Poles in the Regiment De Watteville and Regiment De Meuron During the War of 1812

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Niagara Flag Is Crown Jewel of Area's Rich History

Winter 2009 Fort Niagara TIMELINE The War of 1812 Ft. Niagara Flag The War of 1812 Photo courtesy of Angel Art, Ltd. Lewiston Flag is Crown Ft. Niagara Flag History Jewel of Area’s June 1809: Ft. Niagara receives a new flag Mysteries that conforms with the 1795 Congressional act that provides for 15 starts and 15 stripes Rich History -- one for each state. It is not known There is a huge U.S. flag on display where or when it was constructed. (There were actually 17 states in 1809.) at the new Fort Niagara Visitor’s Center that is one of the most valued historical artifacts in the December 19, 1813: British troops cap- nation. The War of 1812 Ft. Niagara flag is one of only 20 ture the flag during a battle of the War of known surviving examples of the “Stars and Stripes” that were 1812 and take it to Quebec. produced prior to 1815. It is the earliest extant flag to have flown in Western New York, and the second oldest to have May 18, 1814: The flag is sent to London to be “laid at the feet of His Royal High- flown in New York State. ness the Prince Regent.” Later, the flag Delivered to Fort Niagara in 1809, the flag is older than the was given as a souvenir to Sir Gordon Star Spangled Banner which flew over Ft. McHenry in Balti- Drummond, commander of the British more. forces in Ontario. Drummond put it in his As seen in its display case, it dwarfs home, Megginch Castle in Scotland. -

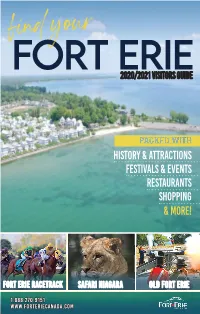

2020/2021 Visitors Guide

2020/2021 Visitors Guide packed with History & Attractions Festivals & Events Restaurants Shopping & more! fort erie Racetrack safari niagara old fort erie 1.888.270.9151 www.forteriecanada.com And Mayor’s Message They’re Off! Welcome to Fort Erie! We know that you will enjoy your stay with us, whether for a few hours or a few days. The members of Council and I are delighted that you have chosen to visit us - we believe that you will find the xperience more than rewarding. No matter your interest or passion, there is something for you in Fort Erie. 2020 Schedule We have a rich history, displayed in our historic sites and museums, that starts with our lndigenous peoples over 9,000 years ago and continues through European colonization and conflict and the migration of United Empire l yalists, escaping slaves and newcomers from around the world looking for a new life. Each of our communities is a reflection of that histo y. For those interested in rest, relaxation or leisure activities, Fort Erie has it all: incomparable beaches, recreational trails, sports facilities, a range of culinary delights, a wildlife safari, libraries, lndigenous events, fishin , boating, bird-watching, outdoor concerts, cycling, festivals throughout the year, historic battle re-enactments, farmers’ markets, nature walks, parks, and a variety of visual and performing arts events. We are particularly proud of our new parks at Bay Beach and Crystal Ridge. And there is a variety of places for you to stay while you are here. Fort Erie is the gateway to Canada from the United States. -

THE WAR of 1812: European Traces in a British-American Conflict

THE WAR OF 1812: European Traces in a British-American Conflict What do Napoleon, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the War of 1812 in North America have in common? 99 men – and this is their story… Peg Perry Lithuanian Museum-Archives of Canada December 28, 2020 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Setting the Stage ................................................................................................................................. 2 The de Watteville Regiment ................................................................................................................ 4 North America – the War of 1812 ....................................................................................................... 9 De Watteville’s Arrival in North America April to May 1813 ............................................................. 13 Loss of the Flank Companies – October 5, 1813 ............................................................................... 14 The Battle of Oswego - May 5-7, 1814 .............................................................................................. 16 The Battle of Fort Erie – August 15-16, 1814 .................................................................................... 19 Fort Erie Sortie – September 17, 1814 .............................................................................................. 23 After the War – the Land Offer in Canada........................................................................................ -

