BUCCINATOR MYOMUCOSAL FLAP Johan Fagan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Branches of the Maxillary Artery of the Domestic

Table 4.2: Branches of the Maxillary Artery of the Domestic Pig, Sus scrofa Artery Origin Course Distribution Departs superficial aspect of MA immediately distal to the caudal auricular. Course is typical, with a conserved branching pattern for major distributing tributaries: the Facial and masseteric regions via Superficial masseteric and transverse facial arteries originate low in the the masseteric and transverse facial MA Temporal Artery course of the STA. The remainder of the vessel is straight and arteries; temporalis muscle; largely unbranching-- most of the smaller rami are anterior auricle. concentrated in the proximal portion of the vessel. The STA terminates in the anterior wall of the auricle. Originates from the lateral surface of the proximal STA posterior to the condylar process. Hooks around mandibular Transverse Facial Parotid gland, caudal border of the STA ramus and parotid gland to distribute across the masseter Artery masseter muscle. muscle. Relative to the TFA of Camelids, the suid TFA has a truncated distribution. From ventral surface of MA, numerous pterygoid branches Pterygoid Branches MA Pterygoideus muscles. supply medial and lateral pterygoideus muscles. Caudal Deep MA Arises from superior surface of MA; gives off masseteric a. Deep surface of temporalis muscle. Temporal Artery Short course deep to zygomatic arch. Contacts the deep Caudal Deep Deep surface of the masseteric Masseteric Artery surface of the masseter between the coronoid and condylar Temporal Artery muscle. processes of the mandible. Artery Origin Course Distribution Compensates for distribution of facial artery. It should be noted that One of the larger tributaries of the MA. Originates in the this vessel does not terminate as sphenopalatine fossa as almost a terminal bifurcation of the mandibular and maxillary labial MA; lateral branch continuing as buccal and medial branch arteries. -

Gross Anatomy

www.BookOfLinks.com THE BIG PICTURE GROSS ANATOMY www.BookOfLinks.com Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the infor- mation contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the product information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. www.BookOfLinks.com THE BIG PICTURE GROSS ANATOMY David A. Morton, PhD Associate Professor Anatomy Director Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy University of Utah School of Medicine Salt Lake City, Utah K. Bo Foreman, PhD, PT Assistant Professor Anatomy Director University of Utah College of Health Salt Lake City, Utah Kurt H. -

Head & Neck Surgery Course

Head & Neck Surgery Course Parapharyngeal space: surgical anatomy Dr Pierfrancesco PELLICCIA Pr Benjamin LALLEMANT Service ORL et CMF CHU de Nîmes CH de Arles Introduction • Potential deep neck space • Shaped as an inverted pyramid • Base of the pyramid: skull base • Apex of the pyramid: greater cornu of the hyoid bone Introduction • 2 compartments – Prestyloid – Poststyloid Anatomy: boundaries • Superior: small portion of temporal bone • Inferior: junction of the posterior belly of the digastric and the hyoid bone Anatomy: boundaries Anatomy: boundaries • Posterior: deep fascia and paravertebral muscle • Anterior: pterygomandibular raphe and medial pterygoid muscle fascia Anatomy: boundaries • Medial: pharynx (pharyngobasilar fascia, pharyngeal wall, buccopharyngeal fascia) • Lateral: superficial layer of deep fascia • Medial pterygoid muscle fascia • Mandibular ramus • Retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland • Posterior belly of digastric muscle • 2 ligaments – Sphenomandibular ligament – Stylomandibular ligament Aponeurosis and ligaments Aponeurosis and ligaments • Stylopharyngeal aponeurosis: separates parapharyngeal spaces to two compartments: – Prestyloid – Poststyloid • Cloison sagittale: separates parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal space Aponeurosis and ligaments Stylopharyngeal aponeurosis Muscles stylohyoidien Stylopharyngeal , And styloglossus muscles Prestyloid compartment Contents: – Retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland – Minor or ectopic salivary gland – CN V branch to tensor -

Adipose Stem Cells from Buccal Fat Pad and Abdominal Adipose Tissue for Bone Tissue Engineering

Adipose Stem Cells from Buccal Fat Pad and Abdominal Adipose Tissue for Bone tissue Engineering Elisabet Farré Guasch Dipòsit Legal: B-25086-2011 ISBN: 978-90-5335-394-3 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/31987 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). -

