The Battle of York (1813)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Baine's [!] History of the Late](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7311/baines-history-of-the-late-307311.webp)

Baine's [!] History of the Late

y'^^^^ > .3 ^.. v-^^ .o< ^ r^: c"^ 00 ,*^ v: 0" ^ * ^t. v^^ :^, A^ iv '=t ^^ 00^ oH vO V,-^ •^.-^77;^^G^ Oo. A -f. ?: -%.%^ °-'>^i^'.' ^>- 'If, . -vV 1 "'r-t/t/'*^ "i" v^ .''^ «^r "^ - /^ ^ *<, s^ ^0 ^ ^ s}> -r;^. ^^. .- .>r-^. ^ '^ '^. ,^^«iy' c « O. ..s^J^ i^ » ,,$^ 'V. aN^' -. ^ ^ s , o * O , ^ y 0" .. °^ :f' .1 / BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN; WITH A CTJllTlCAli ATTEXmX, &c BY EBENEZER HARLOW CUMMINS, A. M. BALTIMOBE: riinted by Benja. Edes, corner of Second and Ga/.streets 1820. ADVERTISEMENT. Since the late hostilities with Great Britain, several books have been published in the United States purporting to be histories of tiie war. No one of tliem, it is believed, can be received as generally authentic: the whole adding little to the literary char- acter of the country. Of those most g-en'^rally circulated, we can speak the least favourably, as specimens of history, which means something more than compilations from newspapers, or a tirade of epithets stigmatising our adversaries. Two or three stipendi- aries occupied the fore ground in the race of the booksellers for the market of the United States, producing interesting though coarse compilations; which, while the feelings created by the war were still in Hvely existence, were read with sensations of pleas- ure. But no one now will ascribe to their works, the name, much less the character of history. Weems' life of Marion, in which the author has collated and embellished many interesting events, with the view to a popular book, has greatly superiour pretensions to either. With enough of fact to challenge, at this late day, the credence of most readers, it excels in all kinds of jest and fancy; and administers abundantly of the finest entertain- ment to the lovers of fun. -

Rather Dead Than Enslaved: the Blacks of York in the War of 1812 by Peter Meyler

The Newsletter of The Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common v. 16 No.4 Sept 2012 1 Rather Dead than Enslaved: The Blacks of 5 The Soldiers at Fort York Armoury York in the War of 1812 7 Bicentennial Timeline 2 “Particularly Torontoesque”: 8 Administrator’s Report Commemorating the Centennial of 9 Tracking Nature at Fort York the War of 1812 11 Upcoming Events 4 Brock Day in Guernsey Rather Dead than Enslaved: The Blacks of York in the War of 1812 by Peter Meyler In 1812 York may have been a “dirty straggling village,” but Upper Canada’s capital was also a place of diversity. Government officials, soldiers, merchants, and artisans mixed with clerks, servants, and even slaves in a town of barely 700 persons. The number who were Black can only be guessed at. Some were freeborn, others had escaped slavery from the United States, but a number were slaves. Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe’s 1793 Act prevented the further importation of slaves into Upper Canada, but did not free those who were enslaved. Among the province’s slave-owners was Robert Gray, the solicitor general. His household at York included his manservant, Simon Baker, Simon’s brother John, and two Black female servants. In 1804 Gray and Simon both perished when the Speedy, a ship on which they were travelling, was lost in a storm on Lake Ontario. Under Gray’s will, all his slaves were freed. During the War of 1812 John Baker left York and served with the 104th New Brunswick Regiment. He later returned to Upper Canada to live in Cornwall where he died in his nineties. -

