Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Initiative Jka Peer - Reviewed Journal of Music

VOL. 01 NO. 01 APRIL 2018 MUSIC INITIATIVE JKA PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC PUBLISHED,PRINTED & OWNED BY HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, J&K CIVIL SECRETARIAT, JAMMU/SRINAGAR,J&K CONTACT NO.S: 01912542880,01942506062 www.jkhighereducation.nic.in EDITOR DR. ASGAR HASSAN SAMOON (IAS) PRINCIPAL SECRETARY HIGHER EDUCATION GOVT. OF JAMMU & KASHMIR YOOR HIGHER EDUCATION,J&K NOT FOR SALE COVER DESIGN: NAUSHAD H GA JK MUSIC INITIATIVE A PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION TO CONTRIBUTORS A soft copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the Editor of the journal in Microsoft Word le format. All the manuscripts will be blindly reviewed and published after referee's comments and nally after Editor's acceptance. To avoid delay in publication process, the papers will not be sent back to the corresponding author for proof reading. It is therefore the responsibility of the authors to send good quality papers in strict compliance with the journal guidelines. JK Music Initiative is a quarterly publication of MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Higher Education Department, Authors preparing submissions are asked to read and follow these guidelines strictly: Govt. of Jammu and Kashmir (JKHED). Length All manuscripts published herein represent Research papers should be between 3000- 6000 words long including notes, bibliography and captions to the opinion of the authors and do not reect the ofcial policy illustrations. Manuscripts must be typed in double space throughout including abstract, text, references, tables, and gures. of JKHED or institution with which the authors are afliated unless this is clearly specied. Individual authors Format are responsible for the originality and genuineness of the work Documents should be produced in MS Word, using a single font for text and headings, left hand justication only and no embedded formatting of capitals, spacing etc. -

Jane Cornwell Speaks to Simon Emmerson, One of the Original Co-Founders of Afro Celt Sound System, and Fellow Member Johnny

AFRO CELT SOUND SYSTEM quarter of a century ago in Dakar, Senegal, a “It was frustrating,” confesses Emmerson, “going onstage respected British producer, guitarist and self- and playing the same set over and over again. My mates were described “East End New Age lager lout” stood like, ‘Hey, it’s good to see you reliving the spirit of the 90s!’ I recording a West African melody that sounded, to felt like we’d become a nostalgia band.” Bringing it Back Ahis ears, just like a traditional Irish air. Convinced there was ACSS had always been a supergroup whose line-up more to this than mere coincidence, he set in motion a chain expanded and evolved around its four core members (for Jane Cornwell speaks to Simon Emmerson, one of the original of events that would culminate in over one-and-a-half million years, Emmerson, Irish sean nós singer Iarla Ó’Lionáird, Irish album sales, two Grammy nominations, several world tours bodhrán and whistle player James McNally and engineer/ co-founders of Afro Celt Sound System, and fellow member Johnny and a couple of A-list film soundtracks. And it ain’t over yet. programmer Martin Russell), with artists ranging from Peter Kalsi about their long-awaited return to the studio and stage Last month a new, reinvigorated Afro Celt Sound System Gabriel and Robert Plant to Sinéad O’Connor and Mundy gi!ed us !e Source, their first album in a decade. It’s a work guesting on di$erent albums. that comes full circle, being as fluid and organic as their 1996 While a 20th anniversary album of new material was long debut, Volume 1: Sound Magic, and bigging up the African in the o%ng, various wildly successful projects by individual side of their migh" Afro-Celtic collaborations, as their debut members made getting together tricky. -

