July 1970 ~,' -Rjfl, "

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOYALTY in the WORKS of SAINT-EXUPBRY a Thesis

LOYALTY IN THE WORKS OF SAINT-EXUPBRY ,,"!"' A Thesis Presented to The Department of Foreign Languages The Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia In Partial Fulfillment or the Requirements for the Degree Mastar of Science by "., ......, ~:'4.J..ry ~pp ~·.ay 1967 T 1, f" . '1~ '/ Approved for the Major Department -c Approved for the Graduate Council ~cJ,~/ 255060 \0 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to extend her sincere appreciation to Dr. Minnie M. Miller, head of the foreign language department at the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia, for her valuable assistance during the writing of this thesis. Special thanks also go to Dr. David E. Travis, of the foreign language department, who read the thesis and offered suggestions. M. E. "Q--=.'Hi" '''"'R ? ..... .-.l.... ....... v~ One of Antoine de Saint-Exupe~J's outstanding qualities was loyalty. Born of a deep sense of responsi bility for his fellowmen and a need for spiritual fellow ship with them it became a motivating force in his life. Most of the acts he is remeffibered for are acts of fidelityo Fis writings too radiate this quality. In deep devotion fo~ a cause or a friend his heroes are spurred on to unusual acts of valor and sacrifice. Saint-Exupery's works also reveal the deep movements of a fervent soul. He believed that to develop spiritually man mQst take a stand and act upon his convictions in the f~c0 of adversity. In his boo~ UnSens ~ la Vie, l he wrote: ~e comprenez-vous Das a~e le don de sol, le risque, ... -

The Archetype of a Cultural Hero in the Works of A. De Saint-Exupery (Based on “Southern Mail”, “Night Flight” and “Wind, Sand and Stars”)

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 5 (2016 9) 1074-1080 ~ ~ ~ УДК 82-3 The Archetype of a Cultural Hero in the Works of A. De Saint-Exupery (Based on “Southern Mail”, “Night Flight” and “Wind, Sand and Stars”) Sofiia A. Andreeva and Yana G. Gerasimenok* Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia Received 17.02.2016, received in revised form 16.03.2016, accepted 02.04.2016 This article is devoted to the analysis of a pilot’s character in the works of A. de Saint-Exupery in the context of mythopoetics and the archetype of a cultural hero. The theme of aviation and the character of a pilot are the main elements of Saint-Exupery’s poetics. Being a professional pilot he described true events and created a heroic and mainly mythologized character of a pilot. In his works there are such functions of a cultural hero as fighting with nature or mythical beasts, breaking new ways, formation of human society. There are also motifs of initiation, magic transition to another world, death and rebirth. Such archetypic spaces as desert, night, sky/earth are connected with the character of a pilot. Keywords: archetype, aviation, French literature, mythopoetics, Saint-Exupery. DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-2016-9-5-1074-1080. Research area: philology. Introduction into the problem Due to the dangerous and unusual nature of this For many centuries the idea to conquer the profession romanticization of pilots in the first sky has been concerning the minds of people. half of the 20th century has led to the fact that They created drawings of flying machines, the pilot’s character became mythologized and conducted experiments, dreams of flying were acquired the features of exclusivity. -

Ar.Itorne DE Sarrvr- Exupf Nv

Ar.itorNE DE Sarrvr-Exupf nv Born: Lyon, France June 29, 1900 Died: Near Corsica July3l ,7944 Throughhis autobiographicalworhs, Saint-Exupery captures therra of earlyaviation uith his$rical prose and ruminations, oftenrnealing deepertruths about the human condition and humanity'ssearch for meaningand fulfillrnar,t. teur" (the aviator), which appeared in the maga- zine LeNauired'Argentin 1926.Thus began many of National Archive s Saint-Exup6ry's writings on flying-a merging of two of his greatestpassions in life. At the time, avia- Brocnaprrv tion was relatively new and still very dangerous. Antoine Jean-Baptiste Marie Roger de Saint- The technology was basic, and many pilots relied Exup6ry (sahn-tayg-zew-pay-REE)rvas born on on intuition. Saint-Exup6ry,however, was drawn to June 29, 1900, in Lyon, France, the third of five the adventure and beauty of flight, which he de- children in an aristocratic family. His father died of picted in many of his works. a stroke lvhen Saint-Exup6ry was only three, and Saint-Exup6rybecame a frontiersman of the sky. his mother moved the family to Le Mans. Saint- He reveled in flying open-cockpit planes and loved Exup6ry, knor,vn as Saint-Ex, led a happy child- the freedom and solitude of being in the air. For hood. He wassurrounded by many relativesand of- three years,he r,vorkedas a pilot for A6ropostale, a ten spent his summer vacations rvith his family at French commercial airline that flew mail. He trav- their chateau in Saint-Maurice-de-Remens. eled berween Toulouse and Dakar, helping to es- Saint-Exup6ry went to Jesuit schools and to a tablish air routes acrossthe African desert. -

