PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

~. ~. ~••r __._ .,'__, __----., The National Ubrary supplies copies of this article under licence from the Copyright Agency Limited (GAL). Further reproductions of this' article can only be made under licence. ·111111111111 200003177 . J The Last Man: The mutilation ofWilliam Lanne in 1869 and its aftermath Stefan Petrow Regarding the story of King Billy's Head, there are so many versions of it that it might be as well if you sent rhe correct details.! In 1869 William Lanne, the last 'full-blooded' Tasmanian Aboriginal male, died.2 Lying in the Hobart Town General Hospital, his dead body was mutilated by scientists com peting for the right to secure the skeleton. The first mutilation by Dr. William Lodewyk Crowther removed Lanne's head. The second mutilation by Dr. George Stokell and oth ers removed Lanne's hands and feet. After Lanne's burial, Stokell and his colleagues removed Lanne's body from his grave before Crowther and his party could do the same. Lanne's skull and body were never reunited. They were guarded jealously by the respective mutilators in the interests of science. By donating Lanne's skeleton, Crowther wanted to curry favour with the prestigious Royal College of Surgeons in London, while Stokell, anxious to retain his position as house-surgeon at the general hospital, wanted to cultivate good relations with the powerful men associated with the Royal Society of Tasmania. But, perhaps because of the scandal associated with the mutilation, no scientific study of Lanne's skull or skeleton was ever published or, as far as we know, even attempted. -

The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence 1860-1941

The Rifle Club Movement and Australian Defence 1860-1941 Andrew Kilsby A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences February 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the rifle club movement and its relationship with Australian defence to 1941. It looks at the origins and evolution of the rifle clubs and associations within the context of defence developments. It analyses their leadership, structure, levels of Government and Defence support, motivations and activities, focusing on the peak bodies. The primary question addressed is: why the rifle club movement, despite its strong association with military rifle shooting, failed to realise its potential as an active military reserve, leading it to be by-passed by the military as an effective force in two world wars? In the 19th century, what became known as the rifle club movement evolved alongside defence developments in the Australian colonies. Rifle associations were formed to support the Volunteers and later Militia forces, with the first ‘national’ rifle association formed in 1888. Defence authorities came to see rifle clubs, especially the popular civilian rifle clubs, as a cheap defence asset, and demanded more control in return for ammunition grants, free rail travel and use of rifle ranges. At the same time, civilian rifle clubs grew in influence within their associations and their members resisted military control. An essential contradiction developed. The military wanted rifle clubs to conduct shooting ‘under service conditions’, which included drill; the rifle clubs preferred their traditional target shooting for money prizes. -

THE TASMANIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL COMMUNITY MILESTONES 1 MAY - 31 MAY 2013 National Trust Heritage Festival 2013 Community Milestones

the NatioNal trust presents THE TASMANIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL COMMUNITY MILESTONES 1 MAY - 31 MAY 2013 national trust heritage Festival 2013 COMMUNITY MILESTONES message From the miNister message From tourism tasmaNia the month-long tasmanian heritage Festival is here again. a full program provides tasmanians and visitors with an opportunity to the tasmanian heritage Festival, throughout may 2013, is sure to be another successful event for thet asmanian Branch of the National participate and to learn more about our fantastic heritage. trust, showcasing a rich tapestry of heritage experiences all around the island. The Tasmanian Heritage Festival has been running for Thanks must go to the National Trust for sustaining the momentum, rising It is important to ‘shine the spotlight’ on heritage and cultural experiences, For visitors, the many different aspects of Tasmania’s heritage provide the over 25 years. Our festival was the first heritage festival to the challenge, and providing us with another full program. Organising a not only for our local communities but also for visitors to Tasmania. stories, settings and memories they will take back, building an appreciation in Australia, with other states and territories following festival of this size is no small task. of Tasmania’s special qualities and place in history. Tasmania’s lead. The month of May is an opportunity to experience and celebrate many Thanks must also go to the wonderful volunteers and all those in the aspects of Tasmania’s heritage. Contemporary life and visitor experiences As a newcomer to the State I’ve quickly gained an appreciation of Tasmania’s The Heritage Festival is coordinated by the National heritage sector who share their piece of Tasmania’s historic heritage with of Tasmania are very much shaped by the island’s many-layered history. -