Lotus Infuses Downtown Bloomington with Global

FOR MORE INFORMATION: [email protected] || 812-336-6599 || lotusfest.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 8/26/2016 LOTUS INFUSES DOWNTOWN BLOOMINGTON WITH GLOBAL MUSIC Over 30 international artists come together in Bloomington, Indiana, for the 23rd annual Lotus World Music & Arts Festival. – COMPLETE EVENT DETAILS – Bloomington, Indiana: The Lotus World Music & Arts Festival returns to Bloomington, Indiana, September 15-18. Over 30 international artists from six continents and 20 countries take the stage in eight downtown venues including boisterous, pavement-quaking, outdoor dance tents, contemplative church venues, and historic theaters. Representing countries from A (Argentina) to Z (Zimbabwe), when Lotus performers come together for the four-day festival, Bloomington’s streets fill with palpable energy and an eclectic blend of global sound and spectacle. Through music, dance, art, and food, Lotus embraces and celebrates cultural diversity. The 2016 Lotus World Music & Arts Festival lineup includes artists from as far away as Finland, Sudan, Ghana, Lithuania, Mongolia, Ireland, Columbia, Sweden, India, and Israel….to as nearby as Virginia, Vermont, and Indiana. Music genres vary from traditional and folk, to electronic dance music, hip- hop-inflected swing, reggae, tamburitza, African retro-pop, and several uniquely branded fusions. Though US music fans may not yet recognize many names from the Lotus lineup, Lotus is known for helping to debut world artists into the US scene. Many 2016 Lotus artists have recently been recognized in both -

Representation Through Music in a Non-Parliamentary Nation

MEDIANZ ! VOL 15, NO 1 ! 2015 DOI: 10.11157/medianz-vol15iss1id8 - ARTICLE - Re-Establishing Britishness / Englishness: Representation Through Music in a non-Parliamentary Nation Robert Burns Abstract The absence of a contemporary English identity distinct from right wing political elements has reinforced negative and apathetic perceptions of English folk culture and tradition among populist media. Negative perceptions such as these have to some extent been countered by the emergence of a post–progressive rock–orientated English folk–protest style that has enabled new folk music fusions to establish themselves in a populist performance medium that attracts a new folk audience. In this way, English politicised folk music has facilitated an English cultural identity that is distinct from negative social and political connotations. A significant contemporary national identity for British folk music in general therefore can be found in contemporary English folk as it is presented in a homogenous mix of popular and world music styles, despite a struggle both for and against European identity as the United Kingdom debates ‘Brexit’, the current term for its possible departure from the EU. My mother was half English and I'm half English too I'm a great big bundle of culture tied up in the red, white and blue (Billy Bragg and the Blokes 2002). When the singer and songwriter, Billy Bragg wrote the above song, England, Half English, a friend asked him whether he was being ironic. He replied ‘Do you know what, I’m not’, a statement which shocked his friends. Bragg is a social commentator, political activist and staunch socialist who is proudly English and an outspoken anti–racist, which his opponents may see as arguably diametrically opposed combination. -

Recreational Facilities Provided in Jails During the Year 2018

Additional Table – 63 Recreational facilities provided in jails during the year 2018 1. Andhra Pradesh Facilities like TV, Newspapers and Indoor games like Chess, Carrom, Shuttle, Tennikoit, etc., are provided in all the prisons in the State and telephone facility is provided to the prisoners confined in Central Prisons, District Prisons and Special Sub Jails. Yoga, Meditation, Legal Aid, Art of Living and Moral Lectures by NGOs. In addition to the above, Libraries are also available in larger prisons. Sports and Games Competitions, Literary Competitions, Cultural Activities, etc. are organized on National Holidays like Republic Day, Independence Day and Mahatma Gandhi Jayanti. 2. Arunachal Pradesh TV, Carrom Board, Chess, Ludo, Volley Ball, Badminton, etc. 3. Assam Indoor Games (Carrom, Chess, Ludo, Badminton, Playing Cards), Outdoor Games (Volley Ball, Cricket), T.V., Harmonium, Tabla, Dhole, Radio, Newspaper reading, Library, etc. 4. Bihar Television, Carrom Board, Ludo, Chess, Badminton, Kushti (Wrestling), Kabaddi, Khokho, Cricket, Football, Volleyball, Gym (Fitness Centre), Gymnasium, Yoga and Meditation. 2 Telephone booths are installed in the jails. Newspaper (Hindi, English, Urdu, Hindustan, Dainik Jagran, Prabhat Khabar, Times of India), Magazines and Library facility. Computer and Electronic type writer are provided in jail. Musical instruments like Electronic Tambura, Sitar, Banjo, Mouth Organ, Flute, Harmonium, Drum Set, Flute, Guitar, Tabla, Casio, Dholak, Jhal, Kartal, Yamaha Key Pad,Triput Set, etc. Musical programme on every Sunday. In order to upgrade recreational facilities, large size HD LED TV, Movie Projector and Projection Screen were installed in the Prisoners’ Community Hall. RSETI Rural Self Employment Training Institute Elementary Education and Adult Education In order to enrich prison library, large number of books concerning various topics such as comic stories, pictorial short stories with moral values, motivational books, stories and good books on other subjects were bought during the period. -

