Toxicity of Bupropion Overdose Compared with Selective Serotonin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WELLBUTRIN SR Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION psychosis, hallucinations, paranoia, delusions, homicidal ideation, These highlights do not include all the information needed to use aggression, hostility, agitation, anxiety, and panic, as well as suicidal WELLBUTRIN SR safely and effectively. See full prescribing ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. Observe patients information for WELLBUTRIN SR. attempting to quit smoking with bupropion for the occurrence of such symptoms and instruct them to discontinue bupropion and contact a WELLBUTRIN SR (bupropion hydrochloride) sustained-release tablets, healthcare provider if they experience such adverse events. (5.2) for oral use • Initial U.S. Approval: 1985 Seizure risk: The risk is dose-related. Can minimize risk by gradually increasing the dose and limiting daily dose to 400 mg. Discontinue if WARNING: SUICIDAL THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIORS seizure occurs. (4, 5.3, 7.3) See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. • Hypertension: WELLBUTRIN SR can increase blood pressure. Monitor blood pressure before initiating treatment and periodically during • Increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, treatment. (5.4) adolescents and young adults taking antidepressants. (5.1) • Activation of mania/hypomania: Screen patients for bipolar disorder and • Monitor for worsening and emergence of suicidal thoughts and monitor for these symptoms. (5.5) behaviors. (5.1) • Psychosis and other neuropsychiatric reactions: Instruct patients to contact a healthcare professional if such reactions occur. (5.6) --------------------------- INDICATIONS AND USAGE ---------------------------- • Angle-closure glaucoma: Angle-closure glaucoma has occurred in WELLBUTRIN SR is an aminoketone antidepressant, indicated for the patients with untreated anatomically narrow angles treated with treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). (1) antidepressants. -

Concomitant Drugs Associated with Increased Mortality for MDMA Users Reported in a Drug Safety Surveillance Database Isaac V

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Concomitant drugs associated with increased mortality for MDMA users reported in a drug safety surveillance database Isaac V. Cohen1, Tigran Makunts2,3, Ruben Abagyan2* & Kelan Thomas4 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) is currently being evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). If MDMA is FDA-approved it will be important to understand what medications may pose a risk of drug– drug interactions. The goal of this study was to evaluate the risks due to MDMA ingestion alone or in combination with other common medications and drugs of abuse using the FDA drug safety surveillance data. To date, nearly one thousand reports of MDMA use have been reported to the FDA. The majority of these reports include covariates such as co-ingested substances and demographic parameters. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was employed to uncover the contributing factors to the reported risk of death among MDMA users. Several drug classes (MDMA metabolites or analogs, anesthetics, muscle relaxants, amphetamines and stimulants, benzodiazepines, ethanol, opioids), four antidepressants (bupropion, sertraline, venlafaxine and citalopram) and olanzapine demonstrated increased odds ratios for the reported risk of death. Future drug–drug interaction clinical trials should evaluate if any of the other drug–drug interactions described in our results actually pose a risk of morbidity or mortality in controlled medical settings. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) is currently being evaluated by the Food and Drug Adminis- tration (FDA) for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). During the past two decades, “ecstasy” was illegally distributed and is purported to contain MDMA, but because the market is unregulated this “ecstasy” may actually contain adulterants or no MDMA at all1. -

MEDICATION GUIDE WELLBUTRIN® (WELL Byu-Trin) (Bupropion Hydrochloride) Tablets

NDA 018644/S-041 NDA 020358/S-048 Page 6 MEDICATION GUIDE WELLBUTRIN® (WELL byu-trin) (bupropion hydrochloride) Tablets Read this Medication Guide carefully before you start using WELLBUTRIN and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking with your doctor about your medical condition or your treatment. If you have any questions about WELLBUTRIN, ask your doctor or pharmacist. IMPORTANT: Be sure to read the three sections of this Medication Guide. The first section is about the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions with antidepressant medicines; the second section is about the risk of changes in thinking and behavior, depression and suicidal thoughts or actions with medicines used to quit smoking; and the third section is entitled “What Other Important Information Should I Know About WELLBUTRIN?” Antidepressant Medicines, Depression and Other Serious Mental Illnesses, and Suicidal Thoughts or Actions This section of the Medication Guide is only about the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions with antidepressant medicines. Talk to your, or your family member’s, healthcare provider about: • all risks and benefits of treatment with antidepressant medicines • all treatment choices for depression or other serious mental illness What is the most important information I should know about antidepressant medicines, depression and other serious mental illnesses, and suicidal thoughts or actions? 1. Antidepressant medicines may increase suicidal thoughts or actions in some children, teenagers, and young adults within the first few months of treatment. 2. Depression and other serious mental illnesses are the most important causes of suicidal thoughts and actions. -

