Chapter, We Focused on the So- Cieties of North America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. a Consideration of Tine and Labor Expenditurein the Constrijction Process at the Teotihuacan Pyramid of the Sun and the Pover

I. A CONSIDERATION OF TINE AND LABOR EXPENDITURE IN THE CONSTRIJCTION PROCESS AT THE TEOTIHUACAN PYRAMID OF THE SUN AND THE POVERTY POINT MOUND Stephen Aaberg and Jay Bonsignore 40 II. A CONSIDERATION OF TIME AND LABOR EXPENDITURE IN THE CONSTRUCTION PROCESS AT THE TEOTIHUACAN PYRAMID OF THE SUN AND THE POVERTY POINT 14)UND Stephen Aaberg and Jay Bonsignore INTRODUCT ION In considering the subject of prehistoric earthmoving and the construction of monuments associated with it, there are many variables for which some sort of control must be achieved before any feasible demographic features related to the labor involved in such construction can be derived. Many of the variables that must be considered can be given support only through certain fundamental assumptions based upon observations of related extant phenomena. Many of these observations are contained in the ethnographic record of aboriginal cultures of the world whose activities and subsistence patterns are more closely related to the prehistoric cultures of a particular area. In other instances, support can be gathered from observations of current manual labor related to earth moving since the prehistoric constructions were accomplished manually by a human labor force. The material herein will present alternative ways of arriving at the represented phenomena. What is inherently important in considering these data is the element of cultural organization involved in such activities. One need only look at sites such as the Valley of the Kings and the great pyramids of Egypt, Teotihuacan, La Venta and Chichen Itza in Mexico, the Cahokia mound group in Illinois, and other such sites to realize that considerable time, effort and organization were required. -

Social Studies

SOCIAL STUDIES POVERTY POINT EARTHWORKS: GRADES 5-8 LOUISIANAS ANCIENT INHABITANTS (LESSON 2) GEORGE DURRETT TIME ALLOTMENT: STANDARDS: One 45-minute class periods United States History Standards for grades 5-12 This lesson can be used in conjunction withLesson http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/nchs/standards/ 1: Poverty Point Earthworks: Evolutionary worldera1.html Milestones of the Americas, or separately. If used http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/nchs/standards/ in conjunction with the first lesson, the Poverty Point worldera2.html film need not be shown again. The time allotment Standard 1A: Analyze how the natural environments would be one 45-minute class period. of the Tigris-Euphrates, Nile, and Indus valleys shaped the early development of civilization. OVERVIEW: Standard 1B: Analyze how the natural environments of the Tigris-Euphrates, Nile, and Indus valleys When we think of ancient cultures in the New World, shaped the early development of civilization. the Mayans, Aztecs, and Incas come to mind. Yet here Standard 2B: Compare the climate and geography of in Louisiana lies evidence of a culture that extends back the Huang He (Yellow River) valley with the as far as 1350 BC. The prehistoric people of Poverty natural environments of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Point created an earthen structure so immense that it and the Indus valley. was unrecognizable from the ground. In the 1950’s, an aerial photograph was discovered that pictured huge Louisiana Social Studies Content Standards earthen ridges and mounds that were not a product of http://www.doe.state.la.us/DOE/asps/home.asp natural geological formation. Geography: Physical and Cultural Systems Through the activities in this lesson, students will Students develop a spatial understanding of Earth’s examine the structures and artifacts of Poverty Point in surface and the processes that shape it, the order to understand the cultural aspects of North connections between people and places, and the American prehistoric people, their development in relationship between man and his environment. -

Visualizing Paleoindian and Archaic Mobility in the Ohio

VISUALIZING PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC MOBILITY IN THE OHIO REGION OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Amanda N. Colucci May 2017 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Dissertation written by Amanda N. Colucci B.A., Western State Colorado University, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by Dr. Mandy Munro-Stasiuk, Ph.D., Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Mark Seeman, Ph.D., Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Eric Shook, Ph.D., Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. James Tyner, Ph.D. Dr. Richard Meindl, Ph.D. Dr. Alison Smith, Ph.D. Accepted by Dr. Scott Sheridan, Ph.D., Chair, Department of Geography Dr. James Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ……………………………………………………………………………..……...……. III LIST OF FIGURES ….………………………………………......………………………………..…….…..………iv LIST OF TABLES ……………………………………………………………….……………..……………………x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..………………………….……………………………..…………….………..………xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 STUDY AREA AND TIMEFRAME ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1.1 Paleoindian Period ............................................................................................................................... -

