The Ethno-Politics of Water Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

Esta Propuesta Legislativa Busca Llenar Un Vacío Legal... El Señor PRESIDENTE (Luis Gonzales Po- Sada Eyzaguirre).— Disculpe

1064 Diario de los Debates - PRIMERA LEGISLATURA ORDINARIA DE 2007 - TOMO II Esta propuesta legislativa busca llenar un vacío Se deja constancia del voto a favor de los congre- legal... sistas Rebaza Martell, Peralta Cruz, Beteta Ru- bín, Maslucán Culqui y Otárola Peñaranda. El señor PRESIDENTE (Luis Gonzales Po- sada Eyzaguirre).— Disculpe, congresista. “Votación para exonerar de segunda votación el texto sustitutorio del Le estábamos dando el uso de la palabra para Proyecto N.° 911 que pudiera solicitar que se exonere de segunda votación el proyecto de ley que acabamos de apro- Señores congresistas que votaron a favor: bar de manera abrumadora. Abugattás Majluf, Alegría Pastor, Anaya Oropeza, Andrade Carmona, Balta Salazar, Bruce Montes La señora CHACÓN DE VETTO- de Oca, Cajahuanca Rosales, Calderón Castro, RI (GPF).— Señor Presidente, no Carpio Guerrero, Carrasco Távara, Cenzano he solicitado exoneración de segun- Sierralta, Eguren Neuenschwander, Espinoza da votación. Ramos, Estrada Choque, Falla Lamadrid, Flores Torres, Galindo Sandoval, Guevara Trelles, Seguiremos el Reglamento, señor Herrera Pumayauli, Huancahuari Páucar, Huerta Presidente. Díaz, Lazo Ríos de Hornung, León Minaya, León Zapata, Luizar Obregón, Macedo Sánchez, El señor PRESIDENTE (Luis Gonzales Po- Mayorga Miranda, Mendoza del Solar, Nájar sada Eyzaguirre).— Correcto. Kokally, Negreiros Criado, Núñez Román, Peña Angulo, Pérez del Solar Cuculiza, Perry Cruz, Puede hacer uso de la palabra el congresista Ramos Prudencio, Reymundo Mercado, Robles Oswaldo Luizar. López, Rodríguez Zavaleta, Ruiz Delgado, Ruiz Silva, Salazar Leguía, Saldaña Tovar, Sánchez El señor LUIZAR OBREGÓN Ortiz, Sasieta Morales, Serna Guzmán, Silva Díaz, (N-UPP).— Presidente, entiendo Sucari Cari, Sumire de Conde, Supa Huamán, que la posición de la congresista Torres Caro, Urquizo Maggia, Urtecho Medina, Cecilia Chacón es la posición de su Valle Riestra González Olaechea, Vargas Fernán- bancada. -

Cio De Nuestra Nación. Lima, 30 De Noviembre De 2007

PRIMERA LEGISLATURA ORDINARIA DE 2007 - TOMO III - Diario de los Debates 1959 profesionalismo dan lo mejor de sí para benefi- “El Congreso de la República; cio de nuestra nación. Acuerda: Lima, 30 de noviembre de 2007.” Primero.— Saludar a la provincia de Tocache, “El Congreso de la República; región San Martín, con motivo de celebrar el 6 de diciembre de 2007 el Vigésimo Tercer Aniver- Acuerda: sario de su creación, además de reconocer los es- fuerzos de sus autoridades y pobladores por apro- Primero.— Expresar su saludo a todos los sol- vechar sus recursos y vivir en un clima de paz y dados del Perú, que contribuyen al desarrollo del desarrollo. país, con motivo de conmemorar el 9 de diciem- bre de 2007, el ‘Día del Ejército del Perú’. Segundo.— Transcribir la presente Moción al señor David Bazán Arévalo, Alcalde de la Muni- Segundo.— Transcribir la presente Moción al cipalidad Provincial de Tocache y, por su inter- señor General de Ejército Edwin Alberto Donayre medio, a las autoridades y población en general. Gotzch, Comandante General del Ejército del Perú y, por su intermedio, a todos los soldados Lima, 6 de diciembre de 2007.” del Ejército Peruano, con especial deferencia a la Base Militar de la Región Pasco. “El Congreso de la República; Lima, 5 de diciembre de 2007.” Acuerda: “El Congreso de la República; Primero.— Saludar a la provincia de San Mar- cos, región Cajamarca, con motivo de conmemo- Acuerda: rar el 11 de diciembre de 2007 el Vigésimo Quinto Aniversario de su creación política; circunscrip- Primero.— Expresar su saludo al Ejército del ción que en la actualidad lidera el desarrollo eco- Perú, con motivo de celebrarse el 9 de diciembre nómico y social del departamento de Cajamarca. -