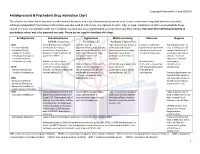

Antidepressant & Psychedelic Drug Interaction Chart

Copyright Psychedelic School 8/2020 Antidepressant & Psychedelic Drug Interaction Chart This chart is not intended to be used to make medical decisions and is for informational purposes only. It was constructed using data whenever possible, although extrapolation from known information was also used to inform risk. Any decision to start, stop, or taper medication and/or use psychedelic drugs should be made in conjunction with your healthcare provider(s). It is recommended to not perform any illicit activity. This chart the intellectual property of psychedelic school and is for personal use only. Please do not copy or distribute this chart. Antidepressant Phenethylamines Tryptamines MAOI-containing Ketamine Ibogaine -MDMA, mescaline -Psilocybin, LSD -Ayahuasca, Syrian Rue SSRIs Taper & discontinue at least 2 Consider taper & Taper & discontinue at least 2 Has been studied and Taper & discontinue at · Paroxetine (Paxil) weeks prior (all except discontinuation at least 2 weeks weeks prior (all except found effective both with least 2 weeks prior (all · Sertraline (Zoloft) fluoxetine) or 6 weeks prior prior (all except fluoxetine) or 6 fluoxetine) or 6 weeks prior and without concurrent except fluoxetine) or 6 · Citalopram (Celexa) (fluoxetine only) due to loss of weeks prior (fluoxetine only) (fluoxetine only) due to use of antidepressants weeks prior (fluoxetine · Escitalopram (Lexapro) psychedelic effect due to potential loss of potential risk of serotonin only) due to risk of · Fluxoetine (Prozac) psychedelic effect syndrome additive QTc interval · Fluvoxamine (Luvox) MDMA is unable to cause Recommended prolongation, release of serotonin when the Chronic antidepressant use may Life threatening toxicities can to be used in conjunction arrhythmias, or SPARI serotonin reuptake pump is result in down-regulation of occur with these with oral antidepressants cardiotoxicity · Vibryyd (Vilazodone) blocked. -

Phd Thesis Project: Pharmacological and Toxicological Investigations of New Psychoactive Substances, Supervised by Prof

PHARMACOLOGICAL AND TOXICOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF NEW PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Dino Lüthi aus Rüderswil, Bern Basel, 2018 Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentenserver der Universität Basel edoc.unibas.ch Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung-Nicht kommerziell 4.0 International Lizenz (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de). Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von Prof. Stephan Krähenbühl, Prof. Matthias E. Liechti und Prof. Anne Eckert. Basel, den 26.06.2018 Prof. Martin Spiess Dekan der Philosophisch- Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät PHARMACOLOGICAL AND TOXICOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF NEW PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES “An adult must make his own decision as to whether or not he should expose himself to a specific drug, be it available by prescription or proscribed by law, by measuring the potential good and bad with his own personal yardstick.” ― Alexander Shulgin, Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story. PREFACE This thesis is split into a pharmacology part and a toxicology part. The pharmacology part consists of investigations on the monoamine transporter and receptor interactions of traditional and newly emerged drugs, mainly stimulants and psychedelics; the toxicology part consists of investigations on mechanisms of hepatocellular toxicity of synthetic cathinones. All research described in this thesis has been published in peer-reviewed journals, and was performed between October 2014 and June 2018 in the Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology at the Department of Biomedicine of the University Hospital Basel and University of Basel, and partly at the pRED Roche Innovation Center Basel at F. -

MEDICATION GUIDE Bupropion Hydrochloride Extended-Release

MEDICATION GUIDE BuPROPion Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets, USP (SR) (byoo-PROE-pee-on) Read this Medication Guide carefully before you start taking bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR) and each time you get a refill. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking with your healthcare provider about your medical condition or your treatment. If you have any questions about bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR), ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist. IMPORTANT: Be sure to read the three sections of this Medication Guide. The first section is about the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions with antidepressant medicines; the second section is about the risk of changes in thinking and behavior, depression and suicidal thoughts or actions with medicines used to quit smoking; and the third section is entitled “What Other Important Information Should I Know About Bupropion Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets (SR)?” Antidepressant Medicines, Depression and Other Serious Mental Illnesses, and Suicidal Thoughts or Actions This section of the Medication Guide is only about the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions with antidepressant medicines. Talk to your healthcare provider or your family member’s healthcare provider about: • all risks and benefits of treatment with antidepressant medicines • all treatment choices for depression or other serious mental illness What is the most important information I should know about antidepressant medicines, depression and other serious mental illnesses, and suicidal thoughts or actions? 1. Antidepressant medicines may increase suicidal thoughts or actions in some children, teenagers, or young adults within the first few months of treatment. -