Medical Care of American Pows During the War of 1812

Canadian Military History Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 5 2008 Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812 Gareth A. Newfield Canadian War Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Newfield, Gareth A. "Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812." Canadian Military History 17, 1 (2008) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Newfield: Medical Care of POWs Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812 Gareth A. Newfield n 2005, a service in Halifax upkeep was difficult, rendering medical Icommemorated US soldiers and care often chaotic. British medical sailors who perished in Britain’s Melville officers none the less cared for captives Island prisoner-of-war camp during adequately and comparably to the way the War of 1812 and whose remains they assisted their own forces. now lie on Deadman’s Island, a nearby peninsula. The service culminated Organization nearly a decade of debate, in which local Processing the Sick and history enthusiasts, the Canadian and Wounded American media, and Canadian and US politicians rescued the property ew formal conventions dealt with the from developers. The media in particular had Ftreatment of prisoners of war during highlighted the prisoners’ struggles with disease the period. While it was common for combatant and death, often citing the sombre memoirs of nations to agree upon temporary conventions survivors.1 Curiously, Canadian investigators once hostilities commenced, generally it was relied largely upon American accounts and did quasi-chivalric sentiments, notions of Christian little research on efforts at amelioration from the conduct, and a sense of humanitarian obligation British perspective. -

Battle of York an Account of the Eight Hours' {Battle from the Humber {Bay to the Old Fort in 'Ljefence of York on April 27, 1813 •

Centennial Series War of 1812-15 i======== The Battle of York An Account of the Eight Hours' {Battle from the Humber {Bay to the Old Fort in 'lJefence of York on April 27, 1813 • Barlow Cumberland, M.A. tttif/Stffi~\~ ) l,~;_~"-~l~J,:::;.-i~\i'f ' .)')i'_,·\_ 1i':A•l'/ BLOOR ST. BLOOR ST. BLOOR ST, r: ~ ell ('J ~ ~ :z µJ ~ ct P! c:, (lJ ;:> µ.. µ.. :r: z ;:J 0 I' . I A ~ ~I i VEEN ST. ,!N~..ST~ ~~--:--, HUMBER BAY. HARBOUR. ts.- ..ui: ..,·~.~- K' ~1..:~f!,~ .... t .:r ; .~ . ~~--~ AMERICAN FLEET 5 a111.. MOVEMENTS OF THE AMERICAN FLEET ON 27TH APRIL, 1813. CENTENNIAL SERIES, WAR OF 1812-15 The Battle of York AN ACCOUNT OF THE ~IGHT HOURS' B&TTLE FROM THE HUMBER BAY TO THE OLD FORT IN THE DEFENCE OF YORK ON 27th APRIL, 1813 BY BARLOW CUMBERLA.ND, M.A. TORONTO WILLIAM BRIGGS 1913 Copyright,Canada,1913, by BARLOW CUMBERLAND The Battle of York It used to be said, and not so many years ago, that Canada was an unhistoric country, that it had no history. Perhaps this was because our peoples in these western parts, whose beginnings of occupa tion commenced but a little over one hundred years ago, have been so much occupied with clearing the forests and developing our resources that but little time has been given to the studying and recording ·of its earlier days. Our thoughts have been de voted more to what is called the practical, rather than to the reminiscent, to the future rather than to the past. -

Canadian Archæology. an Essay

UC-NRLF Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/canadianarcholOOkingrich : Canadian Archeology, AN ESSAY. WILLIAM KIXGSFORD. MONTREAL WM. DRYSDALE & CO., 232 ST. JAMES STREET. 1886. ! ! Ach Gott ! die Kunst ist lang, Und kurz ist unser Leben. Mir wird, bei meinem kritischen Bestreben, Doch oft um Kopf und Busen bang. Wie schwer sind niclit die Mittel zu erwerben, Durch die man zu den Quellen steigt Und eh' man nur den halben Weg erreicht Musz wohl eiu armer Teufel sterben. Goethe, Faust. Ah me ! but art is long And human life is short. Oft in the throes of critic thought Have head and heart ceased to be strong. How hard the means which in our effort lie To reach the sources of what mortals know, But ere a man can half the distance go Verily, poor devil, must he die. Your home born projects prove ever the best ; they are so easy and familiar ; they put too much learning in their things now-a-days. Ben Johnson, Bartholomew Fair, Ist das Licht das Eigenthum der Flamme, wo nicht gar des Ker- zendochts? Ich enthalte mich jedes Urtheils liber solche Frage, und freue mich nur dariiber, dass Ihr dem armen Dochte, der sich brennend verzehrt, eine kleine Vergiitung verwilligen wolt fiir sein groszes gemeinnittziges Beleuchtungsverdienst Heine. Is the light the property of the flame, if it in no wa,Y be of the taper wick ? I abstain from any judgment over such a question, and I only rejoice that you are willing to make some slight amends to the poor wick, which consumes itself in burning, for its noble, universal, merit- orious service of enlightenment ! Canadian Archeology. -

