28 Architecture and Public Space: Lessons from Sao Paulo Zeuler Lima

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gawc Link Classification FINAL.Xlsx

High Barcelona Beijing Sufficiency Abu Dhabi Singapore sufficiency Boston Sao Paulo Barcelona Moscow Istanbul Toronto Barcelona Tokyo Kuala Lumpur Los Angeles Beijing Taiyuan Lisbon Madrid Buenos Aires Taipei Melbourne Sao Paulo Cairo Paris Moscow San Francisco Calgary Hong Kong Nairobi New York Doha Sydney Santiago Tokyo Dublin Zurich Tokyo Vienna Frankfurt Lisbon Amsterdam Jakarta Guangzhou Milan Dallas Los Angeles Hanoi Singapore Denver New York Houston Moscow Dubai Prague Manila Moscow Hong Kong Vancouver Manila Mumbai Lisbon Milan Bangalore Tokyo Manila Tokyo Bangkok Istanbul Melbourne Mexico City Barcelona Buenos Aires Delhi Toronto Boston Mexico City Riyadh Tokyo Boston Munich Stockholm Tokyo Buenos Aires Lisbon Beijing Nanjing Frankfurt Guangzhou Beijing Santiago Kuala Lumpur Vienna Buenos Aires Toronto Lisbon Warsaw Dubai Houston London Port Louis Dubai Lisbon Madrid Prague Hong Kong Perth Manila Toronto Madrid Taipei Montreal Sao Paulo Montreal Tokyo Montreal Zurich Moscow Delhi New York Tunis Bangkok Frankfurt Rome Sao Paulo Bangkok Mumbai Santiago Zurich Barcelona Dubai Bangkok Delhi Beijing Qingdao Bangkok Warsaw Brussels Washington (DC) Cairo Sydney Dubai Guangzhou Chicago Prague Dubai Hamburg Dallas Dubai Dubai Montreal Frankfurt Rome Dublin Milan Istanbul Melbourne Johannesburg Mexico City Kuala Lumpur San Francisco Johannesburg Sao Paulo Luxembourg Madrid Karachi New York Mexico City Prague Kuwait City London Bangkok Guangzhou London Seattle Beijing Lima Luxembourg Shanghai Beijing Vancouver Madrid Melbourne Buenos Aires -

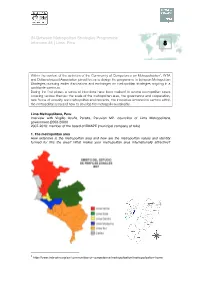

IN-Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme Interview #8 | Lima, Peru 8

IN-Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme Interview #8 | Lima, Peru 8 Within the context of the activities of the Community of Competence on Metropolisation1, INTA and Deltametropool Association joined forces to design the programme In-between Metropolitan Strategies pursuing earlier discussions and exchanges on metropolitan strategies ongoing in a worldwide spectrum. During the first phase, a series of interviews have been realised to several metropolitan cases covering various themes: the scale of the metropolitan area, the governance and cooperation, new forms of urbanity and metropolitan environments, the innovative economical sectors within the metropolitan area and how to develop the metropolis sustainably. Lima Metropolitana, Peru Interview with Virgilio Acuña Peralta, Peruvian MP, councillor of Lima Metropolitana government (2003-2006) 2007-2010: member of the board of EMAPE (municipal company of tolls) 1.! The metropolitan area How extensive is the metropolitan area and how are the metropolitan values and identity formed for this the area? What makes your metropolitan area internationally attractive? 1 http://www.inta-aivn.org/en/communities-of-competence/metropolisation/metropolisation-home In Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme – Interview 7 Lima Metropolitana counts 9 millions inhabitants (including the Province of Callao) and 42 districts. The administrative region of Lima Metropolitana (excluding Callao) has a total surface of 2800 km2. The metropolitan area has an extension of 150km North-South and 60Km on the West (sea coast) - East (toward the Andes) direction. The development of the city with urban sprawl goes south, towards the seaside resorts, outside of the administrative limits of Lima Metropolitana (Province of Cañete, City of Ica) and to the Northern beach areas. -

Spanish Impact on Peru (1520 - 1824)

