A.C~ Cronıbie the History of Science Trom AUGUSTINE to GALILEO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Aquinas on the Separability of Accidents and Dietrich of Freiberg’S Critique

Thomas Aquinas on the Separability of Accidents and Dietrich of Freiberg’s Critique David Roderick McPike Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Philosophy Department of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © David Roderick McPike, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract The opening chapter briefly introduces the Catholic doctrine of the Eucharist and the history of its appropriation into the systematic rational discourse of philosophy, as culminating in Thomas Aquinas’ account of transubstantiation with its metaphysical elaboration of the separability of accidents from their subject (a substance), so as to exist (supernaturally) without a subject. Chapter Two expounds St. Thomas’ account of the separability of accidents from their subject. It shows that Thomas presents a consistent rational articulation of his position throughout his works on the subject. Chapter Three expounds Dietrich of Freiberg’s rejection of Thomas’ view, examining in detail his treatise De accidentibus, which is expressly dedicated to demonstrating the utter impossibility of separate accidents. Especially in light of Kurt Flasch’s influential analysis of this work, which praises Dietrich for his superior level of ‘methodological consciousness,’ this chapter aims to be painstaking in its exposition and to comprehensively present Dietrich’s own views just as we find them, before taking up the task of critically assessing Dietrich’s position. Chapter Four critically analyses the competing doctrinal positions expounded in the preceding two chapters. It analyses the various elements of Dietrich’s case against Thomas and attempts to pinpoint wherein Thomas and Dietrich agree and wherein they part ways. -

Renaissance Theories of Vision Edited by John Hendrix, University of Lincoln, UK and Rhode Island School of Design and Roger Williams University, USA, and Charles H

Renaissance Theories of Vision Edited by John Hendrix, University of Lincoln, UK and Rhode Island School of Design and Roger Williams University, USA, and Charles H. Carman, University at Buffalo, USA Visual Culture in Early Modernity December 2010 244 x 172 mm 258 pages Hardback 978-1-4094-0024-0 £65.00 Includes 18 b&w illustrations How are processes of vision, perception, and sensation conceived in the Renaissance? How are those conceptions made manifest in the arts? The essays in this volume address these and similar questions to establish important theoretical and philosophical bases for artistic production in the Renaissance and beyond. The essays also attend to the views of historically significant writers from the ancient classical period to the eighteenth century, including Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, St Augustine, Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), Ibn Sahl, Marsilio Ficino, Nicholas of Cusa, Leon Battista Alberti, Gian Paolo Lomazzo, Gregorio Comanini, John Davies, Rene Descartes, Samuel van Hoogstraten, and George Berkeley. Contributors carefully scrutinize and illustrate the effect of changing and evolving ideas of intellectual and physical vision on artistic practice in Florence, Rome, Venice, England, Austria, and the Netherlands. The artists whose work and practices are discussed include Fra Angelico, Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, Filippino Lippi, Giovanni Bellini, Raphael, Parmigianino, Titian, Bronzino, Johannes Gumpp and Rembrandt van Rijn. Taken together, the essays provide the reader with a fresh perspective on the intellectual confluence between art, science, philosophy, and literature across Renaissance Europe. Contents Introduction, John S. Hendrix and Charles H. Carman; Classical optics and the perspectivae traditions leading to the Renaissance, Nader El-Bizri; Meanings of perspective in the Renaissance: tensions and resolution, Charles H. -

Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 Pm Page 23

001_025 (Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 pm Page 23 ENTRIES BY THEME Apparatus, Equipment, Implements, Techniques Weights and measures Agriculture Windmills Alum Arms and armor Biography Artillery and fire arms Abelard, Peter Brewing Abraham bar Hiyya Bridges Abu Ma‘shar al Balkh (Albumasar) Canals Adelard of Bath Catapults and trebuchets Albert of Saxony Cathedral building Albertus Magnus Clepsydra Alderotti, Taddeo Clocks and timekeeping Alfonso X the Wise Coinage, Minting of Alfred of Sareschel Communication Andalusi, Sa‘id al- Eyeglasses Aquinas, Thomas Fishing Archimedes Food storage and preservation Arnau de Vilanova Gunpowder Bacon, Roger Harnessing Bartholomaeus Anglicus House building, housing Bartholomaeus of Bruges Instruments, agricultural Bartholomaeus of Salerno Instruments, medical Bartolomeo da Varignana Irrigation and drainage Battani, al- (Albategnius) Leather production Bede Military architecture Benzi, Ugo Navigation Bernard de Gordon Noria Bernard of Verdun Paints, pigments, dyes Bernard Silvester Paper Biruni, al- Pottery Boethius Printing Boethius of Dacia Roads Borgognoni, Teodorico Shipbuilding Bradwardine, Thomas Stirrup Bredon, Simon Stone masonry Burgundio of Pisa Transportation Buridan, John Water supply and sewerage Campanus de Novara Watermills Cecco d’Ascoli xxiii 001_025 (Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 pm Page 24 xxii ENTRIES BY THEME Chaucer, Geoffrey John of Saint-Amand Columbus, Christopher John of Saxony Constantine the African John of Seville Despars, Jacques Jordanus de Nemore Dioscorides Khayyam, al- Eriugena, -

REBIRTH, REFORM and RESILIENCE Universities in Transition 1300-1700

REBIRTH, REFORM AND RESILIENCE Universities in Transition 1300-1700 Edited by James M. Kittelson and Pamela J. Transue $25.00 REBIRTH, REFORM, AND RESILIENCE Universities in Transition, 1300-1700 Edited by James M. Kittelson and Pamela]. Transue In his Introduction to this collection of original essays, Professor Kittelson notes that the university is one of the few institutions that medieval Latin Christendom contributed directly to modern Western civilization. An export wherever else it is found, it is unique to Western culture. All cultures, to be sure, have had their intellec tuals—those men and women whose task it has been to learn, to know, and to teach. But only in Latin Christendom were scholars—the company of masters and students—found gathered together into the universitas whose entire purpose was to develop and disseminate knowledge in a continu ous and systematic fashion with little regard for the consequences of their activities. The studies in this volume treat the history of the universities from the late Middle Ages through the Reformation; that is, from the time of their secure founding, through the period in which they were posed the challenges of humanism and con fessionalism, but before the explosion of knowl edge that marked the emergence of modern science and the advent of the Enlightenment. The essays and their authors are: "University and Society on the Threshold of Modern Times: The German Connection," by Heiko A. Ober man; "The Importance of the Reformation for the Universities: Culture and Confessions in the Criti cal Years," by Lewis W. Spitz; "Science and the Medieval University," by Edward Grant; "The Role of English Thought in the Transformation of University Education in the Late Middle Ages," by William J. -

Some Milestones in History of Science About 10,000 Bce, Wolves Were Probably Domesticated

Some Milestones in History of Science About 10,000 bce, wolves were probably domesticated. By 9000 bce, sheep were probably domesticated in the Middle East. About 7000 bce, there was probably an hallucinagenic mushroom, or 'soma,' cult in the Tassili-n- Ajjer Plateau in the Sahara (McKenna 1992:98-137). By 7000 bce, wheat was domesticated in Mesopotamia. The intoxicating effect of leaven on cereal dough and of warm places on sweet fruits and honey was noticed before men could write. By 6500 bce, goats were domesticated. "These herd animals only gradually revealed their full utility-- sheep developing their woolly fleece over time during the Neolithic, and goats and cows awaiting the spread of lactose tolerance among adult humans and the invention of more digestible dairy products like yogurt and cheese" (O'Connell 2002:19). Between 6250 and 5400 bce at Çatal Hüyük, Turkey, maces, weapons used exclusively against human beings, were being assembled. Also, found were baked clay sling balls, likely a shepherd's weapon of choice (O'Connell 2002:25). About 5500 bce, there was a "sudden proliferation of walled communities" (O'Connell 2002:27). About 4800 bce, there is evidence of astronomical calendar stones on the Nabta plateau, near the Sudanese border in Egypt. A parade of six megaliths mark the position where Sirius, the bright 'Morning Star,' would have risen at the spring solstice. Nearby are other aligned megaliths and a stone circle, perhaps from somewhat later. About 4000 bce, horses were being ridden on the Eurasian steppe by the people of the Sredni Stog culture (Anthony et al. -

