NSIAD-95-148BR Peace Operations: Update on the Situation in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siege of Sarajevo Endangered Civilians

BALKAN January 8, 2004 Page 6 VIEW FROM THE HAGUE SIEGE OF SARAJEVO ENDANGERED CIVILIANS On 5 December this year, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia sentenced General Stanislav Gali ć to 20 years in prison for spreading terror among the civilian population during the siege of Sarajevo. The city of Sarajevo was under siege for about three and a half years. For almost two years of that time, from September 1992 to August 1994, General Gali ć was the commander of a branch of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS), called the Sarajevo Romanija Corps, or SRK, which had virtually encircled Sarajevo. Parts of the city were controlled by the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Prosecution alleged that the SRK under General Gali ć's command conducted a campaign of sniping and shelling attacks on civilians in Sarajevo. Under international humanitarian law war as such is not considered unlawful. However, certain principles of warfare apply that military commanders must respect. One such principle obliges military commanders to distinguish between military objectives, on the one hand, and civilians, on the other, and not to attack civilians under any circumstances. And yet, the SRK's campaign resulted in a large number of deaths and injuries to civilians. The Tribunal Prosecution alleged that the SRK, under General Gali ć's command deliberately killed and injured civilians in order to terrorize them. Terrorising civilians Terrorising civilians during armed conflict is specifically prohibited by Article 51 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. The former Yugoslavia ratified this protocol in 1978. -

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

Worlds Apart Swanee Hunt Worlds Apart Bosnian Lessons for GLoBaL security Duke university Press Durham anD LonDon 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my partners c harLes ansBacher: “Of course you can.” and VaLerie GiLLen: “Of course we can.” and Mirsad JaceVic: “Of course you must.” Contents Author’s Note xi Map of Yugoslavia xii Prologue xiii Acknowledgments xix Context xxi Part i: War Section 1: Officialdom 3 1. insiDe: “Esteemed Mr. Carrington” 3 2. outsiDe: A Convenient Euphemism 4 3. insiDe: Angels and Animals 8 4. outsiDe: Carter and Conscience 10 5. insiDe: “If I Left, Everyone Would Flee” 12 6. outsiDe: None of Our Business 15 7. insiDe: Silajdžić 17 8. outsiDe: Unintended Consequences 18 9. insiDe: The Bread Factory 19 10. outsiDe: Elegant Tables 21 Section 2: Victims or Agents? 24 11. insiDe: The Unspeakable 24 12. outsiDe: The Politics of Rape 26 13. insiDe: An Unlikely Soldier 28 14. outsiDe: Happy Fourth of July 30 15. insiDe: Women on the Side 33 16. outsiDe: Contact Sport 35 Section 3: Deadly Stereotypes 37 17. insiDe: An Artificial War 37 18. outsiDe: Clashes 38 19. insiDe: Crossing the Fault Line 39 20. outsiDe: “The Truth about Goražde” 41 21. insiDe: Loyal 43 22. outsiDe: Pentagon Sympathies 46 23. insiDe: Family Friends 48 24. outsiDe: Extremists 50 Section 4: Fissures and Connections 55 25. -

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

Bosnia to War, to Dayton, and to Its Slow Peace – European Council On

REPORT BOSNIA TO WAR, TO DAYTON, AND TO ITS SLOW PEACE Carl Bildt January 2021 SUMMARY The international community was gravely unprepared for the conflicts that followed the dissolution of Yugoslavia. In particular, it neglected the challenge of Bosnia. Europe alone was not enough to bring peace, and the United States went from disinterested to disruptive and finally to decisive for a credible peace process. Russia in those days was a constructive actor. The war in Bosnia lasted years longer than it should have more because of the divisions between outside powers than because of the divisions within the country and the region itself. The fundamentals of the Dayton Agreement in 1995 were not too dissimilar from what had been discussed, but not pursued, prior to the outbreak of the war. It is a solution that is closer to the reality of Belgium than to the reality of Cyprus. After the war, many political leaders in Bosnia saw peace as the continuation of the war by other means, which has seriously hampered economic and social progress. Ultimately, it will be difficult to sustain progress for Bosnia or the region without a credible and clear EU accession process. INTRODUCTION It was a quarter of a century ago that the most painful conflict on European soil since the second world war came to an end. Peace agreements are rare birds. Most conflicts end either with the victory of one of the sides or some sort of ceasefire that is rarely followed by a true peace agreement. The map of Europe shows a number of such ‘frozen conflicts’. -

Never Again: International Intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina1

