Proceedings Viiith International Docomomo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HERITAGE UNDER SIEGE in BRAZIL the Bolsonaro Government Announced the Auction Sale of the Palácio Capanema in Rio, a Modern

HERITAGE UNDER SIEGE IN BRAZIL the Bolsonaro Government announced the auction sale of the Palácio Capanema in Rio, a modern architecture icon that was formerly the Ministry of Education building FIRST NAME AND FAMILY NAME / COUNTRY TITLE, ORGANIZATION / CITY HUBERT-JAN HENKET, NL Honorary President of DOCOMOMO international ANA TOSTÕES, PORTUGAL Chair, DOCOMOMO International RENATO DA GAMA-ROSA COSTA, BRASIL Chair, DOCOMOMO Brasil LOUISE NOELLE GRAS, MEXICO Chair, DOCOMOMO Mexico HORACIO TORRENT, CHILE Chair, DOCOMOMO Chile THEODORE PRUDON, USA Chair, DOCOMOMO US LIZ WAYTKUS, USA Executive Director, DOCOMOMO US, New York IVONNE MARIA MARCIAL VEGA, PUERTO RICO Chair, DOCOMOMO Puerto Rico JÖRG HASPEL, GERMANY Chair, DOCOMOMO Germany PETR VORLIK / CZECH REPUBLIC Chair, DOCOMOMO Czech Republic PHILIP BOYLE / UK Chair, DOCOMOMO UK OLA ODUKU/ GHANA Chair, DOCOMOMO Ghana SUSANA LANDROVE, SPAIN Director, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico, Barcelona IVONNE MARIA MARCIAL VEGA, PUERTO RICO Chair, DOCOMOMO Puerto Rico CAROLINA QUIROGA, ARGENTINA Chair, DOCOMOMO Argentina RUI LEAO / MACAU Chair, DOCOMOMO Macau UTA POTTGIESSER / GERMANY Vice-Chair, DOCOMOMO Germany / Berlin - Chair elect, DOCOMOMO International / Delft ANTOINE PICON, FRANCE Chairman, Fondation Le Corbusier PHYLLIS LAMBERT. CANADA Founding Director Imerita. Canadian Centre for Architecture. Montreal MARIA ELISA COSTA, BRASIL Presidente, CASA DE LUCIO COSTA/ Ex Presidente, IPHAN/ Rio de Janeiro JULIETA SOBRAL Diretora Executiva, CASA DE LUCIO COSTA, Rio de Janeiro ANA LUCIA NIEMEYER/ BRAZIL -

The Making of the Sainsbury Centre the Making of the Sainsbury Centre

The Making of the Sainsbury Centre The Making of the Sainsbury Centre Edited by Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas 2 This publication accompanies the exhibition: Unless otherwise stated, all dates of built projects SUPERSTRUCTURES: The New Architecture refer to their date of completion. 1960–1990 Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Building credits run in the order of architect followed 24 March–2 September 2018 by structural engineer. First published in Great Britain by Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Norwich Research Park University of East Anglia Norwich, NR4 7TJ scva.ac.uk © Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, 2018 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0946 009732 Exhibition Curators: Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas Book Design: Johnson Design Book Project Editor: Rachel Giles Project Curator: Monserrat Pis Marcos Printed and bound in the UK by Pureprint Group First edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Superstructure The Making of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Contents Foreword David Sainsbury 9 Superstructures: The New Architecture 1960–1990 12 Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas Introduction 13 The making of the Sainsbury Centre 16 The idea of High Tech 20 Three early projects 21 The engineering tradition 24 Technology transfer and the ‘Kit of Parts’ 32 Utopias and megastructures 39 The corporate ideal 46 Conclusion 50 Side-slipping the Seventies Jonathan Glancey 57 Under Construction: Building the Sainsbury Centre 72 Bibliography 110 Acknowledgements 111 Photographic credits 112 6 Fo reword David Sainsbury Opposite. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

