Relational Aesthetics: Creativity in the Inter-Human Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogo.Pdf

ART HISTORY NATURE FOOD & DRINK CINEMA PHOTOGRAPHY HOBBY SPORT HISTORY OF ART 28 History and Figures of the Church 35 The Contemporary Mosaic 45 Contents The First Civilizations 28 Techniques and Materials Bulgari 45 The Classical World 28 of the Arts 35 Gucci 45 The Early Middle Ages 28 The Romanesque 29 DICTIONARIES OF CIVILIZATION 36 SCRIPTS & ALPHABETS 46 Still Life 21 Goya 24 The Gothic 29 Arabic Alphabet 46 ART The Portrait 21 Leonardo 24 The 1400s 29 Oceania 37 Chinese Script 46 Islamic Art 28 Hieroglyphs 46 Art and Eroticism 21 Manet 24 Africa 38 The Painting of the Serenissima 10 Byzantine and Russian Art 28 Mayan Script 46 Landscape in Art 21 Mantegna 24 Celts, Vikings and Germans 38 The Renaissance 29 Japanese Alphabet 46 The Galleria Farnese Michelangelo 25 China 38 The Late 1500s 29 Hebrew Alphabet 46 of Annibale Carracci 11 GREAT MONOGRAPHS 22 Monet 25 Egypt 38 The Baroque 28 Musée d’Orsay 11 Bosch 22 Perugino 24 Etruscans 38 The Early 1700s 28 CULTURE GUIDES 47 Correggio. The Frescoes in Parma 11 Caravaggio 22 Piero della Francesca 24 Japan 38 The Age of the Revolutions 28 Archaeology 47 Botticelli 11 Cézanne 22 Raphael 25 Greece 38 Romanticism 28 Art 47 Goya 11 Gauguin 22 Rembrandt 24 India 38 The Age of Impressionism 28 Artistic Prints 47 Museum of Museums 11 Giotto 22 Renoir 24 Islam 38 American Art 28 Design 47 Goya 22 Tiepolo 24 Maya and Aztec 38 Nicolas Poussin Ethnic Art 47 Leonardo da Vinci 22 Tintoretto 24 The Avant-Gardes 29 Mesopotamy 38 Catalogue raisonné of the Paintings 12 Graphic Design 47 Michelangelo 22 Titian 25 Contemporary Art 28 Rome 38 Photography, Cinema, Design 28 Impressionism 47 Palladio. -

Untitled Leaves Clues About the Man Whose Portrait He Captured

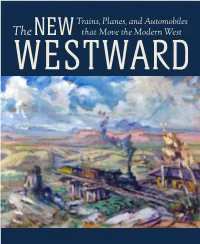

October 15, 2016–February 12, 2017 Published on the occasion of the exhibition The New Westward: Trains, Planes, and Automobiles that Move the Modern West organized by the Tucson Museum of Art and Historic Block October 15, 2016–February 12, 2017 ©Tucson Museum of Art and Historic Block CURATOR AND AUTHOR: Christine C. Brindza, James and Louise Glasser Curator of Art of the American West, Tucson Museum of Art FOREWORD: Jeremy Mikolajczak, Chief Executive Officer EDITOR: Katie Perry DESIGN: Melina Lew PRINTER: Arizona Lithographers, Tucson, Arizona ISBN: 978-0-911611-21-2 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2016947252 Tucson Museum of Art and Historic Block 140 North Main Avenue Tucson, Arizona 85701 tucsonmuseumofart.org FRONT COVER: Ray Strang (1893–1957), Train Station, c.1950, oil on paper, 14 x 20 in. Collection of the Tucson Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Dorothy Gibson. 1981.50.20 CONTENTS 07 Foreword Jeremy Mikolajczak, Chief Executive Officer 09 Author Acknowledgements 11 The New Westward: Trains, Planes, and Automobiles that Move the Modern West Christine C. Brindza 13 Manifest Destiny, Westward Expansion, and Prequels to Western Imagery in the Modern Era 19 Trains: A Technological Sublime 27 Airplanes: Redefining Western Expanses 33 The Automobile: The Great Innovation 39 Works Represented 118 Bibliography 120 Exhibition and Catalogue Sponsors FOREWORD The Tucson Museum of Art is proud to present The New Westward: Trains, Planes, and Automobiles that Move the Modern West, a thematic exhibition examining the role transportation technology has played in the American West in visual art. In today’s fast-moving, digitally-connected world, it is easy to overlook the formative years of travel and the massive overhauls that were achieved for railroads, highways, and aircraft to reach the far extended terrain of the West. -

