A Case of Erusu Akoko, Ondo State O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

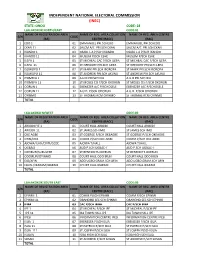

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

African Scholar VOL. 18 NO. 6 Publications & ISSN: 2110-2086 Research SEPTEMBER, 2020 International African Scholar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHSS-6) Study of Forms and Functions of Esu – Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Fine and Applied Arts Department, School of Vocational and Technical Education, Tai Solarin College of Education, Omu – Ijebu Abstract The representational images such as pots, rattles, bracelets, stones, cutlasses, wooden combs, staffs, mortals, brooms, etc. are religious and its significance for the worshippers were that they had faith in it. The denominator in the worship of all gods and spirits everywhere is faith. The power of an image was believed to be more real than that of a living being. The Yoruba appear to be satisfied with the gods with whom they are in immediate touch because they believe that when the Orisa have been worshipped, they will transmit what is necessary to Olodumare. This paper examines the traditional practices of the people of Yewa and discovers why Esu is market appellate. It focuses on the classifications of the forms and functions of Esu-Oja representational objects in selected towns in Yewaland. Keywords: appellate, classifications, divinities, fragment, forms, images, libations, mystical powers, Olodumare, representational, sacred, sacrifices, shrine, spirit archetype, transmission and transformation. Introduction Yewa which was formally called there are issues of intra-regional “Egbado” is located on Nigeria’s border conflicts that call for urgent attention. with the Republic of Benin. Yewa claim The popular decision to change the common origin from Ile-Ife, Oyo, ketu, Egbado name according to Asiwaju and Benin. -

Land Accessibility Characteristics Among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria

Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences 2(1): 1-12, 2017; Article no.ARJASS.30086 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Land Accessibility Characteristics among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria Gbenga John Oladehinde 1* , Kehinde Popoola 1, Afolabi Fatusin 2 and Gideon Adeyeni 1 1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out collaboratively by all authors. Author GJO designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors KP and AF supervised the preparation of the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches while author GA led and managed the data analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARJASS/2017/30086 Editor(s): (1) Raffaela Giovagnoli, Pontifical Lateran University, Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano 4, Rome, Italy. (2) Sheying Chen, Social Policy and Administration, Pace University, New York, USA. Reviewers: (1) F. Famuyiwa, University of Lagos, Nigeria. (2) Lusugga Kironde, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17570 Received 16 th October 2016 Accepted 14 th January 2017 Original Research Article st Published 21 January 2017 ABSTRACT Aim: The study investigated challenges of land accessibility among migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. Methodology: Data were obtained through questionnaire administration on a Migrant household head. Multistage sampling technique was used for selection of 161 respondents for the study. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Aduloju of Ado: a Nineteenth Century Ekiti Warlord

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 18, Issue 4 (Nov. - Dec. 2013), PP 58-66 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Aduloju of Ado: A Nineteenth Century Ekiti Warlord Emmanuel Oladipo Ojo (Ph.D) Department of History & International Studies, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, NIGERIA Abstract: For Yorubaland, south-western Nigeria, the nineteenth century was a century of warfare and gun- powder akin, in magnitude and extent, to that of nineteenth century Europe. Across the length and breadth of Yorubaland, armies fought armies until 1886 when Sir Gilbert Carter, British Governor of the Lagos Protectorate, intervened to restore peace. Since men are generally the products of the times in which they live and the circumstances with which they are surrounded; men who live during the period of peace and tranquillity are most likely to learn how to promote and sustain peace while those who live in periods of turbulence and turmoil are most likely to learn and master the art of warfare. As wars raged and ravaged Yoruba nations and communities, prominent men emerged and built armies with which they defended their nations and aggrandised themselves. Men like Latosisa, Ajayi Ogboriefon and Ayorinde held out for Ibadan; Obe, Arimoro, Omole, Odo, Edidi, Fayise and Ogedengbe Agbogungboro for Ijesa; Karara for Ilorin; Ogundipe for Abeokuta; Ologun for Owo; Bakare for Afa; Ali for Iwo, Oderinde for Olupona, Onafowokan and Kuku for Ijebuode, Odu for Ogbagi; Adeyale for Ila; Olugbosun for Oye and Ogunbulu for Aisegba. Like other Yoruba nations and kingdoms, Ado Kingdom had its own prominent warlords. -

