PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brothers Under Arms, the Tasmanian Volunteers

[An earlier version was presented to Linford Lodge of Research. The improved version, below, was to have been presented to the Discovery Lodge of Research on 6 September 2012, but, owing to illness of the author, was simply published in the Transactions of Discovery Lodge in October 2012.] Brothers under Arms, the Tasmanian Volunteers by Bro Tony Pope Introduction For most of my life, as a newspaper reporter, police officer, and Masonic researcher, I have been guided by the advice of that sage old journalist, Bro Rudyard Kipling:1 I keep six honest serving men (They taught me all I knew); Their names are What and Why and When And How and Where and Who. But this paper is experimental, in that I have also taken heed of the suggestions of three other brethren: Bro Richard Dawes, who asked the speakers at the Goulburn seminar last year to preface their talks with an account of how they set about researching and preparing their papers; Bro Bob James, who urges us to broaden the scope of our research, to present Freemasonry within its social context, and to emulate Socrates rather than Moses in our presentation; and Bro Trevor Stewart, whose advice is contained in the paper published in the July Transactions, ‘The curious case of Brother Gustav Petrie’. Tasmania 1995 Rudyard Kipling Richard Dawes Bob James Trevor Stewart I confess that I have not the slightest idea how to employ the Socratic method in covering my chosen subject, and I have not strained my brain to formulate Bro Stewart’s ‘third order or philosophical’ questions, but within those limitations this paper is offered as an honest attempt to incorporate the advice of these brethren. -

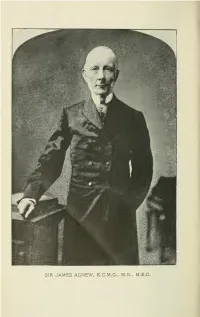

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©Bititarn*

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©bititarn* Sir James Wilson Agnew, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C., Senior Vice-President of the Royal Society of Tas- mania. Died on cSth November, 1901, in the 87th year of his age. —Born at Ballyclare, Ireland, on the 2nd October, 1815, he studied for the medical profession in London and Paris, and at Glas^^-ow, where he graduated M.D., as his father and grandfather had done before him, and came to Australia in 1839. After a short stay in New South Wales and Victoria (then known as Port Phillip), he accepted from Sir John Franklin the offer of appointment as medical officer to an important station at Tasman's Peninsula, wliere he devoted the greater part of his leisure time to the study of natural history. Prior to his removal to Hobart for the more extended practice of his profession, in which he sub- sequently attained a position of acknowledged eminence, he had assisted in founding the Tasmanian Societ}^, and lie became an active member of the Royal Society, into which the former Society merged in 1844. Shortly after the retirement of Dr. Milligan, its Secretary and Curator, in 1860, he undertook the duties of Seci'etary as a labour of love, in order that the whole of the limited amount available out of income might be appropriated as salary for the Curator of the Museum. From that time on- wards, except during occasional periods of absence from Tasmania, he continued to act as chief executive officer of the Royal Society in the capacity of Honorary Secretary for many years, and latterly in that of Chairman of the Council ; and to the admirable manner in which those self-imposed duties were discharo-ed. -

Development of Tasmanian Water Right Legislation 1877-1885: a Tortuous Process

Journal of Australasian Mining History, Vol. 15, 2017 Development of Tasmanian water right legislation 1877-1885: a tortuous process By KEITH PRESTON rior to the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, a right to water was governed by the riparian doctrine, a common law principle of entitlement that was established P in Great Britain during the 15th and 16th centuries.1 Water entitlements were tied to land ownership whereby the occupant could access a watercourse flowing through a landholding or along its boundary. This doctrine was introduced to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land in 1828 with the passing of the Australian Courts Act (9 Geo. No. 4) that transferred ‘all laws and statutes in force in the realm of England’.2 The riparian doctrine became part of New South Wales common law following a Supreme Court ruling in 1859.3 During the Californian and Victorian gold rushes, the principle of prior appropriation was established to protect the rights of mining leaseholders on crown land but riparian rights were retained for other users, particularly for irrigation of private land. The principle of prior appropriation was based on first possession, which established priority when later users obtained water from a common source, although these rights could be traded and were a valuable asset in the regulation of water supply to competing claims on mining fields.4 In Tasmania, disputes over water rights between 1881-85 challenged the application of these two doctrines, forcing repeated revision of legislation. The Tasmanian Parliament passed the first gold mining legislation in September 1859, eight years after the first gold rushes in Victoria and New South Wales, which marked the widespread introduction of alluvial mining in Australia. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