Preserving New Media Art: Re-Presenting Experience

Preserving New Media Art: Re-presenting Experience Jean Bridge Sarah Pruyn Visual Arts & Interactive Arts and Science, Theatre Studies, University of Guelph, Brock University Guelph, Canada St. Catharines, Canada [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords There has been considerable effort over the past 10 years to define methods for preservation, documentation and archive of new Art, performance art, relational art, interactive art, new media, art media artworks that are characterized variously as ephemeral, preservation, archive, art documentation, videogame, simulation, performative, immersive, participatory, relational, unstable or representation, experience, interaction, aliveness, virtual, technically obsolete. Much new media cultural heritage, authorship, instrumentality consisting of diverse and hybrid art forms such as installation, performance, intervention, activities and events, are accessible to 1. INTRODUCTION us as information, visual records and other relatively static This investigation has evolved from our interest in finding documents designed to meet the needs of collecting institutions documentation of artwork by artists who produce technologically and archives rather than those of artists, students and researchers mediated installations, performances, interventions, activities and who want a more affectively vital way of experiencing the artist’s events - the nature of which may be variously limited in time or creative intentions. It is therefore imperative to evolve existing duration, performance based, -

View and Download the File

THROUGH THE BARRICADES DECEMBER 3RD 20I5 > JANUARY I0TH 20I6 FABBRICA DEL VAPORE, MILAN Promoted by BJCEM, Biennale des jeunes créateurs 2 de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée Municipality of Milan Board of Directors Helen Andreou, Selim Birsel, Keith Borg, Isabelle Bourgeois, Rita Canarezza, Miguel Cascales Tarazona, Petros Dymiotis, Claudio Grillone, Paulo Gouveia, France Irrmann, BJCEM - BIENNALE DES JEUNES CRÉATEURS Maria del Gozo Merino Sanchez, Nina Mudrinic Milovanovic, Said Murad, Abdo Nawar, Ksenija Orelj, Leonardo Punginelli, DE L’EUROPE ET DE LA MÉDITERRANÉE Mohamed Rafik Khalil, Raphael Sage, Ana Savjak, Jernej Skof, Ibrahim Spahić, Carlo Testini, Eleni Tsevekidou, Luis Verde Godoy BJCEM Members Arci Bari (Italy), Arci Emilia Romagna (Italy), Arci Lazio (Italy), Arci President Milano (Italy), Arci Nazionale (Italy), Arci Pescara (Italy), Arci Regionale Emilia Romagna (Italy), Arci Regionale Liguria (Italy), Arci Regionale Dora Bei Puglia (Italy), Arci Regionale Sardegna (Italy), Arci Regionale Sicilia (Italy), Arci Torino (Italy), Atelier d’Alexandrie (Egypt), Ayuntamiento de General Secretary Madrid (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Malaga (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Murcia (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Salamanca (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Sevilla Federica Candelaresi (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Valencia (Spain), Centar za Savremenu Umetnost Strategie Art (Serbia), Città di Torino (Italy), Città di Venezia (Italy), City Treasurer of Thessaloniki (Greece), Clube Português de Artes e Ideias (Portugal), Helen Andreou Comune di Ancona (Italy), Comune -

Participatory Art

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AESTHETICS, Michael Kelly, Editor-in-Chief (Oxford University Press, 2014) Participatory Art. In recent decades, contemporary visual and performance art created through a participatory process has drawn increasing attention. Its value is the subject of considerable debate, including a lively conversation around the ethics and aesthetics of the practice as well as the vocabulary best suited to describe and critique it. Participatory art exists under a variety of overlapping headings, including interactive, relational, cooperative, activist, dialogical, and community-based art. In some cases, participation by a range of people creates an artwork, in others the participatory action is itself described as the art. So the conceptual photographer Wendy Ewald gave cameras and photography training to a group of children in a village in India, who, in turn, depicted their community, and the resulting photography show was considered participatory art. On the other hand, the multimedia visual artist Pedro Lasch collaborated with a group of “Sonidero” DJ’s on a party at an art center in Mexico City, and he called the social interactions leading to, and including, the public event an artwork co-authored by a range of participants—including the people who simply showed up for the event. Click to view larger Tatlin’s Whisper #5, 2008 (mounted police, crowd control techniques, audience), Tania Bruguera. Photo by Sheila Burnett. courtesy of tate modern Of course participation in the collective creation of art is not new. Across the globe, throughout recorded history people have participated in the creation of art—from traditional music and dance to community festivals to mural arts. -

