Oercion in Which the Strong Conquers the Weak and Exerts His Position to Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

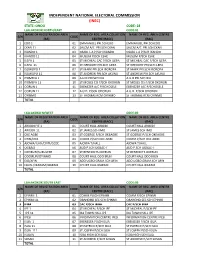

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

A Case of Language Or Dialect Endangerment: Reviving Igbomina Through the Mass Media

US-China Foreign Language, May 2016, Vol. 14, No. 5, 333-339 doi:10.17265/1539-8080/2016.05.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING A Case of Language or Dialect Endangerment: Reviving Igbomina Through the Mass Media Adebukunola A. Atolagbe, Ph.D. Lagos State University, Lagos, Nigeria This paper discusses an attempt to revive and rescue Igbomina, a dialect of Yoruba, from the language shift process evident in many mother tongues spoken in Nigeria. Igbomina is spoken in two local governments in Kwara state, one local government each in Osun and Ekiti states of Nigeria. Two episodes each of a 30 minute programme “Omo Igbomina” on Radio Lagos were critically analyzed to find out if the goals of reviving Igbomina and preventing it from language shift towards the standard Oyo dialect, were being achieved. Many Igbomina youths, ages 15–30, who live outside Igbomina land, can hardly speak Igbomina nor understand it when spoken. A descriptive survey approach to investigate the impact of a peculiar and interesting programme, “Omo Igbomina”, on this class of Igbominas was carried out with the following aims: (1) to discover if the intended audience are aware of the programme and if they are at all interested in such a programme; (2) to evaluate the sociolinguistic worth of the programme; (3) to discover the discourse and pragmatic features of the programme which are peculiarly Igbomina; and (4) to discover the positive effects of the programme or otherwise in revitalizing Igbomina dialect amongst indigenes of Igbomina land, as well as stopping the language shift process from Igbomina dialect to the standard Oyo dialect. -

Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

African Scholar VOL. 18 NO. 6 Publications & ISSN: 2110-2086 Research SEPTEMBER, 2020 International African Scholar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHSS-6) Study of Forms and Functions of Esu – Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Fine and Applied Arts Department, School of Vocational and Technical Education, Tai Solarin College of Education, Omu – Ijebu Abstract The representational images such as pots, rattles, bracelets, stones, cutlasses, wooden combs, staffs, mortals, brooms, etc. are religious and its significance for the worshippers were that they had faith in it. The denominator in the worship of all gods and spirits everywhere is faith. The power of an image was believed to be more real than that of a living being. The Yoruba appear to be satisfied with the gods with whom they are in immediate touch because they believe that when the Orisa have been worshipped, they will transmit what is necessary to Olodumare. This paper examines the traditional practices of the people of Yewa and discovers why Esu is market appellate. It focuses on the classifications of the forms and functions of Esu-Oja representational objects in selected towns in Yewaland. Keywords: appellate, classifications, divinities, fragment, forms, images, libations, mystical powers, Olodumare, representational, sacred, sacrifices, shrine, spirit archetype, transmission and transformation. Introduction Yewa which was formally called there are issues of intra-regional “Egbado” is located on Nigeria’s border conflicts that call for urgent attention. with the Republic of Benin. Yewa claim The popular decision to change the common origin from Ile-Ife, Oyo, ketu, Egbado name according to Asiwaju and Benin. -

Land Accessibility Characteristics Among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria

Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences 2(1): 1-12, 2017; Article no.ARJASS.30086 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Land Accessibility Characteristics among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria Gbenga John Oladehinde 1* , Kehinde Popoola 1, Afolabi Fatusin 2 and Gideon Adeyeni 1 1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out collaboratively by all authors. Author GJO designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors KP and AF supervised the preparation of the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches while author GA led and managed the data analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARJASS/2017/30086 Editor(s): (1) Raffaela Giovagnoli, Pontifical Lateran University, Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano 4, Rome, Italy. (2) Sheying Chen, Social Policy and Administration, Pace University, New York, USA. Reviewers: (1) F. Famuyiwa, University of Lagos, Nigeria. (2) Lusugga Kironde, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17570 Received 16 th October 2016 Accepted 14 th January 2017 Original Research Article st Published 21 January 2017 ABSTRACT Aim: The study investigated challenges of land accessibility among migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. Methodology: Data were obtained through questionnaire administration on a Migrant household head. Multistage sampling technique was used for selection of 161 respondents for the study. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Trends in Owo Traditional Sculptures: 1995 – 2010

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol.5 No.1. December 2015 TRENDS IN OWO TRADITIONAL SCULPTURES: 1995 – 2010 Ebenezer Ayodeji Aseniserare Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] 08034734927, 08057784545 and Efemena I. Ononeme Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] [email protected] 08023112353 Abstract This study probes into the origin, style and patronage of the traditional sculptures in Owo kingdom between 1950 and 2010. It examines comparatively the sculpture of the people and its affinity with Benin and Ife before and during the period in question with a view to predicting the future of the sculptural arts of the people in the next few decades. Investigations of the study rely mainly on both oral and written history, observation, interviews and photographic recordings of visuals, visitations to traditional houses and Owo museum, oral interview of some artists and traditionalists among others. Oral data were also employed through unstructured interviews which bothered on analysis, morphology, formalism, elements and features of the forms, techniques and styles of Owo traditional sculptures, their resemblances and relationship with Benin and Ife artefacts which were traced back to the reigns of both Olowo Ojugbelu 1019 AD to Olowo Oshogboye, the Olowo of Owo between 1600 – 1684 AD, who as a prince, lived and was brought up by the Oba of Benin. He cleverly adopted some of Benin‟s sculptural and historical culture and artefacts including carvings, bronze work, metal work, regalia, bead work, drums and some craftsmen with him on his return to Owo to reign. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