A. I. Clark Papers

A. I. CLARK PAPERS PAPERS OF r-. i - ANDREW INGLIS CLARK AND HIS FAMILY DEPOSITED IN THE UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA ARCHIVES REF:C4 - II 1_ .1 ~ ) ) AI.CLARK INDEXOF NAMES NAME AGE DESCN DATE TOPIC REF Allen,J.H. lelter C4/C9,10 Allen,Mary W. letter C4/C11,12 AspinallL,AH. 1897 Clark's resign.fr.Braddon ministry C4/C390 Barton,Edmund 1849-1920 poltn.judge,GCMG.KC 1898 federation C4/C15 Bayles,J.E. 1885 Index": Tom Paine C4/H6 Berechree c.1905 Berechree v Phoenix Assurance Cc C4/D12 Bird,Bolton Stafford 1840-1924 1885 Brighton ejection C4/C16 Blolto,Luigi of Italy 1873-4 Pacific & USA voyage C4/C17,18 Bowden 1904-6? taxation appeal C4/D10 Braddon,Edward Nicholas Coventry 1829-1904 politn.KCMG 1897 Clark's resign. C4/C390 Brown,Nicholas John MHA Tas. 1887 Clark & Moore C4/C19 Burn,William 1887 Altny Gen.appt. C4/C20 Butler,Charles lawyer 1903 solicitor to Mrs Clark C4/C21 Butler,Gilbert E. 1897 Clark's resign. .C4/C390 Camm,AB 1883 visit to AIClark C4/C22-24 Clark & Simmons lawyers 1887,1909-18 C4/D1-17,K.4,L16 Clark,Alexander Inglis 1879-1931 sAl.C.engineer 1916,21-26 letters C4/L52-58,L Clark,Alexander Russell 1809-1894 engineer 1842-6,58-63 letter book etc. C4/A1-2 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 jUdge 1870-1907 papers C4/C-J Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 judge 1901 Acting Govnr.appt. C4/E9 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848·1907 jUdge 1907-32 estate of C4/K7,L281 Clark,Andrew Inglis 1848-1907 judge 1958 biog. -

The Influence of India on Colonial Tasmanian Architecture and Artefacts

The influence of India on colonial Tasmanian architecture and artefacts Lionel Morrell Background India has a long history of connections with Australia. Long before Captain Cook set foot on southern shores, cloth from ‘the Indies’ had traded its way from Gujarat and Coromandel down through the Indonesian archipelago to be traded with Aborigines by Makassar seamen negotiating seasonal camps to collect trepang, fish and pearl. According to Sharrad in Convicts, Call Centres and Cochin Kangaroos 1 it was men like Mitchell and Lang, from the 1820s on, who retired to land grants in Van Diemen’s Land and later other parts of Australia, who brought with them the verandahs of the Raj that became part of Australian architecture, and familiarity with India. As early as 1824, an attempt was made to found an institution for the sons of Anglo- Indians and British men in Van Diemen’s Land. Following the Indian mutiny of 1857, there was a rise in the numbers of Anglo-Indians settling in Australia, There were 372 Indian-born registered in 1881 2. Among them was Dr John Coverdale, born in 1814 in Kedgeree, Bengal, who was a medical practitioner at Richmond for many years. The term ‘Anglo-Indian’ was first used by Warren Hastings in the eighteenth century to describe both the British in India and their Indian-born children. 3 The first Anglo-Indian to settle in Tasmania was Rowland Walpole Loane in 1809, followed by many others, including Edward Dumaresq, a retired Indian Army officer who bought Mt Ireh in 1855 and lived there until his death in 1906 at the age of 104; Charles Swanston, who first came to VDL in 1828 on leave because of ill-health from his position as military paymaster in the provinces of Tranvancore and Tinnevelly in India and eventually settled here permanently in 1831 and Michael Fenton, who joined the 13 th Light Infantry in 1807 and served in India and Burma until 1828 when he sold his commission and emigrated to Van Diemen’s Land. -

Tasmanian Aborigines in the Furneaux Group in the Nine Teenth Century—Population and Land

