The Taranta–Dance Ofthesacredspider

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dramatization of Italian Tarantism in Song

Lyric Possession: A Dramatization of Italian Tarantism in Song Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Smith, Dori Marie Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 04:42:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/560813 LYRIC POSSESSION : A DRAMATIZATION OF ITALIAN TARANTISM IN SONG by Dori Marie Smith __________________________ Copyright © Dori Marie Smith 2015 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2015 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Dori Marie Smith, titled Lyric Possession: A Dramatization of Italian Tarantism in Song and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2015 Kristin Dauphinais _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2015 David Ward _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24, 2015 William Andrew Stuckey _______________________________________________________________________ Date: April 24. 2015 Janet Sturman Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur Gmbh the World's Oldest Accordion

MADE IN GERMANY Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH The world’s oldest accordion manufacturer | Since 1852 Our “Weltmeister” brand is famous among accordion enthusiasts the world over. At Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH, we supply the music world with Weltmeister solo, button, piano and folklore accordions, as well as diatonic button accordions. Every day, our expert craftsmen and accordion makers create accordions designed to meet musicians’ needs. And the benchmark in all areas of our shop is, of course, quality. 160 years of instrument making at Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH in Klingenthal, Germany, are rooted in sound craftsmanship, experience and knowledge, passed down carefully from master to apprentice. Each new generation that learns the trade of accordion making at Weltmeister helps ensure the longevity of the company’s incomparable expertise. History Klingenthal, a centre of music, is a small town in the Saxon Vogtland region, directly bordering on Bohemia. As early as the middle of the 17th century, instrument makers settled down here, starting with violin makers from Bohemia. Later, woodwinds and brasswinds were also made here. In the 19th century, mouth organ ma- king came to town and soon dominated the townscape with a multitude of workshops. By the year 1840 or thereabouts, this boom had turned Klingenthal into Germany’s largest centre for the manufacture of mouth organs. Production consolidation also had its benefits. More than 30 engineers and technicians worked to stre- Accordion production started in 1852, when Adolph amline the instrument making process and improve Herold brought the accordion along from Magdeburg. quality and customer service. A number of inventions At that time the accordion was a much simpler instru- also came about at that time, including the plastic key- ment, very similar to the mouth organ, and so it was board supported on two axes and the plastic and metal easily reproduced. -

Teaching English Through Body Movement a Pa

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF ARMENIA College of Humanities and Social Sciences Dancing – Teaching English through Body Movement A paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Foreign Language By Ninel Gasparyan Adviser: Raichle Farrelly Reader: Rubina Gasparyan Yerevan, Armenia May 7, 2014 We hereby approve that this design project By Ninel Gasparyan Entitled Dancing – Teaching English through Body Movement Be accepted in partial fulfillment for the requirements of the degree Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Foreign Language Committee on the MA Design Project ………..………………………… Raichle Farrelly ………..………………………… Rubina Gasparyan ………..………………………… Dr. Irshat Madyarov MA TEFL Program Chair Yerevan, Armenia May 7, 2014 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ….....….………………………………………..………………………… v Chapter One: Introduction …………...….………………………………………… 1 Chapter Two: Literature Review ……..…………………………………………… 3 2.1. Content-Based Instruction Models ……..……………..……………………… 5 2.1.1. The use of Dance in an EFL Classroom ………...…..……………………… 11 Chapter Three: Proposed Plan and Deliverables…………………..……………… 15 3.1. Course Description ..………………………………………………………….. 15 3.1.1. Needs and Environment Analysis ……………………..…………………… 15 3.1.2. Goals and Objectives ……………………………………………….………. 16 3.1.3. Assessment Plan …………………………………………………….…….... 17 3.1.4. Learning Plan ……..…………………………………………….…..……… 19 3.1.5. Deliverables …………………………………………………………....…… 24 Chapter Four: Reflection and Recommendations ……………………..……...…… 27 4.1. Reflection -

GALATINA (Popolazione Per Classi Di Età) 0-2 ANNI 3-10 ANNI 11-17 ANNI 18-64 ANNI Oltre 65 ANNI TOTALE 1.391 4.240 4.042 37.395 14.098 61.166

