creative spirit which, blossoming out Arundale was also a India there is no religion apart from vi Arundale. I knew her, of the artist produces great works of nonpolitical activist our daily lives.” interacted with her, and art. Think of some of the great tem in my own modest way, ples and the bronze images of South and a woman known Path-breaking experiments Lhelped her with some of her thought India. These were not made by so for her refined Such clear thinking moulded her ful ventures like the Kalakshetra Jour- phisticated people… they may not vision for dance and thus was born nal. I admired her as a leader of In even be able to speak to us about ab aesthetic sense the institution Kalakshetra. She was dian culture, a thinker and a creative stract philosophy… nevertheless they the first to understand the value of a artiste. She knew that the arts have to were the people who created master school for dance. -

The High Court of Orissa,Cuttack List of Business for Friday the 19Th February 2021 Chief Justice's Court (2Nd Floor)

SUPPLEMENTARY LIST THE HIGH COURT OF ORISSA,CUTTACK LIST OF BUSINESS FOR FRIDAY THE 19TH FEBRUARY 2021 CHIEF JUSTICE'S COURT (2ND FLOOR) AT 10:30 AM THE HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE AND THE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE B. P. ROUTRAY CRIMINAL APPLICATINOS & MOTIONS. THIS BENCH WILL FUNCTION THROUGH HYBRID ARRANGEMENT (VIRTUAL/PHYSICAL MODE. Learned Counsel desirous to appearing through Virtual Mode shall intimate the name, item number, case details etc. to the Court Master through Mobile no. 8763760499 between 8.00 P.M. to 10.00 P.M. on the previous date of the hearing of the case. LEARNED ADVOCATES ARE REQUESTED TO SUBMIT THE MEMOS FOR URGENT LISTING OF MATTERS FIRST TO THE D.R.(JUDICIAL), AND ONLY WHERE THE D.R.(JUDICIAL) HAS COMMUNICATED THAT THE REQUEST HAS BEEN DECLINED OR THE DATE GIVEN IS NOT CONVENIENT FOR SOME REASONS, SHOULD THE MATTERS BE MENTIONED ORALLY BEFORE THE BENCH OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE OR SUCH BENCH ASSIGNED FOR THE PURPOSE. FOR THE ORAL MENTIONING BEFORE THE DIVISION BENCH IN CHIEF JUSTICE’S COURT, LEARNED ADVOCATES WILL FIRST OBTAIN FROM THE COURT MASTER BETWEEN 9.30 A.M. AND 10.15 A.M. ON ALL WORKING DAYS, OVER PHONE NO.8763760499, A MENTIONING MATTER (MM) NUMBER. IN MATTERS OTHER THAN FRESH ADMISSION MATTERS, THE LEARNED ADVOCATES WILL FURNISH TO THE COURT MASTER ON e-mail ID- [email protected] PROOF OF INTIMATION OF THE MENTIONING TO LEARNED COUNSEL FOR THE OPPOSITE PARTIES. WHEN THE COURT OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE ASSEMBLES, THE MENTIONING MATTERS WILL BE CALLED OUT SERIAL WISE.) (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST WILL BE TAKEN UP FIRST.) (THIS BENCH WILL RISE AT 12.50 P.M.AND MAY FUNCTION AGAIN AFTER LUNCH.) NUMBER OF SLOTS AND RESPECTIVE V.C. -

IRDAI Cracks Down on Reliance Health

EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE THE HINDU DELHI FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 2019 BUSINESS 15 EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE market watch 07-11-2019 % CHANGE Sensex dddddddddddddddddddddd 40,654 ddddddddddddddd0.45 IRDAI cracks down on Reliance Health US Dollardddddddddddddddddddd 70.97 ddddddddddddddd0.00 Gold ddddddddddddddddddddddddddd 38,930 ddddddddddddd-0.18 Brent oil ddddddddddddddddddddd 62.52 ddddddddddddd-0.53 Regulator asks health insurer to stop selling policies over solvency worries N. Ravi Kumar nancial assets to RGICL with nuine claims will continue to NIFTY 50 HYDERABAD effect from November 15. be duly honoured.” PRICE CHANGE The Insurance Regulatory “Till that time, RHICL had However, Reliance Capi Adani Ports. ............. ..... 390.45. ....... -0.55 and Development Authority been prohibited from using tal, the promoter of Reliance Asian Paints. ........... -

FINE ARTS ART and CULTURE ‡ Bhangra (Punjab) - Folk Dance of Harvest Season, Coinciding with the Festival of Baisakhi

78 FINE ARTS ART AND CULTURE ‡ Bhangra (Punjab) - folk dance of harvest season, coinciding with the festival of Baisakhi. ‡ Lalit Kala Academy was set up in 1954 at New Delhi. ‡ Tamasha (Maharashtra) - Nautanki (U.P.), Garba ‡ Sangeet natak Academy was established in 1953 at (Gujarat), Chhow (Orissa, Bihar). New Delhi. Its function is to conduct survey ‡ There are two forms of music in India - Carnatic and research of different art forms in India. Hindustani. ‡ Sahitya Academy was established in 1954 at New ‡ Sama Veda deals with music. Delhi. Its aim is to encourage production of high ‡ Purandaradas gave shape and form to Carnatic class literature in several languages of India. music. ‡ The National Book Trust of India was set up in ‡ The trinity of Carnatic music is Thyagaraja, Syama 1957. Shastri and Muthuswami Dikshitar. ‡ ASI - Archaeological Survey of India - was established in 1861. Its headquarters is in New Names Associated with Indian Music: Delhi. ‡ Ustad Alla Rakha - A master of the Tabla. ‡ Indian Council for Cultural Relations was established ‡ Bala Murali Krishna - A singer of Carnatic music. in 1950, and it strives to promote and to strengthen cultural relations and mutual understanding between ‡ Bhim Sen Joshi - A Hindustani singer. India and other countries. The Council administers ‡ Pt. Hari Prasad Chaurasya - Flute player. the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for the promotion of ‡ Pt. Jasraj - Famous singer of Hindustani music. peace and international understanding. ‡ Parveen Sulthana - Hindustan style singer. ‡ NSD - National School of Drama - was set up in 1959 in Delhi. ‡ Neralathu Ramapothuval - Sopanam. ‡ Dances : There are two main branches of Indian ‡ M.S.Subha Lakshmi - Carnatic music. -

