ART DECO and BRAZILIAN MODERNISM a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb. 7 to Apr. 30, 2017 Great Hall

Ministry of Culture and Museu de Arte To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Moderna de São Paulo present exhibition that inaugurated Brazilian modernism, Anita Malfatti: 100 Years of Modern Art gathers at FEB. 7 MAM’s Great Hall about seventy different works covering the path of one of the main names in TO Brazilian art in the 20th century. Anita Malfatti’s exhibition in 1917 was crucial to the emergence of the group who would champion modern art in Brazil, so much so that APR. 30, critic Paulo Mendes de Almeida considered her as the “most historically critical character in the 2017 1922 movement.” Regina Teixeira de Barros’ curatorial work reveals an artist who is sensitive to trends and discussions in the first half of the 20th century, mindful of her status and her choices. This exhibition at MAM recovers drawings and paintings by Malfatti, divided into three moments in her path: her initial years that consecrated her as “trigger of Brazilian modernism”; the time she spent training in Paris and her naturalist production; and, finally, her paintings with folk themes. With essays by Regina Teixeira de Barros and GREAT Ana Paula Simioni, this edition of Moderno MAM Extra is an invitation for the public to get to know HALL this great artist’s choices. Have a good read! MASTER SPONSORSHIP SPONSORSHIP CURATED BY REALIZATION REGINA TEIXEIRA DE BARROS One hundred years have gone by since the 3 03 ANITA Exposição de pintura moderna Anita Malfatti [Anita Malfatti Modern Painting Exhibition] would forever CON- MALFATTI, change the path of art history in Brazil. -

ARCHITECTURALLY SOUND Engineered / Zoning / Construct

Monolithic 同一方向安装 ARCHITECTURALLY SOUND Engineered / Zoning / Construct China India Rest of Asia Beijing / Tianjin / Wuhan /Shenzhen Bangalore Manila T +86 10 6465 1206 T +91 98459 14059 T +63 915 816 7127 Shanghai / Suzhou / Nanjing Chennai Seoul Hangzhou / Hefei T +91 98408 98963 T +82 2 3783 0747 T +86 21 6145 1758 Delhi Singapore Chengdu / Chongqing T +91 98104 77922 T +65 6593 1301 www.millikencarpet.com T +86 181 1727 5593 Mumbai Tokyo Guangzhou T +91 98926 00362 T +81 3 5203 8406 2710024918 T +86 20 3846 8085 Jakarta Issued Jul 2019 Hong Kong T +6221 5289 7330 T +852 3956 2259 INSPIRED. INSPIRING. 源于灵感 智启灵感 Construct, Zoning and Engineered in Art Nouveau, monolithic installation Construct and Zoning in Art Nouveau, monolithic installation 2 3 Zoning and Engineered in Baroque, monolithic installation Engineered in Baroque, monolithic installation 4 5 在不同色彩层次中丰富大面积空间。 自由拼接,拓展更多设计可能性。 Use accent color to make use of space and to expand design possibility. Construct, Zoning and Engineered in Gothic, monolithic installation 6 7 Construct, Zoning and Engineered in Art Nouveau, monolithic installation Engineered in Bauhaus, monolithic installation 8 9 Construct and Zoning in High Tech, monolithic installation 10 11 INSPIRED. INSPIRING. 源于灵感 智启灵感 Beginning with solid architectural elements, trace out a meticulous inspiring space. From dark to light, natural color transition as music notes, slowly flow along elegant and pure, brand new tones lighting up the space. 以坚实的建筑元素为起点, 勾画更细致的灵动空间。 从深到浅,颜色自然过渡, 如音符点染其中慢慢流动, 或优雅、或清新, 全新的色彩和空间区隔, 让室内的每寸光线,都瞬间被点亮。 Construct, Zoning and Engineered in Bauhaus, monolithic installation 12 13 These three patterns share the same colorline for easier coordination. -

