Buenos Aires to Lima By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gawc Link Classification FINAL.Xlsx

High Barcelona Beijing Sufficiency Abu Dhabi Singapore sufficiency Boston Sao Paulo Barcelona Moscow Istanbul Toronto Barcelona Tokyo Kuala Lumpur Los Angeles Beijing Taiyuan Lisbon Madrid Buenos Aires Taipei Melbourne Sao Paulo Cairo Paris Moscow San Francisco Calgary Hong Kong Nairobi New York Doha Sydney Santiago Tokyo Dublin Zurich Tokyo Vienna Frankfurt Lisbon Amsterdam Jakarta Guangzhou Milan Dallas Los Angeles Hanoi Singapore Denver New York Houston Moscow Dubai Prague Manila Moscow Hong Kong Vancouver Manila Mumbai Lisbon Milan Bangalore Tokyo Manila Tokyo Bangkok Istanbul Melbourne Mexico City Barcelona Buenos Aires Delhi Toronto Boston Mexico City Riyadh Tokyo Boston Munich Stockholm Tokyo Buenos Aires Lisbon Beijing Nanjing Frankfurt Guangzhou Beijing Santiago Kuala Lumpur Vienna Buenos Aires Toronto Lisbon Warsaw Dubai Houston London Port Louis Dubai Lisbon Madrid Prague Hong Kong Perth Manila Toronto Madrid Taipei Montreal Sao Paulo Montreal Tokyo Montreal Zurich Moscow Delhi New York Tunis Bangkok Frankfurt Rome Sao Paulo Bangkok Mumbai Santiago Zurich Barcelona Dubai Bangkok Delhi Beijing Qingdao Bangkok Warsaw Brussels Washington (DC) Cairo Sydney Dubai Guangzhou Chicago Prague Dubai Hamburg Dallas Dubai Dubai Montreal Frankfurt Rome Dublin Milan Istanbul Melbourne Johannesburg Mexico City Kuala Lumpur San Francisco Johannesburg Sao Paulo Luxembourg Madrid Karachi New York Mexico City Prague Kuwait City London Bangkok Guangzhou London Seattle Beijing Lima Luxembourg Shanghai Beijing Vancouver Madrid Melbourne Buenos Aires -

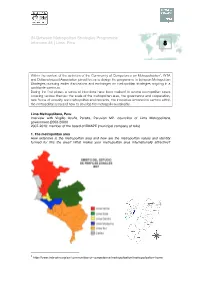

IN-Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme Interview #8 | Lima, Peru 8

IN-Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme Interview #8 | Lima, Peru 8 Within the context of the activities of the Community of Competence on Metropolisation1, INTA and Deltametropool Association joined forces to design the programme In-between Metropolitan Strategies pursuing earlier discussions and exchanges on metropolitan strategies ongoing in a worldwide spectrum. During the first phase, a series of interviews have been realised to several metropolitan cases covering various themes: the scale of the metropolitan area, the governance and cooperation, new forms of urbanity and metropolitan environments, the innovative economical sectors within the metropolitan area and how to develop the metropolis sustainably. Lima Metropolitana, Peru Interview with Virgilio Acuña Peralta, Peruvian MP, councillor of Lima Metropolitana government (2003-2006) 2007-2010: member of the board of EMAPE (municipal company of tolls) 1.! The metropolitan area How extensive is the metropolitan area and how are the metropolitan values and identity formed for this the area? What makes your metropolitan area internationally attractive? 1 http://www.inta-aivn.org/en/communities-of-competence/metropolisation/metropolisation-home In Between Metropolitan Strategies Programme – Interview 7 Lima Metropolitana counts 9 millions inhabitants (including the Province of Callao) and 42 districts. The administrative region of Lima Metropolitana (excluding Callao) has a total surface of 2800 km2. The metropolitan area has an extension of 150km North-South and 60Km on the West (sea coast) - East (toward the Andes) direction. The development of the city with urban sprawl goes south, towards the seaside resorts, outside of the administrative limits of Lima Metropolitana (Province of Cañete, City of Ica) and to the Northern beach areas. -

