1 Antoine De Saint Exupéry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfil Usuarios Colombia

PROCESO DE PRIVATIZACIÓN DE AEROLÍNEAS ARGENTINAS Aportado por: Miriam Vanesa Quintans - [email protected] Autor: Quintans, Miriam Vanesa INTRODUCCIÓN: El presente trabajo refleja los acontecimientos acaecidos en la última parte de la historia de Aerolíneas Argentinas, ya que por su significación, han producido un cambio tan profundo como perjudicial para el estado de la empresa. Para concatenar la cuantiosa sucesión de hechos hemos decidido tomar el eje de tiempo y dar los hechos sobresalientes a modo de diario de una sola historia conjuntamente con el análisis de los mismos. Como podrá apreciarse por la simple lectura la historia está plagada de idas y venidas de todos los actores intervinientes y ha condicionado la empresa a futuro en función de mejoras que aún no se aprecian. Desde la perspectiva de ciudadanos comunes hemos sentido la perdida de algo que nos enorgullecía y que ha sido cambiado en pos de un fin utilitario del que poco se ha cumplido. El análisis de los hechos ha sido hecho tomando como base el estado en que la empresa se encontraba en el momento de ser privatizada y su potencial. De esto se desprende que el camino recorrido hubiera podido ser muy distinto si no se hubiera actuado con la precariedad y mezquindad con la que se lo hizo. 1) RELATO DE LOS ACONTECIMIENTOS 1.1) Antes de la venta • El primer antecedente de Aerolíneas Argentinas se remonta a 1929, cuando se crea Aeroposta, el correo aéreo por el que pasan los franceses Jean Mermoz y Antoine de Saint- Exupéry, autor de "El principito". -

LOST with a Good Book

The Lost Code: BYYJ C`1 P,YJ- LJ,1 Key Literary References and Influ- Books, Movies, and More on Your Favorite Subjects Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad CAS A CONR/ eAudiobook LOST on DVD A man journeys through the Congo and Lost Complete First Season contemplates the nature of good and evil. There are several references, especially in relation to Lost Season 2: Extended Experience Colonel’s Kurtz’s descent toward madness. Lost Season 3: The Unexplored Experience Lost. The Complete Fourth Season: The Expanded The Stand by Stephen King FIC KING Experience A battle between good and evil ensues after a deadly virus With a Good Book decimates the population. Producers cite this book as a Lost. The Complete Fifth Season: The Journey Back major influence, and other King allusions ( Carrie , On Writing , *Lost: Complete Sixth & Final Season is due for release 8/24/10. The Shining , Dark Tower series, etc.) pop up frequently. The Odyssey by Homer FIC HOME/883 HOME/ CD BOOK 883.1 HOME/CAS A HOME/ eAudiobook LOST Episode Guide Greek epic about Odysseus’s harrowing journey home to his In addition to the biblical episode titles, there are several other Lost wife Penelope after the Trojan War. Parallels abound, episode titles with literature/philosophy connections. These include “White especially in the characters of Desmond and Penny. Rabbit” and “Through the Looking Glass” from Carroll’s Alice books; “Catch-22”; “Tabula Rosa” (philosopher John Locke’s theory that the Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut FIC VON human mind is a blank slate at birth); and “The Man Behind the Curtain” A World War II soldier becomes “unstuck in time,” and is and “There’s No Place Like Home” ( The Wonderful Wizard of Oz ). -

