Internal Rebellions and External Threats: a Model of Government Organizational Forms in Ancient China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

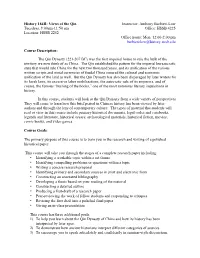

Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00Am-11:50 Am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office Hours: Mon

History 184R: Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00am-11:50 am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office hours: Mon. 12:00-2:00 pm [email protected] Course Description: The Qin Dynasty (221-207 BC) was the first imperial house to rule the bulk of the territory we now think of as China. The Qin established the pattern for the imperial bureaucratic state that would rule China for the next two thousand years, and its unification of the various written scripts and metal currencies of feudal China ensured the cultural and economic unification of the land as well. But the Qin Dynasty has also been disparaged by later writers for its harsh laws, its excessive labor mobilizations, the autocratic rule of its emperors, and of course, the famous “burning of the books,” one of the most notorious literary inquisitions in history. In this course, students will look at the Qin Dynasty from a wide variety of perspectives. They will come to learn how this brief period in Chinese history has been viewed by later authors and through the lens of contemporary culture. The types of material that students will read or view in this course include primary historical documents, legal codes and casebooks, legends and literature, historical essays, archaeological materials, historical fiction, movies, comic books, and video games. Course Goals: The primary purpose of this course is to train you in the research and writing of a polished historical paper. This course will take you through the stages of a complete research paper -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

The King's Power Dominating Society—A Re-Examination of Ancient Chinese

The King's Power Dominating Society—A Re-examination of Ancient Chinese Society Liu Zehua Abstract In terms of social formation, the most important characteristic of traditional Chinese society was how the king’s power dominated the society. Ever since the emergence of written records, we see that ancient China has had a most prominent interest group, that of the nobility and high officials, centered around the king (and later the emperor). Of all the kinds of power exerted on Chinese society, the king’s was the ultimate power. In the formation process of kingly power, a corresponding social structure was also formed. Not only did this central group include the king or emperor, the nobles, and the bureaucratic landlords, but the “feudal landlord ecosystem” which was formed within that group also shaped the whole society in a fundamental way. As a special form of economic redistribution, corruption among officials provided the soil for the growth of bureaucratic landlords. At the foundation of this entire bureaucratic web was always the king and his authority. In short, ancient Chinese society is a power-dependent structure centered on the king’s power. The major social conflict was therefore the conflict between the dictatorial king’s power and the rest of society. Keywords king’s power; landlord; social classes; despotism; social form Society of Imperial Power: Reinterpreting China’s “Feudal Society” Feng Tianyu 1 Abstract To call the period from Qin Dynasty to Qing Dynasty a “feudal society” is a misrepresentation of China’s historical reality. The fengjian system only occupied a secondary position in Chinese society from the time of Qin. -

The Transition of Inner Asian Groups in the Central Plain During the Sixteen Kingdoms Period and Northern Dynasties

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties Fangyi Cheng University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cheng, Fangyi, "Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2781. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2781 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2781 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties Abstract This dissertation aims to examine the institutional transitions of the Inner Asian groups in the Central Plain during the Sixteen Kingdoms period and Northern Dynasties. Starting with an examination on the origin and development of Sinicization theory in the West and China, the first major chapter of this dissertation argues the Sinicization theory evolves in the intellectual history of modern times. This chapter, in one hand, offers a different explanation on the origin of the Sinicization theory in both China and the West, and their relationships. In the other hand, it incorporates Sinicization theory into the construction of the historical narrative of Chinese Nationality, and argues the theorization of Sinicization attempted by several scholars in the second half of 20th Century. The second and third major chapters build two case studies regarding the transition of the central and local institutions of the Inner Asian polities in the Central Plain, which are the succession system and the local administrative system. -