Geosites and Geotouristic Attractions Proposed for the Project Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua, Peru

Geoheritage (2018) 10:707–729 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-018-0307-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Geosites and Geotouristic Attractions Proposed for the Project Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua, Peru Andrzej Gałaś1 & Andrzej Paulo1 & Krzysztof Gaidzik2,3 & Bilberto Zavala4 & Tomasz Kalicki5 & Danitza Churata4 & Slávka Gałaś1 & Jersey Mariño4 Received: 15 July 2016 /Accepted: 18 May 2018 /Published online: 7 June 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract The Colca Canyon (Central Andes, Southern Peru), about 100 km long and 1–3 km deep, forms a magnificent cross section of the Earth’s crust giving insight into mutual relations between lithostratigraphical units, and allowing relatively easy interpretation of the fascinating geological history written in the rocky beds and relief. Current activity of tectonic processes related to the subduction of the Nazca plate beneath the South American Plate exposed the geological heritage within study area. Well- developed tectonic structures present high scientific values. The volcanic landforms in the Valley of the Volcanoes and around the Colca Canyon include lava flows, scoria cones and small lava domes. They represent natural phenomena which gained recognition among tourists, scientists and local people. Studies performed by the Polish Scientific Expedition to Peru since 2003 recognized in area of Colca Canyon and Valley of the Volcanoes high geodiversity, potential for geoturism but also requirements for protectection. The idea of creating geopark gained recently the approval of regional and local authorities with support from the local National Geological Survey (INGEMMET). The Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua would strengthen the relatively poor system of the protected areas in the Arequipa department, increasing the touristic attractiveness and determine constraints for sustained regional development. -

Balance Político Normativo Sobre El Acceso De Las Y Los Adolescentes A

Balance político normativo sobre el acceso de las y los adolescentes a los servicios de salud sexual, salud reproductiva y prevención del VIH-Sida Balance político normativo sobre el acceso de las y los adolescentes a los servicios de salud sexual, salud reproductiva y prevención del VIH-Sida Ministerio de Salud del Perú Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas 2009 Edición: Instituto de Educación y Salud Equipo consultor asociado al Instituto de Educación y Salud Marcela Huaita Constantino Vila Catalina Hidalgo Alicia Quintana Cuidado de edición: Rocío Moscoso Diseño y diagramación: LuzAzul gráfica s. a. c. Impresión: El contenido de esta publicación se elaboró en el marco del plan de trabajo 2008 acordado entre el Minis- terio de Salud y el Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas. Hecho el depósito legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú N.° ___________ Los contenidos de esta publicación no reflejan necesariamente el punto de vista oficial del Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas ni del Instituto de Educación y Salud. MINSA-UNFPA. Balance político normativo sobre el acceso de las y los adolescentes a los servicios de salud sexual, salud reproductiva y prevención del VIH-Sida Lima: IES, 2009. Adolescentes, salud sexual, salud reproductiva, prevención del VIH, marco normativo, servi- cios de salud, derechos sexuales y derechos reproductivos Índice Introducción ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