Spanish Impact on Peru (1520 - 1824) San Francisco Cathedral (Lima) Michelle Selvans Setting the stage in Peru • Vast Incan empire • 1520 - 30: epidemics halved population (reduced population by 80% in 1500s) • Incan emperor and heir died of measles • 5-year civil war Setting the stage in Spain • Iberian peninsula recently united after 700 years of fighting • Moors and Jews expelled • Religious zeal a driving social force • Highly developed military infrastructure 1532 - 1548, Spanish takeover of Incan empire • Lima established • Civil war between ruling Spaniards • 500 positions of governance given to Spaniards, as encomiendas 1532 - 1548, Spanish takeover of Incan empire • Silver mining began, with forced labor • Taki Onqoy resistance (‘dancing sickness’) • Spaniards pushed linguistic unification (Quechua) 1550 - 1650, shift to extraction of mineral wealth • Silver and mercury mines • Reducciones used to force conversion to Christianity, control labor • Monetary economy, requiring labor from ‘free wage’ workers 1550 - 1650, shift to extraction of mineral wealth • Haciendas more common: Spanish and Creole owned land, worked by Andean people • Remnants of subsistence-based indigenous communities • Corregidores and curacas as go- betweens Patron saints established • Arequipa, 1600: Ubinas volcano erupted, therefor St. Gerano • Arequipa, 1687: earthquake, so St. Martha • Cusco, 1650: earthquake, crucifix survived, so El Senor de los Temblores • Lima, 1651: earthquake, crucifixion scene survived, so El Senor de los Milagros By 1700s, shift -

FGV Direito Rio in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

FGV Direito Rio in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil FGV Direito Rio is one of the most well respected education institutions in one of the most exciting international cities in the world. There are more than 3,000 undergraduate students and almost 2,000 graduate and master’s students enrolled. During the 2019-20 academic year, no U of M Law students participated in the semester exchange. Summary of Course Offerings http://direitorio.fgv.br/graduacao/gradecurricular Semester Dates Fall semester: August through December 2020 Spring semester: February to July 2021 Language of instruction Portuguese; four to six courses are offered in English each semester Courses/Credits/Grades Up to 15 credits may be transferred per semester abroad Each class period is 100 minutes; each course has either 30 or 60 “course hours” Grading is from 0 (minimum) to 10 (maximum) with a passing grade being 7 2 ECTS Credits = 1 Minnesota Credit Registration Registration is done by the International Office prior to the student’s arrival. Participate in our Law School’s lottery for the term you will be away. Register for 12-15 credits. Before leaving for your semester abroad, contact the Law School registrar at [email protected] to convert your credits to Off-campus Legal Studies. Housing FGV Direito Rio does not have on-campus housing for international students. They will provide assistance once students arrive in locating and obtaining off-campus accommodations. Financial Aid and Tuition Payment Financial aid will remain in effect for the semester you are abroad. Please make arrangements to have the balance (after tuition is deducted) sent to you if disbursement occurs after you have departed the U.S. -

Buenos Aires to Lima By

FH {SR--27 The Bolivar Hotel Lima, Peru August 31, 1942 Dear hr. <oer s It is surprising how simple and relatively unexciting it seems to fly. Saturday, August 22, I climbed aboard a seven-ton, two-motored anagra plane and took off for the first time in my.life on the first lap of a 6,000 mile air journey--Buenos Aires to iiami. We were off and away without a bump. In a few minutes we were roaring high above the pampa. There is no reason to get poetic about a bird's eye view of the rGentine plains. For two and a half hours, at seven thousand feet, we moved over the flat gra. in belt. I amused myself by looking at the edge of the ing and watching one field after another come into view. That way one 5or the feeling of mo- tion.. any of the fields, I knew, were as large as five hundred or a thousand acres. One could count the chacras below. Every primitive bin or two meant a chacra. One could look right down upon th yel'low ,aize in thcorntrojes, uncovered and unpro- tected from the elements. Estancias were umistakable too, for stately groves of trees numbered them. Trees stood out best of all. In two hours flyin time the .green of the green fields bec-ame lighter, ore delicate, and I kno: that C6rdoba could not be very far away. Surely enoush, 6rdoba came into view, restin in a natural de- pression at the foot of the sierras and at the edge of the pampa. -