Participatory Art and Creative Audience Engagement

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2011 Practices of Fluid Authority: Participatory Art and Creative Audience Engagement Smolinski, Richard Smolinski, R. (2011). Practices of Fluid Authority: Participatory Art and Creative Audience Engagement (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/22585 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48892 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Practices of Fluid Authority: Participatory Art and Creative Audience Engagement by Richard Smolinski A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ART CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER 2011 Richard Smolinski 2011 i The author of this thesis has granted the University of Calgary a non-exclusive license to reproduce and distribute copies of this thesis to users of the University of Calgary Archives. Copyright remains with the author. Theses and dissertations available in the University of Calgary Institutional Repository are solely for the purpose of private study and research. They may not be copied or reproduced, except as permitted by copyright laws, without written authority of the copyright owner. Any commercial use or re-publication is strictly prohibited. The original Partial Copyright License attesting to these terms and signed by the author of this thesis may be found in the original print version of the thesis, held by the University of Calgary Archives. -

Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics Author(S): Claire Bishop Source: October, Vol

Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics Author(s): Claire Bishop Source: October, Vol. 110 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 51-79 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3397557 Accessed: 19/10/2010 19:54 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics CLAIRE BISHOP The Palais de Tokyo On the occasion of its opening in 2002, the Palais de Tokyo immediately struck the visitor as different from other contemporary art venues that had recently opened in Europe. -

TA 4.3 00 FM.Qxd

TA 4.3_01_art_Smith.qxd 12/8/06 10:59 AM Page 169 Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research Volume 4 Number 3. © Intellect Ltd 2006. Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/tear.4.3.169/1 Art games: Interactivity and the embodied gaze Graham Coulter-Smith Southampton Solent University Elizabeth Coulter-Smith Staffordshire University Abstract Keywords One of the most salient differences between fine art and new media art lies in art games the possibility for interactivity. Interactivity is not simply an inherent quality of art into life new media, it also relates to a crucial ethico-aesthetic premise informing decon- creativity structive art from Dada and Surrealism through radical art of the 1960s and installation art 1970s and into the present. The ethico-aesthetic premise in question concerns interactive art breaking down the barrier between the viewer and the work of art and bringing relational aesthetics art into life. More specifically the goal is to bring creativity into everyday life as an antidote to alienation and reification. Whereas new media art finds it rela- tively easy to devise art games that encourage creative involvement on the part of the viewer, fine art is severely hindered in its attempts in this direction by the traditional focus on the artist-genius and the transformation of the artistic prod- uct (whatever its material) into a precious object. It will be shown that creative games exist in fine art but they are for the most part designed by the artist for the artist. This is even the case with the most radical fine artists celebrated at the turn of the millennium such as Rirkrit Tiravanija who Nicolas Bourriaud put forward as a prime instance of so-called relational aesthetics. -

Nicolas Bourriaud Postproduction Culture As Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World 11 Has & Sternberg, New York