Clonal Sncittn oi Casmanhi. ABSTRACT OF PHOCEELINaS, APPwIL 29th, 1902. A meeting of the Eoyal Socie!;y of Tas- and expansive beyond any limit they mania was held on Tuesday evening, April could assign to it.'" The Fellows had 29, 1902, in the society^s new room, Argyle- done very well so far. They had got s'treet. The President, His Excellency natural history specimens, and a fairly the GrOTernor, Sir Arthur Havelook, good rep.resantation of art, and, on tlie G.C.S.I., G.'C.M.G., presided. The Go- whole, he thought the institution would vernor was accompanied by Lady Have- compare favourably with any institution lock and Captain Gaskell, A.D.C. in the other States. But they could say now. as the secretary said in 18o7, that the Welcome to the New President. society must be cumulative and expan- sive beyond any limit thsy could a».-ign The Hon. Nicholas J. Brown, Speaker to it. Its first expansion now should be of the House of Assembly, and Vice-Presi- in the direction of the securing and equip- dent of the Eoyal Society, said he was ment of a Techuological museum. I'hat charged with a duty of a y&i:y pleasant seemed to be necessary, in view of the an- character. He had, on behalf of the ticipations that, in the near fature, Tas- Fellows of the Eoyal Society, to welcome mania would become an important manu- His Excellency on that, the first, occasion facturing and distributing centre for the of fTiS presiding at a meeting of the Eel- whole of Australia. -

Melbourne Club Address 12Th Aug 09

J Michael M Youl The success of his experiment may have been the TASMANIAN Club address 6 July 2012 fore runner to storing animal and human semen and storing animal and human fertile eggs, IVF and so Good evening Gentlemen on [now I’m really out of my depth]. In the 1850’s and 60’s there was a strong desire by Packaging took a great deal of sorting out. James colonist in Tasmania and Victoria to introduce Youl spent 10 years to find the right mix. His Atlantic salmon [ salmo salar ] to our beautiful experiments to retard hatching were carried out at clean and clear rivers the Crystal Palace, London, using ice from the Wenham Ice Co. Boston USA. The first attempt to transport Salmon ova was by Gottlieb Boccius in 1852 aboard the “Columbus”. The Tasmanian Government announced a reward of Wooden Troughs holding 60 gallons of water were 500 pounds in 1857 for the introduction of live slung gimbal style amid-ship, hoping the little ova Atlantic salmon [not live ova]. That was little would handle the sea trip. The experiment failed the support for JAY. water temperature was not controlled plus the ova Edward Wilson who was a part-owner and editor of had no protection The Argus newspaper in Melbourne, and also founded the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria As James Youl is prominent in my address tonight persuaded the Society to offer 600 pounds to his I’ll provide his back ground. good friend James Youl to organize and manage a He was born Dec. -

Reference to the Index of John Reynolds

Reynolds DX.17 Donated by John and Prof. Henry Reynolds 1985 Access: open for consultation JOHN REYNOLDS John Reynolds (1899-1986) was educated at Friends' Schovl, Hobart, and Hobart Technical School, where he studied chemistry. He had a distinguished career as a metallurgist, starting with the E.Z.Co., and played a leading role in the establishment of the Australian aluminium industry with its beginnings at Bell Bay following the discovery of bauxite at Ouse in 1943. In 1939, at the beginning of the War, he was seconded to the Public Service as Commerce Officer, Department of Agriculture, Commerce & Industry Section, Hobart, to advise on the production of industrial charcoal for carbide manufacture. He was involved in making a contract for the sale of wolfram and tungsten to the British Government. He held a number of advisory and official posts in Tasmania during the next two decades, including responsibility for the implementation of the Grain Reserve Act 1950. John Reynolds main interest, however, lay in journalism and historical research. He won a Commonwealth Literary Fund Award for his biography of Toby Barton. He wrote a life of William Lawrence Baillieu, Launceston - the history of an Australian City (1969); Men &Mines (1974) and articles for the Australian Dictionary of Biography and the Transactions of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association. His last book, Countries of the mind, a biography of Edmund Morris Miller, completed in collaboration with Margaret Giordano, was published in 1987 after his death. DIARIES DX.17/ 1 Desk diaries 1945, 1950, 1955, 1960, 1976 Appointments and memoranda. MINING & BUSINESS 2 Australian Magnesium Co. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

