Public Health in Lima, Peru, 1535

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Poblacion En Situacion De Pobreza Organizada En Comedores Populares De Pampas De San Juan". Lima-Peru 1989-1991 Autora

CENTRO LATINOAMERICANO DE DEMOGRAFI PROGRAMA GLOBAL DE POBLACION Y DESARROLLO CURSO DE POSTGRADO EN POBLACION Y DESARROLLO SANTIAGO, CHILE, 199;;; LA POBLACION EN SITUACION DE POBREZA ORGANIZADA EN COMEDORES POPULARES DE PAMPAS DE SAN JUAN". LIMA-PERU 1989-1991 AUTORA: NANCY E. > ^ R C O N GUTIERREZ ASESOR: DR. HUGO CORVALAN SANTIAGO DE CHILE, 1992. C: L A D í -- SI C>Q T-'-í'I DOCPAL o o C iJ M C : T A C 1 o N S O B R E PO': SiOí4 EN i ATIWA A mi hija con amor y a mi padre, dirigente de toda la vida. INDICE INTRODUCCION CAPITULO I: MARCO CONTEXTUAL 1.1 El estado; crisis económica, política, social y su incidencia en la población peruana en los últimos 10 años. 1.2 Las migraciones, desborde de las ciudades: el caso de Lima Metropolitana. 1.3 Pobreza; población de Lima metropolitana en situación de pobreza. 1.4 Las organizaciones populares; los comedores como estrategias de vida de la población de Lima Metropolitana. CAPITULO II: METODOLOGIA CAPITULO III: La población del cono sur de Lima: El caso de las familias organizadas en comedores populares de Pampas de San Juan. 3.1 Ubicación y situación general de la zona de Pampas de San Juan. 3.2 Dinámica de la población .Población total y tasa de crecimiento .Composición de la población según edad y sexo .Fecundidad .Mortalidad .Migración 3.3 Situación económica 3.4 Alimentación - consumo 3.5 Educación 3.6 Salud 3.7 Vivienda 3.8 Aspecto político organizativo CAPITULO IV: ALGUNAS LINEAMIENTOS DE PROPUESTA DE TRABAJO CON ESTE GRUPO DE POBLACION. -

Gawc Link Classification FINAL.Xlsx

High Barcelona Beijing Sufficiency Abu Dhabi Singapore sufficiency Boston Sao Paulo Barcelona Moscow Istanbul Toronto Barcelona Tokyo Kuala Lumpur Los Angeles Beijing Taiyuan Lisbon Madrid Buenos Aires Taipei Melbourne Sao Paulo Cairo Paris Moscow San Francisco Calgary Hong Kong Nairobi New York Doha Sydney Santiago Tokyo Dublin Zurich Tokyo Vienna Frankfurt Lisbon Amsterdam Jakarta Guangzhou Milan Dallas Los Angeles Hanoi Singapore Denver New York Houston Moscow Dubai Prague Manila Moscow Hong Kong Vancouver Manila Mumbai Lisbon Milan Bangalore Tokyo Manila Tokyo Bangkok Istanbul Melbourne Mexico City Barcelona Buenos Aires Delhi Toronto Boston Mexico City Riyadh Tokyo Boston Munich Stockholm Tokyo Buenos Aires Lisbon Beijing Nanjing Frankfurt Guangzhou Beijing Santiago Kuala Lumpur Vienna Buenos Aires Toronto Lisbon Warsaw Dubai Houston London Port Louis Dubai Lisbon Madrid Prague Hong Kong Perth Manila Toronto Madrid Taipei Montreal Sao Paulo Montreal Tokyo Montreal Zurich Moscow Delhi New York Tunis Bangkok Frankfurt Rome Sao Paulo Bangkok Mumbai Santiago Zurich Barcelona Dubai Bangkok Delhi Beijing Qingdao Bangkok Warsaw Brussels Washington (DC) Cairo Sydney Dubai Guangzhou Chicago Prague Dubai Hamburg Dallas Dubai Dubai Montreal Frankfurt Rome Dublin Milan Istanbul Melbourne Johannesburg Mexico City Kuala Lumpur San Francisco Johannesburg Sao Paulo Luxembourg Madrid Karachi New York Mexico City Prague Kuwait City London Bangkok Guangzhou London Seattle Beijing Lima Luxembourg Shanghai Beijing Vancouver Madrid Melbourne Buenos Aires -

IN-Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme Interview #8 | Lima, Peru 8