Key Events & Causes: War of 1812

Key Events & Causes: War of 1812 Burning of Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress Memory Collection) Event Date Location Significance Napolean excludes British goods from "fortress American ships caught in middle as British respond with 1806 Europe Europe" blockade. British seize 1000 U.S. ships, French ca. 500. British captains took over 10,000 American citizens to man British impress American sailors 1803-1812 High seas ships. 3 miles off Chesapeake fired on by Leopard after refusing to be boarded. 3 Chesapeake -Leopard fight June 1807 Norfolk, Americans killed, 18 wounded. Virginia December Washington, Jefferson's attempt at "peaceful coercion" resulted in economic Embargo Act 1807 D.C. disaster for merchants. Calhoun, Clay, others bothered by insults to U.S. and Indian War Hawks elected to Congress 1810 U.S. presence Ohio River Tecumseh's brother (the Prophet) led attack on Harrison's army Battle of Tippecanoe 1811 Valley of 1000. June 18, Washington, Pushed by War Hawks, Madison asked for declaration. All Congress declares "Mr. Madison's War" 1812 D.C. Federalists oppose it. August British capture Ft. Mackinac Michigan U.S. lost fort as British invade American territory. 16, 1812 U.S.-- Invasion attempts of Canada 1812 Canadian 3 attempts of U.S. to invade Canada all fail. border Atlantic Victory by U.S. ship ("Old Ironsides"). Other privateers Constitution vs. Guerriere 1812 Ocean captured or burned British ships. January Kentucky troops repelled by British and Indians in bloody Battle of Frenchtown Michigan 1813 fighting. American survivors killed in Raisin River Massacre. April Toronto, U.S. troops took control of Great Lakes, burn York. -

THE WAR of 1812 - Historical Timeline

THE WAR OF 1812 - Historical Timeline key dates and events, and local significance Prepared by Heather Colautti of Windsor’s Community Museum • events with local significance are highlighted • Year Date Event Description 1811 November 7 Battle of Considered the first battle of the War of 1812. Tippecanoe, Indiana Takes place between Tecumseh’s brother, The Prophet, and William Henry Harrison (Governor of the Indian Territory’s) army 1812 June 18 US declares war on President James Madison signs war bill into law. Great Britain First time the USA declared war on another nation. 1812 June 28 News of war Colonel St. George, commander at Fort reaches Fort Amherstburg, receives word of war. With about Amherstburg 300 British regular in Amherstburg, he dispatches a detachment of militia to Sandwich. 1812 July 2 Cuyahoga Captured The Cuyahoga, traveling from Toledo to Detroit transporting some officers’ wives and invalids, along with band instruments and American Brigadier-General William Hull’s personal luggage, is captured “... in front of Fort Amherstburg, yielding 45 prisoners and among the booty, American military dispatches and even muster rolls.” 1812 July 5 Americans shell Americans under Hull arrived at Springwell Sandwich (below Detroit) – shell British guns at Sandwich. Local militias withdraw to Amherstburg. 1812 July 8 US bombarded Sandwich 1812 July 12 Americans cross the Americans land near Labadie’s mill on the south Detroit River side of the Detroit River below Hog Island (modern day Belle Isle) and “... march down the road along the bank of the river, to a point opposite the Town...” of Detroit. Hull makes the unfinished home of Francois Baby his headquarters and issues a proclamation that states the Americans fight is with Great Britain, rather than Canada, and that if they do not take up arms against Americans they “.. -