Never again: 1 International intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina July 2017 David Harland2 1 This study is one of a series commissioned as part of an ongoing UK Government Stabilisation Unit project relating to elite bargains and political deals. The project is exploring how national and international interventions have and have not been effective in fostering and sustaining political deals and elite bargains; and whether or not these political deals and elite bargains have helped reduce violence, increased local, regional and national stability and contributed to the strengthening of the relevant political settlement. This is a 'working paper' and the views contained within do not necessarily represent those of HMG. 2 Dr David Harland is Executive Director of the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. He served as a witness for the Prosecution at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in the cases of The Prosecutor versus Slobodan Milošević, The Prosecutor versus Radovan Karadžić, The Prosecutor versus Ratko Mladić, and others. Executive summary The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina was the most violent of the conflicts which accompanied the break- up of Yugoslavia, and this paper explores international engagement with that war, including the process that led to the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement. Sarajevo and Srebrenica remain iconic symbols of international failure to prevent and end violent conflict, even in a small country in Europe. They are seen as monuments to the "humiliation" of Europe and the UN and the -

INDO 50 0 1106971426 29 60.Pdf (1.608Mb)

A m e r ic a n " L o w P o s t u r e " P o l ic y t o w a r d In d o n e s ia in t h e M o n t h s L e a d in g u p t o t h e 1965 "C o u p " 1 Frederick Bunnell Introduction This article seeks to contribute to the reconstruction, explanation, and evaluation of the Johnson Administration's response to President Sukarno's radicalization of Indonesia's do mestic politics and foreign policy in the first nine months of 1965 leading up to the abortive "coup" on October 1,1965. The focus throughout is on both the thinking and the politics of what can be termed "the 1965 Indonesia policy group."2 That unofficial group was the informal constellation of US officials both in Indonesia (in the Embassy-based country team)3 and in Washington (in the *This article has enjoyed a long, troubled odyssey. Growing out of intermittent research on American-Indonesian relations dating back to my doctoral dissertation field research in Jakarta in 1963-1965, the substance of the article, including its primary conclusions, was presented in papers at the August 1979 Indonesian Studies Con ference in Berkeley and the March 1980 International Studies Association Conference in Los Angeles. I am in debted to the American Philosophical Society, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation, and the Vassar College Faculty Research Committee for grants in 1976-1979 which facilitated the brunt of the archival and interview re search undergirding the article. -

The Art of War: the Protection of Cultural Property During the "Siege" of Sarajevo (1992-95)

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 14 Issue 1 Special Section: Art and War, 2004 Article 5 The Art of War: The Protection of Cultural Property during the "Siege" of Sarajevo (1992-95) Megan Kossiakoff Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Megan Kossiakoff, The Art of War: The Protection of Cultural Property during the "Siege" of Sarajevo (1992-95), 14 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 109 (2004) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol14/iss1/5 This Case Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kossiakoff: The Art of War: TheCOMMENT Protection of Cultural Property during the "S THE ART OF WAR: THE PROTECTION OF CULTURAL PROPERTY DURING THE "SIEGE" OF SARAJEVO (1992-95) I. INTRODUCTION Throughout the night of August 25, 1992, shells from Serb gunners fell on the National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo. The attack set off a blaze fueled by a collection representing hundreds of years of Bosnian history and culture. Librarians and community members, risking sniper fire, formed a human chain to move books to safety.' Despite emergency efforts, ninety percent of the collection was ash by daybreak.2 Unfortunately, this incident was not unique. The destruction of cultural artifacts during the "Siege" of Sarajevo was a loss not only to Bosnia,3 but also to the heritage of the world which now suffers a gap that cannot be closed. -

United Nations List of Delegations to the Second High-Level United

United Nations A/CONF.235/INF/2 Distr.: General 30 August 2019 Original: English Second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation Buenos Aires, 20–22 March 2019 List of delegations to the second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation 19-14881 (E) 110919 *1914881* A/CONF.235/INF/2 I. States ALBANIA H.E. Mr. Gent Cakaj, Acting Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs H.E. Ms. Besiana Kadare, Ambassador, Permanent Representative Mr. Dastid Koreshi, Chief of Staff of the Acting Foreign Minister ALGERIA H.E. Mr. Abdallah Baali, Ambassador Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Alternate Head of Delegation H.E. Mr. Benaouda Hamel, Ambassador of Algeria in Argentina, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina Representatives Mr. Nacim Gaouaoui, Deputy Director, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Zoubir Benarbia, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Algeria to the United Nations Mr. Mohamed Djalel Eddine Benabdoun, First Secretary, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina ANDORRA Mrs. Gemma Cano Berne, Director for Multilateral Affairs and Cooperation Mrs. Julia Stokes Sada, Desk Officer for International Cooperation for Development ANGOLA H.E. Mr. Manuel Nunes Junior, Minister of State for Social and Economic Development, Angola Representatives H.E. Mr. Domingos Custodio Vieira Lopes, Secretary of State for International Cooperation and Angolan Communities, Angola H.E. Ms. Maria de Jesus dos Reis Ferreira, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission of Angola to the United Nations ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA H.E. Mr. Walton Alfonso Webson, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission Representative Mr. Claxton Jessie Curtis Duberry, Third Secretary, Permanent Mission 2/42 19-14881 A/CONF.235/INF/2 ARGENTINA H.E. -

