The Historical Context of the City Wall of Messene: Preconditions, Written Sources, Success Balance, and Societal Impacts*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetics of the Peloponnesean Populations and the Theory of Extinction of the Medieval Peloponnesean Greeks

European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 637–645 Official journal of The European Society of Human Genetics www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Genetics of the peloponnesean populations and the theory of extinction of the medieval peloponnesean Greeks George Stamatoyannopoulos*,1, Aritra Bose2, Athanasios Teodosiadis3, Fotis Tsetsos2, Anna Plantinga4, Nikoletta Psatha5, Nikos Zogas6, Evangelia Yannaki6, Pierre Zalloua7, Kenneth K Kidd8, Brian L Browning4,9, John Stamatoyannopoulos3,10, Peristera Paschou11 and Petros Drineas2 Peloponnese has been one of the cradles of the Classical European civilization and an important contributor to the ancient European history. It has also been the subject of a controversy about the ancestry of its population. In a theory hotly debated by scholars for over 170 years, the German historian Jacob Philipp Fallmerayer proposed that the medieval Peloponneseans were totally extinguished by Slavic and Avar invaders and replaced by Slavic settlers during the 6th century CE. Here we use 2.5 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms to investigate the genetic structure of Peloponnesean populations in a sample of 241 individuals originating from all districts of the peninsula and to examine predictions of the theory of replacement of the medieval Peloponneseans by Slavs. We find considerable heterogeneity of Peloponnesean populations exemplified by genetically distinct subpopulations and by gene flow gradients within Peloponnese. By principal component analysis (PCA) and ADMIXTURE analysis the Peloponneseans are clearly distinguishable from the populations of the Slavic homeland and are very similar to Sicilians and Italians. Using a novel method of quantitative analysis of ADMIXTURE output we find that the Slavic ancestry of Peloponnesean subpopulations ranges from 0.2 to 14.4%. -

Early Mycenaean Arkadia: Space and Place(S) of an Inland and Mountainous Region

Early Mycenaean Arkadia: Space and Place(s) of an Inland and Mountainous Region Eleni Salavoura1 Abstract: The concept of space is an abstract and sometimes a conventional term, but places – where people dwell, (inter)act and gain experiences – contribute decisively to the formation of the main characteristics and the identity of its residents. Arkadia, in the heart of the Peloponnese, is a landlocked country with small valleys and basins surrounded by high mountains, which, according to the ancient literature, offered to its inhabitants a hard and laborious life. Its rough terrain made Arkadia always a less attractive area for archaeological investigation. However, due to its position in the centre of the Peloponnese, Arkadia is an inevitable passage for anyone moving along or across the peninsula. The long life of small and medium-sized agrarian communities undoubtedly owes more to their foundation at crossroads connecting the inland with the Peloponnesian coast, than to their potential for economic growth based on the resources of the land. However, sites such as Analipsis, on its east-southeastern borders, the cemetery at Palaiokastro and the ash altar on Mount Lykaion, both in the southwest part of Arkadia, indicate that the area had a Bronze Age past, and raise many new questions. In this paper, I discuss the role of Arkadia in early Mycenaean times based on settlement patterns and excavation data, and I investigate the relation of these inland communities with high-ranking central places. In other words, this is an attempt to set place(s) into space, supporting the idea that the central region of the Peloponnese was a separated, but not isolated part of it, comprising regions that are also diversified among themselves. -

The Helot Revolt of Sparta Greece

464 B.C. The Helot Revolt of Sparta Greece Sparta, at first, was only the Messenia and Laconia territories, and later the Spartans (previously known as the Dorians) came and took over those territories. Those places they conquered had other residents who were captured and used them as Spartan “slaves” (also known as Helots) for the growing nation. However, these Helots were not the property of anyone or under the control of a specific person. They worked for Sparta in general, and since the Dorians couldn’t do agriculture, they made the Helots do the work. The Dorians were “Barbarians,” note them taking over territories. Unlike the slaves that we know today, these ones were able to go wherever they want in Spartan territory and they could live normal lives like the Spartans.The Helots lived in houses together for a plot of land that they worked on. They were allowed families, to go away from their house and make cash for themselves. Occasionally, the Helots would be assigned to help out in the military. However, not all Helots were happy where they were at. Around 660 B.C., the Spartans attacked the Argives, who demolished the Spartans. The report of Sparta’s lost gave encouragement to the Helots who started a revolt against Sparta, which is now known as the Second Messenian War. The Spartans were fighting to gain back control, but they were outnumbered seven Helots to one Spartan. The details about this war were concealed, and very little information is known about what happened in the war. -