10-2 157410 Volumes 1-7 Open FA 10-2

10-2_157410_volumes_1-7_open FA 10-2 RG Volume Reel no. Title / Titre Dates no. / No. / No. de de bobine volume RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-05-27 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-08-31 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-11-17 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Copy made of a surrender from the Six Nations to Caleb Benton, John Livingston and 1796-12-28 Associates, entered into 9 July 1788 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 William Dummer Powell to Peter Russell respecting Joseph Brant 1797-01-05 RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Robert Prescott to Peter Russell respecting the Indian Department - Enclosed: Copy of Duke of 1797-04-26 Portland to Prescott, 13 December 1796, stating that the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada will head the Indian Department, but that the Department will continue to be paid from the military chest - Enclosed: Copy of additional instructions to Lieutenant Governor U.C., 15 December 1796, respecting the Indian Department - Enclosed: Extract, Duke of Portland to Prescott, 13 December 1796, respecting Indian Department in U.C. RG10-A-1-a 1 10996 Robert Prescott to Peter Russell sending a copy of Robert Liston's letter - Enclosed: Copy, 1797-05-18 Robert Liston to Prescott, 22 April 1797, respecting the frontier posts RG10-A-1-a -

Some Incidents and Circumstances Written by William F. Haile in the Course of His Life, 1859 Creator: Haile, William F

Title: Some Incidents and Circumstances Written by William F. Haile in the Course of his Life, 1859 Creator: Haile, William F. Dates of 1859 Record Group RG 557 Material: Number: Summary of Contents: - The first part of the document traces Mr. Haile’s lineage. His father, James Haile was a farmer. His grandfather, Amos Haile was a sailor for the early part of his life. He was placed on a British man-of- war in about 1758. He escaped and settled in Putney. (p.1) - His father’s mother’s maiden name was Parker. His mother’s maiden name was Campbell. Her father was a captain in the Revolutionary Army. (p.2) - His earliest memories revolve around the death of his aunt and the funeral of General Washington (although he did not witness this). At the time, his father was a Lieutenant in a regiment militia of Light Dragoons who wore red coats. (p.3) - In 1804, an addition was added to the Haile house which necessitated that William was to stay home to help with the building. He continued to study and read on his own. He was particularly interested in Napoleon Bonaparte’s victories. In that same year he was sent to Fairfield Academy where Reverend Caleb Alexander was the principal. (p.4) - On June 1, 1812, William was appointed as an Ensign in the Infantry of the Army of the United States. He was put into the recruiting service at Nassau (20 miles east of Albany) where he remained until September. (p.4) - He was assigned to the 11th Regiment of the W.S. -

Constitution and Government 33

CONSTITUTION AND GOVERNMENT 33 GOVERNORS GENERAL OF CANADA. FRENCH. FKENCH. 1534. Jacques Cartier, Captain General. 1663. Chevalier de Saffray de Mesy. 1540. Jean Francois de la Roque, Sieur de 1665. Marquis de Tracy. (6) Roberval. 1665. Chevalier de Courcelles. 1598. Marquis de la Roche. 1672. Comte de Frontenac. 1600. Capitaine de Chauvin (Acting). 1682. Sieur de la Barre. 1603. Commandeur de Chastes. 1685. Marquis de Denonville. 1607. Pierredu Guast de Monts, Lt.-General. 1689. Comte de Frontenac. 1608. Comte de Soissons, 1st Viceroy. 1699. Chevalier de Callieres. 1612. Samuel de Champlain, Lt.-General. 1703. Marquis de Vaudreuil. 1633. ii ii 1st Gov. Gen'l. (a) 1714-16. Comte de Ramesay (Acting). 1635. Marc Antoine de Bras de fer de 1716. Marquis de Vaudreuil. Chateaufort (Administrator). 1725. Baron (1st) de Longueuil (Acting).. 1636. Chevalier de Montmagny. 1726. Marquis de Beauharnois. 1648. Chevalier d'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1747. Comte de la Galissoniere. (c) 1651. Jean de Lauzon. 1749. Marquis de la Jonquiere. 1656. Charles de Lauzon-Charny (Admr.) 1752. Baron (2nd) de Longueuil. 1657. D'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1752. Marquis Duquesne-de-Menneville. 1658. Vicomte de Voyer d'Argenson. j 1755. Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal. 1661. Baron Dubois d'Avaugour. ! ENGLISH. ENGLISH. 1760. General Jeffrey Amherst, (d) 1 1820. James Monk (Admin'r). 1764. General James Murray. | 1820. Sir Peregrine Maitland (Admin'r). 1766. P. E. Irving (Admin'r Acting). 1820. Earl of Dalhousie. 1766. Guy Carleton (Lt.-Gov. Acting). 1824. Lt.-Gov. Sir F. N. Burton (Admin'r). 1768. Guy Carleton. (e) 1828. Sir James Kempt (Admin'r). 1770. Lt.-Gov. -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