DATI DEMOGRAFICI AMBITO DI GALATINA (Popolazione per classi di età) 0-2 ANNI 3-10 ANNI 11-17 ANNI 18-64 ANNI oltre 65 ANNI TOTALE 1.391 4.240 4.042 37.395 14.098 61.166 INDICATORI SU OBIETTIVI DI SERVIZIO E COPERTURA DELLA POPOLAZIONE TARGET % posti diurni per % posti diurni OB. SERV. S.04 OB. SERV. S.05 oltre 65 Anni 11-17 anni per 18-64 anni 83,3% 25,9% 2,47% 0,27% 0,00% 0,00% 1,23% % posti utente art. % posti letto art % posti utente art. posti nido % posti utente art. 52+104 % posti letto art.66 % Comuni Serviti 60+105 ogni 100 57+58 ogni 100 58+60ter+65 ogni 100 bambini 0-2 anni ogni 100 minori ogni 100 anziani abitanti 18-64enni abitanti 18-64enni ogni 100 anziani Tabella n. 1 - Unità di offerta autorizzate al funzionamento e iscritte nel registro regionale al 4 marzo 2015 Denominazione Denominazione Denominazione Natura Provincia Sede MACROTIPOLOGIA Tipologia Num Art Reg Id Registro Registro Comune Sede Op Ricettività Titolare Gestore Sede Op Titolare Op STRUTTURA Struttura Reg 4 2007 Casa di Riposo Gruppo Casa di Riposo Celestino RESIDENZIALE PER Gruppo 21423 Anziani Celestino Galluccio appartamento Privata Galatina Lecce 63 4 Galluccio Onlus ANZIANI E DISABILI Appartamento Onlus Palazzo Galluccio Gruppo RESIDENZIALE PER Gruppo 10912 Anziani Società "Stif & Stif" Società "Stif & Stif" Appartamento "La Privata Neviano Lecce 63 6 ANZIANI E DISABILI Appartamento Tamerige" Residenza sociosanitaria Casa di Riposo RESIDENZIALE PER 8088 Anziani PALAZZO GALLUCCIO PALAZZO GALLUCCIO Privata Galatina Lecce assistenziale (RSSA) 66 21 “Celestino Galluccio” ANZIANI E DISABILI (art.66 Reg. -

Elenco Dei Licei Musicali, Dei Conservatori Di Musica Degli Istituti

ALLEGATO N. 1 – Elenco dei licei musicali, dei conservatori di musica degli istituti superiori di studi musicali e delle istituzioni di formazione musicale e coreutica autorizzate a rilasciare titoli di alta formazione musicale CONSERVATORI DI MUSICA SEDE CODICE FISCALE Antonio Buzzolla ADRIA (RO) 81004200291 Antonio Vivaldi ALESSANDRIA 80005820065 Domenico Cimarosa AVELLINO 80005510641 Niccolò Piccinni BARI 80015000724 Nicola Sala BENEVENTO 92002200621 Giovan B. Martini BOLOGNA 80074850373 Claudio Monteverdi BOLZANO 80006880217 Luca Marenzio BRESCIA 80046350171 Pierluigi da Palestrina CAGLIARI 80000960924 Lorenzo Perosi CAMPOBASSO 80008630701 Agostino Steffani CASTELFRANCO VENETO (TV) 90000250267 Bruno Maderna CESENA (FC) 90012410404 Giuseppe Verdi COMO 95050750132 Stanislao Giacomantonio COSENZA 80007270780 G.F. Ghedini CUNEO 96051810040 Giovambattista Pergolesi FERMO (AP) 90026340449 Girolamo Frescobaldi FERRARA 80009060387 Luigi Cherubini FIRENZE 80025210487 Umberto Giordano FOGGIA 80030420717 Licinio Refice FROSINONE 80007510607 Nicolò Paganini GENOVA 80043230103 Giacomo Puccini LA SPEZIA 91027910115 Alfredo Casella L'AQUILA 80007670666 Ottorino Respighi LATINA 91015440596 Tito Schipa LECCE 80010030759 Lucio Campiani MANTOVA 93001510200 Egidio R. Duni MATERA 80002900779 Arcangelo Corelli MESSINA 97002610836 Giuseppe Verdi MILANO 80096530151 Nino Rota MONOPOLI (BA) 93246150721 S. Pietro a Majella NAPOLI 80017700636 Guido Cantelli NOVARA 94005010031 Cesare Pollini PADOVA 80013920287 Vincenzo Bellini PALERMO 97169270820 Arrigo Boito -