The BUENOS AIRES DECLARATION

The BUENOS AIRES DECLARATION The WTTC Travel & Tourism Declaration on Illegal Trade in Wildlife Introduction The scale of wildlife crime has drastically increased in recent years. The UN World Wildlife Crime Report shows that over 7,000 species of animals and plants from across all regions are impacted, and this illegal trade is estimated to be worth up to $20 billion annually. Flora and fauna are often key drivers of Travel & Tourism activity and as such it is in the interest of the sector to support initiatives to combat the illegal trade in them. While there are many initiatives taking place at ground level, until now there has been no co-ordinated, high profile engagement from the Travel & Tourism sector as a whole. Following a call to action by John Scanlon, Secretary General of the Convention on Illegal Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) at the 2017 WTTC Global Summit, WTTC has developed a Declaration for the Travel & Tourism sector worldwide to 01demonstrate co-ordinated commitment and action to combat the illegal trade in wildlife. The Declaration was launched at the 2018 WTTC Global Summit in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 19 April 2018. 02What is the declaration? The Declaration contains 12 actions which the Travel & Tourism sector can take to combat the illegal wildlife trade, grouped into 4 areas: 1. Expression and demonstration of agreement to tackle the illegal wildlife trade 2. Promotion of responsible wildlife-based tourism 3. Awareness raising among customers, staff and trade networks 4. Engaging with communities and investing locally Who can sign? WTTC Members and other Travel & Tourism related entities with an interest in and commitment to this issue – industry organisations, companies, tourist boards and NGOs – are all invited to sign 03the Declaration. -

Entre São Paulo E Buenos Aires

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Cadernos Espinosanos (E-Journal) RESENHA ENTRE SÃO PAULO E BUENOS AIRES Natália Romanovskia Os ensaios de Vanguardas em retrocesso, de Sérgio Miceli (2012), procuram comparar o modernismo argentino e o brasileiro. A reunião desses textos em livro, originalmente apresentados e publicados entre 2006 e 2011, ressalta o valor dos parâmetros comparativos propostos, que passam por três linhas mestras, a fim de orientar a reflexão sobre os fenômenos em ambos os países, e se referem a relações objetivas fundamentais, as quais nortearam as realizações dessas vanguardas. Na primeira dessas linhas, encontra-se a posição do autor com relação à historiografia literária e artística, a qual construiu um relato triunfalista sobre as primeiras gerações modernistas nos dois países. Miceli pretende reconstituir as dimensões sociais do trabalho intelectual no período em questão e reavaliar as contribuições efetivas desses intelectuais, bem como explicitar as condições sociais que possibilitaram suas emergências. Em nenhum dos ensaios essa proposta fica mais clara do que naqueles dedicados a Jorge Luis Borges. A escolha desse autor é significativa, pois sua figura se tornou a do escritor puro e desistoricizado, uma façanha alcançada a partir da junção entre a lógica particular do campo literário, que tende a apagar as constrições sociais que determinam as práticas literárias, e os esforços do próprio Borges para ser identificado com o escritor puro, passando pelo apagamento deliberado dos -

Spanish Impact on Peru (1520 - 1824)

Spanish Impact on Peru (1520 - 1824) San Francisco Cathedral (Lima) Michelle Selvans Setting the stage in Peru • Vast Incan empire • 1520 - 30: epidemics halved population (reduced population by 80% in 1500s) • Incan emperor and heir died of measles • 5-year civil war Setting the stage in Spain • Iberian peninsula recently united after 700 years of fighting • Moors and Jews expelled • Religious zeal a driving social force • Highly developed military infrastructure 1532 - 1548, Spanish takeover of Incan empire • Lima established • Civil war between ruling Spaniards • 500 positions of governance given to Spaniards, as encomiendas 1532 - 1548, Spanish takeover of Incan empire • Silver mining began, with forced labor • Taki Onqoy resistance (‘dancing sickness’) • Spaniards pushed linguistic unification (Quechua) 1550 - 1650, shift to extraction of mineral wealth • Silver and mercury mines • Reducciones used to force conversion to Christianity, control labor • Monetary economy, requiring labor from ‘free wage’ workers 1550 - 1650, shift to extraction of mineral wealth • Haciendas more common: Spanish and Creole owned land, worked by Andean people • Remnants of subsistence-based indigenous communities • Corregidores and curacas as go- betweens Patron saints established • Arequipa, 1600: Ubinas volcano erupted, therefor St. Gerano • Arequipa, 1687: earthquake, so St. Martha • Cusco, 1650: earthquake, crucifix survived, so El Senor de los Temblores • Lima, 1651: earthquake, crucifixion scene survived, so El Senor de los Milagros By 1700s, shift -