‘I hope you will be my frend’: Tasmanian Aborigines in the Furneaux Group in the nine teenth century—population and land tenure Irynej Skira Abstract This paper traces the history of settlement of the islands of the Furneaux Group in Bass Strait and the effects of government regulation on the long term settlements of Tasma nian Aboriginal people from the 1850s to the early 1900s. Throughout the nineteenth century the Aboriginal population grew slowly eventually constituting approximately 40 percent of the total population of the Furneaux Group. From the 1860s outsiders used the existing land title system to obtain possession of the islands. Aborigines tried to establish tenure through the same system, but could not compete because they lacked capital, and were disadvantaged by isolation in their communication with gov ernment. Further, the islands' use for grazing excluded Aborigines who rarely had large herds of stock and were generally not agriculturalists. The majority of Aborigines were forced to settle on Cape Barren Island, where they built homes on a reserve set aside for them. European expansion of settlement on Flinders Island finally completed the disen franchisement of Aboriginal people by making the Cape Barren Island enclave depend ent on the government. Introduction In December 1869 Thomas Mansell, an Aboriginal, applied to lease a small island. He petitioned the Surveyor-General, T hope you will be my Frend...I am one of old hands Her, and haf Cast and have large family and no hum'.1 Unfortunately, he could not raise £1 as down payment. Mansell's was one of the many attempts by Aboriginal people in the Furneaux Group to obtain valid leasehold or freehold and recognition of their long term occupation. -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 21

Aboriginal History Volume twenty-one 1997 Aboriginal History Incorporated The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Secretary), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), Neil Andrews, Richard Baker, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Bill Humes, Ian Keen, David Johnston, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Diane Smith, Elspeth Young. Correspondents Jeremy Beckett, Valerie Chapman, Ian Clark, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ronald Lampert, Campbell Macknight, Ewan Morris, John Mulvaney, Andrew Markus, Bob Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Roser, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Shaw, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia will be welcomed. Issues include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Editors 1997 Rob Paton and Di Smith, Editors, Luise Hercus, Review Editor and Ian Howie Willis, Managing Editor. Aboriginal History Monograph Series Published occasionally, the monographs present longer discussions or a series of articles on single subjects of contemporary interest. Previous monograph titles are D. Barwick, M. Mace and T. Stannage (eds), Handbook of Aboriginal and Islander History; Diane Bell and Pam Ditton, Law: the old the nexo; Peter Sutton, Country: Aboriginal boundaries and land ownership in Australia; Link-Up (NSW) and Tikka Wilson, In the Best Interest of the Child? Stolen children: Aboriginal pain/white shame, Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus, History in Portraits: biographies of nineteenth century South Australian Aboriginal people. -

Brothers Under Arms, the Tasmanian Volunteers

[An earlier version was presented to Linford Lodge of Research. The improved version, below, was to have been presented to the Discovery Lodge of Research on 6 September 2012, but, owing to illness of the author, was simply published in the Transactions of Discovery Lodge in October 2012.] Brothers under Arms, the Tasmanian Volunteers by Bro Tony Pope Introduction For most of my life, as a newspaper reporter, police officer, and Masonic researcher, I have been guided by the advice of that sage old journalist, Bro Rudyard Kipling:1 I keep six honest serving men (They taught me all I knew); Their names are What and Why and When And How and Where and Who. But this paper is experimental, in that I have also taken heed of the suggestions of three other brethren: Bro Richard Dawes, who asked the speakers at the Goulburn seminar last year to preface their talks with an account of how they set about researching and preparing their papers; Bro Bob James, who urges us to broaden the scope of our research, to present Freemasonry within its social context, and to emulate Socrates rather than Moses in our presentation; and Bro Trevor Stewart, whose advice is contained in the paper published in the July Transactions, ‘The curious case of Brother Gustav Petrie’. Tasmania 1995 Rudyard Kipling Richard Dawes Bob James Trevor Stewart I confess that I have not the slightest idea how to employ the Socratic method in covering my chosen subject, and I have not strained my brain to formulate Bro Stewart’s ‘third order or philosophical’ questions, but within those limitations this paper is offered as an honest attempt to incorporate the advice of these brethren. -

L'ton Thematic History Report

LAUNCESTON HERITAGE STUDY STAGE 1: THEMATIC HISTORY Prepared by Ian Terry & Nathalie Servant for Launceston City Council July 2002 © Launceston City Council Cover. Launceston in the mid nineteenth century (Sarah Ann Fogg, Launceston: Tamar Street Bridge area , Allport Library & Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania). C O N T E N T S The Study Area ........................................................................................................................1 The Study .................................................................................................................................2 Authorship................................................................................................................................2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................2 Acknowledgments....................................................................................................................3 Abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................3 HISTORIC CONTEXT Introduction..............................................................................................................................4 1 Environmental Context .........................................................................................................5 2 Human Settlement.................................................................................................................6 -

Women in Colonial Commerce 1817-1820: the Window of Understanding Provided by the Bank of New South Wales Ledger and Minute Books