The Facial Artery of the Dog

Oka jimas Folia Anat. Jpn., 57(1) : 55-78, May 1980 The Facial Artery of the Dog By MOTOTSUNA IRIFUNE Department of Anatomy, Osaka Dental University, Osaka (Director: Prof. Y. Ohta) (with one textfigure and thirty-one figures in five plates) -Received for Publication, November 10, 1979- Key words: Facial artery, Dog, Plastic injection, Floor of the mouth. Summary. The course, branching and distribution territories of the facial artery of the dog were studied by the acryl plastic injection method. In general, the facial artery was found to arise from the external carotid between the points of origin of the lingual and posterior auricular arteries. It ran anteriorly above the digastric muscle and gave rise to the styloglossal, the submandibular glandular and the ptery- goid branches. The artery continued anterolaterally giving off the digastric, the inferior masseteric and the cutaneous branches. It came to the face after sending off the submental artery, which passed anteromedially, giving off the digastric and mylohyoid branches, on the medial surface of the mandible, and gave rise to the sublingual artery. The gingival, the genioglossal and sublingual plical branches arose from the vessel, while the submental artery gave off the geniohyoid branches. Posterior to the mandibular symphysis, various communications termed the sublingual arterial loop, were formed between the submental and the sublingual of both sides. They could be grouped into ten types. In the face, the facial artery gave rise to the mandibular marginal, the anterior masseteric, the inferior labial and the buccal branches, as well as the branch to the superior, and turned to the superior labial artery. -

Deep Neck Infections 55

Deep Neck Infections 55 Behrad B. Aynehchi Gady Har-El Deep neck space infections (DNSIs) are a relatively penetrating trauma, surgical instrument trauma, spread infrequent entity in the postpenicillin era. Their occur- from superfi cial infections, necrotic malignant nodes, rence, however, poses considerable challenges in diagnosis mastoiditis with resultant Bezold abscess, and unknown and treatment and they may result in potentially serious causes (3–5). In inner cities, where intravenous drug or even fatal complications in the absence of timely rec- abuse (IVDA) is more common, there is a higher preva- ognition. The advent of antibiotics has led to a continu- lence of infections of the jugular vein and carotid sheath ing evolution in etiology, presentation, clinical course, and from contaminated needles (6–8). The emerging practice antimicrobial resistance patterns. These trends combined of “shotgunning” crack cocaine has been associated with with the complex anatomy of the head and neck under- retropharyngeal abscesses as well (9). These purulent col- score the importance of clinical suspicion and thorough lections from direct inoculation, however, seem to have a diagnostic evaluation. Proper management of a recog- more benign clinical course compared to those spreading nized DNSI begins with securing the airway. Despite recent from infl amed tissue (10). Congenital anomalies includ- advances in imaging and conservative medical manage- ing thyroglossal duct cysts and branchial cleft anomalies ment, surgical drainage remains a mainstay in the treat- must also be considered, particularly in cases where no ment in many cases. apparent source can be readily identifi ed. Regardless of the etiology, infection and infl ammation can spread through- Q1 ETIOLOGY out the various regions via arteries, veins, lymphatics, or direct extension along fascial planes. -

The Buccal Fat Pad: Importance and Function

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 15, Issue 6 Ver. XIII (June. 2016), PP 79-81 www.iosrjournals.org The Buccal Fat Pad: Importance And Function Ulduz Zamani Ahari1, Hosein Eslami2, Parisa Falsafi*2, Aila Bahramian2, Saleh Maleki1 1. Post Graduate Student Of Oral Medicine, Dental Faculty, Tabriz University Of Medical Science, Tabriz, Iran. 2.Department Of Oral Medicine, Dental Faculty, Tabriz University Of Medical Science, Tabriz, Iran. ●Corresponding Author Email:[email protected] Abstract: The buccal fat is an important anatomic structure intimately related to the masticatory muscles, facial nerve , and parotid duct.while anatomically complex , an understanding of its boundaries will allow the surgeon to safely manipulate this structure in reconstructive and aesthetic procedures . Technically, the buccal fat pad is easily accessed and moblized . It is does not cause any noticeable defect in the cheek or mouth, and it can be performed in a very short time and without causing complication for the patient. The pedicled BFP graft is more resistant to infection than other kinds of free graft and will result in very success. The buccal fat pad has a satisfactory vascular supply , This property of graft and other properties will allow for the closure of defects that cannot be repaired by conventional procedures. The buccal fat pad exposed through an intraoral and buccal incision , has several clinical application including aesthetic improvement , close of oroantral and Oroantral defects reconstruction of surgical defects and palatal cleft defects and palatal cleft defects , reconstruction of maxilla and palatal defects. -