L'envol Des Pionniers

LA PISTE des GÉANTS in MONTAUDRAN L’Envol des Pionniers: A legendary site Press contact: L’Envol des Pionniers Florence Seroussi +33 (0)6 08 96 96 50 [email protected] Toulouse Métropole Aline Degert Maugard +33 (0)5 67 73 88 41/+33 (0)7 86 52 56 53 [email protected] [email protected] www.lenvol-des-pionniers.com PRESS KIT § A FLAGSHIP FACILITY FOR A HISTORIC SITE La Piste des Géants is a cultural site integrated in an ambitious urban project being launched by Toulouse Métropole in Montaudran, historic birthplace of aeronautics. Devised around the runway used for takeoff by the pioneers of civil aviation, La Piste des Géants comprises several facilities: Les Jardins de la Ligne, open in June 2017, a large landscaped itinerary evoking the lands over which the pioneers of La Ligne flew; La Halle de La Machine, a contemporary structure that houses La Machine Street Theatre Company’s ‘Bestiary’ since November and L’Envol des Pionniers, in the site’s rehabilitated historic buildings. In order to do honour to and make known the amazing saga of Toulouse that witnessed the birth of civil aviation with the first flight by Latécoère which took off from Toulouse-Montaudran, then L’Aéropostale and finally Air France, Jean-Luc Moudenc, Mayor of Toulouse, President of Toulouse Métropole, wished to have the historical buildings around the legendary runway rehabilitated. In partnership with the Pioneers’s descendants and many associations, L’Envol des Pioneers, a facility dedicated to the story of aeronautics, was created and was inaugurated on 20 December 2018, 100 years almost to the day after the inaugural flight to Barcelona. -

• La Poste Dans Les Airs E

FICHE PÉDAGOGIQUE bie nv e n u • La Poste dans les airs e a u m e u é Du pigeon à l’Aéropostale s La poste aérienne naît de l’urgence et du besoin impérieux de communiquer avec l’extérieur lors du siège de Paris pendant la guerre franco-allemande de 1870-71. La voie des airs est alors une des seules praticables, et le courrier s’envole par ballons et pigeons voyageurs. Dans les années 1910, les débuts de l’aviation ouvrent une ère nouvelle pour le transport des correspondances avec l’idéal constant d’un acheminement toujours plus rapide. Ce sera, après la Première Guerre mondiale, la grande épopée de l’Aéropostale aux acteurs légendaires : Mermoz, Saint-Exupéry, Guillaumet... Sans oublier son initiateur Pierre-Georges Latécoère. Cette aventure permet la mise en place d’un service d’exploitation aérien, utilisé par la Poste via différentes compagnies d’Air France à Europ Airpost jusqu’aux années 2000. LE COURRIER DANS LES AIRS : LES PRE- MIÈRES EXPÉRIENCES DE LA POSTE AÉ- RIENNE Ballons montés et pigeons voyageurs : le siège de Paris (20 septembre 1870-28 jan- vier 1871) C´est durant le siège de Paris que naît la première poste aérienne française. La guerre franco-allemande, souhaitée par Bismarck qui y voit l’unité de l’Allemagne, est déclarée le 19 juillet 1870 par Napoléon III dans un contexte diplomatique défavorable à la France. Après la chute de ce dernier à Sedan le 2 septembre 1870 et la proclamation d’un gouvernement républicain de défense nationale, les Prussiens assiègent Paris pour forcer le gouvernement à se Le Jean Bart traîné par les mobiles d’Orléans, se rend au camp de Chilleur, novembre 1870, Louis-Lucien rendre et terminer la guerre. -

An Analysis of Relationship in the Little Prince

An Analysis of Relationship in The Little Prince An Analysis of Relationship in The Little Prince 彰化女中。陳慧倢。二年十三班 彰化女中。王瑋婷。二年十三班 - 1 - PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com An Analysis of Relationship in The Little Prince Ⅰ.Preface Upon the most valuable assets one can possess, the relationship with others is one of them. However, due to the invisibility of interior interaction, it is too often neglected. Fortunately, The Little Prince, published in 1943, took the length and breadth of the world by storm. The significant novel brings the consequence of relationship, which affects numerous people, to light. Relationship is the tie between people. In addition, it is the element that makes every moment variable. Furthermore, relationship is what we have to face in our daily social life. Without a doubt, there are many sorts of relationship. Despite the fact that we consider it arduous to tell which the most vital one is, it is not exaggerating to say that the influences of every sort are deep and profound. Relationship enables us to distinguish our beloved ones from all the millions and millions of others. It is then that the world becomes beautiful and is full of sunshine. Without relationship, it is possible for us to ignore love around us. Without relationship, of whom can we think in the livelong June? With whom can we share wheal and woe? Nevertheless, people usually don’t know how to cherish it, how to create it and where to find it. There’s no denying that The Little Prince is the most representative masterpiece in biding defiance to adults’ prejudice against relationship. -

