Volume 39, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

~. ~. ~••r __._ .,'__, __----., The National Ubrary supplies copies of this article under licence from the Copyright Agency Limited (GAL). Further reproductions of this' article can only be made under licence. ·111111111111 200003177 . J The Last Man: The mutilation ofWilliam Lanne in 1869 and its aftermath Stefan Petrow Regarding the story of King Billy's Head, there are so many versions of it that it might be as well if you sent rhe correct details.! In 1869 William Lanne, the last 'full-blooded' Tasmanian Aboriginal male, died.2 Lying in the Hobart Town General Hospital, his dead body was mutilated by scientists com peting for the right to secure the skeleton. The first mutilation by Dr. William Lodewyk Crowther removed Lanne's head. The second mutilation by Dr. George Stokell and oth ers removed Lanne's hands and feet. After Lanne's burial, Stokell and his colleagues removed Lanne's body from his grave before Crowther and his party could do the same. Lanne's skull and body were never reunited. They were guarded jealously by the respective mutilators in the interests of science. By donating Lanne's skeleton, Crowther wanted to curry favour with the prestigious Royal College of Surgeons in London, while Stokell, anxious to retain his position as house-surgeon at the general hospital, wanted to cultivate good relations with the powerful men associated with the Royal Society of Tasmania. But, perhaps because of the scandal associated with the mutilation, no scientific study of Lanne's skull or skeleton was ever published or, as far as we know, even attempted. -

Alexandros Stogiannos Dismissing the Myth of the Ratzelian

Historical Geography and Geosciences Alexandros Stogiannos The Genesis of Geopolitics and Friedrich Ratzel Dismissing the Myth of the Ratzelian Geodeterminism Historical Geography and Geosciences This book series serves as a broad platform for contributions in the field of Historical Geography and related Geoscience areas. The series welcomes proposals on the history and dynamics of place and space and their influence on past, present and future geographies including historical GIS, cartography and mapping, climatology, climate history, meteorology and atmospheric sciences, environmental geography, hydrology, geology, oceanography, water management, instrumentation, geographical traditions, historical geography of urban areas, settlements and landscapes, historical regional studies, history of geography and historic geographers and geoscientists among other topically related areas and other interdisciplinary approaches. Contributions on past (extreme) weather events or natural disasters including regional and global reanalysis studies also fit into the series. Publishing a broad portfolio of peer-reviewed scientific books Historical Geography and Geosciences contains research monographs, edited volumes, advanced and undergraduate level textbooks, as well as conference proceedings. This series appeals to scientists, practitioners and students in the fields of geography and history as well as related disciplines, with exceptional titles that are attractive to a popular science audience. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15611 -

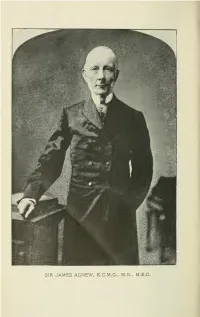

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©Bititarn*

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©bititarn* Sir James Wilson Agnew, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C., Senior Vice-President of the Royal Society of Tas- mania. Died on cSth November, 1901, in the 87th year of his age. —Born at Ballyclare, Ireland, on the 2nd October, 1815, he studied for the medical profession in London and Paris, and at Glas^^-ow, where he graduated M.D., as his father and grandfather had done before him, and came to Australia in 1839. After a short stay in New South Wales and Victoria (then known as Port Phillip), he accepted from Sir John Franklin the offer of appointment as medical officer to an important station at Tasman's Peninsula, wliere he devoted the greater part of his leisure time to the study of natural history. Prior to his removal to Hobart for the more extended practice of his profession, in which he sub- sequently attained a position of acknowledged eminence, he had assisted in founding the Tasmanian Societ}^, and lie became an active member of the Royal Society, into which the former Society merged in 1844. Shortly after the retirement of Dr. Milligan, its Secretary and Curator, in 1860, he undertook the duties of Seci'etary as a labour of love, in order that the whole of the limited amount available out of income might be appropriated as salary for the Curator of the Museum. From that time on- wards, except during occasional periods of absence from Tasmania, he continued to act as chief executive officer of the Royal Society in the capacity of Honorary Secretary for many years, and latterly in that of Chairman of the Council ; and to the admirable manner in which those self-imposed duties were discharo-ed. -

Development of Tasmanian Water Right Legislation 1877-1885: a Tortuous Process

Journal of Australasian Mining History, Vol. 15, 2017 Development of Tasmanian water right legislation 1877-1885: a tortuous process By KEITH PRESTON rior to the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, a right to water was governed by the riparian doctrine, a common law principle of entitlement that was established P in Great Britain during the 15th and 16th centuries.1 Water entitlements were tied to land ownership whereby the occupant could access a watercourse flowing through a landholding or along its boundary. This doctrine was introduced to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land in 1828 with the passing of the Australian Courts Act (9 Geo. No. 4) that transferred ‘all laws and statutes in force in the realm of England’.2 The riparian doctrine became part of New South Wales common law following a Supreme Court ruling in 1859.3 During the Californian and Victorian gold rushes, the principle of prior appropriation was established to protect the rights of mining leaseholders on crown land but riparian rights were retained for other users, particularly for irrigation of private land. The principle of prior appropriation was based on first possession, which established priority when later users obtained water from a common source, although these rights could be traded and were a valuable asset in the regulation of water supply to competing claims on mining fields.4 In Tasmania, disputes over water rights between 1881-85 challenged the application of these two doctrines, forcing repeated revision of legislation. The Tasmanian Parliament passed the first gold mining legislation in September 1859, eight years after the first gold rushes in Victoria and New South Wales, which marked the widespread introduction of alluvial mining in Australia. -

Masters of Political Studies Faculty of Humanities Jews As the Universal Enemy: an Analysis of Social Darwinism As the Driving

Masters of Political Studies Faculty of Humanities Jews as the Universal Enemy: An analysis of Social Darwinism as the driving force behind the Holocaust. Candidate: Sasha Edel Supervisor: Professor Joel Quirk Date of Submission: 15 March 2017 Word Count: 22,702 A research report submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Political Studies. Table of Contents Plagiarism Declaration 3 Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 Introduction 7 Chapter One 13 (1.1) Darwin’s Theory of Evolution 14 (1.2) Darwinism on Society 16 (1.3) Hitler’s Darwinism and Nazi Germany 19 Chapter Two 25 (2.1) The Rise of Totalitarianism 26 (2.2) The Role of the Egocratic Leader 29 (2.3) Manufacturing the Other 32 Chapter Three 37 (3.1) Hitler’s Master Race 38 (3.2) Jew Hatred 42 (3.3) The Judeo-Bolshevik Myth 46 Chapter Four 51 (4.1) Lebensraum 52 (4.2) Statelessness and Conquest 55 (4.3) The Extermination of Six Million Jews 60 Conclusion 64 Bibliography 71 2 University of the Witwatersrand School of Political Studies PLAGIARISM POLICY Declaration by Students I ___________________________ (Student number: _________________) am a student registered for ______________________ in the year __________. I hereby declare the following: • I am aware that plagiarism (the use of someone else’s work without their permission and/or without acknowledging the original source) is wrong. • I confirm that ALL the work submitted for assessment for the above course is my own unaided work except where I have explicitly indicated otherwise. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

Clonal Sncittn oi Casmanhi. ABSTRACT OF PHOCEELINaS, APPwIL 29th, 1902. A meeting of the Eoyal Socie!;y of Tas- and expansive beyond any limit they mania was held on Tuesday evening, April could assign to it.'" The Fellows had 29, 1902, in the society^s new room, Argyle- done very well so far. They had got s'treet. The President, His Excellency natural history specimens, and a fairly the GrOTernor, Sir Arthur Havelook, good rep.resantation of art, and, on tlie G.C.S.I., G.'C.M.G., presided. The Go- whole, he thought the institution would vernor was accompanied by Lady Have- compare favourably with any institution lock and Captain Gaskell, A.D.C. in the other States. But they could say now. as the secretary said in 18o7, that the Welcome to the New President. society must be cumulative and expan- sive beyond any limit thsy could a».-ign The Hon. Nicholas J. Brown, Speaker to it. Its first expansion now should be of the House of Assembly, and Vice-Presi- in the direction of the securing and equip- dent of the Eoyal Society, said he was ment of a Techuological museum. I'hat charged with a duty of a y&i:y pleasant seemed to be necessary, in view of the an- character. He had, on behalf of the ticipations that, in the near fature, Tas- Fellows of the Eoyal Society, to welcome mania would become an important manu- His Excellency on that, the first, occasion facturing and distributing centre for the of fTiS presiding at a meeting of the Eel- whole of Australia. -