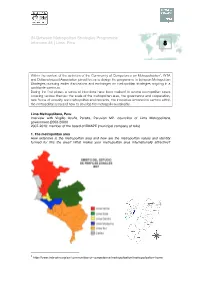

IN-Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme Interview #8 | Lima, Peru 8 Within the context of the activities of the Community of Competence on Metropolisation1, INTA and Deltametropool Association joined forces to design the programme In-between Metropolitan Strategies pursuing earlier discussions and exchanges on metropolitan strategies ongoing in a worldwide spectrum. During the first phase, a series of interviews have been realised to several metropolitan cases covering various themes: the scale of the metropolitan area, the governance and cooperation, new forms of urbanity and metropolitan environments, the innovative economical sectors within the metropolitan area and how to develop the metropolis sustainably. Lima Metropolitana, Peru Interview with Virgilio Acuña Peralta, Peruvian MP, councillor of Lima Metropolitana government (2003-2006) 2007-2010: member of the board of EMAPE (municipal company of tolls) 1.! The metropolitan area How extensive is the metropolitan area and how are the metropolitan values and identity formed for this the area? What makes your metropolitan area internationally attractive? 1 http://www.inta-aivn.org/en/communities-of-competence/metropolisation/metropolisation-home In Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme – Interview 7 Lima Metropolitana counts 9 millions inhabitants (including the Province of Callao) and 42 districts. The administrative region of Lima Metropolitana (excluding Callao) has a total surface of 2800 km2. The metropolitan area has an extension of 150km North-South and 60Km on the West (sea coast) - East (toward the Andes) direction. The development of the city with urban sprawl goes south, towards the seaside resorts, outside of the administrative limits of Lima Metropolitana (Province of Cañete, City of Ica) and to the Northern beach areas. -

Spanish Impact on Peru (1520 - 1824)

Spanish Impact on Peru (1520 - 1824) San Francisco Cathedral (Lima) Michelle Selvans Setting the stage in Peru • Vast Incan empire • 1520 - 30: epidemics halved population (reduced population by 80% in 1500s) • Incan emperor and heir died of measles • 5-year civil war Setting the stage in Spain • Iberian peninsula recently united after 700 years of fighting • Moors and Jews expelled • Religious zeal a driving social force • Highly developed military infrastructure 1532 - 1548, Spanish takeover of Incan empire • Lima established • Civil war between ruling Spaniards • 500 positions of governance given to Spaniards, as encomiendas 1532 - 1548, Spanish takeover of Incan empire • Silver mining began, with forced labor • Taki Onqoy resistance (‘dancing sickness’) • Spaniards pushed linguistic unification (Quechua) 1550 - 1650, shift to extraction of mineral wealth • Silver and mercury mines • Reducciones used to force conversion to Christianity, control labor • Monetary economy, requiring labor from ‘free wage’ workers 1550 - 1650, shift to extraction of mineral wealth • Haciendas more common: Spanish and Creole owned land, worked by Andean people • Remnants of subsistence-based indigenous communities • Corregidores and curacas as go- betweens Patron saints established • Arequipa, 1600: Ubinas volcano erupted, therefor St. Gerano • Arequipa, 1687: earthquake, so St. Martha • Cusco, 1650: earthquake, crucifix survived, so El Senor de los Temblores • Lima, 1651: earthquake, crucifixion scene survived, so El Senor de los Milagros By 1700s, shift -

YOUNG TOWN" GROWING up Four Decades Later: Self-Help Housing and Upgrading Lessons from a Squatter Neighborhood in Lima by SUSANA M

"YOUNG TOWN" GROWING UP Four decades later: self-help housing and upgrading lessons from a squatter neighborhood in Lima by SUSANA M. WILLIAMS Bachelor of Architecture University of Kansas, 2000 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning and the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of MASTER IN CITY PLANNING MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE and OFTECHNOLOGY MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES atthe JUN 2 8 2005 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2005 LIBRARIES @ 2005 Susana M. Williams. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of A uthor: ........................................ .................. Department ohrban Studies and Planning May19,2005 Certified by . ...... y . r..Ar .-. ... ..-......-.. ..................... ..................... Reinhard K Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Thesis Supervisor AA Certified by.. ........ 3 .. #.......................... Anna Hardman Professor of Economics, Tufts University Thesis Supervisor Accepted by............... ... ..................................................................... Dennis Frenchman Professor of the Practice of Urban Design Chairman, Master in City Planning Program Accepted by.... .. .. .. .Ju.. .. ..*Julian*Beinart Professor of Architecture Chairman, Master of Science in Architecture Studies Program .ARCHIVEr' "YOUNG TOWN" GROWING UP Four -