Book of Optics Jim Al-Khalili Revisits Ibn Al-Haytham’S Hugely Influential Study on Its Millennium

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT IN RETROSPECT Book of Optics Jim Al-Khalili revisits Ibn al-Haytham’s hugely influential study on its millennium. he greatest physicist of the medieval era vision and the associated physiology of the led a life as remarkable as his discover- eye and the psychology of perception; and ies were prodigious, spending a decade Books IV to VII, covering traditional physi- Tin prison and at one point possibly feigning cal optics. The work’s most celebrated contri- mental illness to get out of a tight spot. Abu bution to science is its explanation of vision. Ali al-Hassan ibn al-Haytham (Latinized to At that time, scholars’ understanding of Alhazen) was born in Basra, now in southern the phenomenon was a mess. The Greeks Iraq, in ad 965. His greatest and most famous had several theories. In the fifth century bc, work, the seven-volume Book of Optics (Kitab Empedocles had argued that a special light al-Manathir) hugely influenced thinking shone out of the eye until it hit an object, across disciplines from the theory of visual thereby making it visible. This became perception to the nature of perspective in known as the emission theory of vision. It medieval art, in both the East and the West, was ‘refined’ by Plato, who explained that for more than 600 years. Many later European you also need external light to see. Plato’s stu- scholars and fellow polymaths, from Robert dent Aristotle suggested that rather than the CAMBRIDGE OF TRINITY COLLEGE, AND FELLOWS THE MASTER Grosseteste and Leonardo da Vinci to Galileo eye emitting light, objects would ‘perturb’ Galilei, René Descartes, Johannes Kepler and the air between them and the eye, triggering Isaac Newton, were in his debt. -

Response to Guy Bedouille's Lecture

Response to Velma Richmond's Lecture St. Mary Magdalen Church by Michael J. Dodds, OP 7/20/2019 I'm grateful to Velma for her very illuminating and informative lecture. Since Velma dealt especially with literature and art, I thought I might throw in a bit of science, just to round things out. As Velma mentioned, St. Thomas Aquinas calls Mary Magdalen, "the apostle to the apostles." He does is in his Commentary on the Gospel of John, where he has a couple of other titles for her as well. He says: Notice the three privileges given to Mary Magdalene. First, she had the privilege of being a prophet because she was worthy enough to see the angels, for a prophet is an intermediary between angels and the people. Secondly, she had the dignity or rank of an angel insofar as she looked upon Christ, on whom the angels desire to look. Thirdly, she had the office of an apostle; indeed, she was the apostle to the apostles (apostolorum apostola) insofar as it was her task to announce our Lord's resurrection to the disciples.1 An apocryphal sermon on St. Mary Magdalen, attributed to Aquinas, uses the image of a rainbow to depict her meeting with the risen Christ. As the rays of the sun meet the water of a cloud to produce the colors of the rainbow, so the light of the risen Christ meets Mary Magdalen, clouded in the water of her tears, to produce the characteristic colors associated with her iconography—the blue of humility and the red of faith. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13021-0 — the Rise of Early Modern Science 3Rd Edition Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13021-0 — The Rise of Early Modern Science 3rd Edition Index More Information Index ‘Abduh, Muhammad, 139, 170 Averröes (Ibn Rushd), 66, 92–4, 98n, 137 ‘Ali, 78 Avicenna, see Ibn Sina Abelard, Peter, 88, 103, 106, 174, 245, 301 Awrangzeb, 127 Abu Bakr, 78 al-Azhar, 167 Abu Bishr Matta, 146–7 Accademy dei Linci, 269 Bacon, Francis, 44 Adelard of Bath, 107 Bacon, Roger, 258, 295 advocates, 116–17, 137 Baghdad, 143, 145, 152 al-Afghani, Jamal al-Din, 170 al-Baghadadi, ‘Abd al-Latif, 151 air, weight of, 6 Ibn Bajja, 65 Alfonsine tables, 68 Balazs, Etienne, 234, 246 Alford, William, 219n Bardeen, John, 331 algebra, 176, 261, 263, 295 Basalla, George, 28n Allee, Mark, 227n Basel, 297 Allen, Robert C, 330n al-Battani, 62, 64 Almagest, 63, 64, 71, 176, 177, 264, 271, 295, 303 Bayer, Johann, 281 anatomy, 156–61, 297, 322 Bekar, Clifford, 332 Chinese study of, 242–5, 255 Ben-David, 7, 17, 19–25, 51 Anselm of Canterbury, 174 Bentley, R, 318n Apollonius of Perga, 97 Berkey, Jonathan, 141n, 144n Aquinas, 88, 245 Berman, Harold J., x, 11, 121–2, 132, 233 Arab Spring, xi, 331 Bernard of Chartres, 174 Arab, defined, 55n Bible, 94, 107, 108, 112, 119, 141, 174, 303, 306 Arabic grammar, 83 biology, 35 Arabic science, 53ff al-Bitruji, 64 Arabic-Islamic civilization, 36, 76ff Blue, Gregory, 261 Arabic-Islamic world, 294 Bodde, Derk, 14n, 203, 205, 209n, 214n, 220n, Archimedes, 21, 97 222n, 249, 261 Aristarchus, 97 Bohannan, Paul, 220n, 223n Aristotle, 97f, 102, 104, 166, 176, 179, 180, 181, 182, Bologna, 173, 185, 187, 191, -