The War of 1812 Magazine Issue 21 January 2014

The War of 1812 Magazine Issue 21 January 2014 Donald E. Graves. And All Their Glory Past: Fort Erie: Plattsburgh and the Final Battles in the North. Montreal: Robin Brass Studio, 2013. 419 pages, maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index. $24.95 (Canada)/$27.95 (U.S.) paper. Review by Robert Burnham And All Their Glory Past is the third book in Donald Graves “Forgotten Soldiers Trilogy”. Unlike his previous two volumes, Where Right and Glory Lead and Field of Glory: The Battle of Crysler’s Farm, 1813, which dealt with either a specific geographic area or a single battle, And All Their Glory Past, for the most part, covers the action along the border between the United States and Canada in the latter half of 1814. This was a critical time of the war, for the fledgling American Army had become a force to be reckoned with, while the war on the European continent had ended and the British were able to send a large number of battle hardened regulars from Wellington’s disbanded Peninsular Army. Although the book is divided into five parts, it really focuses on two major campaigns and a cavalry raid unlike any previously seen in North America. Much of the book centers around Fort Erie, which sits on the Canadian side of the Niagara River about a kilometer from Lake Erie. Whoever held the fort, controlled any traffic that moved on the river into the Great Lakes. Because of it strategic importance, it would become the site of the bloodiest battle on Canadian soil. Fort Erie was captured by the Americans in early July 1814 and much of And All Their Glory Past is about the attempt by the British to re-take it from August to November 1814. -

B 46 - Commission of Inquiry Into the Red River Disturbances

B 46 - Commission of inquiry into the Red River Disturbances. Lower Canada RG4-B46 Finding aid no MSS0568 vols. 620 to 621 R14518 Instrument de recherche no MSS0568 Pages Access Mikan no Media Title Label no code Scope and content Extent Names Language Place of creation Vol. Ecopy Dates No Mikan Support Titre Étiquette No de Code Portée et contenu Étendue Noms Langue Lieu de création pages d'accès B 46 - Commission of inquiry into the Red River Disturbances. Lower Canada File consists of correspondence and documents related to the resistance to the settlement of Red River; the territories of Cree and Saulteaux and Sioux communities; the impact of the Red River settlement on the fur trade; carrying places (portage routes) between Bathurst, Henry Bathurst, Earl, 1762-1834 ; Montréal, Lake Huron, Lake Superior, Lake Drummond, Gordon, Sir, 1772-1854 of the Woods, and Red River. File also (Correspondent) ; Harvey, John, Sir, 1778- consists of statements by the servants of 1 folder of 1 -- 1852(Correspondent) ; Loring, Robert Roberts, ca. 5103234 Textual Correspondence 620 RG4 A 1 Open the Hudson's Bay Company and statements textual e011310123 English Manitoba 1815 137 by the agents of the North West Company records. 1789-1848(Correspondent) ; McGillivray, William, related to the founding of the colony at 1764?-1825(Correspondent) ; McNab, John, 1755- Red River. Correspondents in file include ca. 1820(Correspondent) ; Selkirk, Thomas Lord Bathurst; Lord Selkirk; Joseph Douglas, Earl of, 1771-1820(Correspondent) Berens; J. Harvey; William McGillivray; Alexander McDonell; Miles McDonell; Duncan Cameron; Sir Gordon Drummond; John McNab; Major Loring; John McLeod; William Robinsnon, and the firm of Maitland, Garden & Auldjo. -