The Little Prince

The Little Prince [Illustrated Edition] By Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Translated by Katherine Woods Illustrated & Re-Produced by A. Saint-Exupéry & Murat Ukray ILLUSTRATED & PUBLISHED BY e-KİTAP PROJESİ & CHEAPEST BOOKS www.cheapestboooks.com www.facebook.com/EKitapProjesi Copyright, 2015 by e-Kitap Projesi Istanbul ISBN: 978-9635-2739-59 All rights reserved. No part of this book shell be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or by any information or retrieval system, without written permission form the publisher. Contents Contents Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, officially Antoine Marie Jean-Baptiste Roger, comte de Saint Exupéry (29 June 1900 – 31 July 1944) was a French aristocrat, writer, poet, and pioneering aviator. He became a laureate of several of France's highest literary awards and also won the U.S. National Book Award. He is best remembered for his novella The Little Prince (Le Petit Prince) and for his lyrical aviation writings, including Wind, Sand and Stars and Night Flight. Saint-Exupéry was a successful commercial pilot before World War II, working airmail routes in Europe, Africa and South America. At the outbreak of war, he joined the French Air Force (Armée de l'Air), flying reconnaissance missions until France's armistice with Germany in 1940. -

<I>Life of Pi</I>: Perspectives on Truth

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Department of English, Literature, and Modern English Seminar Capstone Research Papers Languages 4-15-2013 Life of Pi: Perspectives on Truth Sarah Morse Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ english_seminar_capstone Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Morse, Sarah, "Life of Pi: Perspectives on Truth" (2013). English Seminar Capstone Research Papers. 19. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/english_seminar_capstone/19 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Seminar Capstone Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Life of Pi: Perspectives on Truth Sarah Morse Dr. Deardorff Senior Seminar 15 April 2013 Morse 1 Narrative and story predicate perspective. Stories that frame narration change perspective into a literary device. This narrative form enriches as it challenges the reader’s perspective on truth, often confronting readers with an ageless dilemma: is this narrator trustworthy? Framed narration also introduces the idea that truth is multi-faceted. Truth manifests itself through multiple perspectives. This is not to say that every perspective tells the truth, but it is to suggest that multiple perspectives provide a more comprehensive understanding of the truths embedded in a story. Perspectives give stories, life, and truth dimension.1 Yann Martel’s Life of Pi is a story on perspectives. Martel utilizes framed narrative to relate one boy’s castaway experience on a lifeboat with a 250 lb. -

If There Were a European Counterpart to Charles Lindbergh, It Would Be Antoine De Saint-Exupéry

CHAPTER 12 CULTIVATING THE GARDEN: ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPÉRY AND THE NOBLE STRUGGLE If there were a European counterpart to Charles Lindbergh, it would be Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. While Saint-Exupéry’s ability to poeticize flight preceded (and arguably exceeded) Lindbergh’s, both men personified transcendence in ways that were to be unequaled by any other pilot. Contemporaries and acquaintances, the men earned their pilot licenses within a year of each other,1 received military flight instruction, and made a living delivering mail at a time when doing so was largely considered to be “the next thing to suicide”.2 Both men flew in far-flung locations, volunteered their flying services in World War II, expressed faith in the transformative ability of flight, and both came to personify national and cultural ideals. Even though the men began their flying careers in relative anonymity – Lindbergh obscured by the figure of Richard Byrd and Saint-Exupéry by the popularity of French aerial sensation, Jean Mermoz – their approaches to flight and writing differed sharply. Before turning to life narrative, Saint-Exupéry was already well known for his fiction, which was loosely based on his experiences flying for Aéropostale.3 His autobiographical work, Terre des Hommes, published in English as Wind, Sand and Stars (1939), was less a methodical attempt at self-representation than it was an effort to appease French publishers to whom Saint-Exupéry was in debt. Finding himself in financial trouble and suffering from serious injuries incurred from a failed takeoff in Guatemala during a “goodwill 1 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in 1921 and Lindbergh in 1922. -