01-ALEA Program April 2, 2018-II

F o r t i e t h S e a s o n THE NEXT ALEA III EVENTS 2 0 1 7 - 2 0 18 Music for Two Guitars Monday, April 2, 2018, 8:00 p.m. Community Music Center of Boston 34 Warren Avenue, Boston, MA 02116 Free admission ALEA III Alexandra Christodimou and Yannis Petridis, guitar duo Piano Four Hands Thursday, April 19, 2018, 8:00 p.m. TSAI Performance Center - 685 Commonwealth Avenue Theodore Antoniou, Free admission Music Director Works by Antoniou, Gershwin, Khachaturian, Paraskevas, Piazzolla, Rodriguez, Ravel, Rachmaninov, Villoldo Contemporary Music Ensemble in residence at Boston University since 1979 Laura Villafranca and Ai-Ying Chiu, piano 4 hands Celebrating 1,600 years of European Music Wednesday, May 9, 2018, 8:00 p.m. Old South Church – 645 Boylston Street, Boston, MA 02116 Music for Two Guitars Free admission On the occasion on the Europe Day 2018. Curated by CMCB faculty members Works from Medieval Byzantine and Gregorian Chant, through Bach Santiago Diaz and Janet Underhill to Skalkottas, Britten, Messiaen, Ligeti, Sciarrino and beyond. ALEA III 2018 Summer Meetings Community Music Center of Boston August 23 – September 1, 2018 Allen Hall Island of Naxos, Greece 34 Warren Avenue, Boston A workshop for composers, performers and visual artists to present their work and collaborate in new projects to be featured in 2018, 2019 and 2020 events. Daily meetings and concerts. Monday, April 2, 2018 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD OF ADVISORS I would like to support ALEA III. Artistic Director Mario Davidovsky Theodore Antoniou Spyros Evangelatos During our fortieth Please find enclosed my contribution of $ ________ Leonidas Kavakos 2017-2018 season, the need payable to ALEA III Assistant to the Artistic Director Milko Kelemen for meeting our budget is Alex Κalogeras Oliver Knussen very critical. -

Ambito – Zona Di Galatina Provincia Di Lecce

AMBITO – ZONA DI GALATINA PROVINCIA DI LECCE A M B I T O T E R R I T O R I A L E D I G A L A T I N A COMPRENDENTE I COMUNI DI: GALATINA, ARADEO, CUTROFIANO, NEVIANO, SOGLIANO CAVOUR, SOLETO AVVISO PUBBLICO PER LA PRESENTAZIONE DI PROGETTI DI CONTRASTO ALLE TOSSICODIPENDENZE ED ALTRI FENOMENI DI DIPENDENZA Premesso che: · il Piano Regionale delle Politiche Sociali prevede, nell’ambito della definizione dei Piani di Zona, che i comuni singoli, associati tra loro, d’intesa con le aziende unità sanitarie locali, con la partecipazione di tutti gli altri soggetti previsti dalla L. R. 19/2006, programmino interventi e servizi che, per tipologia e natura delle attività proposte, siano coerenti con quanto previsto dal regolamento regionale del 28/02/2000, n. 1, che ha fissato i criteri e le modalità per il finanziamento regionale dei progetti di lotta alla droga, compresa l’individuazione dei soggetti destinatari dei finanziamenti, in relazione alle aree d’intervento specifiche; · la Regione Puglia al fine di adeguare le previsioni del regolamento regionale n. 1/2000 alla riforma introdotta dalla l.r. 19/2006 ha definito apposite “linee guida” per la programmazione e la gestione degli interventi in materia di lotta alla droga; · le modifiche introdotte dalla legge regionale 19/2006 incidono anche sulle modalità di presentazione dei progetti riservando ai Comuni e alle AUSL il 50% delle risorse complessivamente destinate all’area dipendenze dei Piani di Zona per la realizzazione di servizi ed interventi secondo le previsioni del regolamento regionale 1/2000, ed il restante 50% agli enti ausiliari di cui agli articoli 115 e 116 del D.P.R. -