Mokelumne Hill Design Review Guidelines

MOKELUMNE HILL DESIGN REVIEW GUIDELINES 13 August 2012 By Mokelumne Hill Design Review Committee For Calaveras County Board of Supervisors 1 Introduction The Mokelumne Hill Community Plan (Community Plan) recognizes the historic architecture and character of the community and seeks to preserve these assets. A Historic Design Review District (Historic District) and Gateway Design Review Areas (Gateway Areas) have been identified and all development (new and remodeling) requiring a permit or approval by Calaveras County within the Historic District and Gateway Areas is subject to these Design Review Guidelines (Guidelines) (see Appendix A maps). In addition, all Designated Historic Buildings as identified in Appendix B are subject to these Guidelines. Areas outside of the Historic District and Gateway Areas are also recognized as having valuable architectural and historical qualities and the application of these Guidelines will be encouraged but not required in those areas. The Guidelines, in principal, were approved as part of the Mokelumne Hill Community Plan in 1988. These completed Guidelines were approved by Resolution No. 2012- 163 on November 13, 2012 by the Calaveras County Board of Supervisors. Acknowledgements This document was initially drafted in 2005 by members of the Mokelumne Hill History Society, Julia Costello and Paula Leitzell, with the architectural descriptions and identifications contributed by Judith Marvin, Registered Architectural Historian. The authors drew heavily from the Design Review Guidelines of Truckee, Sutter Creek, and Jackson, and from other examples throughout the American West. Final revisions in 2012 responded to comments by County Staff and were accomplished by the Mokelumne Hill Design Review Committee comprised of Julia Costello, Mike Dell’Orto, Marcy Hosford, Marilyn Krause, and Terry Weatherby. -

Il Linguaggio Della Luce Secondo Vittorio Storaro MAGIC LANTERN Vittorio Storaro’S Language of Light – Paolo Calafiore

NEW BIM LIBRARY AVAILABLE 329 Luce e genius loci Park Associati Light and genius loci: Park Associati La luce nelle città Un'inchiesta Light in the cities: A reportage Vittorio Storaro Una vita per la luce Vittorio Storaro A Life in Light Outdoor LED Lighting Solutions for architecture and urban spaces. Poste ta ane spa – Sped. 1, LO/M n°46) art. 1,comma (conv. 353/2003 – D.L. n L. 27.02.2004 – n A.P. 1828-0560 SSN caribonigroup.com 2019 Anno / year 57 – n.329 2019 trimestrale / quarterly – € 15 Reverberi: innovazione nella SMART CITY TECNOLOGIE ALL’AVANGUARDIA PER CITTÀ INTELLIGENTI LTM: SENSORE LUMINANZA/TRAFFICO e condizioni metereologiche Reverberi Enetec investe nella “Computer vision” e lancia il sensore LTM. Misura della luminanza della strada monitorata, del fl usso di traffi co e delle condizioni meteo debilitanti, in particolare strada bagnata, nebbia, neve. Informazioni che, trasmesse ai sistemi della gamma Reverberi ed Opera, permettono la regolazione in tempo reale ad anello chiuso del fl usso luminoso. I test fi eld hanno dimo- strato potenzialità di risparmio energetico dell’ordine del 30%, ed aggiuntive al 25%-35% conseguibili con dispositivi di regolazione basati su cicli orari. t$POGPSNFBMMB6/*F$&/QBSUFTVJTFOTPSJEJMVNJOBO[B t$SJUFSJ"NCJFOUBMJ.JOJNJ $". EJBDRVJTUPEFMMB1VCCMJDB"NNJOJ TUSB[JPOFEFM <5065,,<967,( Reverberi Enetec srl - [email protected] - Tel 0522-610.611 Fax 0522-810.813 Via Artigianale Croce, 13 - 42035 Castelnovo né Monti - Reggio Emilia www.reverberi.it Everything comes from the project Demí With OptiLight -

Xi'an Declaration on the Conservation of Modern Heritage in Different

XI’AN DECLARATION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MODERN HERITAGE IN DIFFERENT CONTEXTS Adopted in Xi’an, China st by the 1 Council Assembly of Docomomo China and Delegates of the 2013 Xi’an International Conference on Modern Architectural Heritage “Other MoMo, Other Heritage” on 10 October 2013 1 Preamble Meeting in the ancient city of Xi’an on 8 October 2013, at the invitation of Xian University of Architecture and Technology on the occasion of the 1st Council Assembly of Docomomo China and the celebrations marking the foundation of Docomomo China Council and Docomomo China’s commitment in inheriting China’s longstanding endeavor to ensure the safeguard and conservation of modern cultural heritage as part of its sustainable and human development; Benefiting from the broad range of discussions and reflections shared by professionals, historians, preservation officers, researchers and teachers from Docomomo International, ICOMOS and UIA during the 2013 Xi’an International Conference on Modern Architectural Heritage “Other MoMo, Other Heritage” and learning from a broad range of experience from China and world-wide authorities, institutions, and specialists in providing sufficient care and management for modern heritage buildings, sites and neighborhoods in appropriate methods and conservation/rehabilitation philosophy specific to each different cultural context; Taking note of the international and professional interests in documentation and conservation of modern heritage in different context as expressed in the Eindhoven Statement (1990) and -