Appendix-2Final.Pdf 663.7 KB

North West ‘Through the Gate Substance Misuse Services’ Drug Testing Project Appendix 2 – Analytical methodologies Overview Urine samples were analysed using three methodologies. The first methodology (General Screen) was designed to cover a wide range of analytes (drugs) and was used for all analytes other than the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs). The analyte coverage included a broad range of commonly prescribed drugs including over the counter medications, commonly misused drugs and metabolites of many of the compounds too. This approach provided a very powerful drug screening tool to investigate drug use/misuse before and whilst in prison. The second methodology (SCRA Screen) was specifically designed for SCRAs and targets only those compounds. This was a very sensitive methodology with a method capability of sub 100pg/ml for over 600 SCRAs and their metabolites. Both methodologies utilised full scan high resolution accurate mass LCMS technologies that allowed a non-targeted approach to data acquisition and the ability to retrospectively review data. The non-targeted approach to data acquisition effectively means that the analyte coverage of the data acquisition was unlimited. The only limiting factors were related to the chemical nature of the analyte being looked for. The analyte must extract in the sample preparation process; it must chromatograph and it must ionise under the conditions used by the mass spectrometer interface. The final limiting factor was presence in the data processing database. The subsequent study of negative MDT samples across the North West and London and the South East used a GCMS methodology for anabolic steroids in addition to the General and SCRA screens. -

BUPROPION SUSTAINED RELEASE (SR) 150Mg

Patient Guide: Tobacco Cessation Therapy BUPROPION SUSTAINED RELEASE (SR) 150mg Medication together with behavioral counseling gives you the best chance of quitting smoking What does this medication do? Bupropion is a non-nicotine aid to help you quit smoking by reducing withdrawal symptoms. It can be taken alone or with a nicotine replacement product (generally with a nicotine gum or lozenge). Bupropion is recommended along with a tobacco cessation program in order to provide you with additional support and educational materials. How do I use it? Set a date when you intend to stop smoking (quit date). The medicine needs to be started 1-2 weeks before that date. Take 1 tablet daily for 3 days, then increase to 1 tablet twice daily if you tolerate it. Take at a similar time each day, allowing approximately 8 hours in between doses. Don’t take bupropion past 5pm to avoid trouble sleeping. This medicine may be taken for 7-12 weeks and in some cases up to 6 months. Discuss with your provider if you need to be treated longer than 12 weeks. This medicine may be taken with or without food. If you miss a dose, skip the missed dose and take the next dose at the regular time. If you slip up and smoke while taking the medicine, don’t give up. Continue to take the medicine and try not to smoke. What are the possible side effects? It may take a few weeks to feel the full benefits of this medicine. Common side effects include insominia, dry mouth and constipation. -

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (Also Belong to Psychiatric Medication Category) • Codeine (In 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • codeine (in 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No. 1/2/3/4, Fiorinal® C, Benzodiazepines Codeine Contin, etc.) • heroin • alprazolam (Xanax®) • hydrocodone (Hycodan®, etc.) • chlordiazepoxide (Librium®) • hydromorphone (Dilaudid®) • clonazepam (Rivotril®) • methadone • diazepam (Valium®) • morphine (MS Contin®, M-Eslon®, Kadian®, Statex®, etc.) • flurazepam (Dalmane®) • oxycodone (in Oxycocet®, Percocet®, Percodan®, OxyContin®, etc.) • lorazepam (Ativan®) • pentazocine (Talwin®) • nitrazepam (Mogadon®) • oxazepam ( Serax®) Alcohol • temazepam (Restoril®) Inhalants Barbiturates • gases (e.g. nitrous oxide, “laughing gas”, chloroform, halothane, • butalbital (in Fiorinal®) ether) • secobarbital (Seconal®) • volatile solvents (benzene, toluene, xylene, acetone, naptha and hexane) Buspirone (Buspar®) • nitrites (amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite and cyclohexyl nitrite – also known as “poppers”) Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • chloral hydrate • zopiclone (Imovane®) Other • GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) • Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM STIMULANTS Amphetamines Caffeine • dextroamphetamine (Dexadrine®) Methelynedioxyamphetamine (MDA) • methamphetamine (“Crystal meth”) (also has hallucinogenic actions) • methylphenidate (Biphentin®, Concerta®, Ritalin®) • mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall XR®) 3,4-Methelynedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) (also has hallucinogenic actions) Cocaine/Crack -

Development of Hyperprolactinemia Induced by the Addition of Bupropion to Venlafaxine XR Treatment