Ottawa Citizen" Almanac

) k. uo a P5t>v2- 9004 03467345 6 MADE FROM PERMAUFE® paper DNTO COPYRITE HOWARD PAPER MILLS INC. "THE OTTAWA CITIZEN" ALMANAC, FOR THE YEAR 18 6 7 EPOCHS. The year 5628 of the Jewish Era begins Sept. 30. The 31st of Queen Victoria's Reigu 20 ( begins June Mahometan Era begins May 5 The 92nd of The year 1284 of the | the Iudep. of the U. S. begins July 4 CHRONOLOGICAL CYCLES. Golden Number •••• 6 Dominical Letter «,.. F Enact - 25 Roman Indiction.. .* , JO Solar Cycle 28 Julian Period 6580 FIXED AND MOVEABLE FESTIVALS, Ac. Circumcision January 1 Low Sunday April 28 Epiphany " 6 Rogation '*' May 26 Septuagesima Sunday Febr'y. 17 Ascension Day *« 30 Quinquagesima is March 2 Whit-Sunday June 9 Ash Wednesday rt 6 Trinity " " 16 First Sunday in Lent ei 10 Corpus Christi c< 20 Annunciation " 25 St. Peter and St. Paul " 29 Palm Sunday April 14 All Saints Day Nov 1 Good Friday « 19 Advent Sunday Dec 1 Easter Sunday '* 21 Christmas Day " 25 STATUTORY HOLIDAYS. New Year's day; Epiphany; Annunciation; Good Friday; Ascension Day; Corpus Christi; St. Peter and St. Paul ; All Saints; Christmas Day ; Sundays; and all days set apart for fast or thanksgiving by Proclamation. ECLIPSES. In the year 1867 there will be four Eclipses—two of the Sun, and two of the Moon, I. —An annular Eclipse of the Sun, March 6th., invisible in Canada, II.—A partial Eclipse ofthe Moon, March 20th., visible in Central America. III.—A total Eclipse ofthe Sun, August 28th and 29th., invisible in Canada. -

Provincial Plaques Across Ontario

An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Last updated: May 25, 2021 An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Title Plaque text Location County/District/ Latitude Longitude Municipality "Canada First" Movement, Canada First was the name and slogan of a patriotic movement that At the entrance to the Greater Toronto Area, City of 43.6493473 -79.3802768 The originated in Ottawa in 1868. By 1874, the group was based in Toronto and National Club, 303 Bay Toronto (District), City of had founded the National Club as its headquarters. Street, Toronto Toronto "Cariboo" Cameron 1820- Born in this township, John Angus "Cariboo" Cameron married Margaret On the grounds of his former Eastern Ontario, United 45.05601541 -74.56770762 1888 Sophia Groves in 1860. Accompanied by his wife and daughter, he went to home, Fairfield, which now Counties of Stormont, British Columbia in 1862 to prospect in the Cariboo gold fields. That year at houses Legionaries of Christ, Dundas and Glengarry, Williams Creek he struck a rich gold deposit. While there his wife died of County Road 2 and County Township of South Glengarry typhoid fever and, in order to fulfil her dying wish to be buried at home, he Road 27, west of transported her body in an alcohol-filled coffin some 8,600 miles by sea via Summerstown the Isthmus of Panama to Cornwall. She is buried in the nearby Salem Church cemetery. Cameron built this house, "Fairfield", in 1865, and in 1886 returned to the B.C. gold fields. He is buried near Barkerville, B.C. "Colored Corps" 1812-1815, Anxious to preserve their freedom and prove their loyalty to Britain, people of On Queenston Heights, near Niagara Falls and Region, 43.160132 -79.053059 The African descent living in Niagara offered to raise their own militia unit in 1812. -

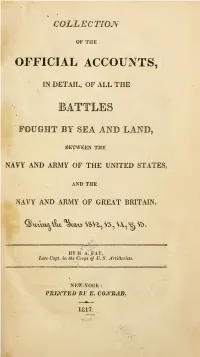

Collection of the Official Accounts, in Detail, of All the Battles Fought By

COLLECTION OF THE OFFICIAL ACCOUNTS, IN DETAIL, OF ALL THE FOUGHT BY SEA AND LAND, BETWEEN THE NAVY AND ARMY OF THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NAVY AND ARMY OF GREAT BRITAIN, BYH A. FAY, Late Capt. in the Corps of U. S. Artillerists. NEW-YORK : PRLYTEJJ Bl £. CO^^BAD, 1817. 148 nt Southern District of Niw-York, ss. BE IT REMEMBERED, that on the twenty-ninth day (if Jpril, m the forty-first year of the Independence of the United States of America, H. A. Fay, of the said District, hath deposited in this office the title ofa book, the right whereof he claims as author and proprietor, in the words andjigures following, to wit: " Collection of the official accounts, in detail, of all the " battles fought, by sea and land, between the navy and array of the United " States, and the nary and army of Great Britain, during the years 1812, 13, " 14, and 15. By H. A. Fay, late Capt. in the corps of U. S. Artillerists."-- In conformity to the Act of Congress of the United States, entitled •' An Act for the encouragement of Learning, by securing the copies of Maps, Charts, and Books to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the time therein mentioned." And also to an act, entitled " an Act, supplementary to an Act, entitled an Act for the encouragement of Learning, by securing the copies of Maps, Charts, and Books to the authors and proprietors of suck copies, during the times therein mentioned, and extending the benefits thereof to the arts ofdesigning, engraving, and etching historical and other prints." THERON RUDD, Clerk of the Southern District of New-York. -