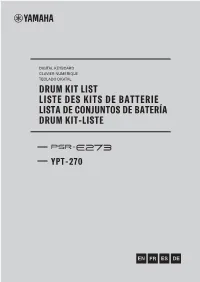

Drum Kit List

DRUM KIT LIST LISTE DES KITS DE BATTERIE LISTA DE CONJUNTOS DE BATERÍA DRUM KIT-LISTE Drum Kit List / Liste des kits de batterie/ Lista de conjuntos de batería / Drum Kit-Liste • Same as Standard Kit 1 • Comme pour Standard Kit 1 • No Sound • Absence de son • Each percussion voice uses one note. • Chaque sonorité de percussion utilise une note unique. Voice No. 117 118 119 120 121 122 Keyboard Standard Kit 1 Standard Kit 1 Indian Kit Arabic Kit SE Kit 1 SE Kit 2 Note# Note + Chinese Percussion C1 36 C 1 Seq Click H Baya ge Khaligi Clap 1 Cutting Noise 1 Phone Call C#1 37 C# 1Brush Tap Baya ke Arabic Zalgouta Open Cutting Noise 2 Door Squeak D1 38 D 1 Brush Swirl Baya ghe Khaligi Clap 2 Door Slam D#1 39 D# 1Brush Slap Baya ka Arabic Zalgouta Close String Slap Scratch Cut E1 40 E 1 Brush Tap Swirl Tabla na Arabic Hand Clap Scratch F1 41 F 1 Snare Roll Tabla tin Tabel Tak 1 Wind Chime F#1 42 F# 1Castanet Tablabaya dha Sagat 1 Telephone Ring G1 43 G 1 Snare Soft Dhol 1 Open Tabel Dom G#1 44 G# 1Sticks Dhol 1 Slap Sagat 2 A1 45 A 1 Bass Drum Soft Dhol 1 Mute Tabel Tak 2 A#1 46 A# 1 Open Rim Shot Dhol 1 Open Slap Sagat 3 B1 47 B 1 Bass Drum Hard Dhol 1 Roll Riq Tik 3 C2 48 C 2 Bass Drum Dandia Short Riq Tik 2 C#2 49 C# 2 Side Stick Dandia Long Riq Tik Hard 1 D2 50 D 2 Snare Chutki Riq Tik 1 D#2 51 D# 2 Hand Clap Chipri Riq Tik Hard 2 E2 52 E 2 Snare Tight Khanjira Open Riq Tik Hard 3 Flute Key Click Car Engine Ignition F2 53 F 2 Floor Tom L Khanjira Slap Riq Tish Car Tires Squeal F#2 54 F# 2 Hi-Hat Closed Khanjira Mute Riq Snouj 2 Car Passing -

Tabloid Nuovo TJ 05.Qxd

[email protected] 2 il festival Il segno e la musica verso la primordiale e sciamanica metafora dell’arte Il critico italiano Gianfranco Salvatore, curatore di un l’omeopatia, della cromoterapia, del soft-laser, della interessante libro sulla Techno-Trance, scrive nella sua musicoterapia), e studiosi del calibro di Bienveniste affer- prefazione: “Gli anni di techno e di musica digitale Digital Trance mano che qualsiasi sostanza agisce attraverso la sua spe- hanno risvegliato nella nostra civiltà tecnologica e cifica vibrazione, piuttosto che grazie alla sua composi- metropolitana un’antichissima risorsa vitale: la capacità zione molecolare. di trascendere il proprio corpo per accedere, attraverso la Oltre all’elemento ritmico incalzante, è dunque l’elemento musica e la danza, alla dimensione dell’ignoto, dell’al- sonoro a definire le potenzialità evocative e vibrative dello trove e dunque della trance”. tsunami sonoro che induce all’alterazione degli stati di In un recente convegno, svoltosi a Venezia nel 2002 sul coscienza. Quel flusso stratificato e circolare fatto di loops tema “Musica e stati alterati di coscienza”, si è riflettuto e campionamenti digitali che, come scrive ancora in modo approfondito sui poteri della musica che da Salvatore, “trasfigurano lo strato armonico verso uno strato sempre modificano la nostra percezione emotiva e sul- timbrico e/o di contrappunto forsennato”; ed è proprio que- l’associazione sistematica tra musica e stati transitori di sta risultanza che il musicologo Roberto Agostini definisce alterazione delle attività psichiche (trance, estasi, sdop- “contrappunto amelodico”. piamento o sovrapposizione di personalità, visione, La facilità di pilotare moderni sequencer, multieffetti digita- “viaggio” mistico, ecc.) che è riscontrabile alle più diver- li e computer con programmi di registrazione musicale, ha se latitudini e nei riti a sfondo terapeutico e religioso di facilitato enormemente quel percorso che porta a trovare molte culture e società tradizionali. -