Further Investigations Into the King George

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22) Harry Gene Brignac Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Brignac Jr, Harry Gene, "Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22)" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2720. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE KING GEORGE ISLAND MOUNDS SITE (16LV22) A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Geography and Anthropology By Harry Gene Brignac Jr. B.A. Louisiana State University, 2003 May, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to give thanks to God for surrounding me with the people in my life who have guided and supported me in this and all of my endeavors. I have to express my greatest appreciation to Dr. Rebecca Saunders for her professional guidance during this entire process, and for her inspiration and constant motivation for me to become the best archaeologist I can be. -

Archaeologist Volume 44 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 44 NO. 1 WINTER 1994 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $17.50; husband and wife (one copy of publication) $18.50; Life membership $300.00. EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included in 1994 President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an incor Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 porated non-profit organization. 1994 Vice President Stephen J. Parker, 1859 Frank Drive, BACK ISSUES Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-6642 1994 Exec. Sect. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: 43130, (614)653-9477 Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 add $1.50 P-H SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse.$20.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, 1980's& 1990's $ 6.00 add $1.50 P-H OH 43068, (614) 861-0673 1970's $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH 1960's $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43064, (614)873-5471 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are gen 1994 Immediate Past Pres. -

The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture

9 The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture A Cosmological Expression Anna Sofaer TUDIES BY THE SOLSTICE PROJECT indicate that the solar-and-lunar regional pattern that is symmetri- Smajor buildings of the ancient Chacoan culture cally ordered about Chaco Canyon’s central com- of New Mexico contain solar and lunar cosmology plex of large ceremonial buildings (Sofaer, Sinclair, in three separate articulations: their orientations, and Williams 1987). These findings suggest a cos- internal geometry, and geographic interrelation- mological purpose motivating and directing the ships were developed in relationship to the cycles construction and the orientation, internal geome- of the sun and moon. try, and interrelationships of the primary Chacoan From approximately 900 to 1130, the Chacoan architecture. society, a prehistoric Pueblo culture, constructed This essay presents a synthesis of the results of numerous multistoried buildings and extensive several studies by the Solstice Project between 1984 roads throughout the eighty thousand square kilo- and 1997 and hypotheses about the conceptual meters of the arid San Juan Basin of northwestern and symbolic meaning of the Chacoan astronomi- New Mexico (Cordell 1984; Lekson et al. 1988; cal achievements. For certain details of Solstice Pro- Marshall et al. 1979; Vivian 1990) (Figure 9.1). ject studies, the reader is referred to several earlier Evidence suggests that expressions of the Chacoan published papers.1 culture extended over a region two to four times the size of the San Juan Basin (Fowler and Stein Background 1992; Lekson et al. 1988). Chaco Canyon, where most of the largest buildings were constructed, was The Chacoan buildings were of a huge scale and the center of the culture (Figures 9.2 and 9.3). -

Ancient Maize from Chacoan Great Houses: Where Was It Grown?