Paulonascimentoverano.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO Escola de Comunicações e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação PAULO NASCIMENTO VERANO POR UMA POLÍTICA CULTURAL QUE DIALOGUE COM A CIDADE O caso do encontro entre o MASP e o graffiti (2008-2011) São Paulo 2013 PAULO NASCIMENTO VERANO POR UMA POLÍTICA CULTURAL QUE DIALOGUE COM A CIDADE O caso do encontro entre o MASP e o graffiti (2008-2011) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, como requisito para obtenção do título de mestre em Ciência da Informação. Orientadora: Profª Drª Lúcia Maciel Barbosa de Oliveira Área de concentração: Informação e Cultura São Paulo 2013 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa desde que citada a fonte. PAULO NASCIMENTO VERANO POR UMA POLÍTICA CULTURAL QUE DIALOGUE COM A CIDADE O caso do encontro entre o MASP e o graffiti (2008-2011) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, como requisito para obtenção do título de mestre em Ciência da Informação. BANCA EXAMINADORA _____________________________________________________ a a Prof Dr Lúcia Maciel Barbosa de Oliveira (orientadora) Universidade de São Paulo _____________________________________________________ Universidade de São Paulo _____________________________________________________ Universidade de São Paulo CLARICE, CLARIDADE, CLARICIDADE. AGRADECIMENTOS Sou profundamente grato à Profa Dra Lúcia Maciel Barbosa de Oliveira pela oportunidade dada para a realização deste estudo. Sua orientação sempre presente e amiga, o diálogo aberto, as aulas ministradas, as indicações bibliográficas, a leitura atenta e exigente durante todas as fases desta dissertação, dos esboços iniciais à versão final. -

7. Another Museum (Display and Desire)

7. Another Museum (Display and Desire) The search for the real, in particular for real relations, and specifically the search for real relations between objects and people, takes on the form of utopia. Whether it be works of art (objects that are primarily non-relational), or products of the disenfranchised (objects of desperate survival), or ill-begotten treasures (objects collected in order to make the past present to the undeserving, taking away from others the possibility to figure the future), author Roger M Buergel, interpreting the displays of architect Lina Bo Bardi in the light of migration, and critic Pablo Lafuente, reading a work by artist Lukas Duwenhögger, demonstrate that things will, given the right circumstances, elicit subjectivity in spectatorship. agency, ambivalence, analysis: approaching the museum with migration in mind — 177 The Migration of a Few Things We Call − But Don’t Need to Call − Artworks → roger m buergel → i In 1946, 32-year-old Italian architect Lina Bo Bardi migrated to Brazil. She was accompanying her husband, Pietro Maria Bardi, who was a self- taught intellectual, gallerist and impresario of Italy’s architectural avant garde during Mussolini’s reign. Bardi had been entrusted by Assis de Chateaubriand, a Brazilian media tycoon and politician, with creating an art institution of international standing in São Paulo. Te São Paulo Art Museum (MASP) had yet to fnd an appropriate building to house its magnifcent collection of sculptures and paintings by artists ranging from Raphael to Manet. Te recent acquisitions were chosen by Bardi himself on an extended shopping spree funded by Assis Chateaubriand, who had taken out a loan from Chase Manhattan Bank in an impoverished, chaotic post-war Europe. -

El Ermitaño and Pampa De Cueva As Case Studies for a Regional Urbanization Strategy

Article Place-Making through the Creation of Common Spaces in Lima’s Self-Built Settlements: El Ermitaño and Pampa de Cueva as Case Studies for a Regional Urbanization Strategy Samar Almaaroufi 1, Kathrin Golda-Pongratz 1,2,* , Franco Jauregui-Fung 1 , Sara Pereira 1, Natalia Pulido-Castro 1 and Jeffrey Kenworthy 1,3,* 1 Department of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geomatics, Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences, 60318 Frankfurt, Germany; samarmaaroufi@gmail.com (S.A.); [email protected] (F.J.-F.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (N.P.-C.) 2 UIC School of Architecture, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, 08017 Barcelona, Spain 3 Curtin University Sustainability Policy Institute, Curtin University, Bentley 6102, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.G.-P.); jeff[email protected] (J.K.) Received: 30 October 2019; Accepted: 2 December 2019; Published: 10 December 2019 Abstract: Lima has become the first Peruvian megacity with more than 10 million people, resulting from the migration waves from the countryside throughout the 20th century, which have also contributed to the diverse ethnic background of today’s city. The paper analyzes two neighborhoods located in the inter-district area of Northern Lima: Pampa de Cueva and El Ermitaño as paradigmatic cases of the city’s expansion through non-formal settlements during the 1960s. They represent a relevant case study because of their complex urbanization process, the presence of pre-Hispanic heritage, their location in vulnerable hillside areas in the fringe with a protected natural landscape, and their potential for sustainable local economic development. The article traces back the consolidation process of these self-built neighborhoods or barriadas within the context of Northern Lima as a new centrality for the metropolitan area. -