'Racist Coup-Plotters' Jeremy Corbyn Denounces Coup Mexico Condemns

BOLIVIA: FURY AFTER ARMY ORDERS PRESIDENT OUT n Morales slams ‘racist coup-plotters’ n Jeremy Corbyn denounces coup PAGES n Mexico condemns OAS ‘silence’ 4, 7, 8-9 for Peace and Socialism £1.20 Tuesday November 12 2019 Proudly owned by our readers | Incorporating the Daily Worker | Est 1930 | morningstaronline.co.uk McDonald’s strike: ‘Join a union and improve your life’ Workers to walk out at six outlets today in demand for £15 an hour by Marcus Barnett option of having guaranteed hours of BFAWU general secretary Ronnie She also criticised McDonald’s CEO up to 40 hours a week and an end to Draper said: “McDonald’s workers are Steve Easterbrook, who was given a youth rates of pay. showing the way. “golden goodbye” in the form of a MCDONALD’S workers have said they They also want shift patterns to “They’ve challenged and defeated $42 million (£33 mil- will “stand together and win” as a be given to workers four weeks in bullying by managers. They’ve won lion) pay out strike of low-paid employees today will advance, union recognition in the changes making life at work more when he disrupt business at the corporation. workplace and the right to be treated bearable. was sacked Employees in six of the global food with respect by management, as part of “My message to every worker is this: for having chain’s London branches, who are a “New Deal” for McDonald’s workers. if you want to improve your workplace an affair members of the Bakers, Food and Numerous senior Labour figures and your life, join a union. -

Folk Instruments of Punjab

Folk Instruments of Punjab By Inderpreet Kaur Folk Instruments of Punjab Algoza Gharha Bugchu Kato Chimta Sapp Dilruba Gagar Dhadd Ektara Dhol Tumbi Khartal Sarangi Alghoza is a pair of woodwind instruments adopted by Punjabi, Sindhi, Kutchi, Rajasthani and Baloch folk musicians. It is also called Mattiyan ,Jōrhi, Pāwā Jōrhī, Do Nālī, Donāl, Girāw, Satārā or Nagōze. Bugchu (Punjabi: ਬੁਘਚੂ) is a traditional musical instrument native to the Punjab region. It is used in various cultural activities like folk music and folk dances such as bhangra, Malwai Giddha etc. It is a simple but unique instrument made of wood. Its shape is much similar to damru, an Indian musical instrument. Chimta (Punjabi: ਚਚਮਟਾ This instrument is often used in popular Punjabi folk songs, Bhangra music and the Sikh religious music known as Gurbani Kirtan. Dilruba (Punjabi: ਚਿਲਰੱਬਾ; It is a relatively young instrument, being only about 300 years old. The Dilruba (translated as robber of the heart) is found in North India, primarily Punjab, where it is used in Gurmat Sangeet and Hindustani classical music and in West Bengal. Dhadd (Punjabi: ਢੱਡ), also spelled as Dhad or Dhadh is an hourglass-shaped traditional musical instrument native to Punjab that is mainly used by the Dhadi singers. It is also used by other folk singers of the region Dhol (Hindi: ढोल, Punjabi: ਢੋਲ, can refer to any one of a number of similar types of double-headed drum widely used, with regional variations, throughout the Indian subcontinent. Its range of distribution in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan primarily includes northern areas such as the Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Kashmir, Sindh, Assam Valley Gagar (Punjabi: ਗਾਗਰ, pronounced: gāger), a metal pitcher used to store water in earlier days, is also used as a musical instrument in number of Punjabi folk songs and dances. -