FGV Direito Rio in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

FGV Direito Rio in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil FGV Direito Rio is one of the most well respected education institutions in one of the most exciting international cities in the world. There are more than 3,000 undergraduate students and almost 2,000 graduate and master’s students enrolled. During the 2019-20 academic year, no U of M Law students participated in the semester exchange. Summary of Course Offerings http://direitorio.fgv.br/graduacao/gradecurricular Semester Dates Fall semester: August through December 2020 Spring semester: February to July 2021 Language of instruction Portuguese; four to six courses are offered in English each semester Courses/Credits/Grades Up to 15 credits may be transferred per semester abroad Each class period is 100 minutes; each course has either 30 or 60 “course hours” Grading is from 0 (minimum) to 10 (maximum) with a passing grade being 7 2 ECTS Credits = 1 Minnesota Credit Registration Registration is done by the International Office prior to the student’s arrival. Participate in our Law School’s lottery for the term you will be away. Register for 12-15 credits. Before leaving for your semester abroad, contact the Law School registrar at [email protected] to convert your credits to Off-campus Legal Studies. Housing FGV Direito Rio does not have on-campus housing for international students. They will provide assistance once students arrive in locating and obtaining off-campus accommodations. Financial Aid and Tuition Payment Financial aid will remain in effect for the semester you are abroad. Please make arrangements to have the balance (after tuition is deducted) sent to you if disbursement occurs after you have departed the U.S. -

Publicacion Oficial

El Peruano Jueves 25 de junio de 2015 555871 Dado en Ayacucho, en la sede del Gobierno Regional - Que, el numeral 36.1) del artículo 36º de la Ley Nº de Ayacucho, a los 30 días del mes de diciembre del año 27444, Ley del Procedimiento Administrativo General dos mil catorce. dispone que los procedimientos, requisitos y costos administrativos se establecen, exclusivamente, en el WILFREDO OSCORIMA NÚÑEZ caso de gobiernos locales, a través de la expedición de Presidente la Ordenanza Municipal correspondiente, los mismos que Gobierno Regional Ayacucho deben ser comprendidos y sistematizados en el Texto Único de Procedimientos Administrativos (TUPA). 1254463-1 - Que, el numeral 36.3 del artículo 36º de la precitada Ley del Procedimiento Administrativo General determina que: “Las disposiciones concernientes a la eliminación de procedimientos o requisitos o a la simpliicación de los mismos, GOBIERNOS LOCALES podrán aprobarse por Resolución Ministerial, Norma Regional de rango equivalente o Decreto de Alcaldía, según se trate de entidades dependientes del Gobierno Central, Gobiernos MUNICIPALIDAD DE Regionales o Locales, respectivamente”. - Que, el numeral 38.5) del artículo 38º de la Ley Nº CIENEGUILLA 27444 señala que: “Una vez aprobado el TUPA, toda modiicación que no implique la creación de nuevos procedimientos, incremento de derechos de tramitación o Aprueban la adecuación y modificación requisitos, se debe realizar por Resolución Ministerial del Sector, Norma Regional de rango equivalente o Decreto del TUPA de la Municipalidad de Alcaldía, o por Resolución del Titular del Organismo Autónomo conforme a la Constitución, según el nivel de DECRETO DE ALCALDÍA gobierno respectivo”; Nº 007-2015-A-MDC Que, con Informe Nº 97-2015-GAJ-MDC, de fecha 10 Cieneguilla, 15 de Junio de 2015. -

Association Between Maternal Exposure to Particulate Matter (PM2.5) and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Lima, Peru

