The Horse in European History, 1550-1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untitled Leaves Clues About the Man Whose Portrait He Captured

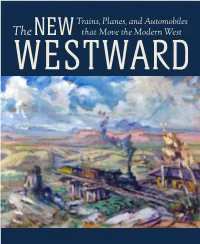

October 15, 2016–February 12, 2017 Published on the occasion of the exhibition The New Westward: Trains, Planes, and Automobiles that Move the Modern West organized by the Tucson Museum of Art and Historic Block October 15, 2016–February 12, 2017 ©Tucson Museum of Art and Historic Block CURATOR AND AUTHOR: Christine C. Brindza, James and Louise Glasser Curator of Art of the American West, Tucson Museum of Art FOREWORD: Jeremy Mikolajczak, Chief Executive Officer EDITOR: Katie Perry DESIGN: Melina Lew PRINTER: Arizona Lithographers, Tucson, Arizona ISBN: 978-0-911611-21-2 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2016947252 Tucson Museum of Art and Historic Block 140 North Main Avenue Tucson, Arizona 85701 tucsonmuseumofart.org FRONT COVER: Ray Strang (1893–1957), Train Station, c.1950, oil on paper, 14 x 20 in. Collection of the Tucson Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Dorothy Gibson. 1981.50.20 CONTENTS 07 Foreword Jeremy Mikolajczak, Chief Executive Officer 09 Author Acknowledgements 11 The New Westward: Trains, Planes, and Automobiles that Move the Modern West Christine C. Brindza 13 Manifest Destiny, Westward Expansion, and Prequels to Western Imagery in the Modern Era 19 Trains: A Technological Sublime 27 Airplanes: Redefining Western Expanses 33 The Automobile: The Great Innovation 39 Works Represented 118 Bibliography 120 Exhibition and Catalogue Sponsors FOREWORD The Tucson Museum of Art is proud to present The New Westward: Trains, Planes, and Automobiles that Move the Modern West, a thematic exhibition examining the role transportation technology has played in the American West in visual art. In today’s fast-moving, digitally-connected world, it is easy to overlook the formative years of travel and the massive overhauls that were achieved for railroads, highways, and aircraft to reach the far extended terrain of the West. -

Berlin.Pdf Novels by Arthur R.G

http://www.acamedia.info/literature/princess/A_Princess_In_Berlin.pdf Novels by Arthur R.G. Solmssen Rittenhouse Square (1968) Alexander's Feast (1971) The Comfort Letter (1975) A Princess in Berlin (1980) Takeover Time (1986) The Wife of Shore (2000) Copyright 2002: Arthur R.G. Solmssen ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Jacket painting: 'Dame mit Federboa' Gustav Klimt, Oil on canvas, 69 x 55,8 cm, 1909, Wien: Österreichische Galerie Belvedere. Source: The Androom Archives (http://www.xs4all.nl/~androom/welcome.htm). ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Internet Edition published 2002 by Acamedia at www.acamedia.info/literature/princess/A_Princess_In_Berlin.htm www.acamedia.info/literature/princess/A_Princess_In_Berlin.pdf ------------------------------------------------------------------------ A Princess in Berlin: English Summary Publisher: Little, Brown & Company, Boston/Toronto, 1980 Berlin 1922: Pandemonium reigns in the capital of Germany after the Allied victory in World War I and the fall of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The proletariat have swarmed out, waving the red banners of Communism; private armies of unemployed, disaffected veterans - Freikorps- roam the streets thrashing the Communists. The Weimar Republic ts estaablished under the protection of the Freikorps. An explosion of radical music, theater, and art manifests the seething rancor and nervous energy of the people. The most insane, paralyzing inflation the world has known makes life a misery for the hungry, desperate populace . Although the flower of their kind lie buried in Flanders fields, a few aristocratic families preserve their privileged, even exquisite lives: boating parties at summer palaces, chamber music in great townhouses on Sunday afternoons. This is the rich backdrop of "A Princess in Berlin", a social novel in the grand tradition of e.g. Theodor Fontane in the Germany of the 19th century. -

Lot 1 from Krivevac Stables 1 the Property of Mr

LOT 1 FROM KRIVEVAC STABLES 1 THE PROPERTY OF MR. JOHN McLOUGHLIN Danzig Northern Dancer Blue Ocean (USA) Pas de Nom Foreign Courier Sir Ivor BAY FILLY Courtly Dee (IRE) Nomination Dominion February 25th, 2002 Stoneham Girl Rivers Maid (Second Produce) (GB) Persian Tapestry Tap On Wood (1992) Persian Polly E.B.F. nominated. 1st dam STONEHAM GIRL (GB): placed twice at 2 years; also placed once over hurdles; She also has a yearling filly by Wizard King (GB). 2nd dam PERSIAN TAPESTRY: 2 wins and £7,702 at 3 and 5 years inc. Midsomer Norton Handicap, Bath, placed 3 times; dam of 3 winners: Triple Blue (IRE) (c. by Bluebird (USA)): 2 wins and £26,039 at 2 years, 2000, placed 7 times inc. 2nd ABN Amro Futures Ltd Dragon S., Sandown Park, L. 3rd Vodafone Woodcote S., Epsom, L. and City Index Sirenia S., Kempton Park, L. Amra (IRE): 5 wins in Turkey and £127,308 at 2 to 4 years, 2001 and placed 9 times. Need You Badly (GB): winner at 3 years, placed 5 times, broodmare. Spanish Thread (GB): placed once at 2 years, broodmare. Stoneham Girl (GB): see above. Flower Hill Lad (IRE): placed 5 times at 2, 3 and 5 years. She also has a yearling filly by Bluebird (USA) and a colt foal by Bluebird (USA). 3rd dam Persian Polly: winner at 2 years, placed twice inc. 3rd Park S., Leopardstown, Gr.3; dam of 7 winners inc. LAKE CONISTON (IRE), Champion older sprinter in Europe in 1995: 7 wins: 6 wins and £202,278 at 3 and 4 years inc. -