NICOLAS BOURRIAUD POSTPRODUCTION CULTURE AS SCREENPLAY: HOW ART REPROGRAMS THE WORLD 11 HAS & STERNBERG, NEW YORK CONTENTS Nicolas Bourriaud PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION Postproduction Publisher: Lukas & Sternberg, New York INTRODUCTION © 2002 Nicolas Bourriaud, Lukas & Sternberg All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. THE USE OF OBJECTS THE USE OF THE PRODUCT FROM MARCEL DUCHAMP First published 2002 (0-9711193-0-9) TO JEFF KOONS Reprinted with new preface 2005 THE FLEA MARKET: THE DOMINANT ART FORM OF THE NINETIES - -,.- •-••.• Editor: Caroline Schneider Translation: Jeanine Herman THE USE OF FORMS Copy Editors: Tatjana Giinthner, Radhika Jones, John Kelsey DEEJAYING AND CONTEMPORARY ART: SIMILAR Design: Sandra Kastl, Markus Weisbeck, surface, Berlin /Frankfurt CONFIGURATIONS Printing and binding: Medialis, Berlin WHEN SCREENPLAYS BECOME FORM: A USER'S GUIDE ISBN 0-9745688-9-9 TO THE WORLD . THE USE OF THE WORLD 69 Lukas & Sternberg PLAYING THE WORLD: REPROGRAMMING SOCIAL FORMS 69 Caroline Schneider HACKING, WORK, AND FREE TIME 1182 Broadway #1602, New York NY 10001 LinienstraBe 159, D-10115 Berlin HOW TO INHABIT GLOBAL CULTURE [email protected], www.lukas-sternberg.com (AESTHETICS AFTER MP3) I PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION Since its initial publication in 2001, Postproduction has been trans- lated into five languages; depending on the translation schedules in various countries, publication either overlapped with or preceded that of another of my books, Esthetique relationnelle (Relational Aesthetics), written five years earlier. The relationship between these two theoret- ical essays has often been the source of a certain misunderstanding, if not malevolence, on the part of a critical generation that knows itself to be slowing down and counters my theories with recitations from "The Perfect American Soft Marxist Handbook" and a few vestiges of Greenbergian catechism. -

C O L L E C T I O N B O

THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA ART CONTEMPORARY T HE COLLECTION BOOK y �� THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA ART CONTEMPORARY ��THE T H E COLLECTIONCOllECtIoN BOOK y BOOK VERLAG DER BUCHHANDLUNG WALTHER KÖNIG, KÖLN 4 5 CONTENTS 6 Acknowledgments by FRANCESCA VON HABSBURG 01 02 03 04 t t t t 10 WAYS BEYOND 72 DIE OR PERFORM 280 T H E A L E P H 354 PRESERVATION OBJECTS by ANDREAS SCHLAEGEL P O T E N T I A L AND REANIMATION FRANCESCA VON HABSBURG by ELKE KRASNY THROUGH in conversation with 88 MONICA BONVICINI CONTEMPORARY ART HANS ULRICH OBRIST 92 CANDICE BREITZ 288 PARADOXES OF AND ARCHITECTURE 97 JANET CARDIFF COLLECTING 22 AI WEIWEI 107 MAURIZIO CATTELAN FRANCESCA VON HABSBURG 361 MONUMENTAL 28 DOUG AITKEN 110 CHEN QUILIN in conversation with by MARK WIGLEY 34 DARREN ALMOND 116 ANETTA MONA CHISA & PETER PAKESCH 40 KUTLUĞ ATAMAN LUCIA TKÁČOVÁ 366 JULIAN ROSEFELDT 52 FIONA BANNER 120 CYBERMOHOLLA HUB 292 RIVANE NEUENSCHWANDER 376 THOMAS RUFF 56 JOHN BOCK 125 EMANUEL DANESCH & 298 JUN NGUYEN-HATSUSHIBA 378 RITU SARIN & DAVID RYCH 302 CARSTEN NICOLAI TENZING SONAM 129 DON’T TRUST ANYONE 308 OLAF NICOLAI 383 HANS SCHABUS OVER THIRTY 314 PAUL PFEIFFER 390 CHRISTOPH SCHLINGENSIEF 138 OLAFUR ELIASSON 320 WALID RAAD / 398 GREGOR SCHNEIDER 152 ELMGREEN & DRAGSET THE ATLAS GROUP 406 ALLAN SEKULA 160 MARIO GARCÍA TORRES 330 RAQS MEDIA COLLECTIVE 414 NEDKO SOLAKOV 164 ISA GENZKEN 336 JASON RHOADES 419 MONIKA SOSNOWSKA 168 DOUGLAS GORDON 340 PIPILOTTI RIST 422 THOMAS STRUTH 172 FLORIAN HECKER 344 MATTHEW RITCHIE 426 DO HO SUH 176 CARSTEN HÖLLER 430 CATHERINE SULLIVAN 181 TERESA -