Narrative and Representation in French Colonial Literature of Indochina

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Narrative and Representation in French Colonial Literature of Indochina. Jean Marie turcotte Walls Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Walls, Jean Marie turcotte, "Narrative and Representation in French Colonial Literature of Indochina." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5703. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5703 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the qualify of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Structuralism (Architecture) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 6

Structuralism (architecture) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 6 Structuralism (architecture) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Structuralism as a movement in architecture and urban planning evolved around the middle of the 20th century. It was a reaction to CIAM-Functionalism (Rationalism), which had led to a lifeless expression of urban planning that ignored the identity of the inhabitants and urban forms. Two different manifestations of Structuralist architecture exist. Sometimes these occur in combination with each other. On the one hand, there is the Aesthetics of Number, formulated by Aldo van Eyck in 1959. This concept can be compared to cellular tissue. The "Aesthetics of Number" can also be described as "Spatial Configurations in Architecture". European Space Centre ESTEC in Noordwijk, restaurant conference-hall On the other hand, there is the Architecture of Lively library, 1989 (Aldo van Eyck and Hannie Variety (Structure and Coincidence), formulated by van Eyck) John Habraken in 1961. This second concept is related to user participation in housing. The "Architecture of Lively Variety" can also be called "Architecture of Diversity" or "Pluralistic Architecture". Structuralism in a general sense is a mode of thought of the 20th century, which came about in different places, at different times and in different fields. It can also be found in linguistics, anthropology, philosophy and art. Contents ■ 1 Origins ■ 2 Manifesto ■ 3 Otterlo Congress, Participants ■ 4 Theoretical Origins ■ 5 Housing Estates, Buildings and Projects ■ 6 Bibliography ■ 7 Further Configurations in Architecture and Urbanism ■ 8 Amsterdam, Barcelona, Manhattan and Venice Origins Structuralism in architecture and urban planning had its origins in the Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) after World War II. -

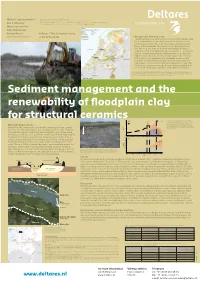

Embanked Floodplains Along the Rivers Rhine and Meuse, Areas That Are Flooded During High-Discharge Conditions (Fig

Michiel J. van der Meulen1,2* 1 Deltares, PO box 85467, 3508 AL Utrecht, Netherlands 2 TNO – Geological Survey of the Netherlands, PO box 80015, NL-3508 TA Utrecht, Netherlands Ane P. Wiersma1,2 3 Utrecht University, Faculty of Geosciences, Department of Physical Geography, PO box 80115, NL-3508 TC Utrecht, Netherlands 4 Alterra, Wageningen University and Research Centre, PO box 47, NL-6700 AA Wageningen, Netherlands Marcel van der Perk3 Hans Middelkoop3 Noortje Hobo3,4 Deltares / TNO Geological Survey *[email protected] of the Netherlands Background, Aim and scope The Netherlands has vast resources of clay that are exploited for the fabrication of structural-ceramic products such as bricks and roof tiles (Fig. 1, 2). Most clay is extracted from the so-called embanked floodplains along the rivers Rhine and Meuse, areas that are flooded during high-discharge conditions (Fig. 3, 4). Riverside clay extraction is – at least in theory – compensated by deposition. Based on a sediment balance (deposition vs. extraction), we explore the extent to which clay can be regarded as a renewable resource, with potential for sustainable use. Beyond that, we discuss the implications for river and sediment management, especially for the large engineering works that are to be undertaken to increase the discharge capacities of the Rhine and Meuse. Fig. 1: Occurrences of clay in the Netherlands that are extractable, i.e., having (1) a thickness ≥ 1 m without intercalations, and (2) < 25% chance of encountering particulate organic material or shells. For details of the underlying resource assessment see Van der Meulen et al. (2005, 2007). -