C-( : ,i; [Mitn'i PAPERS & PROCEEDINGS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OP TASMANIA, • ^ FOR THE YEARS I 898- I 899. (ISSUED JUNE, 1900. (Bf^^^ ^^V0% ®aamania PRINTED BY DAVIKS BROTHERS LIMITED, MACQUARIE STREET, HOBART, 1900. The responsibility of the Statements and Opinions given in the following Papers and Discussions rests with the individual Authors; the Society as a body merely places them on record. : : : ROYAL SOCIETY OF TASMANIA. -»o>0{oo- Patroti HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN. HIS EXCELLENCY VISCOUNT GORMANSTON, G.C.M.G. THE HON. SIR JAMES WILSON AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C. R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.S.S. THOMAS STEPHENS, ESQ., MA., F.G.S. HIS LORDSHIP THE BISHOP OF TASMANIA. C^OtXttCii : * T. STEPHENS, ESQ., M.A., F.G.S. * C. J. BARCLAY, ESQ. " R. S. BRIGHT. ESQ., M.R.C.S.E. * A. G. WEBSTER, ESQ. HIS LORDSHIP THE BISHOP OF TASMANIA. RUSSELL YOUNG, ESQ. HON. C. H. GRANT, M.E.C. BERNARD SHAW, ESQ. COL. W. V. LEGGE, R.A. R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.L.S. HON. N. J. BROWN, M.E.C. HON. SIR J. W. AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C. llttMtor of ^ccnunU: R. M. JOHNSTON, ESQ., F.S.S. Hon. eTreajstirer C. J. BARCLAY, ESQ. ^ecretarg anti librarian ALEXANDER MORTON. * Members who next retire in rotation . ^onimt^. A. Page. A.A.A.S. Congratulations ... ... ... ... ... ... xvii A.A.A.S. 1902 Meeting. Deputation to the Government Novem- ber2nd, 1899 LVii Agnew, Sir James, Unveiling a Portrait of... .. ... ... xxxviii Agnew, Sir James, Letter from . -

Volume 39, Issue 1

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 39 Issue 1 June 2012 Article 1 January 2012 Volume 39, Issue 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation (2012) "Volume 39, Issue 1," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 39 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol39/iss1/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol39/iss1/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY NEWSLETTER VOLUME 39.1 JUNE 2012 History of Anthropology Newsletter 39.1 (June 2012) / 1 HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY NEWSLETTER VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 JUNE 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Utilization of Truganini’s Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania Antje Kühnast 3 Recent Bibliography, Websites of Interest, and Conference Report 12 19 Prize Announcement and Three Societies Conference Session of Interest 14 History of Anthropology Newsletter 39.1 (June 2012) / 2 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Henrika Kuklick, Editor [email protected] Peter Collopy, Assistant Editor [email protected] Matthew Hoffarth, Assistant Editor [email protected] Joanna Radin, Assistant Editor [email protected] Adrian Young, Assistant Editor [email protected] CORRESPONDING CONTRIBUTORS Ira Bashkow [email protected] Regna Darnell [email protected] Nélia Dias [email protected] Lise Dobrin [email protected] Christian Feest [email protected] Andre Gingrich [email protected] Robert Gordon [email protected] Curtis Hinsley [email protected] Edgardo Krebs [email protected] Esteban Krotz [email protected] H. -

Land Allocation in Tasmania Under the Waste Lands Acts, 1856-1889

i Cronyism, Muddle and Money: Land Allocation in Tasmania under the Waste Lands Acts, 1856-1889 Bronwyn Meikle Grad Dip Hum (University of Tasmania 2007), B Business (Accounting) (CQU 2004), B Education (BCAE 1989), G Dip Teacher-Librarianship (BCAE 1980), Cert Teaching (KGCAE 1969). Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, August 2014 ii This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Bronwyn Dorothy Meikle iii This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree in any tertiary institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. Bronwyn Dorothy Meikle iv Abstract With the granting of self-government to the colonies of eastern Australia in the 1850s, each colony became responsible for its own land legislation. Each produced legislation that enabled settlement by small farmers, the selectors. In New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland this led to conflict between the selectors and those who had previously established their sheep runs on the land, the squatters, as they became known in Australia. The land legislation also enabled the development of agriculture in those colonies. Tasmania produced twenty-one Waste Lands Acts over a period of thirty-one years, and introduced a number of land schemes to attract immigrants. In spite of these attempts, the Tasmanian economy remained in depression, agricultural output declined, and immigration stagnated. -