Gianni Motti

TRANSFERT Publisher TRANSFERT Editor MARC-OLIVIER WAHLER ART DANS L’ESPACE URBAIN KUNST IM URBANEN RAUM ART IN URBAN SPACE No 10 ESS Biel-Bienne CH 17 06 - 31 08 2000 «I LOOKEDATTHE CITY AND I SAW NOTHING» -F DE 8 INTRODUCTION (F) 28 MARC-OLIVIER WAHLER 176 MARC-OLIVIER WAHLER 320 MARC-OLIVIER WAHLER 14 EINFÜHRUNG (D) “J’AI REGARDÉ VERS LA VILLE “ICH SCHAUTE AUF DIE STADT “I LOOKED AT THE CITY AND ET JE N’AI RIEN VU” UND SAH NICHTS” I SAW NOTHING” 20 INTRODUCTION (E) 36 JOSHUA DECTER 184 JOSHUA DECTER 328 JOSHUA DECTER COMMUNICATION-VILLE KOMMUNIKATION STADT COMMUNICATION CITY 46 JEAN-CHARLES MASSÉRA 194 JEAN-CHARLES MASSÉRA 338 JEAN-CHARLES MASSÉRA PUISSE LE PROCESSUS GLOBAL MÖGE DER GLOBALE AKKUMULATIONS- MAY THE GLOBAL PROCESS OF D’ACCUMULATION TREMBLER PROZESS VOR EINER REVOLUTION DER ACCUMULATION TREMBLE AT THE À L’IDÉE D’UNE RÉVOLUTION DES BENUTZER ERZITTERN (MANIFEST FÜR IDEA OF A USERS’ REVOLUTION USAGERS (MANIFESTE POUR DIE (MANIFESTO FOR CONSCIOUSNESS LA CONSCIENTISATION DE LA BEWUSSTMACHUNG DES DEVELOPMENT ABOUT THE USER CONDITION USAGÈRE) BENUTZERDASEINS) CONDITION) 60 OLIVIER MOSSET 208 OLIVIER MOSSET 350 OLIVIER MOSSET INFORMATION TRANSFER INFORMATION TRANSFER INFORMATION TRANSFER 66 MARTIN CONRADS 214 MARTIN CONRADS 356 MARTIN CONRADS COLORIS GLOCAL “GLOKALKOLORIT” GLOCAL COLOR 74 FRANK PERRIN 222 FRANK PERRIN 364 FRANK PERRIN LE JOGGER, HÉROS DE LA VIE DER JOGGER, HELD DES THE JOGGER, HERO OF POSTMODERNE POSTMODERNEN LEBENS POSTMODERN LIFE 82 LORI HERSBERGER 230 OLIVIER BLANCKART 372 PETER LAND 88 OLIVIER MOSSET 236 JONATHAN -

Visual Art and Social Structure: the Social Semiotics of Relational Art

VCJ12210.1177/1470357212471595Visual Communication 4715952013 visual communication ARTICLE Visual art and social structure: the social semiotics of relational art HOWARD RILEY Swansea Metropolitan University, Wales ABSTRACT This article elaborates the dialectical relationship between visual art forms and the social structures in which they are produced, by extending Robert Witkin’s taxonomy first presented in his 1995 book Art and Social Structure. Witkin tracked the history of visual art from pre-modern times, for which he invented the label invocational art, to the advent of Modernism, described in terms of evocational and then provocational art. The article then extrapo- lates from Witkin’s model to include post-Modernism, for which the author’s term revocational art has been coined, and goes on to discuss Nicolas Bourriaud’s concept of Altermodernism, his term for describing the relation- ship between contemporary art practices and the social conditions of today, for which the author suggests an alternative – convocational art – a synonym for Bourriaud’s term relational art. The article concludes with a demonstra- tion that social semiotic theory can be a powerful tool for the analysis of relational art. KEYWORDS convocational art • relational art • revocational art • systemic-functional semiotics TYPES OF SOCIAL STRUCTURES AND RELATED ARTFORMS In his book Art and Social Structure, Robert Witkin (1995) identified three distinct types of social structure, and proposed three types of art forms which correspond with those structures. These have been elaborated elsewhere (Riley, 2004), and so here I shall adumbrate his argument: A co-actional structure, Witkin argued, describes social relations in which each member plays a pre-determined role.