Outside Covers

YARRADALE STUD 2013 YEARLING SALE 12.00PM SUNDAY 19 MAY O’BRIEN ROAD, GIDGEGANNUP, WESTERN AUSTRALIA FROST GIANT HE’S COMING New to Western Australia in 2013 A son of GIANT’S CAUSEWAY, just like champion sire, SHAMARDAL. From the STORM CAT sireline, just like successful WA sire MOSAYTER - sire of MR MOET, TRAVINATOR, ROMAN KNOWS etc This durable, tough Group 1 winner, won from 2 years through to 5 years and was a top class performer on both turf and dirt. In his freshman year in 2012 he was fourth leading first crop sire in America!! (ahead of Big Brown, Street Boss etc) • Ranked number 1 by % winners to runners – 80% • Ranked number 1 by Stakes horses to runners – 27% • All time leading money earnings for a first crop sire in America’s North East. With his first crop of 2YO’s in 2012 he sired: • 15 runners for 12 individual 2YO winners! • 4 of those were 2YO stakes horses! • Average earnings of over $50,000 for every 2YO! Continuing on from what has been a wonderful year on the racetrack for our Yarradale Stud graduates, we take great pleasure in presenting to you our 2013 Yarradale Stud Yearling Sale catalogue. After four successful editions of the on farm sale, we are now seeing some fantastic results and stories coming out of these sales. Not only have the previous on farm sales been a great day out with wonderful crowds in attendance, these sales are now proving to be a great source of winners. Obviously our aim is to sell yearlings that go on and perform and we have been thrilled to see the graduates of our previous sales really hitting their straps in recent times. -

A Social and Cultural History of the New Zealand Horse

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE NEW ZEALAND HORSE CAROLYN JEAN MINCHAM 2008 E.J. Brock, ‘Traducer’ from New Zealand Country Journal.4:1 (1880). A Social and Cultural History of the New Zealand Horse A Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Massey University, Albany, New Zealand Carolyn Jean Mincham 2008 i Abstract Both in the present and the past, horses have a strong presence in New Zealand society and culture. The country’s temperate climate and colonial environment allowed horses to flourish and accordingly became accessible to a wide range of people. Horses acted as an agent of colonisation for their role in shaping the landscape and fostering relationships between coloniser and colonised. Imported horses and the traditions associated with them, served to maintain a cultural link between Great Britain and her colony, a characteristic that continued well into the twentieth century. Not all of these transplanted readily to the colonial frontier and so they were modified to suit the land and its people. There are a number of horses that have meaning to this country. The journey horse, sport horse, work horse, warhorse, wild horse, pony and Māori horse have all contributed to the creation of ideas about community and nationhood. How these horses are represented in history, literature and imagery reveal much of the attitudes, values, aspirations and anxieties of the times. -