Brief History of Architecture in N.C. Courthouses

MONUMENTS TO DEMOCRACY Architecture Styles in North Carolina Courthouses By Ava Barlow The judicial system, as one of three branches of government, is one of the main foundations of democracy. North Carolina’s earliest courthouses, none of which survived, were simple, small, frame or log structures. Ancillary buildings, such as a jail, clerk’s offi ce, and sheriff’s offi ce were built around them. As our nation developed, however, leaders gave careful consideration to the structures that would house important institutions – how they were to be designed and built, what symbols were to be used, and what building materials were to be used. Over time, fashion and design trends have changed, but ideals have remained. To refl ect those ideals, certain styles, symbols, and motifs have appeared and reappeared in the architecture of our government buildings, especially courthouses. This article attempts to explain the history behind the making of these landmarks in communities around the state. Georgian Federal Greek Revival Victorian Neo-Classical Pre – Independence 1780s – 1820 1820s – 1860s 1870s – 1905 Revival 1880s – 1930 Colonial Revival Art Deco Modernist Eco-Sustainable 1930 - 1950 1920 – 1950 1950s – 2000 2000 – present he development of architectural styles in North Carolina leaders and merchants would seek to have their towns chosen as a courthouses and our nation’s public buildings in general county seat to increase the prosperity, commerce, and recognition, and Trefl ects the development of our culture and history. The trends would sometimes donate money or land to build the courthouse. in architecture refl ect trends in art and the statements those trends make about us as a people. -

Canções E Modinhas: a Lecture Recital of Brazilian Art Song Repertoire Marcía Porter, Soprano and Lynn Kompass, Piano

Canções e modinhas: A lecture recital of Brazilian art song repertoire Marcía Porter, soprano and Lynn Kompass, piano As the wealth of possibilities continues to expand for students to study the vocal music and cultures of other countries, it has become increasingly important for voice teachers and coaches to augment their knowledge of repertoire from these various other non-traditional classical music cultures. I first became interested in Brazilian art song repertoire while pursuing my doctorate at the University of Michigan. One of my degree recitals included Ernani Braga’s Cinco canções nordestinas do folclore brasileiro (Five songs of northeastern Brazilian folklore), a group of songs based on Afro-Brazilian folk melodies and themes. Since 2002, I have been studying and researching classical Brazilian song literature and have programmed the music of Brazilian composers on nearly every recital since my days at the University of Michigan; several recitals have been entirely of Brazilian music. My love for the music and culture resulted in my first trip to Brazil in 2003. I have traveled there since then, most recently as a Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Professor at the Universidade de São Paulo. There is an abundance of Brazilian art song repertoire generally unknown in the United States. The music reflects the influence of several cultures, among them African, European, and Amerindian. A recorded history of Brazil’s rich music tradition can be traced back to the sixteenth-century colonial period. However, prior to colonization, the Amerindians who populated Brazil had their own tradition, which included music used in rituals and in other aspects of life. -

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

Histories of Nineteenth-Century Brazilian

Perspective Actualité en histoire de l’art 2 | 2013 Le Brésil Histories of nineteenth-century Brazilian art: a critical review of bibliography, 2000-2012 Histoires de l’art brésilien du XIXe siècle : un bilan critique de la bibliographie, 2000-2012 Histórias da arte brasileira do século XIX: uma revisão critica da bibliografia Geschichten der brasilianischen Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts : eine kritische Bilanz der Bibliographie, 2000-2012 Storie dell’arte brasiliana dell’Ottocento: un bilancio critico della bibliografia, 2000-2012 Historias del arte brasileño del siglo XIX: un balance crítico de la bibliografía, 2000-2012 Rafael Cardoso Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/3891 DOI: 10.4000/perspective.3891 ISSN: 2269-7721 Publisher Institut national d'histoire de l'art Printed version Date of publication: 31 December 2013 Number of pages: 308-324 ISSN: 1777-7852 Electronic reference Rafael Cardoso, « Histories of nineteenth-century Brazilian art: a critical review of bibliography, 2000-2012 », Perspective [Online], 2 | 2013, Online since 30 June 2015, connection on 01 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/3891 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ perspective.3891 Histories of nineteenth-century Brazilian art: a critical review of bibliography, 2000-2012 Rafael Cardoso The history of nineteenth-century Brazilian art has undergone major changes over the first years of the twenty-first century. It would be no exaggeration to say that more has been done in the past twelve years than in the entire preceding century, at least in terms of a scholarly approach to the subject. A statement so sweeping needs to be qualified, of course, and it is the aim of the present text to do just that. -