Les Faux Amis Entre Les Langues Igbo Et Yoruba

International Conference on Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences (SHSS-2016) May 24-25, 2016 Paris (France) Les Faux Amis Entre Les Langues Igbo Et Yoruba Dr Kate Ndukauba Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria Abstract: En traduction, les faux amis sont les mots qui, dans des langues différentes, semblent avoir le même sens mais qui en fait, ont des sens différents. Parfois, ils ont la même forme ou des formes identiques, ce qui peut dérouter un traducteur qui ne fait pas bien attention. Il peut y avoir des faux amis entre n’importe qu’elles langues en contact surtout pendant une activité traduisante. Dans cette communication, on compte relever les faux amis entre l’Igbo et le Yoruba, deux langues nigérianes qui appartiennent à la famille des langues dite Niger-Congo. On va parler des deux langues sous étude, discuter les causes des faux amis et les problèmes qui en découlent, et puis suggérer des moyens d’y faire face. Tout cela pour sensibiliser les apprenants et les professeurs des deux langues aussi bien que les traducteurs pour qu’ils fassent bien attention au cours de leur travail pour rester fidèle au sens de ce qui est dit, lu ou traduit. Mots clés: traduction, langue, sens, fidélité, sémantique, orthographe. 1. Introduction Les faux amis constituent un obstacle énorme à une bonne traduction, car le traducteur, s’il ne prend pas garde, peut facilement faire fausse route. Les faux amis se voient entre n’importe quelles langues, qu’elles soient internationales ou locales. Dans cette présentation, on va relever quelques faux amis entre la langue Igbo et la langue Yoruba, deux langues locales nigérianes, dans l’objectif d’attirer l’attention des apprenants des langues et des traducteurs sur l’obstacle pour ne pas se faire piègés. -

Changing Values of Traditional Marriage Among the Awori in Badagry Local Government

International Journal of Social & Management Sciences, Madonna University (IJSMS) Vol.1 No.1, March 2017; pg.131 – 138 CHANGING VALUES OF TRADITIONAL MARRIAGE AMONG THE AWORI IN BADAGRY LOCAL GOVERNMENT OLARINMOYE, ADEYINKA WULEMAT & ALIMI, FUNMILAYO SOFIYAT Department of Sociology, Lagos State University. Email address: [email protected] Abstract Some decades ago, it would have seemed absurd to question the significance of traditional marriage among the Awori-Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria, as it was considered central to the organization of adult life. However, social change has far reaching effects on African traditional life. For instance, the increased social acceptance of pre-marital cohabitation, pre-marital sex and pregnancies and divorce is wide spread among the Yoruba people of today. This however appeared to have replaced the norms of traditional marriage; where marriage is now between two individuals and not families. This research uncovers what marriage values of the Yoruba were and how these values had been influenced overtime. The qualitative method of data collection was used. Data was collected and analyzed utilizing the content analysis and ethnographic summary techniques. The study revealed that modernization, education, mixture of cultures and languages, inter-marriage and electronic media have brought about changes in traditional marriage, along with consequences such as; drop in family standard, marriage instability, weak patriarchy system, and of values and customs. Despite the social changes, marriage remains significant value for individuals, families and in Yoruba society as a whole. Keywords: Traditional values, marriage, social change, Yoruba. INTRODUCTION The practice of marriage is apparently one of the most interesting aspects of human culture. -

Oral Performance of Ìrègún Music in Yagbaland, Kogi State, Nigeria: an Overview

ORAL PERFORMANCE OF ÌRÈGÚN MUSIC IN YAGBALAND, KOGI STATE, NIGERIA: AN OVERVIEW Stephen Olusegun Titus, Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria. Abstract Performance is one of the major arts in most African countries. Among the Yoruba in Nigeria several genre of oral performance has been researched and documented. These include the ijala, iwi, oriki ekun iyawo, Iyere Ifa, iwure, among others. However, very little attention and studies have been committed to oral performance of Ìrègún chants and songs in Yagbaland. This paper, therefore, focuses on the evaluation of oral performance of Ìrègún chants and songs among Yagba people in Kogi State, located in North central of Nigeria. Primary data were collected through 3 In-depth and 3 Key Informant interviews of leaders and members of Ìrègún musical groups. In addition to 3 Participant Observation and 3 Non-Participant Observation meth- ods from Yagba-West, Yagba-East and Mopamuro Local Government Areas of Kogi State, music recordings, photographs of Ìrègún performances, and 6 chants were purposefully sampled. Secondary data were collected through library, archival and Internet sources. Although closely interwoven, Ìrègún performance is structured into preparation, actual and post-performance activities. While chanting, singing, playing of musical instruments and dancing forms the performance dimensions. Ire- gun music serves as veritable mirror and cultural preserver in Yagba communities. Keywords: Iregun Music; Performance; Yagbaland; Chants and Songs Epiphany: Journal of Transdisciplinary Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, (2015) © Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences 9 S.O. Titus Introduction Performance of oral genre varies in Yoruba culture as varied as contexts for per- formance. In essence, oral performance can only be realized when it is actually performed.