The Country Team and Local Staff Role | Excerpt from Inside a U.S. Embassy

PART II Foreign Service Work and Life: Embassy, Employee, Family By Shawn Dorman THE EMBASSY AND THE COUNTRY TEAM mbassies are located in the capital city of each country with which the United States has official relations, and serve as headquarters for U.S. gov - Eernment representation overseas. U.S. consulates are ancillary government offices in cities other than the capital. American and local employees serving in U.S. embassies and consulates work under the leadership of an ambassador to conduct diplomatic relations with the host country. The Department of State is the lead agency for conducting U.S. diplomacy and the ambassador, appointed by the U.S. president, reports to the Secretary of State. Diplomatic relations among nations, including diplomatic immunity and the inviolability of embassies, follow procedures framed by the 1961 Vienna Convention on the Conduct of Diplomatic Relations and Optional Protocols, ratified by the U.S. in 1969. The foreign affairs agencies that make up the Foreign Service—the Department of State, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Foreign Commercial Service, the Foreign Agricultural Service, and the International Broadcasting Bureau—are part of the overall U.S. mission in a country and usually have their offices inside the embassy. Each embassy can also be home to the offices of other U.S. government agencies and departments, in some countries as many as 40 dif - ferent entities. Agencies with a significant overseas presence include the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Drug Enforcement Agency, the Treasury Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Department of Homeland Security. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 2014

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION APRIL 2014 GREENING EMBASSIES CHIEf-Of-MISSION GUIDELINES HOW H.A. GILES LEARNED CHINESE FOREIGN April 2014 SERVICE Volume 91, No. 4 AFSA NEWS FOCUS GREENING EMBASSIES AFSA Releases Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 45 Eco-Diplomacy: Building the Foundation / 20 VP Voice State: Collaborating with Our Partner Organizations / 46 U.S. embassies and consulates around the world are becoming showcases VP Voice Retiree: Retirement for American leadership in best practices and sustainable technology. Begins Before Retirement / 47 BY DONNA M. MCINTIRE VP Voice FCS: The Budget Resource Merry-Go-Round / 48 The Greening Diplomacy Initiative: Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 49 Capturing Innovation / 24 AFSA Hosts Chiefs of Mission / 51 AFSA On the Hill: State’s homegrown Greening Diplomacy Initiative relies on seeding, Beyond Advocacy Day / 52 harvesting, sifting, implementing and sharing employees’ innovations New Association Management and ideas, large and small. System for AFSA / 53 BY CAROLINE D’ANGELO AFSA VP Meets with Florida Retirees / 54 The League of Green Embassies: 2013 Sinclaire Award Recipients / 54 AFSA Book Notes: American Leadership in Sustainability / 30 America’s First Globals / 55 A coalition of more than 100 U.S. embassies and consulates worldwide AFSA Partners with United Nations shares ideas and practical experience in the field. Association / 56 BY JOHN DAVID MOLESKY FSJ Editor-in-Chief Steps Down / 56 AFSA and DACOR Salute U.S. Marine Security Guards / 57 Finns Take the LEED in Green Embassy Design / 35 The Foreign Service Family: The Finnish embassy in Washington, D.C., is a green building that The Packout and Me / 59 was ahead of its time. -

Table of Contents

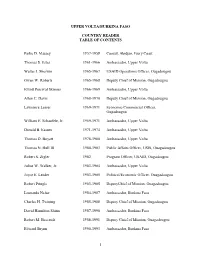

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Key Participants & Speakers

Republic of Tunisia MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Key Participants & Speakers – Biographies Hosts Mr. Beji Caïd Essebsi - President of the Republic - Tunisia Mr. Essebsi is the President of Tunisia since 2014. Previously, Mr. Essebsi held the position of Prime Minister for a brief period – March to October 2011. During his career, the President has held various high level positions, including Head of the Administration of National Security (1963), Minister of Interior from (1965-1969), Minister of Foreign Affairs (1981-1986) and President of the Chamber of Deputies (1990-1991). The President was also ambassador of Tunisia to West Germany and France. Mr. Youssef Chahed - Prime Minister - Tunisia Mr. Chahed was appointed Tunisian Prime Minister in August 2016. Before taking office, Mr. Chahed was Minister of Local Affairs in the previous government and previously held the position of Secretary of State for Fisheries. The Prime Minister is also an international expert in agriculture and agricultural policies for the United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the European Commission. Mr. Angel Gurría - Secretary-General - OECD Mr. Gurría is the OECD Secretary-General since 2006. The Secretary-General has held two ministerial posts in Mexico before joining the OECD - Minister of Foreign Affairs (1994-1998) and Minister of Finance and Public Credit (1998- 2000). Mr. Gurría chaired the International Task Force on Financing Water for All and is a member of several international initiatives, including the United Nations Secretary General Advisory Board, World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Water Security, International Advisory Board of Governors of the Centre for International Governance Innovation, among others.