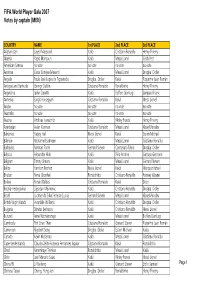

Final MEN by Coach and Captain

FIFA World Player Gala 2007 Votes by captain (MEN) COUNTRY NAME 1st PLACE 2nd PLACE 3rd PLACE Afghanistan Sayed Maqsood Kaká Cristiano Ronaldo Henry Thierry Algeria Yazid Mansouri Kaká Messi Lionel Cech Petr American Samoa no vote no vote no vote no vote Andorra Óscar Sonejee Masand Kaká Messi Lionel Drogba Didier Angola Paulo José Lopes de Figueiredo Drogba Didier Kaká Riquelme Juan Román Antigua and Barbuda George Dublin Cristiano Ronaldo Ronaldinho Henry Thierry Argentina Javier Zanetti Kaká Buffon Gianluigi Lampard Frank Armenia Sargis Hovsepyan Cristiano Ronaldo Kaká Messi Lionel Aruba no vote no vote no vote no vote Australia no vote no vote no vote no vote Austria Andreas Ivanschitz Kaká Ribéry Franck Henry Thierry Azerbaijan Aslan Karimov Cristiano Ronaldo Messi Lionel Klose Miroslav Bahamas Happy Hall Messi Lionel Kaká Essien Michael Bahrain Mohamed Salmeen Kaká Messi Lionel Cristiano Ronaldo Barbados Norman Forde Gerrard Steven Cannavaro Fabio Drogba Didier Belarus Alexander Hleb Kaká Pirlo Andrea Gattuso Gennaro Belgium Timmy Simons Kaká Messi Lionel Gerrard Steven Belize Harrison Rochez Messi Lionel Kaká Márquez Rafael Bhutan Pema Chophel Ronaldinho Cristiano Ronaldo Rooney Wayne Bolivia Ronald Baldes Cristiano Ronaldo Kaká Deco Bosnia-Herzegovina Zvjezdan Misimovic Kaká Cristiano Ronaldo Drogba Didier Brazil Lucimar da Silva Ferreira (Lucio) Gerrard Steven Messi Lionel Klose Miroslav British Virgin Islands Avondale Williams Kaká Cristiano Ronaldo Drogba Didier Bulgaria Dimitar Berbatov Kaká Cristiano Ronaldo Messi Lionel Burundi -

Adam Joseph Shellhorse Dissertation-UC Berkeley

The Limits of the Letter: The Politics of Representation and Margins in Latin American Vanguard Writings of the 1950s and 60s by Adam Joseph Shellhorse A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ana Maria Mão-de-Ferro Martinho, Chair Professor Richard Rosa Professor Ivonne del Valle Professor Laura E. Pérez Fall 2010 The Limits of the Letter: The Politics of Representation and Margins in Latin American Vanguard Writings of the 1950s and 60s Copyright 2010 by Adam Joseph Shellhorse Abstract The Limits of the Letter: The Politics of Representation and Margins in Latin American Vanguard Writings of the 1950s and 60s by Adam Joseph Shellhorse Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Ana Maria Mão-de-Ferro Martinho, Chair Throughout this study, I theorize and explore the consequences of the self-reflexive text in the literary writings of João Cabral de Melo Neto, Osman Lins, and David Viñas. I argue that what unites these writers is not solely the context of neocolonialism and underdevelopment in the 1950s and 60s in Brazil and Argentina but the properly vanguard problem and gesture of mediating the present and politics, as I trace in their theoretical writings, letters and literary texts their shared concern with making literature relevant, functional and dynamic in a public sphere -

Baroque Poetics and the Logic of Hispanic Exceptionalism by Allen E

Baroque Poetics and the Logic of Hispanic Exceptionalism by Allen E. Young A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Francine Masiello, Co-chair Professor Michael Iarocci, Co-chair Professor Robert Kaufman Fall 2012 Abstract Baroque Poetics and the Logic of Hispanic Exceptionalism by Allen Young Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professors Francine Masiello and Michael Iarocci, Chairs In this dissertation I study the how the baroque is used to understand aesthetic modernity in twentieth-century Spain and Latin America. My argument is that the baroque, in contemporary Hispanic and Latin American studies, functions as a myth of cultural exceptionalism, letting critics recast avant-garde and postmodern innovation as fidelity to a timeless essence or identity. By viewing much contemporary Spanish-language as a return to a baroque tradition—and not in light of international trends—critics in effect justify Spain and Latin America’s exclusion from broader discussions of modern literature. Against this widespread view, I propose an alternative vision drawn from the work of Gerardo Diego, José Lezama Lima and Severo Sarduy. These authors see the baroque not as an ahistorical, fundamentally Hispanic sensibility located outside the modern, but as an active dialogue with the wider world. In very different ways, they use the baroque to place the Hispanic world decidedly inside global aesthetic modernity. In contrast to most contemporary scholarship on the topic, I do not take the baroque to be a predefined aesthetic practice, readily identifiable in seventeenth- or twentieth- century authors. -

