Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

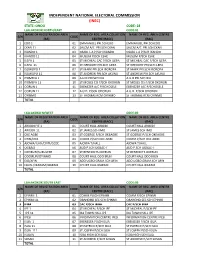

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

Dr. Sanya Onabamiro – Copepods - Biology/Ecology – Guineaworm Transmission Copepods Identified & Characterised by Dr

Tropical Diseases in Africa Four Phases • Devastation • Discovery • Development • Deployment Pre-colonial & early colonial era Deaths of Europeans in West Africa Expedition Year Europeans Deaths Mungo Park 1805 44 39 Tuckey 1816 44 21 Clapperton 1825-7 5 4 MacGregor-Laird 1832-4 41 32 Trotter 1841 145 42 Take care and beware of the Bight of Benin For few come out, though many go in Arab African Mixed Meningitis in Africa Meningitis Belt Countries >15 cases per 100,000 population Seasonal Epidemics in Meningitis Belt Discovery •Trypanosomiasis •Yellow Fever •Malaria •Kwashiokhor Trypanosomiasis Milestones • 1902 Ford and Dutton, identified Trypanosoma brucei gambiense . • 1903 Castellani in Uganda parasite in CSF • 1903 David Bruce –tsetse fly as the vector • 1906 Ayres Kopke - arsenic drug, Atoxyl. • 1924 Tryparsamide less toxic than Atoxyl, • 1932 Atoxyl blinded 700 patients became Friedheim developed melarsoprol Numerous Tsetse Flies Yellow Fever Americas • Finlay – mosquito transmission • Walter Reed – viral agent, extrinsic incubation period in Aedes Aegypti Africa • Noguchi - Accra • Stokes - Lagos Live vaccine developed Tools for Disease Control Few remedies until mid-20th century • Salvarsan - syphilis • Antrypol -trypanosomiasis, onchocersiasis), • Pamaquine, chloroquine, primaquine, and pyrimethamine - malaria • Penicillin - yaws • Dapsone - leprosy Colonial Health Research • Expeditions • Colonial Medical Services • Research Institutes • Schools of Tropical Medicine in Europe • International Research Institutes European Scientists in Africa Outstanding world class scientists • Robert Koch • Aldo Castellani • George MacDonald Dr. Cecily Williams Jamaican, 1893-1992 1923 Graduated in Medicine, …Oxford University 1929-36 Served in Gold Coast Learnt Twi Identified Kwashiokhor 1936- Worked in 58 countries 1941-45 Prisoner of war “Health Education is listening to the people” Major C. -

Bascom Collection

William Russell Bascom Collection A survey of the documentation of the William Russell Bascom Collection at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley January 2019 Prepared by Lucy Portnoff, Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program with contributions by Delphine Sims, History of Art Graduate Student and update by Ira Jacknis and Linda Waterfield 1. Biographical Material, p.1 2. Publications, p.3 3. Summary of the Hearst Museum Accession Files and Permanent Collections, p.4 4. Summary of Material in the Hearst Museum Archive, p.7 5. Summary of Media Collection at the Hearst Museum, p.16 1. Biographical Material Relevant to Bascom William Russell Bascom was born on May 23, 1912 in Princeton, Illinois, and died on September 11, 1981 in San Francisco, California. Bascom received his B.A.in 1933 from the University of Wisconsin (Physics), his M.A. in 1936 from the University of Wisconsin (Anthropology), and his Ph.D. in 1939 from Northwestern University (Anthropology). Bascom specialized in the art and culture of West Africa and the African Diaspora, and is especially known for his studies of Nigerian Yoruba culture and religion. In 1954, Bascom crafted the “four functions of folklore.” He was the Director of the Robert H. Lowie Museum (present-day Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology) at the University of California, Berkeley from 1957 to 1979. Further biographical information can be found on the Online Archive of California Finding Aid to the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley:http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5p3035gz/ Index of Biographical Material at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley: William R. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

A Review of African Initiated Churches and Their Contributions to the Development of Education in Nigeria

International Journal of African and Asian Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2409-6938 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.15, 2015 A Review of African Initiated Churches and Their Contributions to the Development of Education in Nigeria Dr Tiwatola Abidemi Falaye Department of Religious Studies, Faculty of Arts, Olabisi Onabanjo University, PMB 2002, Ago Iwoye, Ogun State , Nigeria. Abstract The paper reflects the opinion of scholars on African initiated churches. The contributions of African independent churches to the development of education in Nigeria were also highlighted. The factors that influenced the rise of these Churches, distinguishing features and characteristic of these churches were also dealt with in the paper. Finally, the initial problems of the AIC'S which includes low level of education was addressed in the paper. The church rose up to the challenges by establishing schools, theological colleges and training centre to solve the problem of low level of education. In this way the churches contributed a lot into the development of Education in Nigeria. Introduction The contributions of the African Independent Churches to the development of Education in Nigeria cannot be over emphasized. Some of these AICS are, Church of the Lord Aladura (COLA), The Cherubim and Seraphim, The Christ Apostolic Church, the Celestial Church of Christ and the Zionist Church. These Churches have established Schools and employed teachers ranging from. Primary Schools, to Secondary Schools, teacher training colleges and colleges of education. To crown it all many of these Churches have founded Universities spending huge amounts ranging to millions of naira to keep these institutions going. -

A Case of Language Or Dialect Endangerment: Reviving Igbomina Through the Mass Media