Downloads/2003 Essay.Pdf, Accessed November 2012

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91b0909n Author Alomaim, Anas Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Anas Alomaim 2016 © Copyright by Anas Alomaim 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 by Anas Alomaim Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Sylvia Lavin, Chair Kuwait started the process of its nation building just few years prior to signing the independence agreement from the British mandate in 1961. Establishing Kuwait’s as modern, democratic, and independent nation, paradoxically, depended on a network of international organizations, foreign consultants, and world-renowned architects to build a series of architectural projects with a hybrid of local and foreign forms and functions to produce a convincing image of Kuwait national autonomy. Kuwait nationalism relied on architecture’s ability, as an art medium, to produce a seamless image of Kuwait as a modern country and led to citing it as one of the most democratic states in the Middle East. The construction of all major projects of Kuwait’s nation building followed a similar path; for example, all mashare’e kubra [major projects] of the state that started early 1960s included particular geometries, monumental forms, and symbolic elements inspired by the vernacular life of Kuwait to establish its legitimacy. -

The Anchor, Volume 86.02: September 14, 1973

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 1973 The Anchor: 1970-1979 9-14-1973 The Anchor, Volume 86.02: September 14, 1973 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1973 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 86.02: September 14, 1973" (1973). The Anchor: 1973. Paper 13. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1973/13 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 86, Issue 2, September 14, 1973. Copyright © 1973 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 1970-1979 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 1973 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. City Council sets plans for *• renovating Eighth Street by Dave DeKok "The mayor appointed a study committee of five including my- Like many other small cities, self and Larry Harris, who worked Holland has a downtown area for the City of Kalamazoo when which, while not really ugly or they built their mall," he said. rundown, could best be described THE PLAN which evolved as drab. To cope with this prob- from the committee's work re- lem, the city has laid out a beauti- tains traffic on 8th Street, al- fication program which ultimately though part of it will be one way. will transform 8th Street into a The street will be lined with trees, drive-through park of sorts, com- which will be planted in dirt plete with trees and benches. -

Design,Architecture, and Decorative Arts the Library of David A. Hanks

Design,Architecture, and Decorative Arts The Library of David A. Hanks (1298 titles in circa 1320 volumes) Partial catalogue – projected to be 1500 volumes ARS LIBRI THE LIBRARY OF DAVID A. HANKS General works p. 1 -- 61 Monographs on Architects p. 62 -- 81 GENERAL WORKS 1 ABBOTT, LYMAN, ET AL. The House and Home: A Practical Book. By Lyman Abbott, L.W. Betts, Elizabeth Bisland, H.C. Candee, John M. Gerard, Constance Cary Harrison, P.G. Hubert, Jr., Thomas Wentworth Higginson, M.G. Humphreys, M.C. Jones, E.W. McGlasson, Samuel Parsons, Jr., J. West Roosevelt, W.O. Stoddard, Kate Douglas Wiggin. 2 vols. xii, (4), 400pp., 5 color plates; xii, 397, (1)pp., 6 color plates. 400 illus. 4to. Orig. publisher’s cloth (slightly rubbed). New York (Charles Scribner’s Sons), 1894-1896. 2 (ABSOLUT COMPANY) LEWIS, RICHARD W. Absolut Book: The Absolut Vodka Advertising Story. xiii, (1), 274pp. Prof. illus. in color. Lrg. 4to. Wraps. Boston/Tokyo (Journey Editions), 1996. 3 ACKERMANN, RUDOLPH. Ackermann’s Regency Furniture & Interiors. Text by Pauline Agius. Introduction by Stephen Jones. 200pp. 188 illus. (partly color). Lrg. sq. 4to. Cloth. d.j. Published to mark the centenary of H. Blairman & Sons. Marlborough, Wiltshire (The Crowood Press), 1984. 4 ADAMSON, JEREMY. American Wicker: Woven Furniture from 1850 to 1930. Woven furniture from 1850 to 1930. 175, (1)pp. Prof. illus. (partly color). 4to. Wraps. Published on the occasion of the exhibition at The Renwick Gallery of the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. New York (Rizzoli), 1993. 5 ADLIN, JANE.