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the Leader of the Zhou

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the leader of the Zhou (Chou), a subject people living in the west of the Chinese kingdom, overthrew the last king of the Shang Dynasty. King Wu died shortly after this victory, but his family, the Ji, would rule China for the next few centuries. Their dynasty is known as the Zhou Dynasty. The Mandate of Heaven After overthrowing the Shang Dynasty, the Zhou propagated a new concept known as the Mandate of Heaven. The Mandate of Heaven became the ideological basis of Zhou rule, and an important part of Chinese political philosophy for many centuries. The Mandate of Heaven explained why the Zhou kings had authority to rule China and why they were justified in deposing the Shang dynasty. The Mandate held that there could only be one legitimate ruler of China at one time, and that such a king reigned with the approval of heaven. A king could, however, loose the approval of heaven, which would result in that king being overthrown. Since the Shang kings had become immoral—because of their excessive drinking, luxuriant living, and cruelty— they had lost heaven’s approval of their rule. Thus the Zhou rebellion, according to the idea, took place with the approval of heaven, because heaven had removed supreme power from the Shang and bestowed it upon the Zhou. Western Zhou After his death, King Wu was succeeded by his son Cheng, but power remained in the hands of a regent, the Duke of Zhou. The Duke of Zhou defeated rebellions and established the Zhou Dynasty firmly in power at their capital of Fenghao on the Wei River (near modern-day Xi’an) in western China. -

Serfdom and Slavery 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SERFDOM AND SLAVERY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M L Bush | 9781317887485 | | | | | Serfdom and Slavery 1st edition PDF Book Thus, the manorial system exhibited a degree of reciprocity. In Early Modern France, French nobles nevertheless maintained a great number of seigneurial privileges over the free peasants that worked lands under their control. Villeins generally rented small homes, with a patch of land. German History. Hull Domesday Project. Encyclopedia of Human Rights: Vol. Cosimo, Inc. State serfs were emancipated in Why was the abbot so determined to keep William in prison? Book of Winchester. Clergy Knowledge worker Professor. With the growing profitability of industry , farmers wanted to move to towns to receive higher wages than those they could earn working in the fields, [ citation needed ] while landowners also invested in the more profitable industry. Admittedly, after that strong stance the explanation in the textbooks tends to get a bit hazy, and for good reason. Furthermore, the increasing use of money made tenant farming by serfs less profitable; for much less than it cost to support a serf, a lord could now hire workers who were more skilled and pay them in cash. The land reforms in northwestern Germany were driven by progressive governments and local elites [ citation needed ]. Hidden categories: Wikipedia articles incorporating a citation from the Encyclopaedia Britannica with Wikisource reference All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from December Articles with unsourced statements from June Wikipedia articles needing clarification from December All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from December Vague or ambiguous geographic scope from April Articles with unsourced statements from May Articles with unsourced statements from May In such a case he could strike a bargain with a lord of a manor. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Scribes in Early Imperial

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Scribes in Early Imperial China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Tsang Wing Ma Committee in charge: Professor Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, Chair Professor Luke S. Roberts Professor John W. I. Lee September 2017 The dissertation of Tsang Wing Ma is approved. ____________________________________________ Luke S. Roberts ____________________________________________ John W. I. Lee ____________________________________________ Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, Committee Chair July 2017 Scribes in Early Imperial China Copyright © 2017 by Tsang Wing Ma iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Professor Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, my advisor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for his patience, encouragement, and teaching over the past five years. I also thank my dissertation committees Professors Luke S. Roberts and John W. I. Lee for their comments on my dissertation and their help over the years; Professors Xiaowei Zheng and Xiaobin Ji for their encouragement. In Hong Kong, I thank my former advisor Professor Ming Chiu Lai at The Chinese University of Hong Kong for his continuing support over the past fifteen years; Professor Hung-lam Chu at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University for being a scholar model to me. I am also grateful to Dr. Kwok Fan Chu for his kindness and encouragement. In the United States, at conferences and workshops, I benefited from interacting with scholars in the field of early China. I especially thank Professors Robin D. S. Yates, Enno Giele, and Charles Sanft for their comments on my research. Although pursuing our PhD degree in different universities in the United States, my friends Kwok Leong Tang and Shiuon Chu were always able to provide useful suggestions on various matters. -