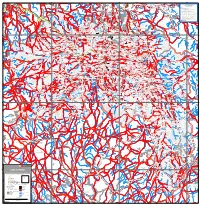

UGEL ESPINAR O Cerro Salla Lori

-71 .67 -71 .34 -71 VELILLE 617316 240494 C Soromisa Callejon Pampa 112885 e Consapata ") sa $+ Chaychapampa r a ome o 4 *# 652213 ") ro h c or 613309 *# y 0 400 o S 0 (! 210738 M c 516931 a Cerr lu 0 C Pukañan Cerro Silluta i Cerros Occorotoñe n a 0 e sa a o im C r 539319 Rosaspata # y C r r Huarcachapi / Qquellabamba a * Cerr c o o # o o Celopinco u r %, LAGO Huallataccota * Cerro Incacancha c C c Q a c a er Cerro Quirma Q 119397 *# 222362 a a Q c o p p Cerro Huacot 530275 Q a UGEL CHUMBIVILCAS l e d n C u o LANGUI l c d d r l I M m A Q Carta Educativa 2018 l i a a r a . a is Hilatunga d a C . o i n o a o CHECCA p i u *# C F C C . a h a LAYO . p r 617660 z a C d u a S L s R Sausaya u a u c e i p h r R o Q u u y c e a a c a l Q i Elaborada por la Unidad de Estadística del r e r u A i a Ccochapata y o c l n t r Cerro Mauro Moa 110101 Cerro Oquesupa n a Taypitunga t u r h i t . c am ") Exaltacion o o i Q i P a C a n d r a m 4000 e ta P 527487 Campo Villa c o a h . -

Capítulo 2: Radiografía De Los 120 Congresistas

RADIOGRAFÍA DEL CONGRESO DEL PERÚ - PERÍODO 2006-2011 capítulo 2 RADIOGRAFÍA DE LOS 120 CONGRESISTAS RADIOGRAFÍA DEL CONGRESO DEL PERÚ - PERÍODO 2006-2011 RADIOGRAFÍA DE LOS 120 CONGRESISTAS 2.1 REPRESENTACIÓN Y UBICACIÓN DE LOS CONGRESISTAS 2.1.1 Cuadros de bancadas Las 7 Bancadas (durante el período 2007-2008) GRUPO PARLAMENTARIO ESPECIAL DEMÓCRATA GRUPO PARLAMENTARIO NACIONALISTA Carlos Alberto Torres Caro Fernando Daniel Abugattás Majluf Rafael Vásquez Rodríguez Yaneth Cajahuanca Rosales Gustavo Dacio Espinoza Soto Marisol Espinoza Cruz Susana Gladis Vilca Achata Cayo César Galindo Sandoval Rocio de María González Zuñiga Juvenal Ubaldo Ordoñez Salazar Víctor Ricardo Mayorga Miranda Juana Aidé Huancahuari Páucar Wilder Augusto Ruiz Silva Fredy Rolando Otárola Peñaranda Isaac Mekler Neiman José Alfonso Maslucán Culqui Wilson Michael Urtecho Medina Miró Ruiz Delgado Cenaida Sebastiana Uribe Medina Nancy Rufina Obregón Peralta Juvenal Sabino Silva Díaz Víctor Isla Rojas Pedro Julián Santos Carpio Maria Cleofé Sumire De Conde Martha Carolina Acosta Zárate José Antonio Urquizo Maggia ALIANZA PARLAMENTARIA Hilaria Supa Huamán Werner Cabrera Campos Carlos Bruce Montes de Oca Juan David Perry Cruz Andrade Carmona Alberto Andrés GRUPO PARLAMENTARIO FUJIMORISTA Alda Mirta Lazo Ríos de Hornung Keiko Sofía Fujimori Higuchi Oswaldo de la Cruz Vásquez Yonhy Lescano Ancieta Alejandro Aurelio Aguinaga Recuenca Renzo Andrés Reggiardo Barreto Mario Fernando Peña Angúlo Carlos Fernando Raffo Arce Ricardo Pando Córdova Antonina Rosario Sasieta Morales -

Comisión Especial Multipartidaria Encargada De Estudiar Y Recomendar La Solución a La Problemática De Los Pueblos Indígenas