Trailing of Indian Instrumental Music

International Journal of Applied Research 2017; 3(7): 145-150 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Trailing of Indian instrumental music: Performance Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2017; 3(7): 145-150 outcomes & changes www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 18-05-2017 Accepted: 20-06-2017 Dr. Abhilasha Sharma Dr. Abhilasha Sharma Assistant Professor, Abstract Department of Music The art of playing musical instruments in India were traditionally carried on from generation to Instrument, Mata Harki Devi generation, from primitive phase for this modern era. As Music is a performing art, that has been College for Women, Odhan, creative, itself, and also can't be static, thus the easy innovations as well as experiments have often Haryana, India offered fresh concepts on the contemporary generation. The content is fully intended to examine the brand new advancements in Indian Instrumental Music in the kind of testing. Music is a performing art and in this particular research inter relationship of Instrumental Experimentation and Music happens to be analysed and effect of experimentation is noted. Although, currently there continues to be huge target on testing by a lot of contemporary famous musicians, though it wasn't feasible to add in every one of them as a result of different elements, the objective is highlighting the topic in an effort to concentrate on the contemporary testing in the Instrumental music of ours by restricting itself to performing aspect and producing aspect of Hindustani Classical Instrumental Music. The study additionally features a look on modern musical instruments, emerging bands as well as artists. Keywords: Music, instrumental, experiment 1. -

T>HE JOURNAL MUSIC ACADEMY

T>HE JOURNAL OF Y < r f . MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY IrGHTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE ' AND ART OF MUSIC XXXVIII 1967 Part.' I-IV ir w > \ dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, ^n- the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there L ^ Narada ! ” ) EDITED BY v. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1967 PUBLISHED BY 1US1C ACADEMY, MADRAS a to to 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD, MADRAS-14 bscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. X \ \ !• ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES \ COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page i BaCk (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 99 20 .. 11. BaCk (Do.) 30 *# ” J6 INSIDE PAGES: i 1st page (after Cover) 99 18 io Other pages (eaCh) 99 15 .. 9 PreferenCe will be given (o advertisers of musiCal ® instruments and books and other artistic wares. V Special positions and speCial rates on appliCation. t NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Ragb Editor, Journal of the MusiC ACademy, Madras-14. Articles on subjects of musiC and dance are accepte publication on the understanding that they are Contributed to the Journal of the MusiC ACademy. f. AIT manuscripts should be legibly written or preferabl; written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and be sigoed by the writer (giving his address in full). I The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for tb expressed by individual contributors. AH books, advertisement moneys and cheques du> intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V, B Editor. CONTENTS Page T XLth Madras MusiC Conference, 1966 OffiCial Report .. -

Y8 South Asian Dance Bhangra: Lesson 3

09/07/2020 Y8 South Asian Dance Bhangra: Lesson 3 Y8 South Asian Dance Bhangra: Lesson 3 Read through the following information in regard to South Asian Dance and in particular for this week Kathak Dance. Once you have read the information please complete the quiz. All the answers to the questions are within the information below. *Required 1. Name and Class https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1mQCE2DiUnfhcw2v0hwMhMOxH4QaNrt2qFplFWBxW3O0/edit 1/7 09/07/2020 Y8 South Asian Dance Bhangra: Lesson 3 What is South Asian Dance? South Asian dance encompasses dance forms originating from the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka) and varies between classical and non-classical dance. The classical dance forms often described as Indian Classical Dance include Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Odissi, Kuchipudi, Kathakali, Manipuri, Mohiniyattam and Sattriya. Other dance forms include Kalaripayattu or Kalari and Chhau which are influenced by martial art. The non-classical dance are Bollywood dance and folk dances such as Bhangra, Garba, Kalbelia and Bihu dance. (https://akademi.co.uk/) We are going to take a closer look at 3 of these Dance forms: Bollywood, Kathak and Bhangra. In Lesson 3 we will be looking at Bhangra Dance in more depth. Bhangra refers to several types of dance originating from the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent and it is a celebratory folk dance which welcomes the coming of spring, or Vaisakhi, as it is known. Bhangra dance is based on music from a dhol, folk singing, and the chimta (tongs with bells). The accompanying songs are small couplets written in the Punjabi language called bolis.