The Mutilation of William Lanne in 1869 and Its Aftermath

The Last Man: The mutilation of William Lanne in 1869 and its aftermath Stefan Petrow Regarding the story of King Billy's Head, there are so many versions of it that it might be as well if you sent the correct details} In 1869 William Lanne, the last 'full-blooded' Tasmanian Aboriginal male, died.1 2 Lying in the Hobart Town General Hospital, his dead body was mutilated by scientists com peting for the right to secure the skeleton. The first mutilation by Dr. William Lodewyk Crowther removed Lanne's head. The second mutilation by Dr. George Stokell and oth ers removed Lanne's hands and feet. After Lanne's burial, Stokell and his colleagues removed Lanne's body from his grave before Crowther and his party could do the same. Lanne's skull and body were never reunited. They were guarded jealously by the respective mutilators in the interests of science. By donating Lanne's skeleton, Crowther wanted to curry favour with the prestigious Royal College of Surgeons in London, while Stokell, anxious to retain his position as house-surgeon at the general hospital, wanted to cultivate good relations with the powerful men associated with the Royal Society of Tasmania. But, perhaps because of the scandal associated with the mutilation, no scientific study of Lanne's skull or skeleton was ever published or, as far as we know, even attempted. It seems that Lanne was mutilated to satisfy the egos and 'personal ambition' of desperate men, who wanted a memento of Tasmania's last man, as the newspapers of the time called him.3 Unsurprisingly, the Lanne affair has held an enduring fascination for scholars of Tasmanian history.4 Lanne's mutilation symbolised the dispossession of land from the Tasmanian Aboriginals and its carving up by racially intolerant and violent white set tlers, generally indifferent to the rights of the indigenous population. -

To View More Samplers Click Here

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently Australian Handbook 1878 Ref. AU0101-1878 ISBN: 978 1 74222 732 0 This book was kindly loaned to Archive Digital Books Australasia by the University of Queensland Library www.library.uq.edu.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

03 HA V&P INTRO V268 2015.Indd

JOURNALS OF THE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION OF THE FORTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA ANNO LXIIII ELIZ. II, 2015 Session 1 of the 48th Parliament Vol. 268 PRINTED BY MERCury-WALCH PTY LTD UNDER AUTHORITY OF THE GOVERNMENT OF THE State OF TASMANIA 315238 HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY ABSTRACT OF PETITIONS PRESENTED DURING 1ST SESSION OF 2015 SELECT COMMITTEES APPOINTED DURING 1ST SESSION OF 2014 LIST OF MEMBERS AND OFFICERS OF THE HOUSE PARLIAMENTS SINCE THE INTRODUCTION OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF EACH Ministry SINCE THE INTRODUCTION OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS, BEING THE JOURNALS OF THE HOUSE—Pages 248 to 562 NOTICES OF MOTION AND ORDERS OF THE Day—Pages 447 to 1044 NOTICES OF QUESTION—Pages 40 to 69 2 ABSTRACT OF PETITIONS presented to the House of Assembly during the First Session of the Forty-Eighth Parliament 2015—continued No. From Whom and Abstract of Prayer of Petition By Whom Date of Remarks Whence Presented Presented Presentation 1 535 Citizens of Tasmania Praying that the House call on the Govern- Mr Jaensch 4 March 2015 Received ment to consider installing traffic lights at the corner of Mount and Thorne Streets, Burnie 2 196 Citizens of Tasmania Praying that the Government reverse cuts to Mr Green 19 March 2015 Received the public education system 3 5621 Citizens of Tasmania Praying that no funding is reduced or health Mr White 18 August 2015 Received services be downgraded at the Mersey Com- munity Hospital 4 352 Citizens of Tasmania Praying the House acknowledge the current Ms Dawkins 17 November 2015