Bio Antoine Tempe E

(S)ITOR curating differently ANTOINE TEMPÉ 1960 Born in Paris (France) Graduated from HEC Business School, Paris (France) Lives and works in Dakar (Senegal) Solo shows 2016 Addis Foto Fest, Addis Abeba (Ethiopia) | Waa Dakar Cultural Centre Georges Méliès, Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) | Antoine Tempé Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie d’Arles (France), with Omar Victor Diop | (re-)Mixing Hollywood Dak’Art Biennale, OFF, Hôtel Sokhamon, with MIS Wude, Dakar (Senegal) | Théorie des Règnes Sensibles Dak’Art Biennale, Special Projects, Old Court of Justice, Dakar (Senegal) | Débris de Justice Dak’Art Biennale, Contours, Public Utility Transport AFTU, Dakar (Senegal) | Waa Dakar 2015 French Institute, Malabo (Equatorial Guinea) | Dancers Lagos Photo Festival, Lagos (Nigeria) | (re-)Mixing Hollywood Felix Houphouet Boigny Airport, Abidjan (Ivory Coast), Donwahi Foundation | Face to Face 2014 La Rotonde des Arts Contemporains, Abidjan (Ivory Coast) | Faces (new works) 2013 Hôtel Onomo, Dakar (Senegal), with Omar Victor Diop | (re-)Mixing Hollywood Alliance Française, Harare (Zimbabwe), Zinsou Foundation | Let’s dance Infecting the City Public Arts Festival, Capetown (South Africa), Zinsou Foundation | Let’s dance Garden Route Botanical Garden, George (South Africa), Zinsou Foundation | Let’s dance 2012 International Convention Centre, Durban (South Africa), Zinsou Foundation | Let’s dance IFAS, Johannesburg/Soweto (South Africa), Zinsou Foundation | Let’s dance Dak’Art Biennale OFF, French Institute, Dakar (Senegal) | Studio Antoine -

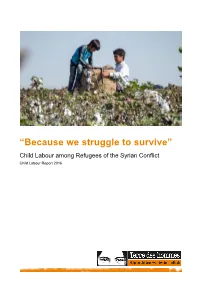

'Because We Struggle to Survive'

“Because we struggle to survive” Child Labour among Refugees of the Syrian Conflict Child Labour Report 2016 Disclaimer terre des hommes Siège | Hauptsitz | Sede | Headquarters Avenue de Montchoisi 15, CH-1006 Lausanne T +41 58 611 06 66, F +41 58 611 06 77 E-mail : [email protected], CCP : 10-11504-8 Research support: Ornella Barros, Dr. Beate Scherrer, Angela Großmann Authors: Barbara Küppers, Antje Ruhmann Photos : Front cover, S. 13, 37: Servet Dilber S. 3, 8, 12, 21, 22, 24, 27, 47: Ollivier Girard S. 3: Terre des Hommes International Federation S. 3: Christel Kovermann S. 5, 15: Terre des Hommes Netherlands S. 7: Helmut Steinkeller S. 10, 30, 38, 40: Kerem Yucel S. 33: Terre des hommes Italy The study at hand is part of a series published by terre des hommes Germany annually on 12 June, the World Day against Child Labour. We would like to thank terre des hommes Germany for their excellent work, as well as Terre des hommes Italy and Terre des Hommes Netherlands for their contributions to the study. We would also like to thank our employees, especially in the Middle East and in Europe for their contributions to the study itself, as well as to the work of editing and translating it. Terre des hommes (Lausanne) is a member of the Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF) that brings together partner organisations in Switzerland and in other countries. TDHIF repesents its members at an international and European level. First published by terre des hommes Germany in English and German, June 2016. -