Coastal Petalidi of Messinia

Coastal Petalidi of Messinia Plan Days 3 A three days trip with beautiful beaches, hiking, magical castles and ancient cultures combined with accommodation in the traditional Stone Built Houses of Moorea Houses. By: Christina Koraki PLAN SUMMARY Day 1 1. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation 2. Ancient Messini Culture/Archaelogical sites 3. Archaeological Museum of Ancient Messene Culture/Museums 4. Pamisos Nature/Rivers 5. Archaeological Museum of Kalamata Culture/Museums 6. Tzanes Nature/Beaches 7. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation Day 2 1. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation 2. Pylos Castle (Niokastro) Culture/Castles 3. Voidokilia Nature/Beaches 4. Methoni Castle Culture/Castles 5. Polylimnio Nature/Waterfalls 6. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation Day 3 1. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation 2. Vrahakia Nature/Beaches 3. Koroni Castle Culture/Castles 4. Koroni Nature/Beaches WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 1 Day 1 1. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Απόσταση: Start - Accommodation Χρόνος: - GPS: N36.960132529625945, W21.927522284130873 Note: Arriving at Petalidi, you will find the characteristic beauty of the Mediterranean coastal village with olive and fig trees giving a special charm. 2. Ancient Messini Απόσταση: by car 38.3km Culture / Archaelogical sites Χρόνος: 46′ GPS: N37.17531525140723, W21.920112358789083 Note: How an inhabitant lived in Ancient Messini? Where did he walk? Which buildings was looking on when was coming out of his house? These one will feel when visiting the ancient Messina. This really is a feeling, not a mere visual impression. 3. Archaeological Museum of Ancient Location: Ancient Messene (Mavromati) Messene Culture / Museums Contact: Τ: (+30) 27240 51201, 51046 Απόσταση: by car 1.0km Χρόνος: 10′ GPS: N37.18152235244687, W21.917387528419567 4. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

16 506 Oversikt

Tel : +47 22413030 | Epost :[email protected]| Web :www.reisebazaar.no Karl Johans gt. 23, 0159 Oslo, Norway Highlights of Ancient Greece Turkode Destinasjoner Turen starter AGM Hellas Athens Turen destinasjon Reisen er levert av 9 dager Athens Fra : NOK 16 506 Oversikt Journey through thousands of years of Greece’s history. Reiserute Day 1 Start Athens. There are no included activities today so you are free to arrive in Athens at any time. The group flight usually arrives in Athens in the early afternoon. Accommodation: Arion Hotel or similarComfortable Hotel Day 2 Morning walking tour of Athens, including the Acropolis, the Museum of Acropolis and Plaka; afternoon free to explore Athens. This morning there is a walking tour of Athens, the historical capital of Europe, and the birthplace of democracy, dating back to the Neolithic Age. The archaeological sites of major interest that we will visit include the Acropolis and the Museum of Acropolis, also known as the city’s historical centre. This walk is actually a journey through history itself, where you will see classic ancient history, architectural evolution, and the city’s development until the 21st century (Classic period, Romaic period, Byzantine, Ottoman occupation, Neoclassic times, and 20th century).The afternoon is free for you to continue to explore Athens on your own, your leader will be able to suggest where to visit. Please note: During busy periods, the walking tour might take place in the afternoon when it is quieter and the morning will be free. Accommodation: Arion Hotel or similarComfortable Hotel Day 3 To Nafplio, visiting Ancient Corinth and Mycenae en route. -

Spartan Suspicions and the Massacre, Again1 Sospechas Espartanas Y La Masacre, De Nuevo

Spartan Suspicions and the Massacre, Again1 Sospechas espartanas y la masacre, de nuevo Annalisa Paradiso2 Università della Basilicata (Italia) Recibido: 27-02-17 Aprobado: 28-03-17 Abstract While narrating Brasidas’ expedition to Thrace and the Spartans’ decision to send 700 helots to accompany him as hoplites, Thucydides refers to another episode of helots’ enfranchisement, followed however by their massacre. The association of the timing of the two policies is indeed suspect, whereas it is possible that in the second case the slaughter may have been carried out in different chasms in Laconia, rather than in the so-called Kaiadas, after dividing the helots into groups. Key-words: Thucydides, Sparta, Massacre, Kaiadas. Resumen Mientras narra la expedición de Brásidas a Tracia y la decisión de los espartanos de enviarle 700 ilotas que le acompañaran como hoplitas, Tucídides refiere otro episodio de manumisión de ilotas, seguido empero de su masacre. La coincidencia de ambas medidas políticas es en efecto sospechosa, si tenemos en cuenta que en el segundo caso la matanza puede haberse llevado a cabo en desfiladeros diferentes de Laconia, y no en el llamado Kaiadas, tras dividir a los ilotas en grupos. Palabras-clave: Tucídides, Esparta, masacre, Kaiadas. 1 This article has been improved through information and comments supplied by Yanis Pikoulas, Dimitris Roubis, and James Roy. I am grateful to them and to Maria Serena Patriziano, physical anthropologist, who provided the volumetric calculations. 2 ([email protected]) She is Lecturer of Greek History at the Department of European and Mediterranean Cultures, Architecture, Environment and Cultural Heritage of the University of Basilicata (Matera, Italy). -