Tabella 1 - Indicatori Territoriali Dei Comuni Della Provincia Di Lecce

Tabella 1 - Indicatori territoriali dei comuni della provincia di Lecce Livello altimetrico (m.) Coordinate geografiche Superficie Densità Sistema Grado di Comune territoriale demografica Regione agrariaLocale del Litoraneità Del Latitudine Longitudine urbanizzazione Minimo Massimo 2011 (kmq.) 2018 (ab/kmq) Lavoro centro Nord Est Acquarica del Capo 110 99 170 39° 55' 18° 15' 18,70 247,98 Intermedio Pianura di Leuca Presicce Non litoraneo Alessano 140 0 189 39° 53' 18° 20' 28,69 223,05 Intermedio Pianura di Leuca Alessano Litoraneo Alezio 75 12 75 40° 04' 18° 03' 16,79 335,27 Intermedio Pianura di Gallipoli Gallipoli Non litoraneo Alliste 54 0 86 39° 57' 18° 05' 23,53 284,44 Intermedio Pianura di Gallipoli Taviano Litoraneo Andrano 110 0 134 39° 59' 18° 23' 15,71 304,93 Intermedio Pianura di Leuca Tricase Litoraneo Aradeo 75 60 86 40° 08' 18° 08' 8,58 1.078,96 Intermedio Pianura di Nardò Galatina Non litoraneo Arnesano 33 17 44 40° 20' 18° 06' 13,56 298,86 Intermedio Pianura di Copertino Lecce Non litoraneo Bagnolo del Salento 96 82 104 40° 09' 18° 21' 6,74 269,54 Intermedio Pianura Salentina centrale Maglie Non litoraneo Botrugno 95 83 114 40° 04' 18° 19' 9,75 278,87 Intermedio Pianura di Otranto Maglie Non litoraneo Calimera 54 39 98 40° 15' 18° 17' 11,18 619,63 Intermedio Pianura di Lecce Melendugno Non litoraneo Campi Salentina 33 27 62 40° 24' 18° 01' 45,88 224,22 Intermedio Pianura di Copertino Lecce Non litoraneo Cannole 100 28 106 40° 09' 18° 21' 20,35 82,31 Basso Pianura di Lecce Maglie Non litoraneo Caprarica di Lecce 60 43 101 -

The Aesthetics of Arranged Traditional Music in Turkey Eliot Bates CUNY Graduate Center

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2010 Mixing for Parlak and Bowing for a Büyük Ses: The Aesthetics of Arranged Traditional Music in Turkey Eliot Bates CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Follow this and additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Bates, Eliot, "Mixing for Parlak and Bowing for a Büyük Ses: The Aesthetics of Arranged Traditional Music in Turkey" (2010). CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/487 This Article is brought to you by CUNY Academic Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of CUNY Academic Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL . 54, NO. 1 E TH N OMUSICOLOGY WI N T E R 2010 Mixing for Parlak and Bowing for a Büyük Ses: The Aesthetics of Arranged Traditional Music in Turkey ELIOT BAT E S / University of Maryland, College Park n this paper I explore the production aesthetics that define the sound I of most arranged traditional music albums produced in the early 2000s in Istanbul, Turkey.1 I will focus on two primary aesthetic characteristics, the achievement of which consume much of the labor put into tracking and mix- ing: parlak (“shine”) and büyük ses (“big sound”). Parlak, at its most basic, consists of a pronounced high frequency boost and a pattern of harmonic distortion characteristics, and is often described by studio musicians and engi- neers in Turkey as an exaggeration of the perceived brightness of the majority of Anatolian folk instruments.2 Büyük ses, which in basic terms connotes a high density of heterogeneous musical parts, in contrast to parlak has no rela- tion to any known longstanding Anatolian musical performing traditions or timbral aesthetics, and is a recent development in Istanbul-produced record- ings. -