FGV Direito Rio in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

FGV Direito Rio in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil FGV Direito Rio is one of the most well respected education institutions in one of the most exciting international cities in the world. There are more than 3,000 undergraduate students and almost 2,000 graduate and master’s students enrolled. During the 2019-20 academic year, no U of M Law students participated in the semester exchange. Summary of Course Offerings http://direitorio.fgv.br/graduacao/gradecurricular Semester Dates Fall semester: August through December 2020 Spring semester: February to July 2021 Language of instruction Portuguese; four to six courses are offered in English each semester Courses/Credits/Grades Up to 15 credits may be transferred per semester abroad Each class period is 100 minutes; each course has either 30 or 60 “course hours” Grading is from 0 (minimum) to 10 (maximum) with a passing grade being 7 2 ECTS Credits = 1 Minnesota Credit Registration Registration is done by the International Office prior to the student’s arrival. Participate in our Law School’s lottery for the term you will be away. Register for 12-15 credits. Before leaving for your semester abroad, contact the Law School registrar at [email protected] to convert your credits to Off-campus Legal Studies. Housing FGV Direito Rio does not have on-campus housing for international students. They will provide assistance once students arrive in locating and obtaining off-campus accommodations. Financial Aid and Tuition Payment Financial aid will remain in effect for the semester you are abroad. Please make arrangements to have the balance (after tuition is deducted) sent to you if disbursement occurs after you have departed the U.S. -

Puerto Madero a Critique

Puerto Madero A CRITIQUE © Alvaro Uribe The old port Alfredo Garay with Laura Wainer, district of Buenos Hayley Henderson, and Demian Rotbart Aires (above) is thriving again. Santiago ore than two decades have passed Calatrava’s since a government-led megaproject footbridge (inset), set out to transform Puerto Madero, Puente de la the oldest sector of the port district Mujer, spans the M © iStockphoto.com at the mouth of the River Plate in Buenos Aires, water at dock 3. Argentina. Once a center of decay that was has- tening decline in the adjacent downtown, Puerto Madero is now a tourist icon and hub of progress, drawing in residents and visitors alike to its park and cultural amenities, housing approximately Encompassing 170 hectares near the down- 5,000 new inhabitants, and generating 45,000 town presidential palace (Casa Rosada), Puerto service jobs. Home to a number of new architec- Madero was one of Latin America’s first urban tural landmarks—including Santiago Calatrava’s brownfield renewal projects of this scale and Woman’s Bridge (Puente de la Mujer) and César complexity. The project was conceived as part Pelli’s YPF headquarters—the redeveloped port of a wider strategy for city-center development has contributed to the reactivation of the city that also included changes in land use regulations, center, influencing development trends through- building refurbishments, and social housing in out the Argentinean capital. heritage areas. This article draws on two decades’ 2 LINCOLN INSTITUTE OF LAND POLICY • Land Lines • JULY 2013 -

El Ermitaño and Pampa De Cueva As Case Studies for a Regional Urbanization Strategy

Article Place-Making through the Creation of Common Spaces in Lima’s Self-Built Settlements: El Ermitaño and Pampa de Cueva as Case Studies for a Regional Urbanization Strategy Samar Almaaroufi 1, Kathrin Golda-Pongratz 1,2,* , Franco Jauregui-Fung 1 , Sara Pereira 1, Natalia Pulido-Castro 1 and Jeffrey Kenworthy 1,3,* 1 Department of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geomatics, Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences, 60318 Frankfurt, Germany; samarmaaroufi@gmail.com (S.A.); [email protected] (F.J.-F.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (N.P.-C.) 2 UIC School of Architecture, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, 08017 Barcelona, Spain 3 Curtin University Sustainability Policy Institute, Curtin University, Bentley 6102, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.G.-P.); jeff[email protected] (J.K.) Received: 30 October 2019; Accepted: 2 December 2019; Published: 10 December 2019 Abstract: Lima has become the first Peruvian megacity with more than 10 million people, resulting from the migration waves from the countryside throughout the 20th century, which have also contributed to the diverse ethnic background of today’s city. The paper analyzes two neighborhoods located in the inter-district area of Northern Lima: Pampa de Cueva and El Ermitaño as paradigmatic cases of the city’s expansion through non-formal settlements during the 1960s. They represent a relevant case study because of their complex urbanization process, the presence of pre-Hispanic heritage, their location in vulnerable hillside areas in the fringe with a protected natural landscape, and their potential for sustainable local economic development. The article traces back the consolidation process of these self-built neighborhoods or barriadas within the context of Northern Lima as a new centrality for the metropolitan area. -