Antoine De Saint-Exupéry Writer, Poet and Pioneering Aviator

60 I Time Pieces Deluxe I Sky icon I 61 ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPÉRY Writer, Poet and Pioneering Aviator The Little Prince “To be a man is to be responsible: to be ashamed There have been few stories published that have captured the hearts of miseries you did not cause; to be proud of your and minds of children and adults quite like Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s comrades' victories; to be aware, when setting one stone, Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince), which recently celebrated its 70th that you are building a world.” anniversary. It is an enchanting tale of a pilot stranded in the desert meeting a young prince, who has travelled to earth from his home on a small asteroid in search of friendship and greater understanding. As - Antoine de Saint-Exupery (Livre de Poche n°68, p. 59) the pilot attempts to repair his downed plane, the little prince shares the story of his life with him, recounting tales of other planets visited and odd people encountered. Originally intended as a children’s book, the story tenderly unfolds, revealing many profound and idealistic observations about life and human nature. One of the novella’s most frequently used quotes is from one of the fox’s many lessons, “On ne voit bien qu'avec le cœur. L'essentiel est invisible pour les yeux.” (“One sees clearly only with the heart. What is essential is invisible to the e ye .” ) Written in the author’s native French, and then translated into English by Katherine Woods, The Little Prince was first published in the United States in April 1943 by Reynal & Hitchkock. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION in This Chapter, the Writer Discusses The

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION In this chapter, the writer discusses the introduction of the research. This chapter is divided into five sections, namely research background, research problem, research objectives, research benefits, and definition of terms. 1.1 Research Background “Perhaps the greatest social service that can be rendered by anybody to the country and to mankind is to bring up a family.” (Shawn, 2005, p. 25) Indonesia faces the complex challenges in entering globalization era. Internally, we are still not capable to get out from multidimensional (economic, social, political, and cultural) crisis. Externally, Indonesia faces the reality of global competition worldwide. The main key lies in the quality of human resources. Indonesia’s improvement in 10 -20 years ahead is determined by today's young generation. The highlighted cases about child and adolescent delinquency are being unfinished homework for adults in Indonesia. For instance, throughout the year 2013, a total of 255 cases of violence had occurred that killed 20 students all over Indonesia. Secretary of KNPAI, Rita (in KNPAI, 2016), claims that by 2014, KNPAI receives 2,737 cases or 210 cases per month including cases of violence by abusers of children who turned out to rise up to 10 percent. In association with the data from the Indonesia Commission for Child Protection (Komisi Perlindungan Anak Indonesia Daerah, KPAID) Branch Kalimantan, during 2015, the children as abusers, including a brawl between students, will increase by approximately 12-18 percent. Here the seeds of radicalism grew. Not only the increasing of children violence in 2011 to 2015, the data states that the children prostitution increasing prevalently (Putra, 2015). -

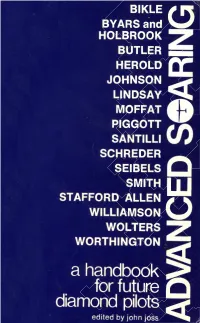

ADVANCED SOARING a Handbook for Future Diamond Pilots

ssof uqof Aq pajjpa NOlONIHiaOM suanoM NOSIAIVITIIM N311V QUOddVlS H1IIAIS 8138138 U3Q3UH9S milNVS llOOOId IVddOIAI AVSQNH NOSNHOf XOOUS1OH PUB SHVAfl ADVANCED SOARING a Handbook for future diamond pilots edited by John joss Some notes on this book: The text was set in Press Roman 11/12 on the IBM MTSC. The display type is Century. The book was designed and composed by Graphic Production of Redwood City, California, and printed by The George Banta Company, Inc., of Mcnasha, Wisconsin. The Soaring Press P.O. Box 960 Los Altos, California 94022 U.S.A. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written per mission from the Publisher. Copyright © 1974 by John Joss All rights reserved First Edition 1974 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 74-18760 Printed in the United States of America 11 DEDICATION To all the authors represented in this volume, who have taught me almost all I know about advanced soaring. 111 CONTENTS Illustrations................................... \i Introduction .................................. xv I. BASICS I. Advanced Soaring ...................... 3 An approach that works Ed llYiirs and Bill llolbrook 2 Starting at Chaveiviy. 1959 ............... 15 How is your technical French? George Mojfat 3. Soaring Tips. .......................... 27 Some 'never forget' pointers Richard E. Schreder 4. Thermaling ........................... 33 The art of going up R. Bromley 5. Wave Soaring .......................... 45 The techniques that really work Jack Harmon 6. Into Waves from Thermals ................ 59 A safer route to altitude Alcide Santilli 7. Cross-Country Weather .................. 75 Air-mass type and season favoring long flights Charles V. -

