Music in Motion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Initiative Jka Peer - Reviewed Journal of Music

VOL. 01 NO. 01 APRIL 2018 MUSIC INITIATIVE JKA PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC PUBLISHED,PRINTED & OWNED BY HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, J&K CIVIL SECRETARIAT, JAMMU/SRINAGAR,J&K CONTACT NO.S: 01912542880,01942506062 www.jkhighereducation.nic.in EDITOR DR. ASGAR HASSAN SAMOON (IAS) PRINCIPAL SECRETARY HIGHER EDUCATION GOVT. OF JAMMU & KASHMIR YOOR HIGHER EDUCATION,J&K NOT FOR SALE COVER DESIGN: NAUSHAD H GA JK MUSIC INITIATIVE A PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION TO CONTRIBUTORS A soft copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the Editor of the journal in Microsoft Word le format. All the manuscripts will be blindly reviewed and published after referee's comments and nally after Editor's acceptance. To avoid delay in publication process, the papers will not be sent back to the corresponding author for proof reading. It is therefore the responsibility of the authors to send good quality papers in strict compliance with the journal guidelines. JK Music Initiative is a quarterly publication of MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Higher Education Department, Authors preparing submissions are asked to read and follow these guidelines strictly: Govt. of Jammu and Kashmir (JKHED). Length All manuscripts published herein represent Research papers should be between 3000- 6000 words long including notes, bibliography and captions to the opinion of the authors and do not reect the ofcial policy illustrations. Manuscripts must be typed in double space throughout including abstract, text, references, tables, and gures. of JKHED or institution with which the authors are afliated unless this is clearly specied. Individual authors Format are responsible for the originality and genuineness of the work Documents should be produced in MS Word, using a single font for text and headings, left hand justication only and no embedded formatting of capitals, spacing etc. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 05 August 2016 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Leante, Laura (2009) 'Urban Myth : bhangra and the dhol craze in the UK.', in Music in motion : diversity and dialogue in Europe. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 191-207. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.transcript-verlag.de/978-3-8376-1074-1/ Publisher's copyright statement: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk (revised version – November 2008) 1 “Urban myth”: bhangra and the dhol craze in the UK Bhangra is believed to have originated in western Punjab (in today’s Pakistan) as a rural male dance performed to the rhythm of the dhol, a large double-headed barrel drum, to celebrate the spring harvest. -

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

A Study of the Charismatic Movement in Portugal with Particular Reference To

A STUDY OF THE CHARISMATIC MOVEMENT IN PORTUGAL WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE FRATERNAL ASSOCIATION by FERNANDO CALDEIRA DA SILVA Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject CHURCH HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR M H MOGASHOA FEBRUARY 2006 Table of Contents Thesis: A STUDY OF THE CHARISMATIC MOVEMENT IN PORTUGAL WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE FRATERNAL ASSOCIATION Page Introduction 1 Chapter 1: A survey of the various forms of Christianity in Portugal 11 1.1 The establishment of Christianity in Spain and Portugal up to the Reformation 11 1.1.1 Establishment of Christianity in the Iberian Peninsula 12 1.1.2 Four main forces that led the people of the Iberian Peninsula to be attached to Roman Catholicism, as against any non-Roman Catholic Christian churches 14 1.1.3 Islamic influence on the Portuguese characteristic resistance to change, as related to non-Roman Catholic Christians 16 1.1.4 Involvement of the Pope in the independence of Portugal 17 1.2 Portugal and Europe from 1383 to 1822 18 1.2.1 A new era resulting from the revolution of 1383-1385 19 1.2.2 The Portuguese involvement in the crusades 21 1.2.3 Movements transforming the societies of Europe 21 1.2.4 Political, economic and socio-religious conditions in Portugal 23 1.2.4.1 The political conditions 23 1.2.4.2 The economic conditions 29 1.2.4.3 The socio-religious conditions 33 1.3 Reformation and Protestant influence in the Portuguese Empire 34 1.3.1 Signs of impact of the Reformation in Portugal -

First-Generation Historians Leaving a Mark: Yasmeen Ragab, Carmen Gutierrez, Johnna Jones, Jason Smith PAGE 2 Letter from the Chair