Current Research in African Linguistics

Current Research in African Linguistics Current Research in African Linguistics: Papers in Honor of Ọladele Awobuluyi Edited by Ọlanikẹ Ọla Orie, Johnson Fọlọrunṣo Ilọri and Lendzemo Constantine Yuka Current Research in African Linguistics: Papers in Honor of Ọladele Awobuluyi Edited by Ọlanikẹ Ọla Orie, Johnson Fọlọrunṣo Ilọri and Lendzemo Constantine Yuka This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ọlanikẹ Ọla Orie, Johnson Fọlọrunṣo Ilọri, Lendzemo Constantine Yuka and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7812-X ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7812-8 We pro-noun-ce his name (for Ọladele Awobuluyi) Tosin Gbogi i it was summer ’37 in a place where the lullabies of birds overwhelmed guitar and song, where hornbills hearkened to the call of thrushes singing in rush above streams that strolled gently gently without a word to the king …. he met language in summer ’37 when earth was kind to man and man was kind to earth it was from the armpit of the hills that the phonemes carried him into a syllable of sounds, and from there into logarhythms of words— syntax of stones which against each one another hit and burst into utterances of light he met language at oke-agbe where earth was kind to man and man was kind to earth ii the globe in his hands the benevolent wind sailed him to the shores of another sea there where latin lay snoring, waiting for its requiem and rites …. -

Akoko Resistance to External Invasion and Domination in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume II, Issue XI, November 2018|ISSN 2454-6186 Akoko Resistance to External Invasion and Domination in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Johnson Olaosebikan Aremu1, Solomon Oluwasola Afolabi2 1Ph.D, Department of History and International Studies, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, P.M.B. 5363, Ado- Ekiti, Nigeria. 2Ph.D, Registry Department, Ekiti State University, Ado – Ekiti, Nigeria Abstract: - This study examined the nature of Akoko response to historiography carried out in 1988 as “a virgin land for external invasion and domination by some neighbouring and research.”2 Since then, nothing seems to have changed th th distant Nigerian groups and communities in the 19 and 20 significantly. Centuries. Data for the study was obtained from primary and secondary sources and were analysed using qualitative methods It is essential to note that the origin of the word “Akoko” is of analysis. The primary sources are archival materials and oral shrouded in mystery. Local traditions attribute it to the interviews with informants who were purposively selected due to persistent invasions of the area by external forces, particularly their perceived knowledge about the subject of study. Secondary the Ibadan warlords; who then described the area as sources included relevant textbooks, journal articles, thesis, Akorikotan3 or Akokotunko, both of which refer to dissertations and long essays, some periodicals and internet inexhaustible source of slaves and booties. If this tradition is materials. It noted that Akoko communities were invaded severally by some of their immediate neighbours like Owo; Ado- anything worthy of consideration, it could therefore, be said Ekiti and Ikole- Ekiti between the 15th and 18th centuries; as well that Akoko derives its present generic name from persistent as some imperial lords from Benin, Nupe and Ibadan in the 19th invasions of the external forces in the pre-colonial era. -