Slavery in the United States and China: a Comparative Study of the Old South and the Han Dynasty

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1988 Slavery in the United States and China: A Comparative Study of the Old South and the Han Dynasty Yufeng Wang College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, Asian History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Yufeng, "Slavery in the United States and China: A Comparative Study of the Old South and the Han Dynasty" (1988). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625472. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-kcwc-ap90 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SLAVERY IN THE UNITED STATES AND CHINA: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE OLD SOUTH AND THE HAN DYNASTY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Yufeng Wang 1988 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Approved, December 1988 Craig If. Canning Lufdwfell H. Joh: III TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT............................ iv INTRODUCTION....................... 2 CHAPTER I. HAN SOCIETY AND THE ANTEBELLUM SOUTH........... 9 CHAPTER II. SLAVE ORIGINS AND OWNERSHIP............ -

Confucianism and the Macartney Mission: Dispelling the Myth of Chinese Arrogance

CONFUCIANISM AND THE MACARTNEY MISSION: DISPELLING THE MYTH OF CHINESE ARROGANCE Sana Shakir “Every circumstance concerning us and every word that falls from our lips is minutely reported and remembered…We have indeed been very narrowly watched, and all our customs, habits and proceeding, even of the most trivial nature, observed with an inquisitiveness and jealousy which surpassed all that we had read of in the history of China. But we endeavored to always put the best face upon everything, and to preserve a perfect serenity of countenance upon all occasions.” -Lord Macartney “There is nothing we lack, as your principal envoy and others have themselves observed. We have never set much store on strange or indigenous objects, nor do we need any more of your country‟s manufactures.” -Qianlong INTRODUCTION The West has long regarded China as a self-isolated entity –an entity, nonetheless, that has been generally categorized as arrogant and unreceptive to foreign ideas and diplomatic relations. Yet while the West has been quick to accuse China of this self- conceit, it has, in turn, embraced the very rhetoric of arrogance that it so enthusiastically accuses China of. The self-restraint and frequent indifference that the Chinese have shown can not merely be simplified into expressions of conceit and superiority. To do so, as most of the West has indeed already accomplished, would do a great injustice to a civilization whose inter-workings are intricate and complex, to say the least. In order to dispel this oversimplified theory of arrogance that has been attributed to the Chinese, it is necessary to understand the context under which China regarded foreign powers and relations, as well as how it regarded its relative position in the international sphere. -

William Monroe Coleman: Writing Tibetan History

William Monroe Coleman: Writing Tibetan History (extracts) 2 William Monroe Coleman, "Writing Tibetan History: The Discourses of Feudalism and Serfdom in Chinese and Western has begun to flourish, and several works published in recent years bear testament Historiography", Master’s Thesis, East-West Centre, University of to the value of this fruitful and credible research.4 When possible, these works Hawaii (extracts) will be used to enhance Goldstein's remarkable studies and thus provide a more multi-dimensional understanding of traditional Tibet. Chapter 3: The Discourse of Serfdom in Tibet The Socio-Economic System of Traditional Tibet Introduction Traditional Tibetan lay society was, according to Goldstein, first and In his 1971 Journal of Asian Studies article, "Serfdom and Mobility: foremost differentiated into two hierarchical and hereditary strata: "aristocratic An Examination of the Institution of 'Human Lease' in Traditional Tibetan lords (sger pa) and serfs (mi ser)."5 Lords and mi ser were linked by an landed Society," Melvyn Goldstein proclaims, "Tibet was characterized by a form of estate, which was held either privately by a large aristocratic family, or by the institutionalized inequality that can be called pervasive serfdom,"1 and thereby central government in the person of a provincial district representative.6 Notably, launched his narrative of serfdom. In this chapter I will deconstruct Goldstein's when estate ownership shifted, mi ser remained with the estate, rather than with narrative of serfdom and, by privileging alternative characteristics of traditional the family that previously owned it. Bound to an estate, mi ser were also subject Tibetan society, propose a counter-narrative that more comprehensively to heavy taxation and labor obligations by their lord, and could not legally represents the dynamic nature of traditional Tibetan society. -