Puerto Madero the New Face of the City

Year 2 / N° 5 El Observador Porteño March (The Observer of the City of Buenos Aires) Monthly Newspaper of the Cultural-Historical Heritage Observatory 2018 Puerto Madero The new face of the City Warehouses and grocery stores of Puerto Madero in the beginning of the 20th century. This electronic bulletin is aimed at promoting the activities carried out by the Juntas de Estudios Históricos (Historical Research Boards) and the Gerencia Operativa de Patrimo- nio (Heritage Operative Management) within the framework of Resolution 1534/GCABA/ MCGC/2011, which created the Observatorio del Patrimonio Histórico-Cultural (Cultur- al-Historical Heritage Observatory) of the City of Buenos Aires. We will publish infor- mation on every neighborhood of the city on a monthly basis, as well as relevant articles related to the aforementioned Board. Puerto Madero: the new face This is how we reached 1880. There were of the City two options: the canal could be made deeper, and the installations of the Riachuelo could The port of Buenos Aires, a keystone in Ar- be improved or a new system near Plaza de gentinian history, was not created naturally. Mayo should be built. The interests related The nearest natural anchorage is located in to the first option were promoted by the en- Ensenada. For this reason, when the north- gineer Luis Huergo, the traders, the citizens ern channel of the Riachuelo was blocked of the south of the city, and the newspaper (mid 18th century), new anchoring spots La Prensa. The ones related to the second were needed. These were found throughout alternative were promoted by the trader the coast in places named by the sailors as Eduardo Madero, members of the national “potholes”, were the river was deeper. -

Urban Development and Sustainable Mobility: a Spatial Analysis in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area

land Article Urban Development and Sustainable Mobility: A Spatial Analysis in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area Lorea Mendiola 1,*,† and Pilar González 2,† 1 Department of Applied Economics I, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), 20018 Donostia-San Sebastian, Spain 2 Department of Quantitative Methods & Institute for Public Economics, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), 48015 Bilbao, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-94-30-5844 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: This study provides empirical evidence on the links between urban development factors and the use of specific modes of transport in commuting in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area. The case study is of interest because quantitative research on developing countries is scarce and their rapid urban growth and high rates of inequality may generate different results compared to the US or Europe. This relationship was assessed on locality level using regression methods. Spatial econometric techniques were applied to avoid unreliable inferences generated by spatial dependence and to detect the existence of externalities. Furthermore, we include in the model the socio-economic profile of each locality identified using cluster analysis. The findings reveal that population density affects motorised transport, that diversity is relevant for public transport and non- motorised trips, and urban design characteristics affect all modes of transport. Spatial dependence is detected for motorised transport, which may imply the existence of externalities, suggesting the need for coordinated decision-making processes on a metropolitan level. Finally, modal split depends on the socio-economic profile of a locality, which may influence the response to public transport policies. -

December 2017

Immigrant Visa Issuances By Post December 2017 (FY 2018) Post Visa Class Issuances Abidjan CR1 5 Abidjan DV1 9 Abidjan DV2 3 Abidjan DV3 2 Abidjan F11 1 Abidjan F12 1 Abidjan F21 1 Abidjan F22 2 Abidjan F23 1 Abidjan F41 1 Abidjan F42 1 Abidjan F43 2 Abidjan FX1 3 Abidjan FX2 1 Abidjan IR2 6 Abidjan IR5 5 Abu Dhabi CR1 6 Abu Dhabi CR2 3 Abu Dhabi DV1 12 Abu Dhabi DV2 4 Abu Dhabi DV3 5 Abu Dhabi E11 1 Abu Dhabi E14 1 Abu Dhabi E15 1 Abu Dhabi E21 3 Abu Dhabi E31 10 Abu Dhabi E34 7 Abu Dhabi E35 7 Abu Dhabi F11 1 Abu Dhabi F21 2 Abu Dhabi F24 1 Abu Dhabi F33 5 Abu Dhabi F41 6 Abu Dhabi F42 4 Abu Dhabi F43 5 Abu Dhabi FX1 3 Abu Dhabi I51 15 Abu Dhabi I52 13 Abu Dhabi I53 23 Abu Dhabi IR1 4 Abu Dhabi IR2 4 Abu Dhabi IR5 7 Page 1 of 57 Immigrant Visa Issuances By Post December 2017 (FY 2018) Post Visa Class Issuances Accra CR1 45 Accra CR2 1 Accra DV1 24 Accra DV2 9 Accra DV3 14 Accra E31 1 Accra E34 1 Accra F11 19 Accra F12 9 Accra F21 22 Accra F22 20 Accra F23 3 Accra F24 2 Accra F31 6 Accra F32 6 Accra F33 10 Accra F41 11 Accra F42 7 Accra F43 7 Accra FX1 10 Accra FX2 15 Accra FX3 9 Accra IB3 1 Accra IR1 76 Accra IR2 101 Accra IR3 4 Accra IR5 79 Addis Ababa CR1 52 Addis Ababa DV1 109 Addis Ababa DV2 23 Addis Ababa DV3 24 Addis Ababa E11 2 Addis Ababa E14 2 Addis Ababa E15 4 Addis Ababa F11 10 Addis Ababa F12 1 Addis Ababa F21 27 Addis Ababa F22 25 Addis Ababa F24 10 Addis Ababa F25 1 Addis Ababa F41 3 Addis Ababa F42 2 Page 2 of 57 Immigrant Visa Issuances By Post December 2017 (FY 2018) Post Visa Class Issuances Addis Ababa F43 5 Addis -