Case Report Bezmialem Science 2018; 6: 150-2 DOI: 10.14235/bs.2018.1119 Development of Hyperprolactinemia Induced by the Addition of Bupropion to Venlafaxine XR Treatment Alperen KILIÇ , Ahmet ÖZTÜRK , Erdem DEVECİ , İsmet KIRPINAR Department of Psychiatry, Bezmialem Vakif University School of Medicine, İstanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT Hyperprolactinemia is characterized by abnormally increased serum prolactin levels. Menstrual irregularities and hyperprolactinemia can be caused by a variety of medical conditions as well as due to the use of some psychopharmacological drugs, namely antipsychotics; it can also develop during antidepressant treatment. Bupropion is an antidepressant functioning via the inhibition of noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake. The endocrine and sexual adverse events of this agent are rare. In the literature, only one case reporting hy- perprolactinemia or galactorrhea caused by bupropion use is available. Here, we present the case of a patient diagnosed with depressive disorder and receiving venlafaxine, who developed hyperprolactinemia and oligomenorrhea after the addition of bupropion the ongoing treatment and showed serum prolactin levels decreased to normal ranges shortly after the discontinuation of bupropion. Keywords: Bupropion, venlafaxiane, hyperprolactinemia Introduction Mainly associated with antipsychotic use, hyperprolactinemia and menstrual irregularities can be seen as a result of antidepressant use. Reportedly, monoaminooxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increase prolactin levels (1). The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline, fluvoxamine, fluoxetine or serotonin, and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, such as venlafaxine XR and duloxetine, have been shown to be associated with hyperprolactinemia and/or galactorrhea in some cases (2, 3). In these cases, the serotonergic mechanism is commonly attributed as the underlying cause of hyperprolactinemia and/or galactor- rhea. -

Tcas Versus Placebo - New Studies in the Guideline Update

TCAs versus placebo - new studies in the guideline update Comparisons Included in this Clinical Question Amitriptyline vs placebo Clomipramine vs placebo Dosulepin (dothiepin) vs placebo AMSTERDAM2003A LARSEN1989 FERGUSON1994B BAKISH1992B PECKNOLD1976B ITIL1993 BAKISH1992C RAMPELLO1991 MINDHAM1991 BREMNER1995 THOMPSON2001B CLAGHORN1983 CLAGHORN1983B FEIGHNER1979 GELENBERG1990 GEORGOTAS1982A GOLDBERG1980 HICKS1988 HOLLYMAN1988 HORMAZABAL1985 HOSCHL1989 KLIESER1988 LAAKMAN1995 LAPIERRE1991 LYDIARD1997 MYNORSWALLIS1995 MYNORSWALLIS1997 REIMHERR1990 RICKELS1982D RICKELS1985 RICKELS1991 ROFFMAN1982 ROWAN1982 SMITH1990 SPRING1992 STASSEN1993 WILCOX1994 16 Imipramine vs placebo BARGESCHAAPVELD2002 BEASLEY1991B BOYER1996A BYERLEY1988 CASSANO1986 CASSANO1996 CLAGHORN1996A COHN1984 COHN1985 COHN1990A COHN1992 COHN1996 DOMINGUEZ1981 DOMINGUEZ1985 DUNBAR1991 ELKIN1989 ENTSUAH1994 ESCOBAR1980 FABRE1980 FABRE1992 FABRE1996 FEIGER1996A FEIGHNER1980 FEIGHNER1982 FEIGHNER1983A FEIGHNER1983B FEIGHNER1989 FEIGHNER1989A FEIGHNER1989B FEIGHNER1989C FEIGHNER1992B FEIGHNER1993 FONTAINE1994 GELENBERG2002 GERNER1980B HAYES1983 ITIL1983A KASPER1995B KELLAMS1979 LAIRD1993 LAPIERRE1987 LECRUBIER1997B LIPMAN1986 LYDIARD1989 MARCH1990 17 MARKOWITZ1985 MENDELS1986 MERIDETH1983 Nortriptyline vs placebo NANDI1976 GEORGOTAS1986A NORTON1984 KATZ1990 PEDERSEN2002 NAIR1995 PESELOW1989 WHITE1984A PESELOW1989B PHILIPP1999 QUITKIN1989 RICKELS1981 RICKELS1982A RICKELS1987 SCHWEIZER1994 SCHWEIZER1998 SHRIVASTAVA1992 SILVERSTONE1994 SMALL1981 UCHA1990 VERSIANI1989 VERSIANI1990 -

The Efficacy and Toxicity of Bupropion in the Elderly

Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 8 January 2000 The Efficacy ando T xicity of Bupropion in the Elderly William T. Howard M.D., M.S. Johns Hopkins Department of Mental Hygiene Julia K. Warnock M.D., Ph.D. Department of Psychiatry, University of Oklahoma, Tulsa, OK Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/jeffjpsychiatry Part of the Psychiatry Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Howard, William T. M.D., M.S. and Warnock, Julia K. M.D., Ph.D. (2000) "The Efficacy ando T xicity of Bupropion in the Elderly," Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29046/JJP.015.1.004 Available at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/jeffjpsychiatry/vol15/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. The Efficacy and Toxicity of Bupropion in the Elderly William T. Howard,M.D., M.S.l and Julia K.