December 2017

Immigrant Visa Issuances By Post December 2017 (FY 2018) Post Visa Class Issuances Abidjan CR1 5 Abidjan DV1 9 Abidjan DV2 3 Abidjan DV3 2 Abidjan F11 1 Abidjan F12 1 Abidjan F21 1 Abidjan F22 2 Abidjan F23 1 Abidjan F41 1 Abidjan F42 1 Abidjan F43 2 Abidjan FX1 3 Abidjan FX2 1 Abidjan IR2 6 Abidjan IR5 5 Abu Dhabi CR1 6 Abu Dhabi CR2 3 Abu Dhabi DV1 12 Abu Dhabi DV2 4 Abu Dhabi DV3 5 Abu Dhabi E11 1 Abu Dhabi E14 1 Abu Dhabi E15 1 Abu Dhabi E21 3 Abu Dhabi E31 10 Abu Dhabi E34 7 Abu Dhabi E35 7 Abu Dhabi F11 1 Abu Dhabi F21 2 Abu Dhabi F24 1 Abu Dhabi F33 5 Abu Dhabi F41 6 Abu Dhabi F42 4 Abu Dhabi F43 5 Abu Dhabi FX1 3 Abu Dhabi I51 15 Abu Dhabi I52 13 Abu Dhabi I53 23 Abu Dhabi IR1 4 Abu Dhabi IR2 4 Abu Dhabi IR5 7 Page 1 of 57 Immigrant Visa Issuances By Post December 2017 (FY 2018) Post Visa Class Issuances Accra CR1 45 Accra CR2 1 Accra DV1 24 Accra DV2 9 Accra DV3 14 Accra E31 1 Accra E34 1 Accra F11 19 Accra F12 9 Accra F21 22 Accra F22 20 Accra F23 3 Accra F24 2 Accra F31 6 Accra F32 6 Accra F33 10 Accra F41 11 Accra F42 7 Accra F43 7 Accra FX1 10 Accra FX2 15 Accra FX3 9 Accra IB3 1 Accra IR1 76 Accra IR2 101 Accra IR3 4 Accra IR5 79 Addis Ababa CR1 52 Addis Ababa DV1 109 Addis Ababa DV2 23 Addis Ababa DV3 24 Addis Ababa E11 2 Addis Ababa E14 2 Addis Ababa E15 4 Addis Ababa F11 10 Addis Ababa F12 1 Addis Ababa F21 27 Addis Ababa F22 25 Addis Ababa F24 10 Addis Ababa F25 1 Addis Ababa F41 3 Addis Ababa F42 2 Page 2 of 57 Immigrant Visa Issuances By Post December 2017 (FY 2018) Post Visa Class Issuances Addis Ababa F43 5 Addis -

Global Rescue Will Evacuate You to Your Home Hospital of Choice

Mumbai. Qogir. Shanghai. Karachi. Istanbul. Delhi. São Paulo. Moscow. Medical Evacuation. Seoul. Beijing. Mount Everest. Mexico City. Tokyo. Ja- karta. New York City. Lagos. Kinshasa. Nepal. Tehran. London. Manaslu. Security Evacuation. Lima. Bogotá. Hong Kong. Bangkok . Makalu. Cairo. Dhaka. Ho Chi Minh City. Annapurna. Rio de Janeiro. Tianjin. Chongqing. Baghdad. Lhotse. Bangalore.Kolkata. Yangon. Santiago. Pakistan. Singapore. Guangzhou. Nanga Parbat. Saint Petersburg. Wuhan. Chennai. Medical Evacuation. Riyadh. Alexandria. Surat. Hyderabad. Shenyang. Ahmedabad. Ankara. Field Rescue. Cho Oyu. Johannesburg. Los Angeles. Kangchenjunga. Abidjan. Yokohama. Busan. Cape Town. Durban. Berlin. Pune. Pyongyang. Madrid. Kanpur. Jaipur. Field Rescue. Buenos Aires. Dhaulagiri. Nairobi. Jeddah. Mumbai. Qogir. Shanghai. Security Evacuation. Karachi. Istanbul. Delhi. São Paulo. Moscow. Seoul. Beijing. Mount Everest. Mexico City. Tokyo. Jakarta. New York City. Lagos. Kinshasa. Nepal. Tehran. London. Manaslu. Lima. Bogotá. Hong Kong. Bangkok Makalu. Cairo. Dhaka. Ho Chi Minh City. Annapurna. Rio de Janeiro. Tianjin. Chongqing. Baghdad. Lhotse. Bangalore. Field Rescue. Kolkata. Yangon. Santiago. Pakistan. Singapore. Guangzhou. Nanga Parbat. Security Evacuation. Saint Petersburg. Wuhan. Medical Evacuation. Chennai. Riyadh. Alexandria. Surat. Hyderabad. Shenyang. Ahmedabad. Ankara. Cho Oyu. Johannesburg. Los Angeles. Kangchenjunga. Abidjan. Yokohama. Busan. Cape Town. Durban. Berlin. Pune. Pyongyang. Madrid. Kanpur. Jaipur. Buenos Aires. Dhaulagiri. Nairobi.Global Jeddah. Mumbai. Qogir. Shanghai. Rescue Karachi. Istanbul. Delhi. São Paulo. Moscow. Medical Evacuation. Seoul. Beijing. Mount Everest. Mexico City. Tokyo. Jakarta. New York City. Lagos. Kinshasa. Nepal. Tehran. London. Manaslu. Security Evacuation. Lima. Bogotá. Hong CriticalKong. Bangkok . ServicesMakalu. Cairo. Dhaka.Provided Ho Chi Minh to City. Stratfor Annapurna. Rio deEnterprises, Janeiro. Tianjin. Chongqing. LLC Baghdad. Lhotse. Bangalore.Kolkata. Yangon. Santiago. Pakistan. Singapore. Guangzhou. -