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2020) 30:689–697 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-020-0223-5 ARTICLE Association between maternal exposure to particulate matter (PM2.5) and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Lima, Peru 1,2 1,2 3 3 3 1,2 V. L. Tapia ● B. V. Vasquez ● B. Vu ● Y. Liu ● K. Steenland ● G. F. Gonzales Received: 14 October 2019 / Revised: 16 March 2020 / Accepted: 7 April 2020 / Published online: 30 April 2020 © The Author(s) 2020. This article is published with open access Abstract The literature shows associations between maternal exposures to PM2.5 and adverse pregnancy outcomes. There are few data from Latin America. We have examined PM2.5 and pregnancy outcomes in Lima. The study included 123,034 births from 2012 to 2016, at three public hospitals. We used estimated daily PM2.5 from a newly created model developed using ground measurements, satellite data, and a chemical transport model. Exposure was assigned based on district of residence (n = 39). Linear and logistic regression analyzes were used to estimate the associations between air pollution exposure and pregnancy outcomes. Increased exposure to PM2.5 during the entire pregnancy and in the first trimester was inversely associated with birth weight. We found a decrease of 8.13 g (−14.0; −1.84) overall and 18.6 g (−24.4, −12.8) in the first trimester, for an 3 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: interquartile range (IQR) increase (9.2 µg/m )inPM2.5.PM2.5 exposure was positively associated with low birth weight at term (TLBW) during entire pregnancy (OR: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.03–1.20), and at the first (OR: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.03–1.20), second (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.01–1.17), and third trimester (OR: 1.10; 95% CI: 1.02–1.18) per IQR (9.2 µg/m3) increase. -

Addressing Social and Infrastructural Deficiencies in Villa Salvador-- Part 1

Syracuse University SURFACE School of Architecture Dissertations and Architecture Senior Theses Theses Spring 2014 Ciudad Disidente: Addressing social and infrastructural deficiencies in villa salvador-- Part 1 Victoria Brewster Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/architecture_theses Part of the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Brewster, Victoria, "Ciudad Disidente: Addressing social and infrastructural deficiencies in villa salvador-- Part 1" (2014). Architecture Senior Theses. 277. https://surface.syr.edu/architecture_theses/277 This Thesis, Senior is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Architecture Dissertations and Theses at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIUDAD DISIDENTE ADDRESSING SOCIAL AND INFRASTRUCTURAL DEFICIENCIES IN VILLA EL SALVADOR TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTION I. URGENCY II. CASE STUDIES III. LIMA, PERU IV. VILLA EL SALVADOR V. WORKS CITED VICTORIA BREWSTER DANIEL KALINOWSKI DECEMBER 9, 2013 ARC 505 - THESIS RESEARCH STUDIO PRIMARY ADVISOR: SAROSH ANKLESARIA SECONDARY ADVISORS: SUSAN HENDERSON, JULIE LARSEN CONTENTION Ciudad Disidente Within the next twenty years, Providing increased agency the Global South will account through community par- for 95% of urban growth, ticipation in the design and and nearly half of that will be construction processes will within the informal sector.1 encourage residents to be The population living within INVESTED in their neighbor- slums is expected to increase hood’s future. They will be to two billion people by 2030, more likely to focus on the and if left unchecked, it may maintenance and develop- reach three billion by 2050.2 ment of their homes, busi- This extreme growth requires nesses, and public spaces. -

Municipalidad De Villa El Salvador

Sábado 30 de abril de 2016 El Peruano / NORMAS LEGALES 585971 de la Gerencia de Asesoría Jurídica y de conformidad con y administrativa en los asuntos de su competencia, en el Artículo 9º numeral 11) de la Ley Nº 27972, el Pleno concordancia con los artículos II y IX del título preliminar del Concejo Municipal luego del debate de los señores de la Ley Nº 27972, Ley Orgánica de Municipalidades, que regidores sobre la importancia de este evento y escuchar establecen que aquella radica en la facultad de ejercer la exposición del señor Alcalde con dispensa del trámite de actos de gobierno, administrativos y de administración, lectura y aprobación del acta, adoptó por UNANIMIDAD el con sujeción al ordenamiento jurídico, y a su vez, se siguiente: legitima a través del proceso de planeación local que es uno integral, permanente y participativo, articulando a las ACUERDO: municipalidades con sus vecinos, aplicando las políticas de nivel local, teniendo en cuenta las competencias y funciones Artículo Primero.- AUTORIZAR el viaje en específicas, exclusivas y compartidas establecidas para las representación del Concejo Municipal de la Regidora señora municipalidades provinciales y distritales; LEYDITH INDIRA HORTENCIA VALVERDE MONTALVA Que, el artículo 161º numeral 7.2 cardinal 7) de a las ciudades de Roma y Milán - Italia, desde el 08 al 14 la acotada ley, precisa que es competencia y función de mayo del 2016, para participar en el evento denominado metropolitana especial, la planificación, regulación y gestión “Misión Técnica Internacional de -