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign www.history.illinois.edu Spring 2020 First-Generation Historians Leaving a Mark: Yasmeen Ragab, Carmen Gutierrez, Johnna Jones, Jason Smith PAGE 2 Letter from the Chair fter twenty years in Champaign-Urbana and sixteen years as a faculty member, I became interim chair of the department in August 2019. I feel so lucky to lead Asuch an amazing group of scholars—faculty, graduate students, and undergradu- ate majors—for the next two years. I am grateful to Clare Crowston for her advice and wise counsel throughout the summer as we prepared for the transition. My faculty joins me in wishing her all the best for a productive and restorative sabbatical this year and in the new position she’ll assume in August 2020 as Associate Dean for the Humanities and Interdisci- plinary Programs in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. The dedicated staff in 309 Gregory Hall provide the support we all need to keep the department running smoothly, attending to every detail. I have relied on their expertise, experience, and professionalism as I have learned the job, and I am grateful to each of them. For the past eighteen years, Tom Bedwell, our business manager, has ensured the successful running of all aspects of departmental operations. His total commitment, professionalism, and skill as a financial manager are matched by his unflagging dedication to the welfare of each and every faculty member, student, and staff. Dawn Voyles assists Tom working effi- ciently to reserve flights for faculty, pay honoraria to visiting scholars, and process receipts. -

Mixology Shaken Or Stirred? Olive Or Onion? Martini Cocktail Sipping Is an Art Developed Over Time

Vol: XXXVI Wednesday, April 3, 2002 INSIDI: THIS WI;I;K ^ PHOTO BY SOFIA PANNO Various dancers from all the participating tribes and nations in this event; Blood Tribe, Peigan Nation and Blackfoot Nation performing a dance together. LCC celebrates flboriginal Ruiareness Day BY SOFIA PANNO president. the weather," said Gretta Old Shoes, Endeawour Staff The Rocky Lake Singers and Blood Tribe member and first-year Drummers entertained the crowd student at LCC. gathered around Centre Core with their Events such as this help both aboriginal As Lethbridge Community College traditional singing and drum playing, as and non-aboriginal communities better First Nations and Aboriginal Awareness did the exhibition dancers with their understand each other. Day commenced, the beat of the drums unique choreography. "It's very heart-warming to see students and the echoes from the singing flowed According to native peoples' culture from LCC take in our free event because through LCC's hallways on March 27, and beliefs passed down from one that's our main purpose, to share our 2002. generation to the next, song and dance is aboriginal culture," said David. "Our theme was building used to honour various members of a LCC First Nations Club members relationships," said Salene David, First tribe. Some songs honour the warriors indicate that awareness of native peoples' Nations Club member/volunteer. while others, the women of the tribe. current needs at LCC is a necessary step, According to the club's president Bill Canku Ota, an online newsletter in understanding them and their culture. Healy, the LGC First Nations Club Piita celebrating Native America explains the "We [the native peoples] have been Pawanii Learning Society is responsible Midewiwin Code for Long Life and here since the college has been opened for the organizing of this year's event. -

Record-Business-1982

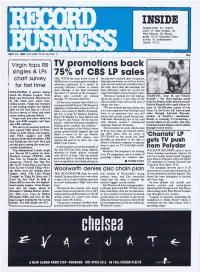

INSIDE Singles chart, 6-7; Album chart, 17; New Singles, 18; New Albums, 19; Airplay guide, 15-15; Quarterly Chart survey, 12; Independent Labels, 12/13. April 12, 1982VOLUME FIVE Number 3 65p Virgin tops RBTV promotions back singles & LPs 75% of CBS LP sales chart survey CBS, WITH the most active roster ofthe industry's national chart was gained, MOR artists, is increasingly resorting toalthough promotion on such an intense television promotion asa means ofscale was not underway anywhere else at for first time securing sufficient volume to ensurethe time. Since then the campaign has chart placings. It has been estimatedbeen efficiently rolled out to give the FOLLOWING A quarter during that about 75 percent of the company'ssinger her highest chart placing to date. which the Human League, Toni albumsalescurrentlyarecoming Television backing for the IglesiasTIGHTFIT, keepfitand Felicity Basil and Orchestral Manoeuvres through TV -boosted repertoire. album has given it a new lease of lifeKendall - the chart -topping group In The Dark were major best- after an earlier chart entry at the time offrom the Zomba stable present actress selling artists, Virgin has emerged Of the seven releases with which it is scoring in the RB Top 60, CBS has givenrelease last year. Felicity Kendall with a gold album for as the leading singles and albums "We are certainly getting volume, butsales of 200,000 -plus copies of her label for the first time in a Record significant smallscreen support to five of them, Love Songs by Barbra Streisand,it is a very expensive way of doing it andShape Up And Dance LP, sold on mail Business survey of chart and sales there is no guarantee that you willorderthroughLifestyleRecords, action during January -March. -