COMISIÓN ESPECIAL MULTIPARTIDARIA ENCARGADA DE ESTUDIAR Y RECOMENDAR LA SOLUCIÓN A LA PROBLEMÁTICA DE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS INFORME DE GESTIÓN DEL PERÍODO ANUAL DE SESIONES 2008 – 2009 Congresista Gloria Deniz Ramos Prudencio Presidenta Julio 2009 Informe de Gestión “Comisión Especial Multipartidaria Encargada de Estudiar y Recomendar la 1 Solución a la Problemática de los Pueblos Indígenas” – Período Legislativo 2008-2009 COMISIÓN MULTIPARTIDARIA ENCARGADA DE ESTUDIAR Y RECOMENDAR LA SOLUCIÓN A LA PROBLEMÁTICA INDÍGENA LEGISLATURA 2008-2009 Congresistas: Gloria Deniz Ramos Prudencio Presidenta Juan David Perry Cruz Vicepresidente Karina Juliza Beteta Rubín Secretaria Hilaria Supa Huamán Elizabeth León Minaya María Cleofé Sumire Conde Gabriela Lourdes Pérez del Solar Cuculiza Alfredo Tomás Cenzano Sierralta José Macedo Sánchez Yonhy Lescano Ancieta Rolando Reátegui Flores Eduardo Peláez Bardales Responsables de la elaboración del presente informe: Abogado Handersson Bady Casafranca Valencia Asesor Principal de la Comisión Multipartidaria Encargada de Estudiar y Recomendar la Solución a la Problemática Indígena. Antropóloga Yndira Aguirre Valdyglesias Asesora de la Comisión Multipartidaria Encargada de Estudiar y Recomendar la Solución a la Problemática Indígena. Técnica Parlamentaria: María Gutiérrez Delgado Secretaria de la Comisión Multipartidaria Encargada de Estudiar y Recomendar la Solución a la Problemática Indígena. Congreso de la República Lima – Perú – Julio de 2009 Informe de Gestión “Comisión Especial Multipartidaria Encargada -

Comprender La Agricultura En Los Andes Peruanos: Religión En La Comunidad De Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa)

Comprender la agricultura en los Andes Peruanos: Religión en la comunidad de Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa) Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/article Authors Sánchez Dávila, Mario Elmer Publisher Centro de Estudios Antropológicos Luis Eduardo Valcárcel Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess Download date 02/10/2021 15:30:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/622562 Comprender la agricultura en los Andes Peruanos: Religión en la comunidad de Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa) Understanding agriculture in the Peruvian Andes: Religión in the community of Yanque (Caylloma, Arequipa) MARIO E. SÁNCHEZ DÁVILA1 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP) Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) [email protected] Recibido: 04 de julio de 2017 Aceptado: 01 de septiembre de 2017 Resumen Este artículo analiza la agricultura en el mundo Andino a través del caso la comunidad de Yanque, distrito de la provincia de Caylloma, departamento de Arequipa (Perú). La agricultura es su principal actividad social debido a la importancia colectiva no sólo de sus manifestaciones económicas y políticas, sino también religiosas. Por eso, este artículo se enfoca en las expresiones religiosas más visibles: el sincretismo católico-quechua y la fiesta laboral ritualizada del Yarqa Aspiy. Palabras clave: andes, agricultura, religión, Perú Abstract This paper analyzes agriculture in the Andean world through the case of the community of Yanque, district of Caylloma province, department of Arequipa (Perú). Agriculture comes to have an organizing force in this community not only for its economic and political effects, but also for its religious dimensions. For this reason, this paper focuses on one of the community’s most visible religious expressions: the Yarqa Aspiy, describing the ways in which this festival ritualizes labor in performances of Catholic-Quechua syncretism. -

INDIGENOUS LIFE PROJECTS and EXTRACTIVISM Ethnographies from South America Edited by CECILIE VINDAL ØDEGAARD and JUAN JAVIER RIVERA ANDÍA

INDIGENOUS LIFE PROJECTS AND EXTRACTIVISM Ethnographies from South America Edited by CECILIE VINDAL ØDEGAARD and JUAN JAVIER RIVERA ANDÍA APPROACHES TO SOCIAL INEQUALITY AND DIFFERENCE Approaches to Social Inequality and Difference Series Editors Edvard Hviding University of Bergen Bergen, Norway Synnøve Bendixsen University of Bergen Bergen, Norway The book series contributes a wealth of new perspectives aiming to denaturalize ongoing social, economic and cultural trends such as the processes of ‘crimigration’ and racialization, fast-growing social-economic inequalities, depoliticization or technologization of policy, and simultaneously a politicization of difference. By treating naturalization simultaneously as a phenomenon in the world, and as a rudimentary analytical concept for further development and theoretical diversification, we identify a shared point of departure for all volumes in this series, in a search to analyze how difference is produced, governed and reconfigured in a rapidly changing world. By theorizing rich, globally comparative ethnographic materials on how racial/cultural/civilization differences are currently specified and naturalized, the series will throw new light on crucial links between differences, whether biologized and culturalized, and various forms of ‘social inequality’ that are produced in contemporary global social and political formations. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14775 Cecilie Vindal Ødegaard Juan Javier Rivera Andía Editors Indigenous Life Projects and Extractivism Ethnographies from South America Editors Cecilie Vindal Ødegaard Juan Javier Rivera Andía University of Bergen Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Bergen, Norway Barcelona, Spain Approaches to Social Inequality and Difference ISBN 978-3-319-93434-1 ISBN 978-3-319-93435-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93435-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018954928 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. -