Oficinas Bbva Horario De Atención : De Lunes a Viernes De 09:00 A.M

OFICINAS BBVA HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN : DE LUNES A VIERNES DE 09:00 A.M. a 6:00 P.M SABADO NO HAY ATENCIÓN OFICINA DIRECCION DISTRITO PROVINCIA YURIMAGUAS SARGENTO LORES 130-132 YURIMAGUAS ALTO AMAZONAS ANDAHUAYLAS AV. PERU 342 ANDAHUAYLAS ANDAHUAYLAS AREQUIPA SAN FRANCISCO 108 - AREQUIPA AREQUIPA AREQUIPA PARQUE INDUSTRIAL CALLE JACINTO IBAÑEZ 521 AREQUIPA AREQUIPA SAN CAMILO CALLE PERU 324 - AREQUIPA AREQUIPA AREQUIPA MALL AVENTURA PLAZA AQP AV. PORONGOCHE 500, LOCAL COMERCIAL LF-7 AREQUIPA AREQUIPA CERRO COLORADO AV. AVIACION 602, LC-118 CERRO COLORADO AREQUIPA MIRAFLORES - AREQUIPA AV. VENEZUELA S/N, C.C. LA NEGRITA TDA. 1 - MIRAFLORES MIRAFLORES AREQUIPA CAYMA AV. EJERCITO 710 - YANAHUARA YANAHUARA AREQUIPA YANAHUARA AV. JOSE ABELARDO QUIÑONES 700, URB. BARRIO MAGISTERIAL YANAHUARA AREQUIPA STRIP CENTER BARRANCA CA. CASTILLA 370, LOCAL 1 BARRANCA BARRANCA BARRANCA AV. JOSE GALVEZ 285 - BARRANCA BARRANCA BARRANCA BELLAVISTA SAN MARTIN ESQ AV SAN MARTIN C-5 Y AV. AUGUSTO B LEGUÍA C-7 BELLAVISTA BELLAVISTA C.C. EL QUINDE JR. SOR MANUELA GIL 151, LOCAL LC-323, 325, 327 CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA JR. TARAPACA 719 - 721 - CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAMANA - AREQUIPA JR. 28 DE JULIO 405, ESQ. CON JR. NAVARRETE CAMANA CAMANA MALA JR. REAL 305 MALA CAÑETE CAÑETE JR. DOS DE MAYO 434-438-442-444, SAN VICENTE DE PAUL DE CAÑETE SAN VICENTE DE CAÑETE CAÑETE MEGAPLAZA CAÑETE AV. MARISCAL BENAVIDES 1000-1100-1150 Y CA. MARGARITA 101, LC L-5 SAN VICENTE DE CAÑETE CAÑETE EL PEDREGAL HABILIT. URBANA CENTRO POBLADO DE SERV. BÁSICOS EL PEDREGAL MZ. G LT. 2 MAJES CAYLLOMA LA MERCED JR. TARMA 444 - LA MERCED CHANCHAMAYO CHANCHAMAYO CHICLAYO AV. -

Innova Schools in Peru: the Economic and Social Context, Privatization, and the Educational Context in Peru

Directorate for Education and Skills Innovative Learning Environments (ILE) System Note PERU Innova Schools- Colegios Peruanos 1. Aims Innova Schools (IS) has under its vision to offer quality education at a reasonable cost to the children in Peru. The targeted children are those that pertain to lower B, and C, SES. Our aim is to offer an alternative that is excellent, scalable and affordable, in order to narrow the gap regarding the problem of quality education in Peru. As a private educational system, we are resolved to overcome the learning gap, with initiatives and interventions that have innovation at the core. IS is implementing a paradigm shift: from teacher centred schools, to schools that are student centred. In this paradigm shift, technology is regarded as an important tool in the learning process. Our learning process promotes that students use technology to learn efficiently, and that teachers facilitate this process accordingly. To perform its vision, IS started as a full-fledged company in 2010 with a carefully designed business plan including the construction of a nationwide network of 70 schools that will serve over 70,000 students by 2020. Up to the moment, we have 18 schools, 16 in the peripheral areas of the capital city of Lima, and 2 in the provinces. IS is currently attending a population of approximately 620 teachers, and 9 100 students. 2. Leadership and Partners At the educational system level, Jorge Yzusqui our CEO is a member of the National Council of Education [Consejo Nacional de Eduación-CNE]. There is also a close connection between our CEO and Martín Vegas who is the vice-minister of pedagogic management at the Ministry of Education in Peru.