Global Rescue Will Evacuate You to Your Home Hospital of Choice

Mumbai. Qogir. Shanghai. Karachi. Istanbul. Delhi. São Paulo. Moscow. Medical Evacuation. Seoul. Beijing. Mount Everest. Mexico City. Tokyo. Ja- karta. New York City. Lagos. Kinshasa. Nepal. Tehran. London. Manaslu. Security Evacuation. Lima. Bogotá. Hong Kong. Bangkok . Makalu. Cairo. Dhaka. Ho Chi Minh City. Annapurna. Rio de Janeiro. Tianjin. Chongqing. Baghdad. Lhotse. Bangalore.Kolkata. Yangon. Santiago. Pakistan. Singapore. Guangzhou. Nanga Parbat. Saint Petersburg. Wuhan. Chennai. Medical Evacuation. Riyadh. Alexandria. Surat. Hyderabad. Shenyang. Ahmedabad. Ankara. Field Rescue. Cho Oyu. Johannesburg. Los Angeles. Kangchenjunga. Abidjan. Yokohama. Busan. Cape Town. Durban. Berlin. Pune. Pyongyang. Madrid. Kanpur. Jaipur. Field Rescue. Buenos Aires. Dhaulagiri. Nairobi. Jeddah. Mumbai. Qogir. Shanghai. Security Evacuation. Karachi. Istanbul. Delhi. São Paulo. Moscow. Seoul. Beijing. Mount Everest. Mexico City. Tokyo. Jakarta. New York City. Lagos. Kinshasa. Nepal. Tehran. London. Manaslu. Lima. Bogotá. Hong Kong. Bangkok Makalu. Cairo. Dhaka. Ho Chi Minh City. Annapurna. Rio de Janeiro. Tianjin. Chongqing. Baghdad. Lhotse. Bangalore. Field Rescue. Kolkata. Yangon. Santiago. Pakistan. Singapore. Guangzhou. Nanga Parbat. Security Evacuation. Saint Petersburg. Wuhan. Medical Evacuation. Chennai. Riyadh. Alexandria. Surat. Hyderabad. Shenyang. Ahmedabad. Ankara. Cho Oyu. Johannesburg. Los Angeles. Kangchenjunga. Abidjan. Yokohama. Busan. Cape Town. Durban. Berlin. Pune. Pyongyang. Madrid. Kanpur. Jaipur. Buenos Aires. Dhaulagiri. Nairobi.Global Jeddah. Mumbai. Qogir. Shanghai. Rescue Karachi. Istanbul. Delhi. São Paulo. Moscow. Medical Evacuation. Seoul. Beijing. Mount Everest. Mexico City. Tokyo. Jakarta. New York City. Lagos. Kinshasa. Nepal. Tehran. London. Manaslu. Security Evacuation. Lima. Bogotá. Hong CriticalKong. Bangkok . ServicesMakalu. Cairo. Dhaka.Provided Ho Chi Minh to City. Stratfor Annapurna. Rio deEnterprises, Janeiro. Tianjin. Chongqing. LLC Baghdad. Lhotse. Bangalore.Kolkata. Yangon. Santiago. Pakistan. Singapore. Guangzhou.