Computed Tomography of the Buccomasseteric Region: 1

605 Computed Tomography of the Buccomasseteric Region: 1. Anatomy Ira F. Braun 1 The differential diagnosis to consider in a patient presenting with a buccomasseteric James C. Hoffman, Jr. 1 region mass is rather lengthy. Precise preoperative localization of the mass and a determination of its extent and, it is hoped, histology will provide a most useful guide to the head and neck surgeon operating in this anatomically complex region. Part 1 of this article describes the computed tomographic anatomy of this region, while part 2 discusses pathologic changes. The clinical value of computed tomography as an imaging method for this region is emphasized. The differential diagnosis to consider in a patient with a mass in the buccomas seteric region, which may either be developmental, inflammatory, or neoplastic, comprises a rather lengthy list. The anatomic complexity of this region, defined arbitrarily by the soft tissue and bony structures including and surrounding the masseter muscle, excluding the parotid gland, makes the accurate anatomic diagnosis of masses in this region imperative if severe functional and cosmetic defects or even death are to be avoided during treatment. An initial crucial clinical pathoanatomic distinction is to classify the mass as extra- or intraparotid. Batsakis [1] recommends that every mass localized to the cheek region be considered a parotid tumor until proven otherwise. Precise clinical localization, however, is often exceedingly difficult. Obviously, further diagnosis and subsequent therapy is greatly facilitated once this differentiation is made. Computed tomography (CT), with its superior spatial and contrast resolution, has been shown to be an effective imaging method for the evaluation of disorders of the head and neck. -

Dynamic Manoeuvres on MRI in Oral Cancers – a Pictorial Essay Diva Shah HCG Cancer Centre, Sola Science City Road, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

Published online: 2021-07-19 HEAD AND NECK IMAGING Dynamic manoeuvres on MRI in oral cancers – A pictorial essay Diva Shah HCG Cancer Centre, Sola Science City Road, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India Correspondence: Dr. Diva Shah, HCG Cancer Centre, Sola Science City Road, Ahmedabad ‑ 380060, Gujarat, India. E‑mail: [email protected] Abstract Magnetic resonance imaging has been shown to be a useful tool in the evaluation of oral malignancies because of direct visualization of lesions due to high soft tissue contrast and multiplanar capability. However, small oral cavity tumours pose an imaging challenge due to apposed mucosal surfaces of oral cavity, metallic denture artefacts and submucosal fibrosis. The purpose of this pictorial essay is to show the benefits of pre and post contrast MRI sequences using various dynamic manoeuvres that serve as key sequences in the evaluation of various small oral (buccal mucosa and tongue as well as hard/soft palate) lesions for studying their extent as well as their true anatomic relationship. Key words: Dynamic manoeuvres; MRI; oral cavity lesions Introduction oral cavity lesions particularly in patients with sub‑mucosal fibrosis, RMT lesions, post‑operative evaluation and in In the imaging of oral cavity lesions, it is important presence of metallic dental streak artefacts. MRI in these to determine precisely the site of tumour origin, size, circumstances scores over MDCT and is a preferred modality trans‑spatial extension and invasion of deep structures.[1] with excellent soft tissue contrast resolution. Evaluation of small tumours of the oral cavity is always a diagnostic challenge for both the head and neck surgeon MR imaging with various dynamic manoeuvres provides and the head and neck radiologist. -