Notes and Inscriptions from South-Western Messenia Author(S): Marcus Niebuhr Tod Source: the Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol

Notes and Inscriptions from South-Western Messenia Author(s): Marcus Niebuhr Tod Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 25 (1905), pp. 32-55 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/624207 . Accessed: 14/06/2014 14:24 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.239.116.185 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 14:24:24 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions NOTES AND INSCRIPTIONS FROM SOUTH-WESTERN MESSENIA. I.-Introduction. THE following notes and inscriptions represent part of the results of a journey made in the spring of 1904, supplemented and revised on a second visit paid to the same district in the following November. One iuscription from Korone, a fragment of the 'Edictum Diocletiani,' I have already published (J.H.S. 1904, p. 195 foll.). I have attempted to state as briefly as possible the fresh topographical evidence collected on my tour, avoiding as far as possible any mere repetition of the descriptions and discussions of previous writers. -

Earthquake: Detailed Study of a Normal Fault, Evidences for East-West Extension in the Hellenic Arc H Lyon-Caen, R

The 1986 Kalamata (South Peloponnesus) Earthquake: Detailed Study of a Normal Fault, Evidences for East-West Extension in the Hellenic Arc H Lyon-Caen, R. Armijo, J Drakopoulos, J Baskoutass, N Delibassis, R. Gaulon, V Kouskouna, J Latoussakis, K. Makropoulos, P Papadimitriou, et al. To cite this version: H Lyon-Caen, R. Armijo, J Drakopoulos, J Baskoutass, N Delibassis, et al.. The 1986 Kalamata (South Peloponnesus) Earthquake: Detailed Study of a Normal Fault, Evidences for East-West Extension in the Hellenic Arc. Journal of Geophysical Research, American Geophysical Union, 1988, 93, pp.967 - 982. hal-01994159 HAL Id: hal-01994159 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01994159 Submitted on 25 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 93, NO. B12, PAGES 14,967-15,000, DECEMBER 10, 1988 The 1986Kalemate (South Peloponnesus) Earthquake' Detailed Study of a Normal Fault, Evidences for East-West Extension in the Hellenic Arc H. LYON-CAEN,1 R. ARMIJO,2 J. DRAKOPOULOS,3'4 J. BASKOUTASS,4 N. DELIBASSIS,3 R. GAULON,1 V. KOUSKOUNA,3 J. LATOUSSAKIS,4 K. MAKROPOULOS,3 P. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

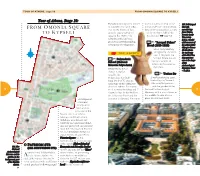

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Iconography of the Gorgons on Temple Decoration in Sicily and Western Greece

ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE By Katrina Marie Heller Submitted to the Faculty of The Archaeological Studies Program Department of Sociology and Archaeology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 2010 Copyright 2010 by Katrina Marie Heller All Rights Reserved ii ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE Katrina Marie Heller, B.S. University of Wisconsin - La Crosse, 2010 This paper provides a concise analysis of the Gorgon image as it has been featured on temples throughout the Greek world. The Gorgons, also known as Medusa and her two sisters, were common decorative motifs on temples beginning in the eighth century B.C. and reaching their peak of popularity in the sixth century B.C. Their image has been found to decorate various parts of the temple across Sicily, Southern Italy, Crete, and the Greek mainland. By analyzing the city in which the image was found, where on the temple the Gorgon was depicted, as well as stylistic variations, significant differences in these images were identified. While many of the Gorgon icons were used simply as decoration, others, such as those used as antefixes or in pediments may have been utilized as apotropaic devices to ward off evil. iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my family and friends for all of their encouragement throughout this project. A special thanks to my parents, Kathy and Gary Heller, who constantly support me in all I do. I need to thank Dr Jim Theler and Dr Christine Hippert for all of the assistance they have provided over the past year, not only for this project but also for their help and interest in my academic future. -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions.