Development of Tasmanian Water Right Legislation 1877-1885: a Tortuous Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

~. ~. ~••r __._ .,'__, __----., The National Ubrary supplies copies of this article under licence from the Copyright Agency Limited (GAL). Further reproductions of this' article can only be made under licence. ·111111111111 200003177 . J The Last Man: The mutilation ofWilliam Lanne in 1869 and its aftermath Stefan Petrow Regarding the story of King Billy's Head, there are so many versions of it that it might be as well if you sent rhe correct details.! In 1869 William Lanne, the last 'full-blooded' Tasmanian Aboriginal male, died.2 Lying in the Hobart Town General Hospital, his dead body was mutilated by scientists com peting for the right to secure the skeleton. The first mutilation by Dr. William Lodewyk Crowther removed Lanne's head. The second mutilation by Dr. George Stokell and oth ers removed Lanne's hands and feet. After Lanne's burial, Stokell and his colleagues removed Lanne's body from his grave before Crowther and his party could do the same. Lanne's skull and body were never reunited. They were guarded jealously by the respective mutilators in the interests of science. By donating Lanne's skeleton, Crowther wanted to curry favour with the prestigious Royal College of Surgeons in London, while Stokell, anxious to retain his position as house-surgeon at the general hospital, wanted to cultivate good relations with the powerful men associated with the Royal Society of Tasmania. But, perhaps because of the scandal associated with the mutilation, no scientific study of Lanne's skull or skeleton was ever published or, as far as we know, even attempted. -

A Place in the Empire: Negotiating the Life Of

i A PLACE IN THE EMPIRE: NEGOTIATING THE LIFE OF GERTRUDE KENNY Miranda Elizabeth Morris, BA (History)Murdoch; PD (Public History), Murdoch. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania June 2010 i This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief, no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. Miranda Elizabeth Morris ii This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968 Miranda Elizabeth Morris iii ABSTRACT In the winter of 1879 a riot broke out at the New Norfolk Hospital for the Insane in Tasmania. The focus was an effigy dressed in a frock and cap that was set alight amidst a cacophony of rough music. The figure represented the Matron, Gertrude Kenny. Exploring one woman's biographical trajectory, this thesis will examine the tensions and interrelationships between identity formation and imperial ideals of class, race and gender. Gertrude Kenny migrated from Britain to Tasmania in 1858, working initially as a parlourmaid to an Anglo-Indian family and then as a nursery governess of a family implicated in the a scandal over Aboriginal remains collected for the Royal College of Surgeons and whose fortunes were tied up with Kenny's own. In 1870 she became a matron, first training neglected and wayward girls for service and then, in 1878, at a hospital for the insane. -

The Effect of Poverty and Politics on the Development of Tasmanian

THE EFFECT OF POVERTY AND POLITICS ON THE DEVELOPMENT . OF TASMANIAN STATE EDUCATION. .1.900 - 1950 by D.V.Selth, B.A., Dip.Ed. Admin. submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. UNIVERSITi OF TASMANIA HOBART 1969 /-4 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no copy or paraphrase of material previously published or written by another person, except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. 0 / la D.V.Selth. STATEMENT OF THESIS Few Tasmanians believed education was important in the early years of the twnntieth century, and poverty and conservatism were the most influential forces in society. There was no public pressure to compel politicians to assist the development of education in the State, or to support members of the profession who endeavoured to do so. As a result 7education in Tasmania has been more influenced by politics than by matters of professionL1 concern, and in turn the politicians have been more influenced'by the state of the economy than the needs of the children. Educational leadership was often unproductive because of the lack of political support, and political leadership was not fully productive because its aims were political rather than educational. Poverty and conservatism led to frustration that caused qualified and enthusiastic young teachers to seek higher salaries and a more congenial atmosphere elsewhere, and also created bitterness and resentment of those who were able to implement educational policies, with less dependence , on the state of the economy or the mood of Parliament. -

The Federal Movement in Tasmania, 1880-1900

THE FEDERAL MOVEMENT IN TASMANIA 1880 — 1900 by C.J. CRAIG B.A. Hons. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of: MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA HOBART 31st December 1971. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university, and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no copy or paraphrase of material previously published or written by another person, except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. C.J. CRAIG. 31 December, 1971. CONTENTS Page CHRONOLOGY INTRODUCTION I THE POLITICIANS, THE PRESS & THE FEDERAL COUNCIL 15 1, The Politicians 2. The Press 27 3. The Federal Council 34. II THE FIRST FEDERAL DRAFT CONSTITUTION 58 10 Preliminaries 5e 2. The Federal Convention in Sydney 89 III REACTIONS TO TFE DRAFT BILL IN TASMANIA 115 10 The Reaction of the Press and Public 115 2. The Debate in Parliament 120 3. The Failure of the Federal Enabling Bill 139 IV THE DOLDRUMS, 1892-94 146 10 Economic Crisis and the Federal Council 146 2. The Federal Council Session of 1893 161 30 More Tasmanian Moves 174 V FEDERATION ON THE MOVE AGAIN 190 10 The Premiers' Conference of 1895 190 2. The Passing of the Tasmanian 'Federal Enabling Bill 213 VI TgE FEDERAL CONVENTION, 1897-98 234 1. The Election of Delegates 234 2. The Adelaide Session 257 3. The Tasmanian Amendments 273 40 The Braddon Blot 281 VII THE FEDERAL R7FET1ENDUMS, 1898& 1899 303 1. The Campaign in Tasmania 303 2. -

Brothers Under Arms, the Tasmanian Volunteers

[An earlier version was presented to Linford Lodge of Research. The improved version, below, was to have been presented to the Discovery Lodge of Research on 6 September 2012, but, owing to illness of the author, was simply published in the Transactions of Discovery Lodge in October 2012.] Brothers under Arms, the Tasmanian Volunteers by Bro Tony Pope Introduction For most of my life, as a newspaper reporter, police officer, and Masonic researcher, I have been guided by the advice of that sage old journalist, Bro Rudyard Kipling:1 I keep six honest serving men (They taught me all I knew); Their names are What and Why and When And How and Where and Who. But this paper is experimental, in that I have also taken heed of the suggestions of three other brethren: Bro Richard Dawes, who asked the speakers at the Goulburn seminar last year to preface their talks with an account of how they set about researching and preparing their papers; Bro Bob James, who urges us to broaden the scope of our research, to present Freemasonry within its social context, and to emulate Socrates rather than Moses in our presentation; and Bro Trevor Stewart, whose advice is contained in the paper published in the July Transactions, ‘The curious case of Brother Gustav Petrie’. Tasmania 1995 Rudyard Kipling Richard Dawes Bob James Trevor Stewart I confess that I have not the slightest idea how to employ the Socratic method in covering my chosen subject, and I have not strained my brain to formulate Bro Stewart’s ‘third order or philosophical’ questions, but within those limitations this paper is offered as an honest attempt to incorporate the advice of these brethren. -

L'ton Thematic History Report

LAUNCESTON HERITAGE STUDY STAGE 1: THEMATIC HISTORY Prepared by Ian Terry & Nathalie Servant for Launceston City Council July 2002 © Launceston City Council Cover. Launceston in the mid nineteenth century (Sarah Ann Fogg, Launceston: Tamar Street Bridge area , Allport Library & Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania). C O N T E N T S The Study Area ........................................................................................................................1 The Study .................................................................................................................................2 Authorship................................................................................................................................2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................2 Acknowledgments....................................................................................................................3 Abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................3 HISTORIC CONTEXT Introduction..............................................................................................................................4 1 Environmental Context .........................................................................................................5 2 Human Settlement.................................................................................................................6 -

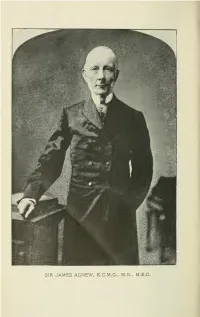

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©Bititarn*

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©bititarn* Sir James Wilson Agnew, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C., Senior Vice-President of the Royal Society of Tas- mania. Died on cSth November, 1901, in the 87th year of his age. —Born at Ballyclare, Ireland, on the 2nd October, 1815, he studied for the medical profession in London and Paris, and at Glas^^-ow, where he graduated M.D., as his father and grandfather had done before him, and came to Australia in 1839. After a short stay in New South Wales and Victoria (then known as Port Phillip), he accepted from Sir John Franklin the offer of appointment as medical officer to an important station at Tasman's Peninsula, wliere he devoted the greater part of his leisure time to the study of natural history. Prior to his removal to Hobart for the more extended practice of his profession, in which he sub- sequently attained a position of acknowledged eminence, he had assisted in founding the Tasmanian Societ}^, and lie became an active member of the Royal Society, into which the former Society merged in 1844. Shortly after the retirement of Dr. Milligan, its Secretary and Curator, in 1860, he undertook the duties of Seci'etary as a labour of love, in order that the whole of the limited amount available out of income might be appropriated as salary for the Curator of the Museum. From that time on- wards, except during occasional periods of absence from Tasmania, he continued to act as chief executive officer of the Royal Society in the capacity of Honorary Secretary for many years, and latterly in that of Chairman of the Council ; and to the admirable manner in which those self-imposed duties were discharo-ed. -

The Constitution Makers

The 1897 Federal Convention Election: a Success or Failure? The 1897 Federal Convention Election: a Success or Failure?* Kathleen Dermody Federation for years past had been like a water-logged hulk; it could not make headway, but it still lay in the offing, watching and longing for the pilot and the tug. The people are the tug, to fetch it into the harbour of victory.1 Federation—a Question for the People hroughout the early 1890s politicians used federation as a plaything, picking it up and Tputting it down according to political whim and personal ambition: the people, tired with such toying, shrugged their shoulders at the prospect of Australian union and turned their attention elsewhere. To give the movement vigour, the friends of federation constantly referred to the need to involve the people. This paper will look at the popular election of delegates from New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania to the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897–98 and the attempts made during the campaign to arouse people to the importance of federation. The Western Australian Parliament decided that members of Parliament, not the people, would have the responsibility for electing delegates to the convention and so Western Australia is not considered in this paper; nor is Queensland which shunned the Convention. One of the main reasons for opening the doors of the 1891 federal convention to the public was the desire of the delegates to win over the confidence of the people and to cultivate their sympathies for federation. This convention, consisting of delegates appointed by the Parliament of each of the six Australian colonies and New Zealand, succeeded in adopting a draft constitution in the form of a Draft of a Bill to Constitute the Commonwealth of * Dr Kathleen Dermody is a Principal Research Officer in the Committee Office of the Senate. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

Clonal Sncittn oi Casmanhi. ABSTRACT OF PHOCEELINaS, APPwIL 29th, 1902. A meeting of the Eoyal Socie!;y of Tas- and expansive beyond any limit they mania was held on Tuesday evening, April could assign to it.'" The Fellows had 29, 1902, in the society^s new room, Argyle- done very well so far. They had got s'treet. The President, His Excellency natural history specimens, and a fairly the GrOTernor, Sir Arthur Havelook, good rep.resantation of art, and, on tlie G.C.S.I., G.'C.M.G., presided. The Go- whole, he thought the institution would vernor was accompanied by Lady Have- compare favourably with any institution lock and Captain Gaskell, A.D.C. in the other States. But they could say now. as the secretary said in 18o7, that the Welcome to the New President. society must be cumulative and expan- sive beyond any limit thsy could a».-ign The Hon. Nicholas J. Brown, Speaker to it. Its first expansion now should be of the House of Assembly, and Vice-Presi- in the direction of the securing and equip- dent of the Eoyal Society, said he was ment of a Techuological museum. I'hat charged with a duty of a y&i:y pleasant seemed to be necessary, in view of the an- character. He had, on behalf of the ticipations that, in the near fature, Tas- Fellows of the Eoyal Society, to welcome mania would become an important manu- His Excellency on that, the first, occasion facturing and distributing centre for the of fTiS presiding at a meeting of the Eel- whole of Australia. -

Melbourne Club Address 12Th Aug 09

J Michael M Youl The success of his experiment may have been the TASMANIAN Club address 6 July 2012 fore runner to storing animal and human semen and storing animal and human fertile eggs, IVF and so Good evening Gentlemen on [now I’m really out of my depth]. In the 1850’s and 60’s there was a strong desire by Packaging took a great deal of sorting out. James colonist in Tasmania and Victoria to introduce Youl spent 10 years to find the right mix. His Atlantic salmon [ salmo salar ] to our beautiful experiments to retard hatching were carried out at clean and clear rivers the Crystal Palace, London, using ice from the Wenham Ice Co. Boston USA. The first attempt to transport Salmon ova was by Gottlieb Boccius in 1852 aboard the “Columbus”. The Tasmanian Government announced a reward of Wooden Troughs holding 60 gallons of water were 500 pounds in 1857 for the introduction of live slung gimbal style amid-ship, hoping the little ova Atlantic salmon [not live ova]. That was little would handle the sea trip. The experiment failed the support for JAY. water temperature was not controlled plus the ova Edward Wilson who was a part-owner and editor of had no protection The Argus newspaper in Melbourne, and also founded the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria As James Youl is prominent in my address tonight persuaded the Society to offer 600 pounds to his I’ll provide his back ground. good friend James Youl to organize and manage a He was born Dec. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

C-( : ,i; [Mitn'i PAPERS & PROCEEDINGS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OP TASMANIA, • ^ FOR THE YEARS I 898- I 899. (ISSUED JUNE, 1900. (Bf^^^ ^^V0% ®aamania PRINTED BY DAVIKS BROTHERS LIMITED, MACQUARIE STREET, HOBART, 1900. The responsibility of the Statements and Opinions given in the following Papers and Discussions rests with the individual Authors; the Society as a body merely places them on record. : : : ROYAL SOCIETY OF TASMANIA. -»o>0{oo- Patroti HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN. HIS EXCELLENCY VISCOUNT GORMANSTON, G.C.M.G. THE HON. SIR JAMES WILSON AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C. R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.S.S. THOMAS STEPHENS, ESQ., MA., F.G.S. HIS LORDSHIP THE BISHOP OF TASMANIA. C^OtXttCii : * T. STEPHENS, ESQ., M.A., F.G.S. * C. J. BARCLAY, ESQ. " R. S. BRIGHT. ESQ., M.R.C.S.E. * A. G. WEBSTER, ESQ. HIS LORDSHIP THE BISHOP OF TASMANIA. RUSSELL YOUNG, ESQ. HON. C. H. GRANT, M.E.C. BERNARD SHAW, ESQ. COL. W. V. LEGGE, R.A. R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.L.S. HON. N. J. BROWN, M.E.C. HON. SIR J. W. AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C. llttMtor of ^ccnunU: R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.S.S. Hon. eTreajstirer C. J. BARCLAY, ESQ. ^ecretarg anti librarian ALEXANDER MORTON. * Members who next retire in rotation . ^onimt^. A. Page. A.A.A.S. Congratulations ... ... ... ... ... ... xvii A.A.A.S. 1902 Meeting. Deputation to the Government Novem- ber2nd, 1899 LVii Agnew, Sir James, Unveiling a Portrait of... .. ... ... xxxviii Agnew, Sir James, Letter from . -

Volume 39, Issue 1

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 39 Issue 1 June 2012 Article 1 January 2012 Volume 39, Issue 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation (2012) "Volume 39, Issue 1," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 39 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol39/iss1/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol39/iss1/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY NEWSLETTER VOLUME 39.1 JUNE 2012 History of Anthropology Newsletter 39.1 (June 2012) / 1 HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY NEWSLETTER VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 JUNE 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Utilization of Truganini’s Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania Antje Kühnast 3 Recent Bibliography, Websites of Interest, and Conference Report 12 19 Prize Announcement and Three Societies Conference Session of Interest 14 History of Anthropology Newsletter 39.1 (June 2012) / 2 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Henrika Kuklick, Editor [email protected] Peter Collopy, Assistant Editor [email protected] Matthew Hoffarth, Assistant Editor [email protected] Joanna Radin, Assistant Editor [email protected] Adrian Young, Assistant Editor [email protected] CORRESPONDING CONTRIBUTORS Ira Bashkow [email protected] Regna Darnell [email protected] Nélia Dias [email protected] Lise Dobrin [email protected] Christian Feest [email protected] Andre Gingrich [email protected] Robert Gordon [email protected] Curtis Hinsley [email protected] Edgardo Krebs [email protected] Esteban Krotz [email protected] H.