My Father, an Airline Pilot, Loves Airplanes More Than Anything

My father, an airline pilot, loves airplanes more than anything. Determined to share his love of flying with me, he gave me his favorite book for my eleventh birthday: The Little Prince, by French pilot and author Antoine de Saint Exupéry.1 I read it immediately and cried at the end. No book had ever made me so sad, though I sensed that I did not quite understand its complexity. At the sunny kitchen table, I looked at the black-and-white image of the author’s face on the back flap and wanted to connect with him, longed to understand why he had written such a sad ending, wondered what he had meant to say. These questions began my collection. To find answers, I set about searching for Saint Exupéry’s other five books, which were listed in the front of The Little Prince. My collection started with English-language editions of Saint Exupéry’s works pilfered from my father’s bookshelf while he kindly looked the other way. I started a journal of my favorite quotations, ones that I thought best expressed the beauty of flying or the tragedy of war; from Saint Exupéry I learned that “what is essential is invisible to the eyes.” For my twelfth birthday, I received a biography of Saint Exupéry for my very own, and discovered that my favorite author had never learned to speak English. I knew then that I could never truly understand him without speaking his language. After persuading my parents to drive me to the local Borders, I acquired the French edition of The Little Prince, laid the two editions side by side, and tried to puzzle out the French. -

1 Antoine De Saint Exupéry

Antoine de Saint Exupéry: Pilot, Author, Friend Rose Berman February 1, 2017 My father, an airline pilot, is never happier than when he’s in the cockpit. Determined to share his love of flying with me, he gave me his favorite book for my eleventh birthday: The Little Prince, by French pilot and author Antoine de Saint Exupéry.1 I read it immediately and cried at the end. No book had ever made me so sad, though I sensed that I did not quite understand its complexity. At the sunny kitchen table, I looked at the black-and-white image of the author’s face on the back flap and wanted to connect with him, longed to understand why he had written such a sad ending, wondered what he had meant to say. These questions began my collection. To find answers, I set about searching for Saint Exupéry’s other five books, which were listed in the front of The Little Prince. My collection started with English-language editions of Saint Exupéry’s works pilfered from my father’s bookshelf while he kindly looked the other way. I started a journal of my favorite quotations, ones that I thought best expressed the beauty of flying or the tragedy of war; from Saint Exupéry I learned that “what is essential is invisible to the eyes.” For my twelfth birthday, I received a biography of Saint Exupéry for my very own, and discovered that my favorite author had never learned to speak English. I knew then that I could never truly understand him without speaking his language. -

Antoine De Saint-Exupery - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Antoine de Saint-Exupery - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Antoine de Saint-Exupery(29 June 1900 – 31 July 1944) Antoine Marie Jean-Baptiste Roger, comte de Saint Exupéry was an aristocrat French writer, poet and pioneering aviator. He became a laureate of several of France's highest literary awards and also won the U.S. National Book Award. He is best remembered for his novella The Little Prince (Le Petit Prince) and for his lyrical aviation writings, including Night Flight and Wind, Sand and Stars. He was a successful commercial pilot before World War II, working airmail routes in Europe, Africa and South America. At the outbreak of war he joined the Armée de l'Air (French Air Force), flying reconnaissance missions until France's armistice with Germany in 1940. After being demobilized from the French Air Force he voyaged to the United States to convince its government to quickly enter the war against Nazi Germany. Following a 27-month hiatus in North America during which he wrote three of his most important works, he joined the Free French Air Force in North Africa although he was far past the maximum age for such pilots and in declining health. He disappeared over the Mediterranean on his last assigned reconnaissance mission in July 1944, and is believed to have died at that time. Prior to the war he had achieved fame in France as an aviator. His literary works, among them The Little Prince, translated into over 250 languages and dialects, propelled his stature posthumously allowing him to achieve national hero status in France.