NASLOV Rank HAPPIER 1 NOTHING BREAKS LIKE a HEART 2 SWEET but PSYCHO 3 HIGH HOPES 4 GIANT 5 EVERYBODY's TALKIN' 5 SIJAJ 7 OB

NASLOV IZVAJALEC Rank HAPPIER MARSHMELLO & BASTILLE 1 NOTHING BREAKS LIKE A HEART MARK RONSON [+] MILEY CYRUS 2 SWEET BUT PSYCHO AVA MAX 3 HIGH HOPES PANIC AT THE DISCO 4 GIANT CALVIN HARRIS & RAG'N'BONE MAN 5 EVERYBODY'S TALKIN' BEAUTIFUL SOUTH 5 SIJAJ RAIVEN 7 OB KAVI ANABEL 8 Svet na dlani NINA PUŠLAR 9 NEKAJ JE NA TEBI NINO 10 KLIC STRAN ANABEL 10 SRCE ZA SRCE ALYA 12 RABIM TE NINO 12 WITHOUT ME HALSEY 14 LAGANO CHALLE SALLE 15 TO MI JE VŠEČ NINA PUŠLAR 15 DANCING WITH A STRANGER SAM SMITH & NORMANI 17 LOVE SOMEONE LUKAS GRAHAM 17 SEBI ZALA KRALJ & GAŠPER ŠANTL 17 NAJ MI DEZ NAPOLNI DLAN NUŠA DERENDA 17 VROČE S.I.T. 21 NOBEN ME NE RAZUME NIPKE 21 NAREDI SRCE MAJA KEUC 23 LETIM CHALLE SALLE [+] ERIK 24 LUNA NIKA ZORJAN [+] JONATAN HALLER 24 VSI VEDO LEA LIKAR 24 LETIM ŽAN SERČIČ 24 IZVEN OKVIRJA NIPKE 24 PTICA BQL 24 TA OBČUTEK DAVID DOMJANIC [+] ALEX VOLASKO [+] SAMO KOZAR 24 NI PREDAJE, NI UMIKA BQL [+] NIKA ZORJAN 31 NAZAJ ŽAN SERČIČ & GAJA PRESTOR 31 TEBE NE DAM ŽAN SERČIČ [+] LEYA 31 TVOJA EVA BOTO 31 MILIJON IN ENA KLARA JAZBEC 31 SEBE DAJEM SAMUEL LUCAS 31 PERU BQL 37 HEART OF GOLD BQL 37 ZA NAJU NINA PUŠLAR 39 ZAVEDNO EVA BOTO 39 FRIDAY I'M IN LOVE THE CURE 39 NAH NEH NAH VAYA CON DIOS 42 SHOTGUN GEORGE EZRA 43 I CAN SEE CLEARLY NOW JIMMY CLIFF 43 WHEN I DIE NO MERCY 43 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY BIG MOUNTAIN 43 WHAT LOVERS DO MAROON 5 [+] SZA 47 PROMISES CALVIN HARRIS [+] SAM SMITH 47 LOVE MY LIFE ROBBIE WILLIAMS 47 ALL I WANNA DO IS MAKE LOVE TO YOU HEART 47 FEEL IT STILL PORTUGAL THE MAN 51 FLAMES DAVID GUETTA [+] SIA 51 MEANT TO BE BEBE REXHA [+] FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE 51 LIFT ME UP GERI HALLIWELL 51 CAN'T STOP THE FEELING JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 51 MR. -

Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934-1997

ALAN LOMAX ALAN LOMAX SELECTED WRITINGS 1934–1997 Edited by Ronald D.Cohen With Introductory Essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew L.Kaye ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK • LONDON Published in 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.co.uk Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All writings and photographs by Alan Lomax are copyright © 2003 by Alan Lomax estate. The material on “Sources and Permissions” on pp. 350–51 constitutes a continuation of this copyright page. All of the writings by Alan Lomax in this book are reprinted as they originally appeared, without emendation, except for small changes to regularize spelling. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lomax, Alan, 1915–2002 [Selections] Alan Lomax : selected writings, 1934–1997 /edited by Ronald D.Cohen; with introductory essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew Kaye. -

'Race' and Diaspora: Romani Music Making in Ostrava, Czech Republic

Music, ‘Race’ and Diaspora: Romani Music Making in Ostrava, Czech Republic Melissa Wynne Elliott 2005 School of Oriental and African Studies University of London PhD ProQuest Number: 10731268 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731268 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis is a contribution towards an historically informed understanding of contemporary music making amongst Roma in Ostrava, Czech Republic. It also challenges, from a theoretical perspective, conceptions of relationships between music and discourses of ‘race’. My research is based on fieldwork conducted in Ostrava, between August 2003 and July 2004 and East Slovakia in July 2004, as well as archival research in Ostrava and Vienna. These fieldwork experiences compelled me to explore music and ideas of ‘race’ through discourses of diaspora in order to assist in conceptualising and interpreting Romani music making in Ostrava. The vast majority of Roma in Ostrava are post-World War II emigres or descendants of emigres from East Slovakia. In contemporary Ostrava, most Roma live on the socio economic margins and are most often regarded as a separate ‘race’ with a separate culture from the dominant population. -

The Taranta–Dance Ofthesacredspider

Annunziata Dellisanti THE TARANTA–DANCE OFTHESACREDSPIDER TARANTISM Tarantism is a widespread historical-religious phenomenon (‘rural’ according to De Martino) in Spain, Campania, Sardinia, Calabria and Puglia. It’s different forms shared an identical curative aim and by around the middle of the 19th century it had already begun to decline. Ever since the Middle Ages it had been thought that the victim of the bite of the tarantula (a large, non- poisonous spider) would be afflicted by an ailment with symptoms similar to those of epilepsy or hysteria. This ‘bite’ was also described as a mental disorder usually appearing at puberty, at the time of the summer solstice, and caused by the repression of physical desire, depression or unrequited love. In order to be freed from this illness, a particular ritual which included dance, music and the use of certain colours was performed. RITUAL DANCING The first written account of music as an antidote to the bite of the tarantula was given by the Jesuit scientist, Athanasius Kircher, who was also the first to notate the music and rhythm in his book Antidotum Tarantulæ in the 16th century. Among the instruments involved and used, the frame drum plays an important role together with the violin, the guitar or chitarra battente, a ten-string guitar used percussively, and the button accordion or organetto. This form of exorcism consisted in a ritual carried out in the home of the sick person and a religious ritual in the Church of San Paolo (Saint Paolo in Galatina (Lecce)) during the celebrations of the Saints Peter and Paul on the 28th June each year. -

Gossett Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Music VALUES TO VIRTUES: AN EXAMINATION OF BAND DIRECTOR PRACTICE A Dissertation in Music Education by Jason B. Gossett © 2015 Jason B. Gossett Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2015 ii The dissertation of Jason B. Gossett was reviewed and approved* by the following: Linda Thornton Associate Professor, Music Education Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Richard Bundy Professor, Music Education Davin Carr-Chellman Assistant Professor, Adult Education Joanne Rutkowski Professor, Music Education Graduate Program Chair *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation was to investigate the pedagogic values of band directors. Further, how these values are operationalized in the classroom and contribute to a director’s conception of the good life was examined. This dissertation contains the findings from three separate investigations. The purpose of the first investigation was to elicit and examine the pedagogic values of three band directors. I sought to understand their pedagogic values through observation, interviews, and examination of repertoire lists. The participants’ pedagogic values emerged as values of ends and of students. Directors identified undergraduate music education experiences, reflection, and teaching experiences as sources of their values. The purpose of my second investigation was to ascertain the values and sources of pedagogic values held by band directors and how contextual factors influence stasis or change in values. I used a descriptive survey design for this inquiry. Participants were band directors from six states representing the six National Association for Music Education regional divisions.