Final Project Report

STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES FOR DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND INCREASING RESILIENCE IN COMMUNITIES OF CAYLLOMA, AREQUIPA. FINAL PROJECT REPORT OCTOBER 2018 – DECEMBER 2019 GENERAL PROJECT INFORMATION STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES FOR DISASTER RISK Project Title REDUCTION AND INCREASING RESILIENCE IN COMMUNITIES OF CAYLLOMA, AREQUIPA. Award number 72OFDA18GR00319 Registration number REQ-OFDA-18-000751 Start date October 01, 2018 Duration 15 months Country / region: Peru / department of Arequipa, province of Caylloma. Reported period: October 2018 – December 2019 Date of report: February 21, 2020 Adventist Development and Relief Agency International - ADRA INTERNATIONAL Report for: Debra Olson, Program Manager, Program Implementation Unit. Nestor Mogollon, Director of Monitoring and Evaluation. Adventist Development and Relief Agency Perú – ADRA Perú Víctor Huamán, Project Manager. Report by: cell phone: 51 - 997 555 483 - email: [email protected] Erick Quispe, Project Field Coordinator. cell phone: 51 - 966 315 430 - email: [email protected] REPORTE ANUAL: OCTUBRE 2018 – SETIEMBRE 2019 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since 2016, the Sabancaya volcano has registered permanent eruptive activity with gas, ash and earthquake emissions, which together with other natural events such as earthquakes, frost, intense rains and landslides interrupt local development and affect thousands of people in the Caylloma province. For this reason, the project aimed to integrate disaster risk management into institutional management tools of local governments in the Caylloma Province, with the participation of the population and collaboration at the regional and national levels. The project " Allichakusun ante desastres" (“Preparing ourselves for disasters”) began in October 2018 and ended in December 2019. It executed 100% of the financing received from USAID, also achieving an income of S/. -

Informe Sobre Los Decretos Legislativos Vinculados a Los Pueblos Indígenas Promulgados Por El Poder Ejecutivo En Mérito a La Ley N° 29157

COMISIÓN MULTIPARTIDARIA ENCARGADA DE ESTUDIAR Y RECOMENDAR LA SOLUCIÓN A LA PROBLEMÁTICA DE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS PERIODO LEGISLATIVO 2008 2009 INFORME SOBRE LOS DECRETOS LEGISLATIVOS VINCULADOS A LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS PROMULGADOS POR EL PODER EJECUTIVO EN MÉRITO A LA LEY N° 29157 DICIEMBRE 2008 INFORME SOBRE LOS DECRETOS LEGISLATIVOS VINCULADOS A LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS PROMULGADOS POR EL PODER EJECUTIVO EN MÉRITO A LA LEY N° 29157 DICIEMBRE 2008 2 COMISIÓN MULTIPARTIDARIA ENCARGADA DE ESTUDIAR Y RECOMENDAR LA SOLUCIÓN A LA PROBLEMÁTICA INDÍGENA LEGISLATURA 2008-2009 Congresistas: Gloria Deniz Ramos Prudencio Presidenta Juan David Perry Cruz Vicepresidente Karina Beteta Rubín Secretaria Hilaria Supa Huamán María Sumire Conde Elizabeth León Minaya Gabriela Pérez del Solar Cuculiza José Macedo Sánchez Alfredo Cenzano Sierralta Yonhy Lescano Ancieta Aurelio Pastor Valdivieso Rolando Reátegui Flores Responsable de la elaboración del presente informe: Abogado Handersson Bady Casafranca Valencia Asesor de la Comisión Multipartidaria Encargada de Estudiar y Recomendar la Solución a la Problemática Indígena. Técnica Parlamentaria: María Gutiérrez Delgado Secretaria de la Comisión Multipartidaria Encargada de Estudiar y Recomendar la Solución a la Problemática Indígena. Congreso de la República Lima – Perú – Diciembre de 2008 *Las fotografías consignadas en la carátula del presente informe fueron tomadas de la web, se agradece a sus autores. 3 CONTENIDO Resumen Ejecutivo.........................................................................................................