The Historical Significance of General Sir Isaac Brock: Part 2

War of 1812, Historical Thinking Lesson 12 The Historical Significance of General Sir Isaac Brock: Part 2 by Elizabeth Freeman-Shaw Suggested grade level: Intermediate/Senior Suggested time: 2 class periods Brief Description of the Task In this lesson students will explore why General Sir Isaac Brock is considered to be historically significant, and wrestle with whether or not he should be. Historical Thinking Concepts • Historical Significance • Use of Evidence (primary and secondary) Learning Goals Students will be able to: • participate in an activity that allows them to understand the concept of historical significance • identify the role and historical significance of General Sir Isaac Brock in the War of 1812 • review secondary accounts of Isaac Brock to determine the case for significance • synthesize data into qualities of greatness • use excerpts from primary sources to determine the validity of historians’ conclusions. Materials Each student will need copies of all Primary Sources and Worksheets (in the Appendices file). Prior Knowledge It would be an asset for students to be familiar with: The Historical Thinking Project, 2012 War of 1812, Historical Thinking Lesson 12 1. Earlier events leading up to the declaration of war, key personalities, the political structure of British North America, and the causes of the war. 2. The concept of historical significance (See The Historical Thinking Project website, http://www.historicalthinking.ca/concept/historical- significance) Assessment Students may be evaluated based on the work completed with: • Worksheet 1 – Decoding Secondary Sources • Worksheet 2 – Note-taking, Secondary Sources • Worksheet 3 – Examining Primary Sources Detailed Lesson Plan Focus Question: Why is it that even though General Brock was killed in the early hours of the Battle of Queenston Heights and Colonel Roger Sheaffe lead the British forces to victory, Brock is more remembered than Sheaffe? Part A – Exploring a Controversy 1. -

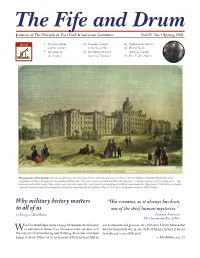

Fife and Drum Spring 2021

Journal of The Friends of Fort York & Garrison Common Vol.25, No.1 Spring 2021 8 A young officer 20 Canada’s women 24 Update from the fort and his mother in the Great War 25 Wayne Reeves 9 The lands of 22 Revolution of Love retires as Curator the Asylum leaves out Toronto 26 Mrs. Traill’s Advice The grounds of the Asylum were an elegant place for a leisurely stroll in 1870. The predecessor of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, it was regarded in its day as progressive, innovative and humane. Yet even its name is a stark reminder that the past – a foreign country, as L.P. Hartley wrote – can be an uncomfortable space. These lawns may once have been the council and camping grounds of Mississauga warriors. Story, page 9. Illustration is a hand- coloured version of an ink drawing published in the Canadian Illustrated News, May 21, 1870, artist unknown; courtesy CAMH Archives Why military history matters “War remains, as it always has been, to all of us one of the chief human mysteries.” by Margaret MacMillan Svetlana Alexievich, The Unwomanly Face of War ar. The word alone raises a range of emotions from horror war excitement and glamour. As a historian I firmly believe that to admiration. Some of us choose to avert our eyes as if we have to include war in our study of human history if we are Wthe very act of remembering and thinking about war somehow to make any sense of the past. brings it closer. Others of us are fascinated by it and can find in see MacMillan, page 13 In the summer of 1813, USS Oneida sails out of Sackets Harbor, its base at the eastern end of Lake Ontario.