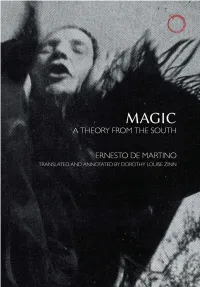

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Introducing the Harmonica Box Concertina

Introducing The Harmonica, Button Box and Anglo Concertina The harmonica, the Anglo concertina and the button accordion are three instruments that operate on a similar blow/draw or push/pull principle. This means, in theory at least, that if you can get your mind around the way one of them works then moving on to another will be familiar, even relatively painless. So if you can rattle out a tune on the mouth organ you should at least have an idea how the concertina or button accordion works. A full octave of musical tones or steps contains 12 notes, 13 if you count the next octave note. (To get an octave note just means doubling, or halving, the frequency, such as by halving the length of a guitar string, or causing a reed to vibrate half, or twice, as fast). A scale containing all those 12 notes is called a chromatic scale. Most basic songs and tunes however only need a select 8 of these tones, the familiar ‘doh, re, me, fa, so, la, ti, doh’ thing, that’s 7 only notes, or 8 if you count the second ‘doh’. This is called a diatonic scale. The harmonica, Anglo concertina and button accordion are diatonic free reed instruments, in general they come with just the basic 7 notes that you will need to play most tunes, in one set key or starting point. And they make those notes when air is blown over little metal reeds that sit snugly in a frame. Each button, or hole on a harmonica, has two reeds and makes two different sounds, one when the bellows are pushed together, or you blow into a harmonica, another when the bellows are pulled apart, or you draw air in. -

La Danca Che Cura

University of Helsinki ”LA DANZA CHE CURA” - DANCERS’ PERCEPTIONS OF SOUTHERN ITALIAN TARANTELLA Master’s thesis Sofia Silfvast Faculty of Arts Department of World Cultures Master’s Degree Programme in Intercultural Encounters Major: Religious Studies January 2015 2 Tiedekunta Laitos Humanistinen Maailman kulttuurien laitos Tekijä Sofia Silfvast Työn nimi “La danza che cura” – Dancers’ Perceptions of Southern Italian Tarantella Oppiaine Uskontotiede – Master’s Programme in Intercultural Encounters Työn laji Aika Sivumäärä Pro Gradu Tammikuu 2015 103 Tiivistelmä Tutkielmani käsittelee Etelä-Italian perinteistä tanssia tarantellaa, jonka suosio on lisääntynyt huomattavasti viimeisen 20 vuoden aikana. Tarantella on yleisnimitys musiikille ja tansseille, joille yhteistä on 6/8 rytmi ja tamburello-rumpu. Tarantella on piirissä tai pareittain tanssittavaa. Tarantella tarkoittaa ‘pientä hämähäkkiä’. Nimi antaa viitteitä sen yhteydestä tarantismiin, musiikilla ja tanssilla parantamisen rituaaliin, jota harjoitettiin 1950-luvulle asti Etelä-Italian Salenton seudulla. Tutkimusaineistoni koostuu 11 teemahaastattelusta, jotka toteutin kahdella kenttätyömatkalla vuonna 2013. Haastattelin tanssijoita, jotka toimivat esiintyjinä, opettajina ja perinteenvälittäjinä Italiassa ja eri puolilla Eurooppaa. Haastattelujen lisäksi osallistuin tanssityöpajoihin sekä musiikki- ja tanssitapahtumiin. Tiedonhankintaani helpotti italian kielen taito ja teatteriharrastustaustani. Tutkimukseni tavoitteena on tarkastella erilaisia diskursseja, joita liitetään tarantellaan