African Musician As Journalist: a Study of Ayinde Barrister's Works

New Media and Mass Communication www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3267 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3275 (Online) Vol.48, 2016 African Musician as Journalist: A Study of Ayinde Barrister’s Works Kola Adesina, Ph.D Adeyemi Obalanlege, Ph.D Idris Katib Department of Mass Communication, Crescent University, Abeokuta Abstract This study was conducted to test the validity of contention that Sikiru Ayinde Barrister (SAB) music is journalism, particularly when its contents are juxtaposed with different sections of a newspaper or magazine.Being a qualitative essay, copious quotations from SAB's works were done to test each unit of the analysis such as education, politics, news commentary, travel/tourism, editorial, poetry etc. A total of 13 albums representing 10% of SAB's works were selected and graded on their contents based on their suitability to each of the categories above.Findings however revealed that music of SAB is journalism. Apart from informing, educating and entertaining his audience, SAB also employed his music for agenda-setting and social responsibility purposes in media theoretical framework. The criticism aspect of his music had played the watch- dog and advocacy roles of the media on the populace and the government especially during the military juntas of Gen. Muhamadu Bihari, Ibrahim Babangida and Sani Abacha respectively.The study found that selected works of traditional musicians such as Ayinde Barrister and Ayinla Omowura qualify journalism in structure and content. Introduction Journalists are sometimes regarded as mobile encyclopaedia because they access, process and sift deluge of information at their disposal and at the same time, feed the society back. -

AAUA Appoints Orina As Bursar

Vision To be a foremost institution that moves manpower development in direction of self apprenticeship; a first-class University in research, knowledge, character and service to humanity. The Weekly Newsletter of Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State Mission To provide knowledge and skills for self-reliance in a conducive environment where teaching, Vol, XVII No. 3 Monday, June 28, 2021 learning and research can take place. Accreditation: Ajasin Varsity will Sustain Collaboration with ICAN he Acting Vice a course in the University. and students of the the course in Nigeria Chancellor of In his words, “It may Department. abreast of the best global TAdekunle Ajasin interest you to know that our Speaking earlier, the practices and be at par with University, Akungba Akoko, Department of Accounting leader of the team, Prof. their peers globally. is one of the best Prof. Olugbenga Ige, has Akinsola Akintoye, FCA, He promised that ICAN Departments in the affirmed that the Institution had pointed out that the would look into the activities University, and the students would maintain the existing accreditation visit was not of the Department with the strong relationship between there are also turning out to punitive but a mechanism to aim of granting exemptions it and the Institute of be excellent and best keep institutions that were to deserving students and Chartered Accountants of among their peers. running Accounting possibly recommend them Nigeria (ICAN). Therefore, your presence is programme on their toes Prof. Ige gave the going to be a plus for us, for ICAN final examination. and to keep graduates of affirmation on Tuesday, most especially, for the staff June 15, 2021, while playing host to an Accreditation Team from the Institute who was in the University to evaluate the Department of Accounting. -

MTECH-THESES-7TH-MAY-2021.Pdf

THE FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, AKURE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED MASTERS APPLICATIONS FOR REGISTRATION OF THESIS TITLES AND APPOINTMENT OF EXAMINERS, 7TH MAY, 2021 S/N NAME AND DEPT DEGREE IN-VIEW PROPOSED THESIS UNIVERSITY EXTERNAL MATRIC. NUMBER TITLE EXAMINERS EXAMINERS 1. ADESOLA-ZION, AEC M. Agric. Tech., Adoption and Utilization of Chief Examiner Substantive Yetunde Naomi Extension and Orange Fleshed Sweet Potato Prof. O. O. Fasina Prof. Mrs. O. E. Fapojuwo AEC/17/5863 Communication by Farmers in Osun State, Major Supervisor Department of Agricultural Technology Nigeria Prof. O. O. Fasina Administration, Federal Co-Supervisor University of Agriculture, Dr. O. M. Akinnagbe Abeokuta, Nigeria Other School Examiner Alternative - Prof. O.B. Oyesola Rep. of SPGS Department of Agricultural Prof. S. O. Salawu (BCH) Extension and Rural Development, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria. 2. OGUNLEYE, Idowu AGE M. Eng. Agricultural Development and Chief Examiner Substantive Babatunde and Environmental Performance Evaluation of a Prof. J. T. Fasinmirin Prof. J. O. Olajide AGE/16/1413 Engineering Big Gun Sprinkler for Dry Major Supervisor Department of Food Science Season Farming Prof. O. J. Olukunle and Technology, Ladoke Co-Supervisor Akintola University of - Technology, Ogbomoso, Other School Examiners Nigeria. - Alternate Rep. of SPGS Prof. V. I. O. Ndirika Prof. J. A. V. Olumurewa Department of Agricultural (BTH) and Bioresources Engineering, Michael Opara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Nigeria 1 3. EVAL, John Fidelis AGP M. Tech., Exploration Gis-Based Catastrophe Chief Examiner Substantive AGP/16/0901 Geophysics Modeling of Geophysical Prof. G.O. Omosuyi Dr. M. Z. Mohammed, and Remote Sensing Data for Major Supervisor Department of Earth Landslide Susceptibility Dr. -