Die Jäger in Berlin

MITTEILUNGSBLATT DES LJV BERLIN 56. JAHRGANG DIE JÄGER IN BERliN 5 | September – Oktober 2018 www.ljv-berlin.de DER HEIDETERRIER: EIN SPEZIAlisT > SEITE 5 Internationale Berlin Ladies Jagdkonferenz Shooting Day > Seite 9 > Seite 12 EiNLADUNG ZUM SCHIESSEN DRÜCKJAGD SPEZIAL 2018 DER LANDESJAGDVERBÄNDE BERliN UND BRANDENBURG Das Schießen dient der Vorbereitung auf die anstehende Drückjagdsaison, bei dem verschiedene Jagdsituationen simuliert und trainiert werden können, um einen sicheren und waidgerechten Schuss auf der Jagd zu gewährleisten. Zugelassen sind Repetierbüchsen, Kipplaufwaffen und Selbstladebüchsen. Wiederholungen sind selbstverständlich möglich und sol- len den Übungseffekt erhöhen. Es werden DJV-Wildscheiben und Fotoscheiben mit jagdlicher Wertung genutzt. Veranstalter: Landesjagdverband Berlin e.V. und Landesjagdverband Brandenburg e.V. Schirmherr: Frankonia Schießleitung: Jürgen Rosinsky, Michael Pralat, Uwe Rosenow und Thomas Werdnik Austragungsort: DEVA Schießanlage Wannsee, Stahnsdorfer Damm 12, 14109 Berlin TERMIN: 08. SEPTEMBER 2018 BEGINN: 14.00 UHR | MELDESCHLUSS: 14.30 UHR | ENDE: 17.00 UHR StaND: A UND B Startgeld: €20,– inklusive einer Wiederholung, weitere Wiederholungen je €5,– Anmeldung: Am Austragungsort bei der Schießleitung, gültiger Jahresjagdschein oder gleichwertiger Versicherungsnachweis ist vorzulegen. Gäste sind herzlich willkommen. Es werden folgende Büchsendisziplinen geschossen (Änderungen vorbehalten): 1. 5 Schüsse auf 3 Wildscheiben auf laufende Scheibe, breite Schneise und langsamer Lauf, Rechts- und Linkslauf, auf 50m. 2. 5 Schüsse auf Wildscheiben Bock, Fuchs und Frischling auf 50 m, Anschlag sitzend. 3. 5 Schuss auf eine Wildscheibe Überläufer stehend angestrichen am Schießstock. Zugelassen sind alle Büchsenkaliber. Zur Vorbereitung auf die Drückjagd sollten Kaliber ab 6,5 mm zugelassen auf alles Schalenwild (2000 Joule) genutzt werden. Pro Stand steht ein Schießlehrer als Einweiser und Aufsicht zur Verfügung. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 8/24/08 • PAGE 2 of 17 TDN Feature Presentation

HEADLINE THREE CHIMNEYS NEWS The Idea is Excellence. For information about TDN, War Chant’s WAR MONGER Runs call 732-747-8060. nd Game 2 in Bernard Baruch (G2) www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SUNDAY, AUGUST 24, 2008 TDN Feature Presentation ROCK SOLID It was Group 1 win number five at Newmarket yes- G1 TRAVERS STAKES terday as Susan Magnier and Michael Tabor=s Duke of Marmalade (Ire) (Danehill) ground out a 3/4-length suc- cess in the rerouted G1 Juddmonte International S. Following a gruelling fight in the G1 King George VI and Queen Elizabeth S. at Ascot July 26 and two flights from Ireland due to York=s abandonment Tuesday, KINGMAMBO Ballydoyle=s juggernaut would have been excused for not wanting to roll up his sleeves again here, but that MAMBO IN SEATTLE IS 2nd IN was not the case. Jockey Johnny Murtagh asked him GRADE 1 TRAVERS S. BY A WHISKER! to stretch when he hit the front three furlongs out, and the ADuke@ had too many guns for Phoenix Tower TRAVERS NEARLY A SPLIT DECISION (Chester House) at the finish. New Approach (Ire) (Gali- Jockey Robby Albarado knows Travers heartbreak. leo {Ire}) failed to provide the much-anticipated match, Aboard Grasshopper when he was narrowly defeated and was a further 2 1/2 lengths back as he stayed on by Street Sense a year ago, the Louisiana native for third after racing too keenly in rear early. Cont. p4 thought he had yesterday=s renewal in the bag, so much WHO’LL BE THE PAC MAN? so that he pumped his fist in A well-matched field of 11 older horses go postward victory as Mambo In Seattle in this afternoon=s $1-million GI Pacific Classic at Del (Kingmambo) raced under Mar and never, arguably, has the race carried such the wire. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Spectacular drama in urban entertainment: the dramatisation of community in popular culture Chaney, David Christopher How to cite: Chaney, David Christopher (1985) Spectacular drama in urban entertainment: the dramatisation of community in popular culture, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10497/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Spectacular Drama in Urban Entertainment; the dramatisation of community in popular culture David Christopher Chaney ABSTRACT This is a study of some of the many types of entertainment that have been called spectacular, of the cultural significance of certain conventions in ways of transforming space and identity. Forms of spectacular drama both require and celebrate urban social relations, they constitute essential parts of the popular cultural landscape. They display an idealisation of ways of picturing collective experience. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production. -

Relational Aesthetics: Creativity in the Inter-Human Sphere

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 RELATIONAL AESTHETICS: CREATIVITY IN THE INTER-HUMAN SPHERE Carl Patow VCU Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Interactive Arts Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5756 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carl A. Patow 2019 All Rights Reserved Relational Aesthetics: Creativity in the Inter-Human Sphere A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Art at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Carl Patow BA Duke University, Durham, NC 1975 MD University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 1979 MPH Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 1996 MBA University of St. Thomas, Minneapolis, MN 2007 Committee: Pamela Taylor Turner Associate Professor Kinetic Imaging, VCU Arts Stephanie Thulin Assistant Chair and Associate Professor Kinetic Imaging, VCU Arts John Freyer Assistant Professor of Cross Disciplinary Media Photography and Film, VCU Arts Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2, 2019 2 Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank my wife, Sue, for her love, encouragement and patience as I fulfilled this life-long dream of a master’s in fine arts degree. I would also like to thank the faculty members of the Department of Kinetic Imaging at VCU for their guidance and inspiration. Pam Turner, Stephanie Thulin and John Freyer, my committee members, were especially helpful in shaping my thesis and artwork.