MAM Leva Obras De Seu Acervo Para As Ruas Da Cidade De São Paulo Em Painéis Urbanos E Projeções

MAM leva obras de seu acervo para as ruas da cidade de São Paulo em painéis urbanos e projeções Ação propõe expandir as fronteiras do Museu para além do Parque Ibirapuera, para toda a cidade, e busca atingir públicos diversos. Obras de artistas emblemáticos da arte brasileira, de Tarsila do Amaral a Regina Silveira, serão espalhadas pela capital paulista Incentivar e difundir a arte moderna e contemporânea brasileira, e torná-la acessível ao maior número possível de pessoas. Este é um dos pilares que regem o Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo e é também o cerne da ação inédita que a instituição promove nas ruas da cidade. O MAM expande seu espaço físico e, até 31 de agosto, apresenta obras de seu acervo em painéis de pontos de ônibus e projeções de escala monumental em edifícios do centro de São Paulo. A ação MAM na Cidade reforça a missão do Museu em democratizar o acesso à arte e surge, também, como resposta às novas dinâmicas sociais impostas pela pandemia. “A democratização à arte faz parte da essência do MAM, e é uma missão que desenvolvemos por meio de programas expositivos e iniciativas diversas, desde iniciativas pioneiras do Educativo que dialogam com o público diverso dentro e fora do Parque Ibirapuera, até ações digitais que ampliam o acesso ao acervo, trazem mostras online e conteúdo cultural. Com o MAM na Cidade, queremos promover uma nova forma de experienciar o Museu. É um presente que oferecemos à São Paulo”, diz Mariana Guarini Berenguer, presidente do MAM São Paulo. Ao longo de duas semanas, MAM na Cidade apresentará imagens de obras de 16 artistas brasileiros espalhadas pela capital paulista em 140 painéis em pontos de ônibus. -

The Lima-‐Paris Ac on Agenda (LPAA)

The Lima-Paris Acon Agenda (LPAA) Octubre 2015 LPAA – Background • UN Secretary-General’s Climate Summit (New York, September 2014) • Decision 1/CP.20 ‘Lima Call for Climate Acon’: “The Conference of Pares […] encourages the Execuve Secretary and the President of the Conference of the Pares to convene an annual high level event on enhancing implementaon of climate acon”. • Workstream 2 discussions and TEM’s process. LPAA – Raonale • Multude of actors are already engaged in climate acon, in different contexts and at different scales. • They need support for recognion, scaling up and to assess their acRon and related impacts. Ø Lima-Paris Acon Agenda (LPAA) LPAA – Objecves • Constute a broad plaZorm of selected mul sectoral cooperave iniaves, with the view to: - Showcasing progress made under the most promising iniaves and supporng their extension and replicaon - Encouraging new substanal commitments from new iniaves and actors, in all sectors - Promong cross-sectoral mul-stakeholder collaboraon - Highlighng linkages with SDGs - Building polical momentum ad bringing ‘the real world’ in climate negoaons (CoP21 decision?) - Ensuring the connuity and strenghtening of the Acon Agenda beyond Paris (SDGs implementaon etc.) Criteria for inclusion in the LPAA (1/2) • Ambious: short and long term quanfiable targets – transformave acons guided by a 2°C goal pathway. • Science based: Address a concrete impact of climate change. Transformave acons should apply new technologies, knowledge, communicaon strategy and/ or financial schemes that move a large group, industry, city or country towards a low carbon and more resilient future. • For cooperave internaonal iniaves: Mul-stakeholder approach – Inclusiveness – Balance regional representaon. Criteria for inclusion in the LPAA (2/2) • Capacity to deliver.