Translating Brazil: from Transnational Periodicals to Hemispheric Fictions, 1808-2010

Translating Brazil: From Transnational Periodicals to Hemispheric Fictions, 1808-2010 By Krista Marie Brune A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Natalia Brizuela, Co-chair Professor Candace Slater, Co-chair Professor Scott Saul Spring 2016 Abstract Translating Brazil: From Transnational Periodicals to Hemispheric Fictions, 1808-2010 by Krista Marie Brune Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Natalia Brizuela, Co-chair Professor Candace Slater, Co-chair This dissertation analyzes how travel and translation informed the construction of Brazil as modern in the 19th century, and how similar processes of transnational translation continue to shape the cultural visibility of the nation abroad in the contemporary moment. By reading journals, literary works, and cultural criticism, this study inserts Brazilian literature and culture into recent debates about translatability, world literature, and cosmopolitanism, while also underscoring the often-overlooked presence of Brazilians in the United States. The first half of the dissertation contends that Portuguese-language periodicals Correio Braziliense (London, 1808-1822), Revista Nitheroy (Paris, 1836), and O Novo Mundo (New York, 1870-1879) translated European and North American ideas of technology and education to a readership primarily in Brazil. The transnational circulation of these periodicals contributed to the self- fashioning of intellectuals who came to define the nation. To suggest parallels between Brazil and the United States in the late 19th century, the analysis of O Novo Mundo focuses on discourses of nation, modernity, and technological progress emerging in the hemispheric travels of scientists, intellectuals, and the Brazilian empire Dom Pedro II, and in the national displays at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. -

A Novel Application of Fuzzy Set Theory and Topic Model in Sentence Extraction for Vietnamese Text

IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.10 No.8, August 2010 41 A Novel Application of Fuzzy Set Theory and Topic Model in Sentence Extraction for Vietnamese Text Ha Nguyen Thi Thu 1† and Nguyen Thien Luan2††, †Department of Computer Science, Electric Power University ,235 Hoang Quoc Viet, Ha noi, Viet Nam ††Faculty of Information Technology, Le Qui Don Technical University,100 Hoang Quoc Viet, Ha Noi, Viet Nam Summary on the method of calculating the frequency of words in Vietnamese language has common characteristics with some sentences is not appropriate . On the other hand, study on Asian languages such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean ... They do Vietnamese text summary is now something new, corpus not define words based on spaces. In this article, we present a for Vietnamese text summarization or word segmentation method that application of Fuzzy set theory and topic model to is still limited. extract sentences in Vietnamese texts which have been categorized by topic. This method based on identification of important features as : length of sentence, weight of terms in We studied Vietnamese text that categorized by topic and sentences, position of sentences ..., then extracting important found that with each different theme, weight of words sentences according to the ratio, this ratio indicate which (hereafter called terms) would depend on the different sentences in original text will be extracted. We also built a topics. Therefore, we have built sets of terms for each system based on this method and experiments have obtained topic and applied Fuzzy theory in determining degree of good results, satisfying the given requirements. -

Pagu: a Arte No Feminino Como Performance De Si

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Interdisciplinar em Performances Culturais, para obtenção do título de Mestra em Performances Culturais pela Universidade Federal de Goiás. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Sainy Coelho Borges Veloso. Co-orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Marcela Toledo França de Almeida. GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. i ii iii Dedico este trabalho a quem sabe que a pele é fina diante da abertura do peito, que o coração a toca. Por quem sabe que é impossível viver por certos caminhos sem lutar e não brigar pela vida. Para quem entende que a paz e perdão não tem nada de silencioso quando já se viveu algumas guerras. E por quem vive como se sentisse o seu desaparecimento a cada dia, pois as flores não perdem a sua cor, apenas vivem o suficiente para não desbotar. iv AGRADECIMENTOS Não agradecerei neste trabalho a nomes específicos que me atravessaram na minha caminhada enquanto o escrevia, mas sim as experiências que passei a viver nesse período de tempo em que pela primeira vez me permite viver sem ser apenas agredida. Pelos dias que passei a cuidar de mim mesma. Pela minha caminhada em análise que me permitiu entender subjetivamente o que eu buscava quando coloquei essa temática como pesquisa a ser realizada.