Property Rights in Land, Agricultural Capitalism, and the Relative Decline of Pre- Industrial China Taisu Zhang

Property Rights in Land, Agricultural Capitalism, and the Relative Decline of Pre- Industrial China Taisu Zhang This is a draft. Please do not cite without the permission of the author. Abstract Scholars have long debated how legal institutions influenced the economic development of societies and civilizations. This Article sheds new light on this debate by reexamining, from a legal perspective, a crucial segment of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century economic divergence between England and China: By 1700, English agriculture had become predominantly capitalist, reliant on ―managerial‖ farms worked chiefly by hired labor. On the other hand, Chinese agriculture counterproductively remained household-based throughout the Qing and Republican eras. The explanation for this key agricultural divergence, which created multiple advantages for English proto-industry, lies in differences between Chinese and English property rights regimes, but in an area largely overlooked by previous scholarship. Contrary to common assumptions, Qing and Republican laws and customs did recognize private property and, moreover, allowed reasonably free alienation of it. Significant inefficiencies existed, however, in the specific mechanisms of land transaction: The great majority of Chinese land transactions were ―conditional sales‖ that, under most local customs, guaranteed the ―seller‖ an interminable right of redemption at zero interest. In comparison, early modern English laws and customs prohibited the redemption of ―conditional‖ conveyances—mainly mortgages—beyond a short time frame. Consequently, Chinese farmers found it very difficult to securely acquire land, whereas English farmers found it reasonably easy. Over the long run, this impeded the spread of capitalist agriculture in China, but promoted it in England. Differences between Chinese and English norms of property transaction were, therefore, important to Qing and Republican China‘s relative economic decline. -

Society of Imperial Power: Reinterpreting China's “Feudal Society”

Journal of Chinese Humanities � (�0�5) �5-50 brill.com/joch Society of Imperial Power: Reinterpreting China’s “Feudal Society” Feng Tianyu Translated by Hou Pingping, Zhang Wenzhen Abstract To call the period from Qin Dynasty to Qing Dynasty a “feudal society” is a misrepre- sentation of China’s historical reality. The fengjian system only occupied a secondary position in Chinese society from the time of Qin. It was the system of prefectures and counties ( junxianzhi) that served as the cornerstone of the centralized power struc- ture. This system, together with the institution of selecting officials through the impe- rial examination, constituted the centralized bureaucracy that intentionally crippled the hereditary tradition and the localized aristocratic powers, and hence bolstered the unity of the empire. Feudalism in medieval Western Europe shares many similarities with that of China during the Shang and Zhou dynasties, but is quite different from the monarchical centralism since the time of Qin and Han. Categorizing the social form of the period from Qin to Qing as “feudal” makes the mistake of over-generalizing and distorting this concept. It runs counter to the original Chinese meaning of fengjian, and severely deviates from the western connotation of feudalism. Moreover, the decentralized feudalism in pre-Qin dynasties and the later centralized imperial system from Qin onwards influenced the generation and evolution of Chinese culture in vastly different ways. Keywords feudal – fengjian – imperial system * Feng Tianyu is Professor of History in the School of History, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China. E-mail: [email protected]. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���5 | doi �0.��63/�35��34�-0�0�0003Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 07:39:12PM via free access 26 feng For more than half a century on the Chinese mainland, the prevailing view on the social form of China from Qin (221-206 B.C.) to Qing (1644-1911 A.D.) is that it was a feudal society, similar to that of medieval Western Europe.