WOMEN IN COLONIAL COMMERCE 1817-1820: THE WINDOW OF UNDERSTANDING PROVIDED BY THE BANK OF NEW SOUTH WALES LEDGER AND MINUTE BOOKS Leanne Johns A thesis presented for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the Australian National University, Canberra August 2001 DECLARATION I certify that this thesis is my own work. To the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any material previously published or written by another person where due reference is not made in the text. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge a huge debt of gratitude to my principal supervisor, Professor Russell Craig, for his inspiration and encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. He gave insightful and expert advice, reassurance when I needed it most, and above all, never lost faith in me. Few supervisors can have been so generous with their time and so unfailing in their support. I also thank sincerely Professor Simon Ville and Dr. Sarah Jenkins for their measured and sage advice. It always came at the right point in the thesis and often helped me through a difficult patch. Westpac Historical Services archivists were extremely positive and supportive of my task. I am grateful to them for the assistance they so generously gave and for allowing me to peruse and handle their priceless treasures. This thesis would not have been possible without their cooperation. To my family, who were ever enthusiastic about my project and who always encouraged and championed me, I offer my thanks and my love. Finally, this thesis is dedicated to the thousands of colonial women who endured privations, sufferings and loneliness with indomitable courage. -

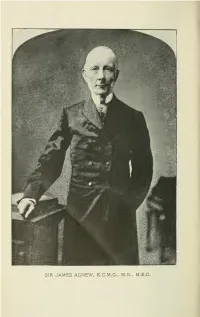

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©Bititarn*

SIR JAMES AGNEW, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.G. ©bititarn* Sir James Wilson Agnew, K.C.M.G., M.D., M.E.C., Senior Vice-President of the Royal Society of Tas- mania. Died on cSth November, 1901, in the 87th year of his age. —Born at Ballyclare, Ireland, on the 2nd October, 1815, he studied for the medical profession in London and Paris, and at Glas^^-ow, where he graduated M.D., as his father and grandfather had done before him, and came to Australia in 1839. After a short stay in New South Wales and Victoria (then known as Port Phillip), he accepted from Sir John Franklin the offer of appointment as medical officer to an important station at Tasman's Peninsula, wliere he devoted the greater part of his leisure time to the study of natural history. Prior to his removal to Hobart for the more extended practice of his profession, in which he sub- sequently attained a position of acknowledged eminence, he had assisted in founding the Tasmanian Societ}^, and lie became an active member of the Royal Society, into which the former Society merged in 1844. Shortly after the retirement of Dr. Milligan, its Secretary and Curator, in 1860, he undertook the duties of Seci'etary as a labour of love, in order that the whole of the limited amount available out of income might be appropriated as salary for the Curator of the Museum. From that time on- wards, except during occasional periods of absence from Tasmania, he continued to act as chief executive officer of the Royal Society in the capacity of Honorary Secretary for many years, and latterly in that of Chairman of the Council ; and to the admirable manner in which those self-imposed duties were discharo-ed. -

Development of Tasmanian Water Right Legislation 1877-1885: a Tortuous Process

Journal of Australasian Mining History, Vol. 15, 2017 Development of Tasmanian water right legislation 1877-1885: a tortuous process By KEITH PRESTON rior to the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, a right to water was governed by the riparian doctrine, a common law principle of entitlement that was established P in Great Britain during the 15th and 16th centuries.1 Water entitlements were tied to land ownership whereby the occupant could access a watercourse flowing through a landholding or along its boundary. This doctrine was introduced to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land in 1828 with the passing of the Australian Courts Act (9 Geo. No. 4) that transferred ‘all laws and statutes in force in the realm of England’.2 The riparian doctrine became part of New South Wales common law following a Supreme Court ruling in 1859.3 During the Californian and Victorian gold rushes, the principle of prior appropriation was established to protect the rights of mining leaseholders on crown land but riparian rights were retained for other users, particularly for irrigation of private land. The principle of prior appropriation was based on first possession, which established priority when later users obtained water from a common source, although these rights could be traded and were a valuable asset in the regulation of water supply to competing claims on mining fields.4 In Tasmania, disputes over water rights between 1881-85 challenged the application of these two doctrines, forcing repeated revision of legislation. The Tasmanian Parliament passed the first gold mining legislation in September 1859, eight years after the first gold rushes in Victoria and New South Wales, which marked the widespread introduction of alluvial mining in Australia.