US-China Foreign Language, May 2016, Vol. 14, No. 5, 333-339 doi:10.17265/1539-8080/2016.05.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING A Case of Language or Dialect Endangerment: Reviving Igbomina Through the Mass Media Adebukunola A. Atolagbe, Ph.D. Lagos State University, Lagos, Nigeria This paper discusses an attempt to revive and rescue Igbomina, a dialect of Yoruba, from the language shift process evident in many mother tongues spoken in Nigeria. Igbomina is spoken in two local governments in Kwara state, one local government each in Osun and Ekiti states of Nigeria. Two episodes each of a 30 minute programme “Omo Igbomina” on Radio Lagos were critically analyzed to find out if the goals of reviving Igbomina and preventing it from language shift towards the standard Oyo dialect, were being achieved. Many Igbomina youths, ages 15–30, who live outside Igbomina land, can hardly speak Igbomina nor understand it when spoken. A descriptive survey approach to investigate the impact of a peculiar and interesting programme, “Omo Igbomina”, on this class of Igbominas was carried out with the following aims: (1) to discover if the intended audience are aware of the programme and if they are at all interested in such a programme; (2) to evaluate the sociolinguistic worth of the programme; (3) to discover the discourse and pragmatic features of the programme which are peculiarly Igbomina; and (4) to discover the positive effects of the programme or otherwise in revitalizing Igbomina dialect amongst indigenes of Igbomina land, as well as stopping the language shift process from Igbomina dialect to the standard Oyo dialect. -

Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

African Scholar VOL. 18 NO. 6 Publications & ISSN: 2110-2086 Research SEPTEMBER, 2020 International African Scholar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHSS-6) Study of Forms and Functions of Esu – Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Fine and Applied Arts Department, School of Vocational and Technical Education, Tai Solarin College of Education, Omu – Ijebu Abstract The representational images such as pots, rattles, bracelets, stones, cutlasses, wooden combs, staffs, mortals, brooms, etc. are religious and its significance for the worshippers were that they had faith in it. The denominator in the worship of all gods and spirits everywhere is faith. The power of an image was believed to be more real than that of a living being. The Yoruba appear to be satisfied with the gods with whom they are in immediate touch because they believe that when the Orisa have been worshipped, they will transmit what is necessary to Olodumare. This paper examines the traditional practices of the people of Yewa and discovers why Esu is market appellate. It focuses on the classifications of the forms and functions of Esu-Oja representational objects in selected towns in Yewaland. Keywords: appellate, classifications, divinities, fragment, forms, images, libations, mystical powers, Olodumare, representational, sacred, sacrifices, shrine, spirit archetype, transmission and transformation. Introduction Yewa which was formally called there are issues of intra-regional “Egbado” is located on Nigeria’s border conflicts that call for urgent attention. with the Republic of Benin. Yewa claim The popular decision to change the common origin from Ile-Ife, Oyo, ketu, Egbado name according to Asiwaju and Benin. -

Land Accessibility Characteristics Among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria

Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences 2(1): 1-12, 2017; Article no.ARJASS.30086 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Land Accessibility Characteristics among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria Gbenga John Oladehinde 1* , Kehinde Popoola 1, Afolabi Fatusin 2 and Gideon Adeyeni 1 1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out collaboratively by all authors. Author GJO designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors KP and AF supervised the preparation of the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches while author GA led and managed the data analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARJASS/2017/30086 Editor(s): (1) Raffaela Giovagnoli, Pontifical Lateran University, Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano 4, Rome, Italy. (2) Sheying Chen, Social Policy and Administration, Pace University, New York, USA. Reviewers: (1) F. Famuyiwa, University of Lagos, Nigeria. (2) Lusugga Kironde, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17570 Received 16 th October 2016 Accepted 14 th January 2017 Original Research Article st Published 21 January 2017 ABSTRACT Aim: The study investigated challenges of land accessibility among migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. Methodology: Data were obtained through questionnaire administration on a Migrant household head. Multistage sampling technique was used for selection of 161 respondents for the study. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Trends in Owo Traditional Sculptures: 1995 – 2010

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol.5 No.1. December 2015 TRENDS IN OWO TRADITIONAL SCULPTURES: 1995 – 2010 Ebenezer Ayodeji Aseniserare Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] 08034734927, 08057784545 and Efemena I. Ononeme Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] [email protected] 08023112353 Abstract This study probes into the origin, style and patronage of the traditional sculptures in Owo kingdom between 1950 and 2010. It examines comparatively the sculpture of the people and its affinity with Benin and Ife before and during the period in question with a view to predicting the future of the sculptural arts of the people in the next few decades. Investigations of the study rely mainly on both oral and written history, observation, interviews and photographic recordings of visuals, visitations to traditional houses and Owo museum, oral interview of some artists and traditionalists among others. Oral data were also employed through unstructured interviews which bothered on analysis, morphology, formalism, elements and features of the forms, techniques and styles of Owo traditional sculptures, their resemblances and relationship with Benin and Ife artefacts which were traced back to the reigns of both Olowo Ojugbelu 1019 AD to Olowo Oshogboye, the Olowo of Owo between 1600 – 1684 AD, who as a prince, lived and was brought up by the Oba of Benin. He cleverly adopted some of Benin‟s sculptural and historical culture and artefacts including carvings, bronze work, metal work, regalia, bead work, drums and some craftsmen with him on his return to Owo to reign.