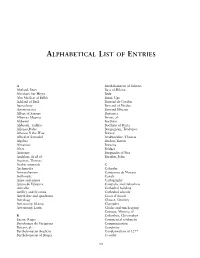

A-Z Entries List

001_025 (Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 pm Page 19 ALPHABETICAL LIST OF ENTRIES A Bartholomaeus of Salerno Abelard, Peter Bayt al-Hikma Abraham bar Hiyya Bede Abu Ma’shar al Balkh Benzi, Ugo Adelard of Bath Bernard de Gordon Agriculture Bernard of Verdun Agrimensores Bernard Silvester Albert of Saxony Bestiaries Albertus Magnus Biruni, al- Alchemy Boethius Alderotti, Taddeo Boethius of Dacia Alfonso,Pedro Borgognoni, Teodorico Alfonso X the Wise Botany Alfred of Sareschel Bradwardine, Thomas Algebra Bredon, Simon Almanacs Brewing Alum Bridges Anatomy Burgundio of Pisa Andalusi, Sa‘id al- Buridan, John Aquinas, Thomas Arabic numerals C Archimedes Calendar Aristotelianism Campanus de Novara Arithmetic Canals Arms and armor Cartography Arnau de Vilanova Catapults and trebuchets Articella Cathedral building Artilley and firearms Cathedral schools Astrolabes and quadrants Cecco d’Ascoli Astrology Chauce, Geoffrey Astronomy, Islamic Clepsydra Astronomy, Latin Clocks and timekeeping Coinage, Minting of B Columbus, Christopher Bacon, Roger Commercial arithmetic Bartolomeo da Varignana Communication Battani, al- Computus Bartholomaeus Anglicus Condemnation of 1277 Bartholomaeus of Bruges Consilia xix 001_025 (Roman) Prelims 22/6/05 2:15 pm Page 20 xx ALPHABETICAL LIST OF ENTRIES Constantine the African I Cosmology Ibn al-Haytham Ibn al-Saffar D Ibn al-Samh Despars, Jacques Ibn al-Zarqalluh Dioscorides Ibn Buklarish Duns Scotus, Johannes Ibn Ezra, Abraham Ibn Gabirol E Ibn Majid, Ahmad Elements and qualities Ibn Rushd Encyclopaedias Ibn Sina Eriugena, -