Ancient maize from Chacoan great houses: Where was it grown? Larry Benson*†, Linda Cordell‡, Kirk Vincent*, Howard Taylor*, John Stein§, G. Lang Farmer¶, and Kiyoto Futaʈ *U.S. Geological Survey, Boulder, CO 80303; ‡University Museum and ¶Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; §Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department, Chaco Protection Sites Program, P.O. Box 2469, Window Rock, AZ 86515; and ʈU.S. Geological Survey, MS 963, Denver Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225 Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved August 26, 2003 (received for review August 8, 2003) In this article, we compare chemical (87Sr͞86Sr and elemental) analyses of archaeological maize from dated contexts within Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, to potential agricul- tural sites on the periphery of the San Juan Basin. The oldest maize analyzed from Pueblo Bonito probably was grown in an area located 80 km to the west at the base of the Chuska Mountains. The youngest maize came from the San Juan or Animas river flood- plains 90 km to the north. This article demonstrates that maize, a dietary staple of southwestern Native Americans, was transported over considerable distances in pre-Columbian times, a finding fundamental to understanding the organization of pre-Columbian southwestern societies. In addition, this article provides support for the hypothesis that major construction events in Chaco Canyon were made possible because maize was brought in to support extra-local labor forces. etween the 9th and 12th centuries anno Domini (A.D.), BChaco Canyon, located near the middle of the high-desert San Juan Basin of north-central New Mexico (Fig. -

State Parks and Early Woodland Cultures

State Parks and Early Woodland Cultures Key Objectives State Parks Featured Students will understand some basic information related to the ■ Mounds State Park www.in.gov/dnr/parklake/2977.htm Adena, Hopewell and early Woodland Indians, and their connec- ■ Falls of the Ohio State Park www.in.gov/dnr/parklake/2984.htm tions to Mounds and Falls of the Ohio state parks. The students will gain insight into the connection between the Adena culture and the Hopewell tradition, and learn how archaeologists have studied artifacts and mounds to understand these cultures. Activity: Standards: Benchmarks: Assessment Tasks: Key Concepts: Mounds Students will research what was import- Artifacts Identify and compare the major early cultures ant to the Adena Indians. The students Tribes Researching SS.4.1.1 that existed in the region that became Indiana will then compile a list of items found in Adena the Past before contact with Europeans. the Adena mounds and compare them to Hopewell items that we use today. Mississippians Identify and describe historic Native American Use computers in a cooperative group groups that lived in Indiana before the time of to create timelines of major events from SS.4.1.2 early European exploration, including ways that the era of the Adena to the rise of the the groups adapted to and interacted with the Hopewell Indians. physical environment. Use computers in a cooperative group Create and interpret timelines that show rela- to create timelines of major events from SS.4.1.15 tionships among people, events and movements the era of the Adena to the rise of the in the history of Indiana. -

Interpretation and Visitor Experience at Chaco Culture National Historic Park Maren Else Svare

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Anthropology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2015 Speaking in Circles: Interpretation and Visitor Experience at Chaco Culture National Historic Park Maren Else Svare Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Svare, Maren Else. "Speaking in Circles: Interpretation and Visitor Experience at Chaco Culture National Historic Park." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds/69 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maren Else Svare Candidate Anthropology Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Dr. Ronda Brulotte, Chairperson Dr. Erin Debenport Dr. Loa Traxler i SPEAKING IN CIRCLES: INTERPRETATION AND VISITOR EXPERIENCE AT CHACO CULTURE NATIONAL HISTORIC PARK by MAREN ELSE SVARE BACHELOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Anthropology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2015 ii Acknowledgments This thesis could have been completed without the wisdom, support, and diligence of my committee. Thank you to my committee chair, Dr. Ronda Brulotte, for consistently and patiently guiding me to rethink and rework. Dr. Erin Debenport supplied both good humor and good advice, keeping my expectations realistic and my writing on track. I am grateful to Dr. -

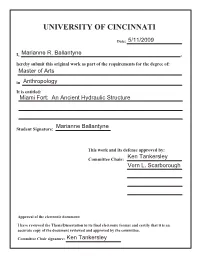

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5/11/2009 I, Marianne R. Ballantyne , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in Anthropology It is entitled: Miami Fort: An Ancient Hydraulic Structure Marianne Ballantyne Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Ken Tankersley Vern L. Scarborough Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Ken Tankersley Miami Fort: An Ancient Hydraulic Structure A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences 2009 Marianne R. Ballantyne B.A., University of Toledo 2007 Committee: Kenneth B. Tankersley, Chair Vernon L. Scarborough ABSTRACT Miami Fort, located in southwestern Ohio, is a multicomponent hilltop earthwork approximately nine kilometers in length. Detailed geological analyses demonstrate that the earthwork was a complex gravity-fed hydraulic structure, which channeled spring waters and surface runoff to sites where indigenous plants and cultigens were grown in a highly fertile but drought prone loess soil. Drill core sampling, x-ray diffractometry, high-resolution magnetic susceptibility analysis, and radiocarbon dating demonstrate that the earthwork was built after the Holocene Climatic Optimum and before the Medieval Warming Period. The results of this study suggest that these and perhaps other southern Ohio hilltop earthworks are hydraulic structures rather than fortifications. -