LOYALTY in the WORKS of SAINT-EXUPBRY a Thesis

LOYALTY IN THE WORKS OF SAINT-EXUPBRY ,,"!"' A Thesis Presented to The Department of Foreign Languages The Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia In Partial Fulfillment or the Requirements for the Degree Mastar of Science by "., ......, ~:'4.J..ry ~pp ~·.ay 1967 T 1, f" . '1~ '/ Approved for the Major Department -c Approved for the Graduate Council ~cJ,~/ 255060 \0 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to extend her sincere appreciation to Dr. Minnie M. Miller, head of the foreign language department at the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia, for her valuable assistance during the writing of this thesis. Special thanks also go to Dr. David E. Travis, of the foreign language department, who read the thesis and offered suggestions. M. E. "Q--=.'Hi" '''"'R ? ..... .-.l.... ....... v~ One of Antoine de Saint-Exupe~J's outstanding qualities was loyalty. Born of a deep sense of responsi bility for his fellowmen and a need for spiritual fellow ship with them it became a motivating force in his life. Most of the acts he is remeffibered for are acts of fidelityo Fis writings too radiate this quality. In deep devotion fo~ a cause or a friend his heroes are spurred on to unusual acts of valor and sacrifice. Saint-Exupery's works also reveal the deep movements of a fervent soul. He believed that to develop spiritually man mQst take a stand and act upon his convictions in the f~c0 of adversity. In his boo~ UnSens ~ la Vie, l he wrote: ~e comprenez-vous Das a~e le don de sol, le risque, ... -

The Essential Is Invisible to the Eye: the Evolution of the Parent Observer

THE ESSENTIAL IS INVISIBLE TO THE EYE: THE EVOLUTION OF THE PARENT OBSERVER by Mary Caroline Parker PART II The question of how schools can help parents experience joy in observing their children led to a quest to identify experiences that can contribute to the awakening of consciousness. Workshops, surveys, discussion, and interviews yielded data that led to some unexpected conclusions about sources of personal transformation. It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye. —The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupery FOUR SURPRISING DISCOVERIES My research over the course of a year’s work with parents had generated a small mountain of notes, surveys, videos, audiotapes, Mary Caroline Parker is the executive director of the Montessori Institute of North Texas (MINT), an AMI teacher training center in Dallas, TX. She holds the AMI primary diploma from Centro de Estudios de Educación in Mexico City, a BA from Smith College, a JD from American University, and an M.Ed in Montessori Integrative Learning from Endicott College. She is a former head of school at Lumin East Dallas Community School and The Barbara Gordon Montessori School (now Waypoint Montes- sori). Parker is a former member of the board of directors of AMI, where she served in the Humanitarian and Child Advocacy position, and she is currently a member of AMI’s Educateurs sans Frontières working group. She serves on the board of Lumin Education, which operates four Montessori programs in low-income Dallas neighborhoods, including two public charter schools and a Montessori-based Early Head Start Center. -

The Archetype of a Cultural Hero in the Works of A. De Saint-Exupery (Based on “Southern Mail”, “Night Flight” and “Wind, Sand and Stars”)