Annual-Report-2011.Pdf (Pdf, 2.64

CONTENTS Lafarge Cement WAPCO Nigeria Plc 02 The Lafarge Advantage 05 Notice of Annual General Meeting 09 Directors’ and Statutory Information 10 Chairman’s Statement 11 Board of Directors 14 Board of Directors’ Profile 16 Financial Highlights 20 Report of the Directors 21 Management Team 27 Health and Safety Report 29 Environment Report 30 Human Resources and People Development Report 32 CSR Report 34 Sales and Marketing Report 36 The Accounts 37 Shareholding Information 58 Share Capital History 59 Mandate for e-Dividend Payment 61 Proxy Form 63 2011 ANNUAL REPORT - LAFARGE CEMENT WAPCO NIGERIA PLC PAGE 1 LAFARGE CEMENT WAPCO NIGERIA PLC L-R: The Country CEO, Lafarge Nigeria and Benin Republic, Mr. Jean-Christophe Barbant; President Goodluck Ebele Jonathan GCFR; Chairman, Board of Directors, Chief Olusegun Osunkeye OFR, OON and Group Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Lafarge Mr. Bruno Lafont at the inauguration of Ewekoro II Plant Lafarge WAPCO: Supporting Nigeria’s Development Lafarge Cement WAPCO Nigeria Plc, a foremost cement manufacturing and marketing company in Nigeria has re-opened a new vista in cement production. A landmark achievement was demonstration of our commitment extract mineral resources from the recorded by Lafarge WAPCO to support the socio-economic earth and transform them into major on December 20, 2011 with the development of the country. construction materials. Our activities inauguration of its state-of-the- meet the basic needs of mankind by art 2.5 metric tonnes brownfield Having fulfilled the national desire to providing materials for housing and cement plant (Lakatabu) in Ewekoro establish a cement manufacturing infrastructures in the country. -

Arokoyo, Bolanle Elizabeth Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

Towards Proto-Niger Congo: Comparison and Reconstruction Paris 18-21 September 2012 A Comparative Phonology of the Olùkùmi, Igala, Owe and Yoruba Languages Arokoyo, Bolanle Elizabeth Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This study presents a comparative analysis of the phonological systems of the Yorùbá, Owé, Igala and Olùkùmi languages with the objective of comparing and finding a reason for their similarities and differences and also proffering a proto form for the languages. These languages belong to the Defoid language family and by default a constituent of Niger Congo language family. Owé along with the other Okun dialects is traditionally regarded as a dialectof Yorùbá. The paper examines what constitutes their similarities and differences that make them to be regarded as different languages. A comparative approach is adopted for the study. Data were collected from native speakers of the languages using the Ibadan Four Hundred Word List of Basic Items. Using discovered common lexemes in the languages, the classification of the languages sound systems and syllable systems are carried out in order to determine the major patterns of differences and similarities. Some major sound changes were discovered in the lexical items of the languages. The systematic substitutions of sounds also constitute another major finding observed in the languages. We have been able to establish in this study that there exists a very strong relationship among these languages, with the discovery of some common lexemes. We, however, discovered that the languages are mutually unintelligible except for Owé that has a degree of mutual intelligibility with Yoruba.