Bonum Non Est in Deo: on the Indistinction of the One and the Exclusion of the Good in Meister Eckhart

BONUM NON EST IN DEO: ON THE INDISTINCTION OF THE ONE AND THE EXCLUSION OF THE GOOD IN MEISTER ECKHART by Evan King Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2012 © Copyright by Evan King, 2012 DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS The undersigned hereby certify that they have read and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance a thesis entitled “BONUM NON EST IN DEO: ON THE INDISTINCTION OF THE ONE AND THE EXCLUSION OF THE GOOD IN MEISTER ECKHART” by Evan King in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Dated: 24 August 2012 Supervisor: _________________________________ Readers: _________________________________ _________________________________ ii DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY DATE: 24 August 2012 AUTHOR: Evan King TITLE: BONUM NON EST IN DEO: ON THE INDISTINCTION OF THE ONE AND THE EXCLUSION OF THE GOOD IN MEISTER ECKHART DEPARTMENT OR SCHOOL: Department of Classics DEGREE: MA CONVOCATION: October YEAR: 2012 Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non-commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions. I understand that my thesis will be electronically available to the public. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission. The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material appearing in the thesis (other than the brief excerpts requiring only proper acknowledgement in scholarly writing), and that all such use is clearly acknowledged. -

II the Middle Ages

History of Theology II The Middle Ages History of Theology II The Middle Ages Giulio D’Onofrio Translated by Matthew J. O’Connell A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by David Manahan, OSB. This book was originally published in Italian under the title Storia della teologia II, eta’ medievale © Edizioni Piemme Spa (Via del Carmine 5, 15033 Casale Monferrato [AL], Italy). All rights reserved. © 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, micro fiche, mechani- cal recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permis- sion of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, P.O. Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 978-0-8146-5915-1 (vol. I) ISBN 978-0-8146-5916-8 (vol. II) ISBN 978-0-8146-5917-5 (vol. III) 12345678 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Storia della teologia. English. History of theology / edited by Angelo Di Berardino and Basil Studer ; translated by Matthew J. O’Connell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: I. The patristic period. ISBN 0-8146-5915-2 1. Theology, Doctrinal—History. 2. Catholic Church—Doctrines—History. I. Di Berardino, Angelo. II. Studer, Basil, 1925– III. Title. BT21.2.S7613 1996 230'.09—DC20 96-42160 CIP Contents Preface xiii Introduction: The Principles of Medieval Theology 1 1. -

Berthold of Moosburg and the Divine Science of the Platonists

chapter 3 Praeambulum libri The habit of our divinising beyond- wisdom exceeds every other habit, not only of the sciences, but even the habit of intellect that is wisdom, through which Aristotle receives the principles of his first philosophy, which is merely of beings.1 ∵ Berthold has moved from the consensus of authorities in the Prologus to the focalisation of ancient wisdom on Proclus and his works in the Expositio tituli. The third and final preface to the Expositio is a Praeambulum to the first thirteen Propositions, and establishes the rational and scientific validity of the knowl- edge transmitted in the Elementatio theologica. In sequence, the three prefaces thus display roughly the same pattern found in each of Berthold’s commen- taries (suppositum, propositum, commentum), which move from the general and authoritative background to the textual specificity of the Elementatio, and finally to demonstration alone. In Berthold’s view, Proclus’ first thirteen propositions formed a coherent group, which established the existence of the One and the Good, demon- strated that the two names refer to the same first principle, and showed that everything that is one or is good derives from that principle. The Praeambulum aimed to account for the two “complex principles” or propositions that Proclus assumed in these arguments. Since these propositions are so fundamental for the remainder of the Elementatio, these two principles can be regarded as “the foundations” of Proclus’ philosophy. According to Berthold, Proposition 1 (Omnis multitudo etc.) assumed “that there is multitude” (multitudinem esse) and moved from the many to the One, while Proposition 7 (Omne productivum etc.) presupposed that “the productive exists” (productivum esse) and estab- lished the existence of the Good.