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 5 (2016 9) 1074-1080 ~ ~ ~ УДК 82-3 The Archetype of a Cultural Hero in the Works of A. De Saint-Exupery (Based on “Southern Mail”, “Night Flight” and “Wind, Sand and Stars”) Sofiia A. Andreeva and Yana G. Gerasimenok* Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia Received 17.02.2016, received in revised form 16.03.2016, accepted 02.04.2016 This article is devoted to the analysis of a pilot’s character in the works of A. de Saint-Exupery in the context of mythopoetics and the archetype of a cultural hero. The theme of aviation and the character of a pilot are the main elements of Saint-Exupery’s poetics. Being a professional pilot he described true events and created a heroic and mainly mythologized character of a pilot. In his works there are such functions of a cultural hero as fighting with nature or mythical beasts, breaking new ways, formation of human society. There are also motifs of initiation, magic transition to another world, death and rebirth. Such archetypic spaces as desert, night, sky/earth are connected with the character of a pilot. Keywords: archetype, aviation, French literature, mythopoetics, Saint-Exupery. DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-2016-9-5-1074-1080. Research area: philology. Introduction into the problem Due to the dangerous and unusual nature of this For many centuries the idea to conquer the profession romanticization of pilots in the first sky has been concerning the minds of people. half of the 20th century has led to the fact that They created drawings of flying machines, the pilot’s character became mythologized and conducted experiments, dreams of flying were acquired the features of exclusivity. -

Notions of Self and Nation in French Author

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 6-27-2016 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author- Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Kean University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Kean, Christopher, "Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1161. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1161 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Steven Kean, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 The traditional image of wartime aviators in French culture is an idealized, mythical notion that is inextricably linked with an equally idealized and mythical notion of nationhood. The literary works of three French author-aviators from World War II – Antoine de Saint- Exupéry, Jules Roy, and Romain Gary – reveal an image of the aviator and the writer that operates in a zone between reality and imagination. The purpose of this study is to delineate the elements that make up what I propose is a more complex and even ambivalent image of both individual and nation. Through these three works – Pilote de guerre (Flight to Arras), La Vallée heureuse (The Happy Valley), and La Promesse de l’aube (Promise at Dawn) – this dissertation proposes to uncover not only the figures of individual narratives, but also the figures of “a certain idea of France” during a critical period of that country’s history. -

Textes Recueillis Ed 4 Sans Photos

Emile Barrière 1902 œ 1936 … T V B , avec le sourire … T ém oignages et faits m arquants Fait le 11 avril 2007 Jean-Lin PAUL Emile Auguste Lin Barrière naquit à Toulouse le 15 février 1902. Elève du lycée des Jacobins de Toulouse il y fit de brillantes études montrant un goût particulier pour les sciences et les mathématiques. Puis ce fut l‘école polytechnique (Promotion 22) de 1922 à 1924 après une prépa. au lycée Louis le Grand à Paris, il s‘y fit remarquer par sa vive intelligence, son besoin d‘action, son merveilleux équilibre cérébral et sa philosophie souriante de la vie, car jamais il ne sépara la bonne humeur de la soif de connaître. (Référence 11) Il y fut également capitaine de l‘équipe de Rugby. A sa sortie de polytechnique en 1924 il effectua son service militaire (Lieutenant de réserve) à Avord dans l‘aviation à la RAO 32. La Société Industrielle Des Avions Latécoère œ SIDAL : En 1924 Emile Barrière fût recruté par la société des avions Latécoère à Toulouse, o; il entra comme ingénieur aéronautique au bureau d‘études dirigé par Marcel Moine. Il y fut plus particulièrement chargé de fabrication et de construction. Il y restera 4 ans. Un des plus grands mérites de l'ingénieur M. Moine est d'avoir formé autour de lui une exceptionnelle équipe de mécaniciens et d'ingénieurs qui, à la demande de Didier Daurat, partirent sur tous les points chauds de la Ligne France - Amérique du Sud pour y accomplir des miracles de remises en état ou fonder des ateliers permanents d'entretien à des milliers de kilomètres de Toulouse: Pierre Larcher, Emile Barrière, Gaston Rolland, Paul Jarrier, Georges Piron, André Seguin, Gabriel Deux, combien d'autres allèrent jusqu'au bout du devoir, jusqu'au bout de leur savoir, jusqu'au bout de leur vie.