Medical Care of American Pows During the War of 1812

Canadian Military History Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 5 2008 Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812 Gareth A. Newfield Canadian War Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Newfield, Gareth A. "Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812." Canadian Military History 17, 1 (2008) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Newfield: Medical Care of POWs Medical Care of American POWs during the War of 1812 Gareth A. Newfield n 2005, a service in Halifax upkeep was difficult, rendering medical Icommemorated US soldiers and care often chaotic. British medical sailors who perished in Britain’s Melville officers none the less cared for captives Island prisoner-of-war camp during adequately and comparably to the way the War of 1812 and whose remains they assisted their own forces. now lie on Deadman’s Island, a nearby peninsula. The service culminated Organization nearly a decade of debate, in which local Processing the Sick and history enthusiasts, the Canadian and Wounded American media, and Canadian and US politicians rescued the property ew formal conventions dealt with the from developers. The media in particular had Ftreatment of prisoners of war during highlighted the prisoners’ struggles with disease the period. While it was common for combatant and death, often citing the sombre memoirs of nations to agree upon temporary conventions survivors.1 Curiously, Canadian investigators once hostilities commenced, generally it was relied largely upon American accounts and did quasi-chivalric sentiments, notions of Christian little research on efforts at amelioration from the conduct, and a sense of humanitarian obligation British perspective. -

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org $4.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Background 03 Trails and Settlements 03 Shelters and Dwellings 04 Clothing and Dress 07 Arts and Crafts 08 Religions 09 Medicine 10 Agriculture, Hunting, and Fishing 11 The Fur Trade 12 Five Major Tribes of Ohio 13 Adapting Each Other’s Ways 16 Removal of the American Indian 18 Ohio Historical Society Indian Sites 20 Ohio Historical Marker Sites 20 Timeline 32 Glossary 36 The Ohio Historical Society 1982 Velma Avenue Columbus, OH 43211 2 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio HISTORICAL BACKGROUND In Ohio, the last of the prehistoric Indians, the Erie and the Fort Ancient people, were destroyed or driven away by the Iroquois about 1655. Some ethnologists believe the Shawnee descended from the Fort Ancient people. The Shawnees were wanderers, who lived in many places in the south. They became associated closely with the Delaware in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Able fighters, the Shawnees stubbornly resisted white pressures until the Treaty of Greene Ville in 1795. At the time of the arrival of the European explorers on the shores of the North American continent, the American Indians were living in a network of highly developed cultures. Each group lived in similar housing, wore similar clothing, ate similar food, and enjoyed similar tribal life. In the geographical northeastern part of North America, the principal American Indian tribes were: Abittibi, Abenaki, Algonquin, Beothuk, Cayuga, Chippewa, Delaware, Eastern Cree, Erie, Forest Potawatomi, Huron, Iroquois, Illinois, Kickapoo, Mohicans, Maliseet, Massachusetts, Menominee, Miami, Micmac, Mississauga, Mohawk, Montagnais, Munsee, Muskekowug, Nanticoke, Narragansett, Naskapi, Neutral, Nipissing, Ojibwa, Oneida, Onondaga, Ottawa, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Peoria, Pequot, Piankashaw, Prairie Potawatomi, Sauk-Fox, Seneca, Susquehanna, Swamp-Cree, Tuscarora, Winnebago, and Wyandot. -

Canadian Archæology. an Essay

UC-NRLF Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/canadianarcholOOkingrich : Canadian Archeology, AN ESSAY. WILLIAM KIXGSFORD. MONTREAL WM. DRYSDALE & CO., 232 ST. JAMES STREET. 1886. ! ! Ach Gott ! die Kunst ist lang, Und kurz ist unser Leben. Mir wird, bei meinem kritischen Bestreben, Doch oft um Kopf und Busen bang. Wie schwer sind niclit die Mittel zu erwerben, Durch die man zu den Quellen steigt Und eh' man nur den halben Weg erreicht Musz wohl eiu armer Teufel sterben. Goethe, Faust. Ah me ! but art is long And human life is short. Oft in the throes of critic thought Have head and heart ceased to be strong. How hard the means which in our effort lie To reach the sources of what mortals know, But ere a man can half the distance go Verily, poor devil, must he die. Your home born projects prove ever the best ; they are so easy and familiar ; they put too much learning in their things now-a-days. Ben Johnson, Bartholomew Fair, Ist das Licht das Eigenthum der Flamme, wo nicht gar des Ker- zendochts? Ich enthalte mich jedes Urtheils liber solche Frage, und freue mich nur dariiber, dass Ihr dem armen Dochte, der sich brennend verzehrt, eine kleine Vergiitung verwilligen wolt fiir sein groszes gemeinnittziges Beleuchtungsverdienst Heine. Is the light the property of the flame, if it in no wa,Y be of the taper wick ? I abstain from any judgment over such a question, and I only rejoice that you are willing to make some slight amends to the poor wick, which consumes itself in burning, for its noble, universal, merit- orious service of enlightenment ! Canadian Archeology.