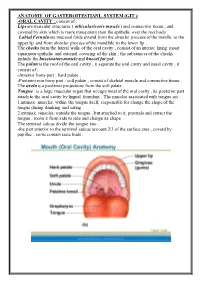

ANATOMY of GASTEROITESTIANL SYSTEM (GIT ): Consist of : ORAL CAVITY

ANATOMY OF GASTEROITESTIANL SYSTEM (GIT ): -ORAL CAVITY : consist of : Lips are muscular structures ( orbicularis oris muscle ) and connective tissue , and covered by skin which is more transparent than the epithelia over the rest body . Labial Fernula are mucosal folds extend from the alveolar process of the maxilla to the upper lip and from alveolar process of the mandible to the lower lip . The cheeks form the lateral walls of the oral cavity , consist of an interior lining moist squamous epithelia and external covering of the skin , the substances of the cheeks include the buccinators muscle and buccal fat pad. The palate is the roof of the oral cavity , it separate the oral cavity and nasal cavity , it consist of : -Anterior bony part : hard palate . -Posterior non bony part : soft palate , consist of skeletal muscle and connective tissue . The uvela is a posterior projections from the soft palate . Tongue : is a large muscular organ that occupy most of the oral cavity , its posterior part attach to the oral cavity by lingual frenulum . The muscles associated with tongue are : 1.intrinsic muscles: within the tongue itself, responsible for change the shape of the tongue during drinking and eating . 2.extrinsic muscles: outside the tongue , but attached to it, protrude and retract the tongue , move it from side to side and change its shape . The terminal sulcus divide the tongue into : -the part anterior to the terminal sulcus account 2/3 of the surface area , coverd by papillae , some contain taste buds . -the posterior one third is devoid of papillae , has few scattered taste buds , it has few small glands and lymphatic tissue (lingual tissue ) Teeth : adults have 32 teeth distributed in two dental arches, the maxillary arch , and the mandibular arch . -

The Structure and Movement of Clarinet Playing D.M.A

The Structure and Movement of Clarinet Playing D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sheri Lynn Rolf, M.D. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Chair Dr. David Hedgecoth Professor Katherine Borst Jones Dr. Scott McCoy Copyrighted by Sheri Lynn Rolf, M.D. 2018 Abstract The clarinet is a complex instrument that blends wood, metal, and air to create some of the world’s most beautiful sounds. Its most intricate component, however, is the human who is playing it. While the clarinet has 24 tone holes and 17 or 18 keys, the human body has 205 bones, around 700 muscles, and nearly 45 miles of nerves. A seemingly endless number of exercises and etudes are available to improve technique, but almost no one comments on how to best use the body in order to utilize these studies to maximum effect while preventing injury. The purpose of this study is to elucidate the interactions of the clarinet with the body of the person playing it. Emphasis will be placed upon the musculoskeletal system, recognizing that playing the clarinet is an activity that ultimately involves the entire body. Aspects of the skeletal system as they relate to playing the clarinet will be described, beginning with the axial skeleton. The extremities and their musculoskeletal relationships to the clarinet will then be discussed. The muscles responsible for the fine coordinated movements required for successful performance on the clarinet will be described. -

18612-Oropharynx Dr. Teresa Nunes.Pdf

European Course in Head and Neck Neuroradiology Disclosures 1st Cycle – Module 2 25th to 27th March 2021 No conflict of interest regarding this presentation. Oropharynx Anatomy and Pathologies Teresa Nunes Hospital Garcia de Orta, Hospital Beatriz Ângelo Portugal Oropharynx: Anatomy and Pathologies Oropharynx: Anatomy Objectives Nasopharynx • Review the anatomy of the oropharynx (subsites, borders, surrounding spaces) Oropharynx • Become familiar with patterns of spread of oropharyngeal infections and tumors Hypopharynx • Highlight relevant imaging findings for accurate staging and treatment planning of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma Oropharynx: Surrounding Spaces Oropharynx: Borders Anteriorly Oral cavity Superior Soft palate Laterally Parapharyngeal space Anterior Circumvallate papillae Masticator space Anterior tonsillar pillars Posteriorly Retropharyngeal space Posterior Posterior pharyngeal wall Lateral Anterior tonsillar pillars Tonsillar fossa Posterior tonsillar pillars Inferior Vallecula Oropharynx: Borders Oropharynx: Borders Oropharyngeal isthmus Superior Soft palate Anterior Circumvallate papillae Anterior 2/3 vs posterior 1/3 of tongue Anterior tonsillar pillars Palatoglossal arch Inferior Vallecula Anterior tonsillar pillar: most common Pre-epiglottic space Glossopiglottic fold (median) location of oropharyngeal squamous Can not be assessed clinically Pharyngoepiglottic folds (lateral) Invasion requires supraglottic laryngectomy !cell carcinoma ! Oropharynx: Borders Muscles of the Pharyngeal Wall Posterior pharyngeal