ROCK PAINTINGS at HUECO TANKS STATE HISTORIC SITE by Kay Sutherland, Ph.D

PWD BK P4501-095E Hueco 6/22/06 9:06 AM Page A ROCK PAINTINGS AT HUECO TANKS STATE HISTORIC SITE by Kay Sutherland, Ph.D. PWD BK P4501-095E Hueco 6/22/06 9:06 AM Page B Mescalero Apache design, circa 1800 A.D., part of a rock painting depicting white dancing figures. Unless otherwise indicated, the illustrations are photographs of watercolors by Forrest Kirkland, reproduced courtesy of Texas Memorial Museum. The watercolors were photographed by Rod Florence. Editor: Georg Zappler Art Direction: Pris Martin PWD BK P4501-095E Hueco 6/22/06 9:06 AM Page C ROCK PAINTINGS AT HUECO TANKS STATE HISTORIC SITE by Kay Sutherland, Ph.D. Watercolors by Forrest Kirkland Dedicated to Forrest and Lula Kirkland PWD BK P4501-095E Hueco 6/22/06 9:06 AM Page 1 INTRODUCTION The rock paintings at Hueco Tanks the “Jornada Mogollon”) lived in State Historic Site are the impres- small villages or pueblos at and sive artistic legacy of the different near Hueco Tanks and painted on prehistoric peoples who found the rock-shelter walls. Still later, water, shelter and food at this the Mescalero Apaches and possibly stone oasis in the desert. Over other Plains Indian groups 3000 paintings depict religious painted pictures of their rituals masks, caricature faces, complex and depicted their contact with geometric designs, dancing figures, Spaniards, Mexicans and Anglos. people with elaborate headdresses, The European newcomers and birds, jaguars, deer and symbols settlers left no pictures, but some of rain, lightning and corn. Hidden chose instead to record their within shelters, crevices and caves names with dates on the rock among the three massive outcrops walls, perhaps as a sign of the of boulders found in the park, the importance of the individual in art work is rich in symbolism and western cultures. -

Chaco Culture

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Chaco Culture Chaco Culture N.H.P. Chaco Canyon Place Names In 1849, Lieutenant James Simpson, a member of the Washington Expedition, surveyed many areas throughout the Southwest. He described and reported on many ancestral Puebloan and Navajo archaeological sites now associated with Chaco Culture NHP. Simpson used the names given to him by Carravahal, a local guide, for many of the sites. These are the names that we use today. However, the Pueblo Peoples of NM, the Hopi of AZ, and the Navajo, have their own names for many of these places. Some of these names have been omitted due to their sacred and non-public nature. Many of the names listed here are Navajo since the Navajo have lived in the canyon most recently and continue to live in the area. These names often reveal how the Chacoan sites have been incorporated into the culture, history, and oral histories of the Navajo people. There are also different names for the people who lived here 1,000 years ago. The people who lived in Chaco were probably diverse groups of people. “Anasazi” is a Navajo word which translates to “ancient ones” or “ancient enemies.” Today, we refer to this group as the “Ancestral Puebloans” because many of the descendents of Chaco are the Puebloan people. However there are many groups that speak their own languages and have their own names for the ancient people here. “Ancestral Puebloans” is a general term that accounts for this. Chaco-A map drawn in 1776 by Spanish cartographer, Bernardo de Pacheco identifies this area as “Chaca” which is a Spanish colonial word commonly used to mean “a large expanse of open and unexplored land, desert, plain, or prairie.” The term “Chaca” is believed to be the origin of both the word Chacra in reference to Chacra Mesa and Chaco.