Chapter 1 Uday Shankar and Locating Modernity

CHAPTER 1 UDAY SHANKAR AND LOCATING MODERNITY In 1920, a twenty year old, handsome Indian student arrived in London to study painting at the Royal College of Art. Three years later, he made his debut at Covent Garden alongside the legendary Russian ballet dancer, Anna Pavlova, although—quite remarkably—until a few months earlier, he had little to no dance experience. His audiences in England, France, and the United States nevertheless thought he was very talented at what he did. The dancer invented a new style of dance, which purportedly represented Indian culture; his dance looked “foreign” enough that nobody doubted his claim. In the late 1920s, the dancer returned to India, and demonstrated his new style to his fellow compatriots. Most of his compatriots did not care for this new style, but a few prominent figures encouraged him to continue with what he was doing. His family and friends also supported him; some of them even joined his dance troupe as dancers and musicians, including his youngest brother, twenty years his junior. The troupe then returned to Paris. Meanwhile, India was nearing the end of its dramatic transition from a British imperial colony to a newly independent nation. When the dancer returned to settle in India in the late 1930s, he immersed himself in the current debates over India’s future identity and culture. Most people, who believed the essence of Indian culture could be found in its ancient traditions, were looking to the past for the “real” definition of national culture and identity. The dancer, however, proposed that his invented style and eclectic approach to art defined India’s culture instead. -

It Will Be My Greatest Happiness to Know That in Its Own Humble Way, Kalakshetra Is Helping to Make More Beautiful, More A

"It will be my greatest happiness to know that in its own humble way, Kalakshetra is helping to make more beautiful, more artistic, the lives of all - that in the education of the young, creative reverence for that spirit of the beautiful which knows no distinction of race, nation or faith has a pre-eminent place..." Rukmini Devi Arundale INTRODUCTION RUKMINI DEVI COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS BHARTANATYAM REPERTORY CARNATIC MUSIC VISUAL ARTS MAP OF KALAKSHETRA PART TIME COURSES SCHOOLS MUSEUM LIBRARIES, ARCHIVES AND PUBLICATIONS PERFORMANCE SPACES CONTACT DETAILS ABOUT OUR FOUNDER RUKMINI DEVI ARUNDALE 1904 -1986 ukmini Devi was born in the temple town of Madurai in Rthe erstwhile Madras Presidency, now in Tamil Nadu. She spent her early years there along with her eight siblings. Her father Neelakanta Sastry who was very “forward thinking” initiated the family into the philosophy of the Theosophical Society, which freed religion from superstition. She grew up in the environment of the Theosophical Society, influenced and inspired by people like Dr. Annie Besant, Dr. George Sydney Arundale, C. W. Leadbeater and other thinkers and theosophists of the time. In 1920, she married Dr. George Sydney Arundale. Although they faced a great deal of opposition from the conservative society of Madras, they stayed firm in their resolve and worked together in the years that followed. KALAKSHETRA'S ORIGINS n August 1935, Rukmini Devi along with her husband Dr. IGeorge Sydney Arundale and her brother Yagneswaran met with a few friends to discuss a matter of great importance to her – the idea of establishing an arts centre where some of the arts, particularly music and dance, could thrive under careful guidance. -

Abhinaya in Bharatanatyam

PAPER 6 DANCE IN INDIA TODAY, DANCE-DRAMAS, CREATIVITY WITHIN THE CLASSICAL FORMS, INDIAN CLASSICAL DANCE IN DIASPORA (USA, UK, EUROPE, AUSTRALIA, ETC.) MODULE 19 THE EARLY FEMALE GURUS AND DANCERS OF BHARATANATYAM From early 1900 A D, some brave girls and their families started a journey, going where earlier it was a great taboo to go. The courage, conviction and love for dance prompted them to venture on a path which at that point had no direction and was beyond worldly gains. Also in such a tumultuous time, to be born to that tradition was really tough. We need to know, understand and get inspired by these women, due to whom millions are not only learning Bharatanatyam, but it has given dignity and purpose to the art. Here we study a few of them. SMT. BALASARASWATI Balasaraswati was born in 1918 and died at 1984. She rose on the solo Bharatanatyam horizon through her sheer genius. She belonged to the devadasi tradition and was extremely proud of it, though she was never initiated into any temple service. The only dancer to be conferred the prestigious Sangitha Kalanidhi title; she reacted sharply to compartmentalizing the dance into sacred and profane water-tight divisions. For Bala, Shringara / �रĂगार was an all- 1 encompassing mood which included all the other moods. In 1975, speaking at the Annual Conference of Tamil Sangam, Bala made the famous statement, "In Bharatanatyam, the shringara we experience is never carnal, never, never!" Bala came from a home where musicians like Dharmapuri Subbarayar / धरमऩुरी, Tiruvottiyur Tyagier, Hayagrivachari / हयाग्रिवाचारी (from Dharwad / धारवाड़), Govindaswamy Pillai, Ariyakkudi Ramanuja lyengar were frequent visitors, who came to meet and listen to Bala's grandmother, the inimitable Dhanammal, the veena player.