Melbourne Club Address 12Th Aug 09

J Michael M Youl The success of his experiment may have been the TASMANIAN Club address 6 July 2012 fore runner to storing animal and human semen and storing animal and human fertile eggs, IVF and so Good evening Gentlemen on [now I’m really out of my depth]. In the 1850’s and 60’s there was a strong desire by Packaging took a great deal of sorting out. James colonist in Tasmania and Victoria to introduce Youl spent 10 years to find the right mix. His Atlantic salmon [ salmo salar ] to our beautiful experiments to retard hatching were carried out at clean and clear rivers the Crystal Palace, London, using ice from the Wenham Ice Co. Boston USA. The first attempt to transport Salmon ova was by Gottlieb Boccius in 1852 aboard the “Columbus”. The Tasmanian Government announced a reward of Wooden Troughs holding 60 gallons of water were 500 pounds in 1857 for the introduction of live slung gimbal style amid-ship, hoping the little ova Atlantic salmon [not live ova]. That was little would handle the sea trip. The experiment failed the support for JAY. water temperature was not controlled plus the ova Edward Wilson who was a part-owner and editor of had no protection The Argus newspaper in Melbourne, and also founded the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria As James Youl is prominent in my address tonight persuaded the Society to offer 600 pounds to his I’ll provide his back ground. good friend James Youl to organize and manage a He was born Dec. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

C-( : ,i; [Mitn'i PAPERS & PROCEEDINGS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OP TASMANIA, • ^ FOR THE YEARS I 898- I 899. (ISSUED JUNE, 1900. (Bf^^^ ^^V0% ®aamania PRINTED BY DAVIKS BROTHERS LIMITED, MACQUARIE STREET, HOBART, 1900. The responsibility of the Statements and Opinions given in the following Papers and Discussions rests with the individual Authors; the Society as a body merely places them on record. : : : ROYAL SOCIETY OF TASMANIA. -»o>0{oo- Patroti HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN. HIS EXCELLENCY VISCOUNT GORMANSTON, G.C.M.G. THE HON. SIR JAMES WILSON AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C. R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.S.S. THOMAS STEPHENS, ESQ., MA., F.G.S. HIS LORDSHIP THE BISHOP OF TASMANIA. C^OtXttCii : * T. STEPHENS, ESQ., M.A., F.G.S. * C. J. BARCLAY, ESQ. " R. S. BRIGHT. ESQ., M.R.C.S.E. * A. G. WEBSTER, ESQ. HIS LORDSHIP THE BISHOP OF TASMANIA. RUSSELL YOUNG, ESQ. HON. C. H. GRANT, M.E.C. BERNARD SHAW, ESQ. COL. W. V. LEGGE, R.A. R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.L.S. HON. N. J. BROWN, M.E.C. HON. SIR J. W. AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C. llttMtor of ^ccnunU: R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.S.S. Hon. eTreajstirer C. J. BARCLAY, ESQ. ^ecretarg anti librarian ALEXANDER MORTON. * Members who next retire in rotation . ^onimt^. A. Page. A.A.A.S. Congratulations ... ... ... ... ... ... xvii A.A.A.S. 1902 Meeting. Deputation to the Government Novem- ber2nd, 1899 LVii Agnew, Sir James, Unveiling a Portrait of... .. ... ... xxxviii Agnew, Sir James, Letter from . -

The Library of Daniel Garrison Brinton

The Library of Daniel Garrison Brinton The Library of Daniel Garrison Brinton John M. Weeks With the assistance of Andree Suplee, Larissa M. Kopytoff, and Kerry Moore University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Copyright © 2002 University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology 3260 South Street Philadelphia, PA 19104-6324 All rights reserved. First Edition Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data University of Pennsylvania. Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The library of Daniel Garrison Brinton / University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology ; John M. Weeks with the assistance of Andree Suplee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-931707-46-4 (alk. paper) 1. Brinton, Daniel Garrison, 1837-1899—Ethnolgical collections. 2. Books—Private collections—Pennsylvania—Philadelphia. 3. University of Pennsylvania. Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Library—Ethnological collections. 4. Libraries—Pennsylvania—Philadelphia x Special collections. I. Weeks, John M. II. Suplee, Andree. III. Title. GN36.U62 P487 2002b 018'.2--dc21 2002152502 John M. Weeks is Museum Librarian at the University of Pennsylvania. His other bibliographic publications include Middle American Indians: A Guide to the Manuscript Collec- tion at Tozzer Library, Harvard University (Garland, 1985), Maya Ethnohistory: A Guide to Spanish Colonial Documents at Tozzer Library, Harvard University (Vanderbilt University Publications in Anthropology, 1987), Mesoamerican Ethnohistory in United States Libraries: Reconstruction of the William E. Gates Collection of Historical and Linguistic Manuscripts (Labyrinthos, 1990), Maya Civilization (Garland, 1992; Labyrinthos, 1997, 2002), and Introduction to Library Re- search in Anthropology (Westview Press, 1991, 1998). Since 1972 he has conducted exca- vations in Guatemala, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic. -

Foreign Bodies: Oceania and the Science of Race 1750–1940

Foreign Bodies Oceania and the Science of Race 1750-1940 Foreign Bodies Oceania and the Science of Race 1750-1940 Edited by Bronwen Douglas and Chris Ballard Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/foreign_bodies_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Foreign bodies : Oceania and the science of race 1750-1940 / editors: Bronwen Douglas, Chris Ballard. ISBN: 9781921313998 (pbk.) 9781921536007 (online) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Ethnic relations. Race--Social aspects. Oceania--Race relations. Other Authors/Contributors: Douglas, Bronwen. Ballard, Chris, 1963- Dewey Number: 305.800995 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Noel Wendtman. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press For Charles, Kirsty, Allie, and Andrew and For Mem, Tessa, and Sebastian Table of Contents Figures ix Preface xi Editors’ Biographies xv Contributors xvii Acknowledgements xix Introduction Foreign Bodies in Oceania 3 Bronwen Douglas Part One – Emergence: Thinking the Science of Race, 1750-1880 Chapter 1. Climate to Crania: science and the racialization of human 33 difference Bronwen Douglas Part Two – Experience: the Science of Race and Oceania, 1750-1869 Chapter 2. ‘Novus Orbis Australis’: Oceania in the science of race, 1750-1850 99 Bronwen Douglas Chapter 3. ‘Oceanic Negroes’: British anthropology of Papuans, 1820-1869 157 Chris Ballard Part Three – Consolidation: the Science of Race and Aboriginal Australians, 1860-1885 Chapter 4. -

The Mutilation of William Lanne in 1869 and Its Aftermath

The Last Man: The mutilation of William Lanne in 1869 and its aftermath Stefan Petrow Regarding the story of King Billy's Head, there are so many versions of it that it might be as well if you sent the correct details} In 1869 William Lanne, the last 'full-blooded' Tasmanian Aboriginal male, died.1 2 Lying in the Hobart Town General Hospital, his dead body was mutilated by scientists com peting for the right to secure the skeleton. The first mutilation by Dr. William Lodewyk Crowther removed Lanne's head. The second mutilation by Dr. George Stokell and oth ers removed Lanne's hands and feet. After Lanne's burial, Stokell and his colleagues removed Lanne's body from his grave before Crowther and his party could do the same. Lanne's skull and body were never reunited. They were guarded jealously by the respective mutilators in the interests of science. By donating Lanne's skeleton, Crowther wanted to curry favour with the prestigious Royal College of Surgeons in London, while Stokell, anxious to retain his position as house-surgeon at the general hospital, wanted to cultivate good relations with the powerful men associated with the Royal Society of Tasmania. But, perhaps because of the scandal associated with the mutilation, no scientific study of Lanne's skull or skeleton was ever published or, as far as we know, even attempted. It seems that Lanne was mutilated to satisfy the egos and 'personal ambition' of desperate men, who wanted a memento of Tasmania's last man, as the newspapers of the time called him.3 Unsurprisingly, the Lanne affair has held an enduring fascination for scholars of Tasmanian history.4 Lanne's mutilation symbolised the dispossession of land from the Tasmanian Aboriginals and its carving up by racially intolerant and violent white set tlers, generally indifferent to the rights of the indigenous population. -

Foreign Bodies Oceania and the Science of Race 1750-1940

Foreign Bodies Oceania and the Science of Race 1750-1940 Foreign Bodies Oceania and the Science of Race 1750-1940 Edited by Bronwen Douglas and Chris Ballard Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/foreign_bodies_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Foreign bodies : Oceania and the science of race 1750-1940 / editors: Bronwen Douglas, Chris Ballard. ISBN: 9781921313998 (pbk.) 9781921536007 (online) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Ethnic relations. Race--Social aspects. Oceania--Race relations. Other Authors/Contributors: Douglas, Bronwen. Ballard, Chris, 1963- Dewey Number: 305.800995 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Noel Wendtman. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press For Charles, Kirsty, Allie, and Andrew and For Mem, Tessa, and Sebastian Table of Contents Figures ix Preface xi Editors’ Biographies xv Contributors xvii Acknowledgements xix Introduction Foreign Bodies in Oceania 3 Bronwen Douglas Part One – Emergence: Thinking the Science of Race, 1750-1880 Chapter 1. Climate to Crania: science and the racialization of human 33 difference Bronwen Douglas Part Two – Experience: the Science of Race and Oceania, 1750-1869 Chapter 2. ‘Novus Orbis Australis’: Oceania in the science of race, 1750-1850 99 Bronwen Douglas Chapter 3. ‘Oceanic Negroes’: British anthropology of Papuans, 1820-1869 157 Chris Ballard Part Three – Consolidation: the Science of Race and Aboriginal Australians, 1860-1885 Chapter 4.